AJLS 4,1 F5 51-84.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aryeh Neier Interview

Interview Dr. Daniel Stahl Quellen zur Geschichte der Menschenrechte Aryeh Neier Aryeh Neier, born in 1937, was active in the U.S. civil rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1978 he turned to the issue of international human rights and was among the founders of Helsinki Watch, which was renamed Human Rights Watch in 1988. After his work for HRW he played a principal role in building the Open Society Foundations, which since the 1990s has supported projects related to issues of human rights. Interview The following interview with Prof. Dr. Aryeh Neier was conducted in his office at the Open Society Foundations by Prof. Dr. Claus Kreß, Director of the Institute for International Peace and Security Law of the University of Cologne, and Dr. Daniel Stahl, coordinator of the Study Group »Human Rights in the 20th Century«, on the afternoon of March 3, 2015. By advance agreement the discussion was limited to two hours and there was no opportunity for a spontaneous extension. Neier spoke in a deliberate manner and required little time to recall the situations and facts he describes. Daniel Stahl I would like to start with your time in England, where you went after leaving Germany in 1939. How did you as a child experience this time – the World War, and the persecution of Jews? Aryeh Neier In general, I had a fairly happy childhood. There is one exception to that. During the first year that I was in England, when I was still a very young child, I was in a hostel for refugee children. -

The Aclu: Evangelists, Nazis and Bakke

Earl Raab September 12, 1977 THE ACLU: EVANGELISTS, NAZIS AND BAKKE The American Civil Liberties Union is one of these organizations that would have to be created if it didn't already exist. Its single-minded purpose is to protect those First Amendment rights which distinguish a democratic society from a Nazi or Soviet Society. In pursuit of that purpose, the ACLU gets into many issues - and doesn't necessarily end up on the right side of every tangle. The Northern California Chapter of the ACLU has been most recently of great assistance to the Jewish community on the issue of Christian evangelism in the high schools. Last year the evangelizers began to swarm onto high school grounds. The Jewish community objected; and the ACLU followed with a strong legal letter to every school administrator in this area. The ACLU has also supported the Jewish community on related legislative issues in Sacramento. But nationally, the ACLU is in the middle of one of its most controversial cases: it is defending the right of the Nazis to meet in Skokie, Illinois. This is a standard position for the ACLU: 11 I:f everyone doesn't have the right to speak, no one will have that right. 11 Aryeh Neier, a refugee from Nazi Germany and national esecutive director of the ACLU, puts it this"way: "One comment that often appears in letters I receive is that, if the Nazis come to power, the ACLU and its leaders would not be allowed to survive. Of course that is true. Civil liberties is the antithesis of Nazism. -

REPORT Donations Are Fully Tax-Deductible

SUPPORT THE NYCLU JOIN AND BECOME A CARD-CARRYING MEMBER Basic individual membership is only $20 per year, joint membership NEW YORK is $35. NYCLU membership automatically extends to the national CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION American Civil Liberties Union and to your local chapter. Membership is not tax-deductible and supports our legal, legislative, lobbying, educational and community organizing efforts. ANNUAL MAKE A TAX-DEDUCTIBLE GIFT Because the NYCLU Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, REPORT donations are fully tax-deductible. The NYCLU Foundation supports litigation, advocacy and public education but does not fund legislative lobbying, which cannot be supported by tax-deductible funds. BECOME AN NYCLU ACTIVIST 2013 NYCLU activists organize coalitions, lobby elected officials, protest civil liberties violations and participate in web-based action campaigns THE DESILVER SOCIETY Named for Albert DeSilver, one of the founders of the ACLU, the DeSilver Society supports the organization through bequests, retirement plans, beneficiary designations or other legacy gifts. This special group of supporters helps secure civil liberties for future generations. THE AMICUS CLUB Lawyers and legal professionals are invited to join our Amicus Club with a donation equal to the value of one to four billable hours. Club events offer members the opportunity to network, stay informed of legal developments in the field of civil liberties and earn CLE credits. THE EASTMAN SOCIETY Named for the ACLU’s co-founder, Crystal Eastman, the Eastman Society honors and recognizes those patrons who make an annual gift of $5,000 or more. Society members receive a variety of benefits. Go to www.nyclu.org to sign up and stand up for civil liberties. -

The Man Who Shaped History Nyreview of Books, Michael Ignatieff, October 11, 2012

The Man Who Shaped History NYReview of Books, Michael Ignatieff, October 11, 2012 The International Human Rights Movement: A History by Aryeh Neier Princeton University Press, 379 pp., $35.00 Aryeh Neier giving a talk about the international human rights movement at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, February 2012 When the blind human rights activist and lawyer Chen Guangcheng arrived from Beijing to begin a new life at New York University in mid-May, with the camera flashes ricocheting off his dark glasses, his first moments in freedom recalled the euphoric day in 1986 when the diminutive Anatoly Shcharansky crossed the Glienecke Bridge from East to West Berlin with an impish grin on his face. In both cases, a single person demonstrated the asymmetric power that humbles powerful regimes. When Shcharansky—a dissident who had spent nine years in the Gulag—won his freedom, he and those who had gone before—Andrei Sakharov and Alexander Solzhenitsyn—helped to weaken tyranny and set it on the downward slope to its eventual collapse. The question today is whether human rights activists still possess the power to drain legitimacy away from repressive regimes. Then and now the United States had no desire to upset its relations with a powerful rival just for the sake of human rights, and yet, in the 1980s, human rights demands in Eastern Europe began wearing away the façade and inner confidence of Soviet rule. China now is what the Soviet system was to the human rights movement in the cold war: its largest strategic challenge, the one regime with global reach that believes it can deny full civil and political rights in perpetuity and permanently deny its citizens access to the Internet and the information revolution. -

Icc-01/18-73 16-03-2020 1/30 Ek Pt

ICC-01/18-73 16-03-2020 1/30 EK PT Original: English No.: ICC-01/18 Date: 16 March 2020 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Péter Kovács, Presiding Judge Judge Marc Perrin de Brichambaut Judge Reine Adélaïde Sophie Alapini-Gansou SITUATION IN THE STATE OF PALESTINE Public Submissions Pursuant to Rule 103 Source: Professors Asem Khalil & Halla Shoaibi No. ICC-01/18 1/30 16 March 2020 ICC-01/18-73 16-03-2020 2/30 EK PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Ms. Fatou Bensouda, Prosecutor Mr James Stewart, Deputy Prosecutor Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence Ms. Paolina Massidda States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Counsel Support Section Mr Peter Lewis, Registrar Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section Mr. Philipp Ambach, Chief No. ICC-01/18 2/30 16 March 2020 ICC-01/18-73 16-03-2020 3/30 EK PT Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 4 II. SUBMISSIONS..................................................................................................................... 4 A. The absence of enforcement jurisdiction does not negate prescriptive jurisdiction. ............................................................................................................................. -

Law Reports of Trial of War Criminals, Volume VI, English Edition

LAW REPORTS OF TRIALS OF WAR CRIMINALS Selected and prepared by THE UNITED NATIONS WAR CRIMES COMMISSION VOLUME VI LONDON PUBLISHED FOR THE UNITED NATIONS WAR CRIMES COMMISSION BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 194 8 Price 5S. cd. net Official Publications on THE TRIAL OF GERMAN MAJOR WAR CRIMINALS AT NUREMBERG JUDGMENT Judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Trial of German Major War Criminals: September 30 and October 1, 1946 (Cmd. 6964) 2s. 6d. (2s. 8d.) SPEECHES Opening speeches of the Chief Prosecutors 2s. 6d. (2s. 9d.) Speeches of the Chief Prosecutors at the Close of the Case against the Individual Defendants 3s. (38. 4d.) Speeches of the Prosecutors at the Close of the Case against the Indicted Organisations 2s. 6d. (2s. 9d.) PRICES IN BRACKETS INCLUDE POSTAGE CONTINUED ON PAGE iii OF COVER LAW REPORTS OF TRIALS OF WAR CRIMINALS Selected and prepared by THE UNITED NATIONS WAR CRIMES COMMISSION Volume VI , .... ,.s.~.' PROPERTY OF U. S. ARMY -}; THE JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL'S ?CI::!OO~ .~~~ LIBRARY___ ..... _,I _ ...... ,~.~~-~~~.. LONDON: PUBLISHED FOR THE UNITED NATIONS WAR CRIMES COMMISSION BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 1948 CONTENTS PAGE FOREWORD BY THE RT. HON. THE LORD WRIGHT OF DURLEY . .. V THE CASES: 35. TRIAL -OF JOSEF ALTSTOTTER AND OT!lERS United States Military Tribunal, Nuremberg, 17th February-4th December, 1947 I HEADING NOTES AND SUMMARY 1 A. OUTLINE OF THE PROCEEDINGS 2 1. THE COURT 2 2. THE CHARGES 2 3. A CHALLENGE TO THE SUFFICIENCY OF COUNT ONE OF THE INDICTMENT .. 5 4. THE EVIDENCE BEFORE THE TRIBUNAL . -

The Contributions of State Responsibility for Genocide to Transitional Justice

A NEGLECTED OPTION: THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF STATE RESPONSIBILITY FOR GENOCIDE TO TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE SAIRA MOHAMED* Despite the pervasive involvement of government bureaucra- cies in perpetratinggenocide and other atrocities, the inter- national community's efforts to assist societies emerging from these horrors have relied primarily on establishing the guilt of individuals in criminal tribunals, rather than ad- dressing the wrongs committed by governments through other means. The International Court of Justice diverged from this approach to transitionaljustice when it decided in 2007 that states themselves can be held civilly responsible for committing genocide. Characterizing the decision as re- viving the concept of collective guilt in contravention of ac- cepted principles of transitionaljustice, some warned that holding states responsible for mass atrocity would trigger renewed conflict and prevent peace in societies attempting to recover from violent conflict or mass atrocity. This Article challenges the notion that state responsibility for genocide is incompatible with transitionaljustice. The jurisprudence of internationalcriminal tribunals reveals that despite the tri- bunals' mandate to determine the guilt only of individuals, group dynamics play a significant underlying role in prose- cutions and convictions. Moreover, holding states responsi- ble for committing genocide contributes to accountability and truth-telling, the professed goals of transitionaljustice, while criminal trials come up short. When atrocities are committed through the systematic, coordinated actions of a state, contemplating accountabilityonly in relation to the of- fenses of individuals is imprecise and incomplete. In order to establish meaningful accountability and reveal the truth about a genocide, the state institutions that urged, organ- * James Milligan Fellow, Columbia Law School. The author formerly served as a senior advisor to the Special Envoy for Sudan in the U.S. -

Aryeh Neier Laudatio

Aryeh Neier Laudatio Aryeh Neier is one of the world’s leading advocates for open society. Founder of two great international human rights organizations, and one-time director of the leading civil liberties organization in the US, Aryeh has been at the center of the global rights movement for more than half a century. He has led campaigns for freedom of expression, criminal justice reform, racial and gender equality, personal privacy, international justice and accountability for crimes against humanity and genocide. To do so, he has developed unparalleled expertise, encyclopedic knowledge and an uncanny ability to marshal arguments and people to advance the cause of human rights. Born in Nazi Germany, Aryeh and his family escaped to England on the eve of World War II. As an American university student, he was inspired by the 1956 Hungarian revolution to start a campus forum on freedom and justice. In 1963, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Aryeh joined the staff of the American Civil Liberties Union, where he participated in the struggle for racial desegregation in America. In 1970, he was chosen to direct the ACLU, and he led it through intense controversies over freedoms of speech and assembly during the Vietnam War. Later, he mobilized to defend civil liberties against massive abuses by the Nixon Administration. In 1974, President Nixon was held responsible for these crimes, impeached in the US House of Representatives and forced to resign from office in 1974. But even the impeachment of a president was less controversial than Aryeh’s courageous defense of the freedoms of those with whom he most intensely disagreed – a small band of Neo-Nazis who sought to march through the heavily Jewish town of Skokie, Illinois, where there were many Holocaust survivors. -

Civil Liberties in Uncivil Times: the Ep Rilous Quest to Preserve American Freedoms Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2007 Civil Liberties in Uncivil Times: The eP rilous Quest to Preserve American Freedoms Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Civil Liberties in Uncivil Times: The eP rilous Quest to Preserve American Freedoms, 2 London Law Review 2 (2007) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. bepress Legal Series Year Paper Civil Liberties in Uncivil Times: The Perilous Quest to Preserve American Freedoms Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore This working paper is hosted by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress) and may not be commercially reproduced without the permission of the copyright holder. http://law.bepress.com/expresso/eps/1090 Copyright c 2006 by the author. Civil Liberties in Uncivil Times: The Perilous Quest to Preserve American Freedoms Abstract The perilous quest to preserve civil liberties in uncivil times is not an easy one, but the wisdom of Benjamin Franklin should remain a beacon: “Societies that trade liberty for security end often with neither.” Part I of this article is a brief history of civil liberties in America during past conflicts. -

No. ICC-01/04-02/06 23 February 2017 Original

ICC-01/04-02/06-1798 23-02-2017 1/38 NM T OA5 Original: English No.: ICC-01/04-02/06 Date: 23 February 2017 THE APPEALS CHAMBER Before: Judge Sanji Mmasenono Monageng, Presiding Judge Judge Christine Van den Wyngaert Judge Howard Morrison Judge Piotr Hofmański Judge Raul C. Pangalangan SITUATION IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO IN THE CASE OF THE PROSECUTOR v. BOSCO NTAGANDA Public Former Child Soldiers’ observations on the “Appeal from the Second decision on the Defence’s challenge to the jurisdiction of the Court in respect of Counts 6 and 9” Source: Office of Public Counsel for Victims (CLR1) No. ICC-01/04-02/06 1/38 23 February 2017 ICC-01/04-02/06-1798 23-02-2017 2/38 NM T OA5 Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Ms Fatou Bensouda Mr Stéphane Bourgon Mr James Stewart Mr Chris Gosnell Ms Helen Brady Ms Nicole Samson Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Ms Sarah Pellet Mr Mohamed Abdou Mr Dmytro Suprun Ms Anne Grabowski Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Counsel Support Section Mr Herman von Hebel Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section No. ICC-01/04-02/06 2/38 23 February 2017 ICC-01/04-02/06-1798 23-02-2017 3/38 NM T OA5 I. -

The Legal Limits of Universal Jurisdiction

The Legal Limits of Universal Jurisdiction ANTHONY J. COLANGELO* I. Introduction ............................................................................... 150 II. Universal Jurisdiction's Prescriptive-Adjudicative Symbiosis . 157 III. The Customary Law of Universal Jurisdiction .......................... 163 A. Adjudicative Versus Prescriptive Universal Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 163 B. "Conventional" Versus Customary Universal Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 166 C. Treaties and the Prescriptive Substance of Universal C rim es .............................................................................. 169 IV. Evolving and Enforcing the Limits of Universal Jurisdiction ... 182 V . C onclusion ................................................................................. 185 V I. A ppendix ................................................................................... 186 Despite all the attention it receives from both its supporters and crit- ics, universal jurisdiction remains one of the more confused doctrines of international law. Indeed, while commentary has focused largely and unevenly on policy and normative arguments either favoring or under- cutting the desirability of its exercise, a straightforward legal analysis breaking down critical aspects of this extraordinary form of jurisdiction remains conspicuously missing. Yet universal jurisdiction's increased practice by states calls out for such a clear descriptive -

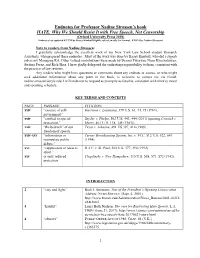

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen's Book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen’s book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship (Oxford University Press 2018) Endnotes last updated 4/27/18 by Kasey Kimball (lightly edited, mostly for format, 4/28/18 by Nadine Strossen) Note to readers from Nadine Strossen: I gratefully acknowledge the excellent work of my New York Law School student Research Assistants, who prepared these endnotes. Most of the work was done by Kasey Kimball, who did a superb job as my Managing RA. Other valued contributions were made by Dennis Futoryan, Nana Khachaturyan, Stefano Perez, and Rick Shea. I have gladly delegated the endnoting responsibility to them, consistent with the practice of law reviews. Any readers who might have questions or comments about any endnote or source, or who might seek additional information about any point in the book, is welcome to contact me via Email: [email protected]. I will endeavor to respond as promptly as feasible, consistent with a heavy travel and speaking schedule. KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS PAGE PASSAGE CITATION xxiv “essence of self- Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64, 74, 75 (1964). government.” xxiv “entitled to special Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 444 (2011) (quoting Connick v. protection.” Myers, 461 U. S. 138, 145 (1983)). xxiv “the bedrock” of our Texas v. Johnson, 491 US 397, 414 (1989). freedom of speech. xxiv-xxv “information or Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. FCC, 512 U.S. 622, 641 manipulate public (1994). debate.” xxv “suppression of ideas is R.A.V. v. St.