Jean SIBELIUS (1865-1957)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

04 July 2020

04 July 2020 12:01 AM John Philip Sousa (1854-1932) Stars & Stripes forever – March Netherlands Radio Symphony Orchestra, Richard Dufallo (conductor) NLNOS 12:05 AM Thomas Demenga (1954-) Summer Breeze Andrea Kolle (flute), Maria Wildhaber (bassoon), Sarah Verrue (harp) CHSRF 12:13 AM Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Concerto in C major, RV.444 for recorder, strings & continuo Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni Antonini (recorder), Giovanni Antonini (director), Enrico Onofri (violin), Marco Bianchi (violin), Duilio Galfetti (violin), Paolo Beschi (cello), Paolo Rizzi (violone), Luca Pianca (theorbo), Gordon Murray (harpsichord), Duilio Galfetti (viola) DEWDR 12:23 AM Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) 3 Chansons for unaccompanied chorus BBC Singers, Alison Smart (soprano), Judith Harris (mezzo soprano), Daniel Auchincloss (tenor), Stephen Charlesworth (baritone), Stephen Cleobury (conductor) GBBBC 12:30 AM Bela Bartok (1881-1945) Out of Doors, Sz.81 David Kadouch (piano) PLPR 12:44 AM Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Rosamunde (Ballet Music No 2), D 797 Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Heinz Holliger (conductor) NONRK 12:52 AM John Cage (1912-1992) In a Landscape Fabian Ziegler (percussion) CHSRF 01:02 AM Jean-Francois Dandrieu (1682-1738) Rondeau 'L'Harmonieuse' from Pieces de Clavecin Book I Colin Tilney (harpsichord) CACBC 01:08 AM Bohuslav Martinu (1890-1959) The Frescoes of Piero della Francesca Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, Robert Stankovsky (conductor) SKSR 01:30 AM Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Metamorphosen for 23 solo strings (AV.142) Risor Festival Strings, -

Paul Weller with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Jules Buckley

For immediate release Paul Weller with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Jules Buckley concert date added to ‘Live from the Barbican’ line-up in spring 2021 Barbican Hall, Saturday 6 February 2021, 8pm The Barbican and Barbican Associate Orchestra, the BBC Symphony Orchestra are excited to announce that the orchestra and its Creative Artist in Association Jules Buckley, will be joined by legendary singer songwriter Paul Weller on Saturday 6 February for a concert reimagining Weller’s work in stunning orchestral settings as part of Live from the Barbican in 2021. In Weller’s first live performance for two years, songs spanning the broad spectrum of his career from The Jam to as yet unheard new material will delight fans and newcomers alike. Classic songs including ‘You Do Something to Me’, ‘English Rose’ and ‘Wild Wood’ along with tracks from Weller’s latest number 1 album ‘On Sunset’ will be heard as never before in brand new orchestral arrangements by Buckley. Weller, who takes cultural authenticity to the top of the charts, reunites with Steve Cradock for this one-off performance. Part of the acclaimed Live from the Barbican series which returns to the Centre in the spring, the concert will have a reduced, socially distanced live audience in the Barbican Hall, and it will also be available to watch globally via a livestream on the Barbican website. Whilst the concert will reflect on some of Weller’s back catalogue, as is typical of his constantly evolving career, it will look to the future with performances of songs from an album not released until May 2021, as well as welcoming guest artists to illustrate his work and the music that influenced him. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

The English Oboe: Rediscovered 4 AEGEUS (1996) 8’21 THOMAS ATTWOOD WALMISLEY (1814-1856) SONATINA NO

EDMUND RUBBRA (1901-1986) SONATA IN C FOR OBOE AND PIANO, OP. 100 1 Con moto 5’49 2 Elegy 4’15 3 Presto 3’30 EDWARD LONGSTAFF (1965- ) The English Oboe: Rediscovered 4 AEGEUS (1996) 8’21 THOMAS ATTWOOD WALMISLEY (1814-1856) SONATINA NO. 1 JAMES TURNBULL oboe 5 Andante mosso - Allegro moderato 8’49 JOHN CASKEN (1949- ) 6 AMETHYST DECEIVER FOR SOLO OBOE (2009) 7’16 (World premiere recording) GUSTAV HOLST (1874-1934) TERZETTO FOR FLUTE, OBOE AND VIOLA 7 Allegretto 6’59 8 Un poco vivace 4’36 MICHAEL BERKELEY (1948- ) THREE MOODS FOR UNACCOMPANIED OBOE 9 Very free. Moderato 5’24 10 Fairly free. Andante 2’33 11 Giocoso 2’13 RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958) SIX STUDIES IN ENGLISH FOLKSONG FOR COR ANGLAIS AND PIANO 12 Adagio 1’37 13 Andante sostenuto 1’28 14 Larghetto 1’31 15 Lento 1’36 16 Andante tranquillo 1’33 17 Allegro vivace 0’54 Total playing time: 68’34 James Turnbull ~ oboe / cor anglais (all tracks) Libby Burgess ~ piano (tracks 1-5 and 12-17) Matthew Featherstone ~ flute (tracks 7-8) Dan Shilladay ~ viola (tracks 7-8) FOREWORD PROGRAMME NOTES For a long time, I have been drawn towards English oboe music. It was therefore a Edmund Rubbra wrote much chamber music, including pieces for almost every straightforward decision to choose this repertoire to record. My aim was to introduce the instrument. He composed his Sonata for Oboe and Piano, op. 100, in 1958 for most varied programme possible: as a result, this disc spans over a century. -

CHAMBER Contents

CHAMBER Contents Page a1 3 a2 31 a3 53 a4 60 a5 80 a6+ 89 Supplementary Performances On Period Instruments 103 Classic & Historic Performances 114 a1 The symbol denotes a signpost navigating the user to related content elsewhere in the Edition. Keys are indicated thus: Symphony in C = C major · Sonata in c = C minor 2 CD 1 73.52 Nannerl Notenbuch (excerpts) 16 Minuet in C K15f 1.02 1 Andante in C (No.53) K1a 0.17 17 Fantasia (Prelude) in G K15g 0.59 2 Allegro in C (No.54) K1b 0.14 18 Contredanse in F K15h 1.00 3 Allegro in F (No.55) K1c 0.48 19 Minuet/Minore in A/a K15i/k 2.04 4 Minuet in F (No.56) K1d 1.14 20 Contredanse in A K15l 1.06 5 Minuet in G (No.62) K1e 21 Minuet in F K15m 1.11 Minuet in C (No.63) K1f 1.57 22 Andante in C K15n 2.34 6 Minuet in F (No.58) K2 0.54 23 Andante in D K15o 2.05 7 Allegro in B (No.59) K3 0.57 24 Movement for a Sonata in g K15p (Movement 1?) 3.05 8 Minuet in F b(No.49) K4 1.16 25 Andante in B K15q (Movement 2?) 3.18 9 Minuet in F (No.61) K5 1.06 26 Andante in g bK15r (Movement 3?) 1.31 10 Allegro in C (No.20) K9a 3.10 27 Rondo in C K15s 0.37 Erik Smith harpsichord 28 Movement for a Sonata in F K15t 2.18 CD 10: alternative versions from Nannerl Notenbuch 29 Sicilianos in c K15u 1.45 CD 174: K9b fragment · CD 177: K9b completion 30 Movement for a Sonata in F K15v 2.30 31 Allemande in B K15w 2.18 London Sketchbook b Chamber a1 32 Movement for a Sonata in F K15x 0.54 11 Allegretto in F K15a 1.38 33 Minuet in G K15y 0.54 12 Andantino in C K15b 1.03 34 Gigue in c K15z 2.08 CD 194: K15b first version 35 Movement -

Winter Concerts

WINTER CONCERTS PLANNING THE LONDON SEASON Plans for the new 1954-55 season are now taking shape, and Londoners are pro mised an intensive winter’s music-making. The Royal Philharmonic Society’s series of eight orchestral concerts will open at the Festival Hall on October 20 with a French programme conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham. In all of the eight concerts there is a happy balance between familiar and unfamiliar music, and, besides Sir Thomas, the orchestra will have among its conductors Sir Malcolm Sar gent. Sir Arthur Bliss, Mr. Hans Schmidt- Isserstedt, Mr. Paul Hindemith, Mr. Otto Klemperer, and Mr. Rudolf Schwarz. The first performance of Rubbra's sixth symphony is promised for November 17, a programme de voted to the music of Sir Arthur Bliss for January 26, and Hindemith's symphony, “ Die Harmonie der Welt ” for March 16. The Royal Choral Society's programmes are keeping to familiar lines, with Vaughan Williams's Dona Nobis Pacetn and “ A Sea Symphony ” on November 27 as the only con temporary works in the series. The perform ance of Messiah under Sir Malcolm Sargent on January 8 will be the society's hundredth concert since its formation in 1871. Mr. Wilfrid Van Wyck will be responsible for the visits of many international celebrities to London between October and May, with Mr. Robert Bronstein, Mr. Massino Freccia, Mr. Karl Krueger, Mr. Alberto Bolet, Mr. Galbera, Mr. Eugen Szenkar, Mr. George Barati, and Mr. Royalton Kisch among the conductors, and Miss Livia Rev, Mr. Rudolf Firkusny, Mr. Byron Janis, Miss Jeanne Demessieux, Mr. -

JOAN SUTHERLAND John Pritchard (1918–89)

JOAN SUTHERLAND John Pritchard (1918–89). Walthamstow-born, John Pritchard learned his craft as principal conductor of the Derby String Orchestra, before joining the music staff of Glyndebourne in 1947. Appointed Chorus Master in 1949, he was soon sharing major Mozart productions with Fritz Busch, conducting the London Philharmonic Orchestra there and swiftly expanding his repertoire. The company’s Musical Director from 1969 to 1977, he was also a regular guest at the Royal Opera, where in 1955 he conducted the premiere of Tippett’s A Midsummer Marriage. His opera and concert work encircled the globe, with periods at the helm of many companies and orchestras, notably the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and BBC Symphony. He was knighted in 1983. Though his full diary could result in perfunctory routine, fiery theatricality and a grasp of essentials inform his best work – not least in many studio and off-air recordings made with his ‘home’, Glyndebourne company, and for BBC radio. Joan Sutherland (1926–2010). The world-renowned soprano Joan Sutherland left her Sydney home for London in 1952, with the ultimate aim of singing Wagner. Contracted to Covent Garden, she felt her future lay in heavy, dramatic roles; and her early assignments there included Amelia in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera and the title role in Aida. Soon her breathtaking agility, crystalline staccatos and unique stratospheric purity became evident – not least as Jenifer in Tippett’s The Midsummer Marriage, followed swiftly by the doll Olympia in Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann (both 1955). Although increasingly identified with the bel canto repertoire, until her 1959 Covent Garden triumph in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor she kept her options open. -

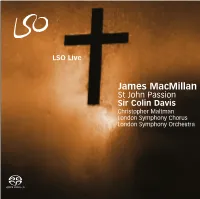

James Macmillan

LSO Live LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk James MacMillan LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les St John Passion plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant Sir Colin Davis ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Christopher Maltman circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres London Symphony Chorus du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns herein: lso.co.uk LSO0671 James MacMillan St John Passion (The Passion of Our Lord Disc 1 – Part I Total 54’14” Jesus Christ According to St John) 1 i. The arrest of Jesus 10’17” p12 Sir Colin Davis London Symphony Orchestra 2 ii. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

The Music of Edmund Rubbra, by Ralph Scott Grover (Review)

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Music Theory, History & Composition College of Visual & Performing Arts 9-1994 The uM sic of Edmund Rubbra, by Ralph Scott Grover (review) Julian Onderdonk West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/musichtc_facpub Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Onderdonk, J. (1994). The usicM of Edmund Rubbra, by Ralph Scott Grover (review). Notes, Second Series, 51(1), 152-153. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/musichtc_facpub/40 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Visual & Performing Arts at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Theory, History & Composition by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 152 NOTES, September 1994 A hot tip: The Sorabji Archive, now five bra's working methods and of its evolution years old or so, is the only source for those over his career. He also makes frequent use wishing to acquire photocopies of the music of the Rubbra literature, printing sizable and the composer's writings, whether pub- portions not only of performance and lished or not. The address is: Easton Dene, record reviews, but of scholarly essays as Bailbrook Lane, Bath BA1 7AA, England. well. MARC-ANDR]HAMELIN The pity is that this excellently thorough Philadelphia book displays on nearly every page a de- fensive awareness of Rubbra's secondary stature. Like so many other studies of "mi- The Music of Edmund Rubbra. -

Download the Concert Programme (PDF)

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Thursday 18 May 2017 7.30pm Barbican Hall Vaughan Williams Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus Brahms Double Concerto INTERVAL Holst The Planets – Suite Sir Mark Elder conductor Roman Simovic violin Tim Hugh cello Ladies of the London Symphony Chorus London’s Symphony Orchestra Simon Halsey chorus director Concert finishes approx 9.45pm Supported by Baker McKenzie 2 Welcome 18 May 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief Welcome to tonight’s LSO concert at the Barbican. BMW LSO OPEN AIR CLASSICS 2017 This evening we are joined by Sir Mark Elder for the second of two concerts this season, as he conducts The London Symphony Orchestra, in partnership with a programme of Vaughan Williams, Brahms and Holst. BMW and conducted by Valery Gergiev, performs an all-Rachmaninov programme in London’s Trafalgar It is always a great pleasure to see the musicians Square this Sunday 21 May, the sixth concert in of the LSO appear as soloists with the Orchestra. the Orchestra’s annual BMW LSO Open Air Classics Tonight, after Vaughan Williams’ Five Variants of series, free and open to all. Dives and Lazarus, the LSO’s Leader Roman Simovic and Principal Cello Tim Hugh take centre stage for lso.co.uk/openair Brahms’ Double Concerto. We conclude the concert with Holst’s much-loved LSO WIND ENSEMBLE ON LSO LIVE The Planets, for which we welcome the London Symphony Chorus and Choral Director Simon Halsey. The new recording of Mozart’s Serenade No 10 The LSO premiered the complete suite of The Planets for Wind Instruments (‘Gran Partita’) by the LSO Wind in 1920, and we are thrilled that the 2002 recording Ensemble is now available on LSO Live. -

Musicweb International August 2020 RETROSPECTIVE SUMMER 2020

RETROSPECTIVE SUMMER 2020 By Brian Wilson The decision to axe the ‘Second Thoughts and Short Reviews’ feature left me with a vast array of part- written reviews, left unfinished after a colleague had got their thoughts online first, with not enough hours in the day to recast a full review in each case. This is an attempt to catch up. Even if in almost every case I find myself largely in agreement with the original review, a brief reminder of something you may have missed, with a slightly different slant, may be useful – and, occasionally, I may be raising a dissenting voice. Index [with page numbers] Malcolm ARNOLD Concerto for Organ and Orchestra – see Arthur BUTTERWORTH Johann Sebastian BACH Concertos for Harpsichord and Strings – Volume 1_BIS [2] Johann Sebastian BACH, Georg Philipp TELEMANN, Carl Philipp Emanuel BACH The Father, the Son and the Godfather_BIS [2] Sir Arnold BAX Morning Song ‘Maytime in Sussex’ – see RUBBRA Amy BEACH Piano Quintet (with ELGAR Piano Quintet)_Hyperion [9] Sir Arthur BLISS Piano Concerto in B-flat – see RUBBRA Benjamin BRITTEN Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, etc._Alto_Regis [15, 16] Arthur BUTTERWORTH Symphony No.1 (with Ruth GIPPS Symphony No.2, Malcolm ARNOLD Concerto for Organ and Orchestra)_Musical Concepts [16] Paul CORFIELD GODFREY Beren and Lúthien: Epic Scenes from the Silmarillion - Part Two_Prima Facie [17] Sir Edward ELGAR Symphony No.2_Decca [7] - Sea Pictures; Falstaff_Decca [6] - Falstaff; Cockaigne_Sony [7] - Sea Pictures; Alassio_Sony [7] - Violin Sonata (with Ralph VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Violin Sonata; The Lark Ascending)_Chandos [9] - Piano Quintet – see Amy BEACH Gerald FINZI Concerto for Clarinet and Strings – see VAUGHAN WILLIAMS [10] Ruth GIPPS Symphony No.2 – see Arthur BUTTERWORTH Alan GRAY Magnificat and Nunc dimittis in f minor – see STANFORD Modest MUSSORGSKY Pictures from an Exhibition (orch.