The Decision to Enter Mitosis: Feedback and Redundancy in the Mitotic Entry Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cryoelectron Microscopy Structure of the Human CDK-Activating Kinase

The cryoelectron microscopy structure of the human CDK-activating kinase Basil J. Grebera,b,1,2, Juan M. Perez-Bertoldic, Kif Limd, Anthony T. Iavaronee, Daniel B. Tosoa, and Eva Nogalesa,b,d,f,2 aCalifornia Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3), University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; bMolecular Biophysics and Integrative Bio-Imaging Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720; cBiophysics Graduate Group, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; dDepartment of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; eQB3/Chemistry Mass Spectrometry Facility, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; and fHoward Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 Edited by Seth A. Darst, Rockefeller University, New York, NY, and approved August 4, 2020 (received for review May 14, 2020) The human CDK-activating kinase (CAK), a complex composed of phosphoryl transfer (11). However, in addition to cyclin binding, cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 7, cyclin H, and MAT1, is a critical full activation of cell cycle CDKs requires phosphorylation of the regulator of transcription initiation and the cell cycle. It acts by T-loop (9, 12). In animal cells, these activating phosphorylations phosphorylating the C-terminal heptapeptide repeat domain of are carried out by CDK7 (13, 14), itself a cyclin-dependent ki- the RNA polymerase II (Pol II) subunit RPB1, which is an important nase whose activity depends on cyclin H (14). regulatory event in transcription initiation by Pol II, and it phos- In human and other metazoan cells, regulation of transcription phorylates the regulatory T-loop of CDKs that control cell cycle initiation by phosphorylation of the Pol II-CTD and phosphor- progression. -

Mitosis Vs. Meiosis

Mitosis vs. Meiosis In order for organisms to continue growing and/or replace cells that are dead or beyond repair, cells must replicate, or make identical copies of themselves. In order to do this and maintain the proper number of chromosomes, the cells of eukaryotes must undergo mitosis to divide up their DNA. The dividing of the DNA ensures that both the “old” cell (parent cell) and the “new” cells (daughter cells) have the same genetic makeup and both will be diploid, or containing the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell. For reproduction of an organism to occur, the original parent cell will undergo Meiosis to create 4 new daughter cells with a slightly different genetic makeup in order to ensure genetic diversity when fertilization occurs. The four daughter cells will be haploid, or containing half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. The difference between the two processes is that mitosis occurs in non-reproductive cells, or somatic cells, and meiosis occurs in the cells that participate in sexual reproduction, or germ cells. The Somatic Cell Cycle (Mitosis) The somatic cell cycle consists of 3 phases: interphase, m phase, and cytokinesis. 1. Interphase: Interphase is considered the non-dividing phase of the cell cycle. It is not a part of the actual process of mitosis, but it readies the cell for mitosis. It is made up of 3 sub-phases: • G1 Phase: In G1, the cell is growing. In most organisms, the majority of the cell’s life span is spent in G1. • S Phase: In each human somatic cell, there are 23 pairs of chromosomes; one chromosome comes from the mother and one comes from the father. -

Role of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 1 in Translational Regulation in the M-Phase

cells Review Role of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 1 in Translational Regulation in the M-Phase Jaroslav Kalous *, Denisa Jansová and Andrej Šušor Institute of Animal Physiology and Genetics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Rumburska 89, 27721 Libechov, Czech Republic; [email protected] (D.J.); [email protected] (A.Š.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 April 2020; Accepted: 24 June 2020; Published: 27 June 2020 Abstract: Cyclin dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) has been primarily identified as a key cell cycle regulator in both mitosis and meiosis. Recently, an extramitotic function of CDK1 emerged when evidence was found that CDK1 is involved in many cellular events that are essential for cell proliferation and survival. In this review we summarize the involvement of CDK1 in the initiation and elongation steps of protein synthesis in the cell. During its activation, CDK1 influences the initiation of protein synthesis, promotes the activity of specific translational initiation factors and affects the functioning of a subset of elongation factors. Our review provides insights into gene expression regulation during the transcriptionally silent M-phase and describes quantitative and qualitative translational changes based on the extramitotic role of the cell cycle master regulator CDK1 to optimize temporal synthesis of proteins to sustain the division-related processes: mitosis and cytokinesis. Keywords: CDK1; 4E-BP1; mTOR; mRNA; translation; M-phase 1. Introduction 1.1. Cyclin Dependent Kinase 1 (CDK1) Is a Subunit of the M Phase-Promoting Factor (MPF) CDK1, a serine/threonine kinase, is a catalytic subunit of the M phase-promoting factor (MPF) complex which is essential for cell cycle control during the G1-S and G2-M phase transitions of eukaryotic cells. -

Targeting Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 9 and Myeloid Cell Leukaemia 1 in MYC-Driven B-Cell Lymphoma

Targeting cyclin-dependent kinase 9 and myeloid cell leukaemia 1 in MYC-driven B-cell lymphoma Gareth Peter Gregory ORCID ID: 0000-0002-4170-0682 Thesis for Doctor of Philosophy September 2016 Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology The University of Melbourne Doctor of Philosophy Submitted in total fulfilment of the degree of Abstract Aggressive B-cell lymphomas include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma and intermediate forms. Despite high response rates to conventional immuno-chemotherapeutic approaches, an unmet need for novel therapeutic by resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The proto-oncogene MYC is strategies is required in the setting of relapsed and refractory disease, typified frequently dysregulated in the aggressive B-cell lymphomas, however, it has proven an elusive direct therapeutic target. MYC-dysregulated disease maintains a ‘transcriptionally-addicted’ state, whereby perturbation of A significant body of evidence is accumulating to suggest that RNA polymerase II activity may indirectly antagonise MYC activity. Furthermore, very recent studies implicate anti-apoptotic myeloid cell leukaemia 1 (MCL-1) as a critical survival determinant of MYC-driven lymphoma. This thesis utilises pharmacologic and genetic techniques in MYC-driven models of aggressive B-cell lymphoma to demonstrate that cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) and MCL-1 are oncogenic dependencies of this subset of disease. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, dinaciclib, and more selective CDK9 inhibitors downregulation of MCL1 are used -

List, Describe, Diagram, and Identify the Stages of Meiosis

Meiosis and Sexual Life Cycles Objective # 1 In this topic we will examine a second type of cell division used by eukaryotic List, describe, diagram, and cells: meiosis. identify the stages of meiosis. In addition, we will see how the 2 types of eukaryotic cell division, mitosis and meiosis, are involved in transmitting genetic information from one generation to the next during eukaryotic life cycles. 1 2 Objective 1 Objective 1 Overview of meiosis in a cell where 2N = 6 Only diploid cells can divide by meiosis. We will examine the stages of meiosis in DNA duplication a diploid cell where 2N = 6 during interphase Meiosis involves 2 consecutive cell divisions. Since the DNA is duplicated Meiosis II only prior to the first division, the final result is 4 haploid cells: Meiosis I 3 After meiosis I the cells are haploid. 4 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ Chromosomes condense. Because of replication during interphase, each chromosome consists of 2 sister chromatids joined by a centromere. ¾ Synapsis – the 2 members of each homologous pair of chromosomes line up side-by-side to form a tetrad consisting of 4 chromatids: 5 6 1 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ During synapsis, sometimes there is an exchange of homologous parts between non-sister chromatids. This exchange is called crossing over. 7 8 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis (2N=6) Prophase I: ¾ the spindle apparatus begins to form. ¾ the nuclear membrane breaks down: Prophase I 9 10 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, 4 Possible Metaphase I Arrangements: Metaphase I: ¾ chromosomes line up along the equatorial plate in pairs, i.e. -

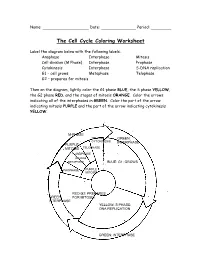

The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet

Name: Date: Period: The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet Label the diagram below with the following labels: Anaphase Interphase Mitosis Cell division (M Phase) Interphase Prophase Cytokinesis Interphase S-DNA replication G1 – cell grows Metaphase Telophase G2 – prepares for mitosis Then on the diagram, lightly color the G1 phase BLUE, the S phase YELLOW, the G2 phase RED, and the stages of mitosis ORANGE. Color the arrows indicating all of the interphases in GREEN. Color the part of the arrow indicating mitosis PURPLE and the part of the arrow indicating cytokinesis YELLOW. M-PHASE YELLOW: GREEN: CYTOKINESIS INTERPHASE PURPLE: TELOPHASE MITOSIS ANAPHASE ORANGE METAPHASE BLUE: G1: GROWS PROPHASE PURPLE MITOSIS RED:G2: PREPARES GREEN: FOR MITOSIS INTERPHASE YELLOW: S PHASE: DNA REPLICATION GREEN: INTERPHASE Use the diagram and your notes to answer the following questions. 1. What is a series of events that cells go through as they grow and divide? CELL CYCLE 2. What is the longest stage of the cell cycle called? INTERPHASE 3. During what stage does the G1, S, and G2 phases happen? INTERPHASE 4. During what phase of the cell cycle does mitosis and cytokinesis occur? M-PHASE 5. During what phase of the cell cycle does cell division occur? MITOSIS 6. During what phase of the cell cycle is DNA replicated? S-PHASE 7. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell grow? G1,G2 8. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell prepare for mitosis? G2 9. How many stages are there in mitosis? 4 10. Put the following stages of mitosis in order: anaphase, prophase, metaphase, and telophase. -

Cell Life Cycle and Reproduction the Cell Cycle (Cell-Division Cycle), Is a Series of Events That Take Place in a Cell Leading to Its Division and Duplication

Cell Life Cycle and Reproduction The cell cycle (cell-division cycle), is a series of events that take place in a cell leading to its division and duplication. The main phases of the cell cycle are interphase, nuclear division, and cytokinesis. Cell division produces two daughter cells. In cells without a nucleus (prokaryotic), the cell cycle occurs via binary fission. Interphase Gap1(G1)- Cells increase in size. The G1checkpointcontrol mechanism ensures that everything is ready for DNA synthesis. Synthesis(S)- DNA replication occurs during this phase. DNA Replication The process in which DNA makes a duplicate copy of itself. Semiconservative Replication The process in which the DNA molecule uncoils and separates into two strands. Each original strand becomes a template on which a new strand is constructed, resulting in two DNA molecules identical to the original DNA molecule. Gap 2(G2)- The cell continues to grow. The G2checkpointcontrol mechanism ensures that everything is ready to enter the M (mitosis) phase and divide. Mitotic(M) refers to the division of the nucleus. Cell growth stops at this stage and cellular energy is focused on the orderly division into daughter cells. A checkpoint in the middle of mitosis (Metaphase Checkpoint) ensures that the cell is ready to complete cell division. The final event is cytokinesis, in which the cytoplasm divides and the single parent cell splits into two daughter cells. Reproduction Cellular reproduction is a process by which cells duplicate their contents and then divide to yield multiple cells with similar, if not duplicate, contents. Mitosis Mitosis- nuclear division resulting in the production of two somatic cells having the same genetic complement (genetically identical) as the original cell. -

The Cell Cycle

CAMPBELL BIOLOGY IN FOCUS URRY • CAIN • WASSERMAN • MINORSKY • REECE 9 The Cell Cycle Lecture Presentations by Kathleen Fitzpatrick and Nicole Tunbridge, Simon Fraser University © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. SECOND EDITION Overview: The Key Roles of Cell Division . The ability of organisms to produce more of their own kind best distinguishes living things from nonliving matter . The continuity of life is based on the reproduction of cells, or cell division © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. In unicellular organisms, division of one cell reproduces the entire organism . Cell division enables multicellular eukaryotes to develop from a single cell and, once fully grown, to renew, repair, or replace cells as needed . Cell division is an integral part of the cell cycle, the life of a cell from its formation to its own division © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Figure 9.2 100 m (a) Reproduction 50 m (b) Growth and development 20 m (c) Tissue renewal © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Concept 9.1: Most cell division results in genetically identical daughter cells . Most cell division results in the distribution of identical genetic material—DNA—to two daughter cells . DNA is passed from one generation of cells to the next with remarkable fidelity © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Cellular Organization of the Genetic Material . All the DNA in a cell constitutes the cell’s genome . A genome can consist of a single DNA molecule (common in prokaryotic cells) or a number of DNA molecules (common in eukaryotic cells) . DNA molecules in a cell are packaged into chromosomes © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. Figure 9.3 20 m © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. -

Datasheet for CDK1-Cyclin B

of T161 is required for activation of the CDK1- Supplied in: 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES Specific Activity: ~1,000,000 units/mg cyclin B complex and is mediated by the CDK (pH 7.5 @ 25°C), 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.01% CDK1-cyclin B activating kinase (CAK). During G2 phase, Brij 35 and 50% glycerol. Molecular Weight: CDK1 (34 kDa), cyclin B CDK1-cyclin B complex is held in an inactive state (48 kDa). The apparent molecular weight of cyclin by phosphorylation of CDK1 at the two negative Reagents Supplied with Enzyme: B on SDS-PAGE is about 60 kDa. 1-800-632-7799 regulatory sites, T14 and Y15 by CDK1 inhibitory 10X NEBuffer for Protein Kinases (PK). [email protected] protein kinases, Myt1 and Wee1 respectively. Quality Control Assays www.neb.com Dephosphorylation of T14 and Y15 by cell division Reaction Conditions: 1X NEBuffer for PK (NEB Protease Activity: After incubation of 100 units #B6022), supplemented with 200 µM ATP (NEB P6020S 032120413041 cycle 25 (CDC25) protein phosphatase in late G2 of CDK1-cyclin B with a standard mixture phase activates the CDK1-cyclin B complex and #P0756) and gamma-labeled ATP to a final specific of proteins for 2 hours at 30°C, no proteolytic activity of 100–500 µCi/µmol. Incubate at 30°C. triggers the initiation of mitosis. During expression activity could be detected by SDS-PAGE analysis. P6020S in insect cells, the recombiniant CDK1-cyclin B is 1X NEBuffer for PK: Phosphatase Activity: After incubation of 200 units 20,000 U/ml Lot: 0321204 activated in vivo by endogenous kinase (1–4). -

Regulation of the Cell Cycle and DNA Damage-Induced Checkpoint Activation

RnDSy-lu-2945 Regulation of the Cell Cycle and DNA Damage-Induced Checkpoint Activation IR UV IR Stalled Replication Forks/ BRCA1 Rad50 Long Stretches of ss-DNA Rad50 Mre11 BRCA1 Nbs1 Rad9-Rad1-Hus1 Mre11 RPA MDC1 γ-H2AX DNA Pol α/Primase RFC2-5 MDC1 Nbs1 53BP1 MCM2-7 53BP1 γ-H2AX Rad17 Claspin MCM10 Rad9-Rad1-Hus1 TopBP1 CDC45 G1/S Checkpoint Intra-S-Phase RFC2-5 ATM ATR TopBP1 Rad17 ATRIP ATM Checkpoint Claspin Chk2 Chk1 Chk2 Chk1 ATR Rad50 ATRIP Mre11 FANCD2 Ubiquitin MDM2 MDM2 Nbs1 CDC25A Rad50 Mre11 BRCA1 Ub-mediated Phosphatase p53 CDC25A Ubiquitin p53 FANCD2 Phosphatase Degradation Nbs1 p53 p53 CDK2 p21 p21 BRCA1 Ub-mediated SMC1 Degradation Cyclin E/A SMC1 CDK2 Slow S Phase CDC45 Progression p21 DNA Pol α/Primase Slow S Phase p21 Cyclin E Progression Maintenance of Inhibition of New CDC6 CDT1 CDC45 G1/S Arrest Origin Firing ORC MCM2-7 MCM2-7 Recovery of Stalled Replication Forks Inhibition of MCM10 MCM10 Replication Origin Firing DNA Pol α/Primase ORI CDC6 CDT1 MCM2-7 ORC S Phase Delay MCM2-7 MCM10 MCM10 ORI Geminin EGF EGF R GAB-1 CDC6 CDT1 ORC MCM2-7 PI 3-Kinase p70 S6K MCM2-7 S6 Protein Translation Pre-RC (G1) GAB-2 MCM10 GSK-3 TSC1/2 MCM10 ORI PIP2 TOR Promotes Replication CAK EGF Origin Firing Origin PIP3 Activation CDK2 EGF R Akt CDC25A PDK-1 Phosphatase Cyclin E/A SHIP CIP/KIP (p21, p27, p57) (Active) PLCγ PP2A (Active) PTEN CDC45 PIP2 CAK Unwinding RPA CDC7 CDK2 IP3 DAG (Active) Positive DBF4 α Feedback CDC25A DNA Pol /Primase Cyclin E Loop Phosphatase PKC ORC RAS CDK4/6 CDK2 (Active) Cyclin E MCM10 CDC45 RPA IP Receptor -

Human P14arf-Mediated Cell Cycle Arrest Strictly Depends on Intact P53 Signaling Pathways

Oncogene (2002) 21, 3207 ± 3212 ã 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950 ± 9232/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/onc Human p14ARF-mediated cell cycle arrest strictly depends on intact p53 signaling pathways H Oliver Weber1,2, Temesgen Samuel1,3, Pia Rauch1 and Jens Oliver Funk*,1 1Laboratory of Molecular Tumor Biology, Department of Dermatology, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, 91052 Erlangen, Germany; 2Regulation of Cell Growth Laboratory, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Maryland, MD 21702-1201, USA The tumor suppressor ARF is transcribed from the INK4a/ 4 and 6 activities, thus leading to decreased phosphor- ARF locus in partly overlapping reading frames with the ylation of RB and to G1 arrest. Cells that are de®cient CDK inhibitor p16Ink4a. ARF is able to antagonize the for RB are resistant to p16Ink4a-mediated cell cycle MDM2-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of p53, arrest (Sherr and Roberts, 1995; Weinberg, 1995). leading to either cell cycle arrest or apoptosis, depending on ARF is also a cell cyle inhibitor. It does not directly the cellular context. However, recent data point to inhibit CDKs but interferes with the function of additional p53-independent functions of mouse p19ARF. MDM2 to destabilize p53. ARF may be activated by Little is known about the dependency of human p14ARF aberrant activation of oncoproteins such as Ras function on p53 and its downstream genes. Therefore, we (Palmero et al., 1998), c-myc (Zindy et al., 1998), analysed the mechanism of p14ARF-induced cell cycle arrest E1A (de Stanchina et al., 1998), Abl (Radfar et al., in several human cell types. -

Meiosis I and Meiosis II; Life Cycles

Meiosis I and Meiosis II; Life Cycles Meiosis functions to reduce the number of chromosomes to one half. Each daughter cell that is produced will have one half as many chromosomes as the parent cell. Meiosis is part of the sexual process because gametes (sperm, eggs) have one half the chromosomes as diploid (2N) individuals. Phases of Meiosis There are two divisions in meiosis; the first division is meiosis I: the number of cells is doubled but the number of chromosomes is not. This results in 1/2 as many chromosomes per cell. The second division is meiosis II: this division is like mitosis; the number of chromosomes does not get reduced. The phases have the same names as those of mitosis. Meiosis I: prophase I (2N), metaphase I (2N), anaphase I (N+N), and telophase I (N+N) Meiosis II: prophase II (N+N), metaphase II (N+N), anaphase II (N+N+N+N), and telophase II (N+N+N+N) (Works Cited See) *3 Meiosis I (Works Cited See) *1 1. Prophase I Events that occur during prophase of mitosis also occur during prophase I of meiosis. The chromosomes coil up, the nuclear membrane begins to disintegrate, and the centrosomes begin moving apart. The two chromosomes may exchange fragments by a process called crossing over. When the chromosomes partially separate in late prophase, until they separate during anaphase resulting in chromosomes that are mixtures of the original two chromosomes. 2. Metaphase I Bivalents (tetrads) become aligned in the center of the cell and are attached to spindle fibers.