CASTERTON Author: Emmeline Garnett Date of Draft: January 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

1 Victoria County History of Cumbria

Victoria County History of Cumbria Project: Work in Progress Interim Draft [Note: This is an interim draft and should not be cited without first consulting the VCH Cumbria project: for contact details, see http://www.cumbriacountyhistory.org.uk/ ] Parish/township: CASTERTON Author: Emmeline Garnett Date of draft: January 2014 SOCIAL HISTORY Until the 1830s Casterton’s social character appears to have been typical of other rural townships in Westmorland. The backbone of the community consisted of small farmers, many living in small hamlets or isolated dwellings. The township had no church and no proper village. The old manor house stood isolated and downgraded to a farm, and the inn was probably a recent establishment after the road was turnpiked. In 1695 it was reported that, ‘Wee have no person above the degree of a yeoman nor no person of £50 lands or £600 personal Estate within our township.’ 1 Change came with the establishment of the school which William Wilson Carus-Wilson founded as the Clergy Daughters’ School in Cowan Bridge, Lancashire, in 1823, 2 and ten years later moved with 90 pupils to custom-built premises at Casterton, providing a higher and more healthy site, which was moreover on his own family estate. 3 It is to Carus-Wilson’s credit that at a time when girls’ education had barely been considered, both his foundations were for girls. Even before the Clergy Daughters’ School, about 1820 he had started the Servants’ School, to instruct girls of a lower social class in basic household skills and a carefully restricted amount of general education. -

APPLY ONLINE the Closing Date for Applications Is Wednesday 15 January 2020

North · Lancaster and Morecambe · Wyre · Fylde Primary School Admissions in North Lancashire 2020 /21 This information should be read along with the main booklet “Primary School Admissions in Lancashire - Information for Parents 2020-21” APPLY ONLINE www.lancashire.gov.uk/schools The closing date for applications is Wednesday 15 January 2020 www.lancashire.gov.uk/schools This supplement provides details of Community, Voluntary Controlled, Voluntary Aided, Foundation and Academy Primary Schools in the Lancaster, Wyre and Fylde areas. The policy for admission to Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools is listed on page 2. For Voluntary Aided, Foundation Schools and Academies a summary of the admission policy is provided in this booklet under the entry for each school. Some schools may operate different admission arrangements and you are advised to contact individual schools direct for clarification and to obtain full details of their admission policies. These criteria will only be applied if the number of applicants exceeds the published admission number. A full version of the admission policy is available from the school and you should ensure you read the full policy before expressing a preference for the school. Similarly, you are advised to contact Primary Schools direct if you require details of their admissions policies. Admission numbers in The Fylde and North Lancaster districts may be subject to variation. Where the school has a nursery class, the number of nursery pupils is in addition to the number on roll. POLICIES ARE ACCURATE AT THE TIME OF PRINTING AND MAY BE SUBJECT TO CHANGE Definitions for Voluntary Aided and Foundation Schools and Academies for Admission Purposes The following terms used throughout this booklet are defined as follows, except where individual arrangements spell out a different definition. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Index to Gallery Geograph

INDEX TO GALLERY GEOGRAPH IMAGES These images are taken from the Geograph website under the Creative Commons Licence. They have all been incorporated into the appropriate township entry in the Images of (this township) entry on the Right-hand side. [1343 images as at 1st March 2019] IMAGES FROM HISTORIC PUBLICATIONS From W G Collingwood, The Lake Counties 1932; paintings by A Reginald Smith, Titles 01 Windermere above Skelwith 03 The Langdales from Loughrigg 02 Grasmere Church Bridge Tarn 04 Snow-capped Wetherlam 05 Winter, near Skelwith Bridge 06 Showery Weather, Coniston 07 In the Duddon Valley 08 The Honister Pass 09 Buttermere 10 Crummock-water 11 Derwentwater 12 Borrowdale 13 Old Cottage, Stonethwaite 14 Thirlmere, 15 Ullswater, 16 Mardale (Evening), Engravings Thomas Pennant Alston Moor 1801 Appleby Castle Naworth castle Pendragon castle Margaret Countess of Kirkby Lonsdale bridge Lanercost Priory Cumberland Anne Clifford's Column Images from Hutchinson's History of Cumberland 1794 Vol 1 Title page Lanercost Priory Lanercost Priory Bewcastle Cross Walton House, Walton Naworth Castle Warwick Hall Wetheral Cells Wetheral Priory Wetheral Church Giant's Cave Brougham Giant's Cave Interior Brougham Hall Penrith Castle Blencow Hall, Greystoke Dacre Castle Millom Castle Vol 2 Carlisle Castle Whitehaven Whitehaven St Nicholas Whitehaven St James Whitehaven Castle Cockermouth Bridge Keswick Pocklington's Island Castlerigg Stone Circle Grange in Borrowdale Bowder Stone Bassenthwaite lake Roman Altars, Maryport Aqua-tints and engravings from -

Beckgate Farmhouse £575,000

BECKGATE FARMHOUSE £575,000 Barbon, The Yorkshire Dales, LA6 2LT The quintessential country cottage. Incredibly charismatic and in an enviable village setting, this is an absolute ‘gem’. This delightful cottage is newly renovated in a gentle and sympathetic manner with great respect for the architectural features and history of this period property. A three storey home has been created offering four bedrooms and three reception rooms. Set within large established gardens of 0.30 acres (0.12 hectares) and enjoying lovely views of Barbon Fell with great parking provision - all in all, it’s a great place to embrace village life in this sought after Lune Valley village. A must see! www.davis-bowring.co.uk Welcome to BECKGATE FARMHOUSE £575,000 Barbon, The Yorkshire Dales, LA6 2LT There's no doubt about it, this is an utterly charming and beguiling country cottage. Offering well proportioned living space, period character features and a cracking village location. We’re hard pressed to choose our favourite thing, so here’s our (not so) short list for you to mull over… • For starters, this is indeed a rare opportunity - on the open market for the first time in over 60 years, the current owners bought the house privately last year and have carried out an extensive and truly sympathetic renovation programme (this included a new roof, a new heating and plumbing system, complete rewiring, newly plastered walls and ceilings amongst other things). They consciously introduced reclaimed materials as opposed to buying ‘new’ to enhance the period charm (the wooden kitchen floor, slate worktops and earthenware sink are great examples of this) and overhauled other elements (such as the sash windows, oak beams and lintels, oak and pine boarded doors) rather than imposing new on the structure. -

Open Zone Map in a New

Crosby Garrett Kirkby Stephen Orion Smardale Grasmere Raisbeck Nateby Sadgill Ambleside Tebay Kelleth Kentmere Ravenstonedale Skelwith Bridge Troutbeck Outhgill Windermere Selside Zone 1 M6 Hawkshead Aisgill Grayrigg Bowness-on-Windermere Bowston Lowgill Monday/Tuesday Near Sawrey Burneside Mitchelland Crook Firbank 2 Kendal Lunds Killington Sedburgh Garsdale Head Zone 2 Lake Crosthwaite Bowland Oxenholme Garsdale Brigsteer Wednesday Bridge Killington Broughton-in-Furness 1 Rusland Old Hutton Cartmel Fell Lakeside Dent Cowgill Lowick Newby Bridge Whitbarrow National Levens M6 Middleton Stone House Nature Reserve Foxfield Bouth Zone 3 A595 Backbarrow A5092 The Green Deepdale Crooklands Heversham Penny Bridge A590 High Newton A590 Mansergh Barbon Wednesday/Thursday Kirkby-in-Furness Milnthorpe Meathop A65 Kirksanton Lindale Storth Gearstones Millom Kirkby Lonsdale Holme A595 Ulverston Hutton Roof Zone 4 Haverigg Grange-over-Sands Askam-in-Furness Chapel-le-Dale High Birkwith Swarthmoor Arnside & Burton-in-Kendal Leck Cark Silverdale AONB Yealand Whittington Flookburgh A65 Thursday A590 Redmayne Ingleborough National Bardsea Nature Reserve New Houses Dalton-in-Furness M6 Tunstall Ingleton A687 A590 Warton Horton in Kettlewell Arkholme Amcliffe Scales Capernwray Ribblesdale North Walney National Zone 5 Nature Reserve A65 Hawkswick Carnforth Gressingham Helwith Bridge Barrow-in-Furness Bentham Clapham Hornby Austwick Tuesday Bolton-le-Sands Kilnsey A683 Wray Feizor Malham Moor Stainforth Conistone Claughton Keasden Rampside Slyne Zone 6 Morecambe -

For More Routes See

SEDBERGH TO KIRKBY LONSDALE Start/Finish Sedbergh or Kirkby Lonsdale Distance 24 miles (39km). Refreshments Sedbergh, Barbon and Kirkby Lonsdale Toilets Sedbergh, Kirkby Lonsdale Nearest train station Oxenholme near Kendal This is a gentle route exploring the lush Lune Valley connecting the two lively market towns of Sedbergh and Kirkby Lonsdale. 1. Leave Sedbergh on Finkle Street (by the church) signposted to Dent. Straight over mini-roundabout, cross the River Rawthey and then take the first turn on the right signed Sedbergh Golf Course. 2. Go past the golf course, up a short climb and through a gate. At a T-junction turn right. Through a second gate and pass Holme Open Farm. 3. At the junction with the main road, turn left. Follow this road passing under a railway bridge, then turn left by Middleton Hall. 4. Follow this lovely lane for 3.5 miles through to Barbon where there is a pub and the Churchmouse café. Turn left and climb through the village passing the church. Shortly after crossing the cattle grid turn sharp right signposted to Casterton and Kirkby Lonsdale. 5. Follow this road for two miles to where it swings right to cross the old railway. Turn left here signed Cowan Bridge. Take the second turn on the right signed Casterton. Go straight over at the cross roads to reach the A683. 6. Turn left and after 200m you reach a parking area and Devil’s Bridge. Cross this stunning old stone bridge, up past the toilets to reach the busy A65. Push a short distance along the pavement and turn right into Kirkby Lonsdale town centre. -

Election of City Councillors for The

NOTICE OF POLL Lancaster City Council Election of City Councillors for the Bare Ward NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT: 1. A POLL for the ELECTION of CITY COUNCILLORS for the BARE WARD in the said LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL will be held on Thursday 2 May 2019, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. Three City Councillors are to be elected in the said Ward. 3. The surnames in alphabetical order and other names of all persons validly nominated as candidates at the above-mentioned election with their respective places of abode and descriptions, and the names of all persons signing their nomination papers, are as follows: 1. NAMES OF CANDIDATES 2. PLACES OF ABODE 3. DESCRIPTION 4. NAMES OF PERSONS SIGNING NOMINATION PAPERS (surname first) ANDERSON, Tony 33 Russell Drive, Morecambe, LA4 Morecambe Bay Independents Geoffrey Knight Sarah E Knight Glenys P Dennison Ray Stallwood Geoffrey T Nutt 6NR Deborah A Knight Roger T Dennison Shirley Burns Sandra Stallwood Pauline Nutt BARBER, Stephie Cathryn 7 Kensington Court, Bare Lane, Conservative Party Candidate Julia A Tamplin James F Waite James C Fletcher John Fletcher Robin Seward Bare, Morecambe, LA4 6DH Charles Edwards Christine Waite Angela J Fletcher David P Madden Kathleen H Seward BUCKLEY, Jonathan James (Address in Lancaster) The Green Party Chloe A G Buckley Jeremy C Procter Richard L Moriarty Michael C Stocks Philip G Lasan Georgina J M Sommerville Patricia E Salkeld Kathryn M Chandler Julia C Lasan Joseph L Moore EDWARDS, Charles 12 Ruskin Drive, Morecambe, LA4 Conservative Party Candidate -

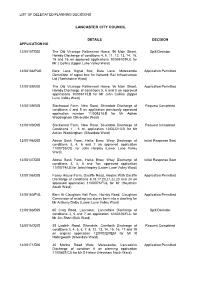

Delegated Planning Decisions PDF 34 KB

LIST OF DELEGATED PLANNING DECISIONS LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL DETAILS DECISION APPLICATION NO 12/00107/DIS The Old Vicarage Retirement Home, 56 Main Street, Split Decision Hornby Discharge of conditions 4, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 and 18 on approved applications 10/00610/FUL for Mr J Collins (Upper Lune Valley Ward) 12/00108/PAD Bare Lane Signal Box, Bare Lane, Morecambe Application Permitted Demolition of signal box for Network Rail Infrastructure Ltd (Torrisholme Ward) 12/00109/DIS The Old Vicarage Retirement Home, 56 Main Street, Application Permitted Hornby Discharge of conditions 5, 6 and 8 on approved applications 10/00611/LB for Mr John Collins (Upper Lune Valley Ward) 12/00139/DIS Slackwood Farm, New Road, Silverdale Discharge of Request Completed conditions 4 and 5 on application previously approved application number 11/00931/LB for Mr Adrian Waddingham (Silverdale Ward) 12/00140/DIS Slackwood Farm, New Road, Silverdale Discharge of Request Completed Conditions 1 - 5 on application 12/00221/LB for Mr Adrian Waddingham (Silverdale Ward) 12/00146/DIS Above Beck Farm, Helks Brow, Wray Discharge of Initial Response Sent conditions 3, 4, 6 and 7 on approved application 11/00733/CU. for John Harpley (Lower Lune Valley Ward) 12/00147/DIS Above Beck Farm, Helks Brow, Wray Discharge of Initial Response Sent conditions 3, 4, 6 and 7on approved application 11/00774/LB for John Harpley (Lower Lune Valley Ward) 12/00158/DIS Fanny House Farm, Oxcliffe Road, Heaton With Oxcliffe Application Permitted Discharge of conditions 6,15,17,20,21,22,23 -

Overtown Cable, Overtown, Cowan Bridge, Lancashire

Overtown Cable, Overtown, Cowan Bridge, Lancashire Archaeological Watching Brief Report Oxford Archaeology North May 2016 Electricity North West Issue No: 2016-17/1737 OA North Job No: L10606 NGR: SD 62944 76236 to SD 63004 76293 Overtown Cable, Overtown, Cowan Bridge, Lancashire: Archaeological Watching Brief 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................... 3 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Circumstances of Project .................................................................................... 4 1.2 Location, Topography and Geology ................................................................... 4 1.3 Historical and Archaeological Background ........................................................ 4 2. METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Project Design ..................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Watching Brief .................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Archive ................................................................................................................ 6 3. WATCHING BRIEF RESULTS ..................................................................................... -

Lancashire 1

Entries in red - require a photograph LANCASHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Rd No Parish Location Position LA_ALNH02 SD 9635 0120 A670 ASHTON UNDER LYNE Three Corner Nook S Mossley Cross in wall LA_ALNH03 SD 9759 0343 A670 ASHTON UNDER LYNE Quick jct S Quick LA_BBBO05 SD 7006 1974 A666 DARWEN Bolton rd,Whitehall by the rd LA_BBCL02 SD 68771 31989 A666 WILPSHIRE Whalley rd, Wilpshire 10m N of entrance to 'The Knoll' in wall LA_BBCL03 SD 69596 33108 A666 WILPSHIRE Near Anderton House Kenwood 162 LA_BBCL04 SD 70640 34384 A666 BILLINGTON AND LANGHO Langho; by No. 140 Whalley New rd against wall LA_BBCL06 SD 72915 35807 UC Rd BILLINGTON AND LANGHO W of Painter Wood Farm, outside Treetops built into wall LA_BCRD03 SD 8881 1928 A671 WHITWORTH by Facit Church against wall, immediately behind LA_BCRD03A SD 8881 1928 A671 WHITWORTH by Facit Church against wall LA_BCRD04 SD 8840 1777 A671 WHITWORTH Whitworth Bank Terrace (in rd!) LA_BCRD05A SD 8818 1624 A671 WHITWORTH Market Street; Whitworth against wall, immediately to left LA_BCRD05X SD 8818 1624 A671 WHITWORTH Market Street; Whitworth in wall LA_BCRT03 SD 8310 2183 A681 RAWTENSTALL by No. 649, Bacup rd, Waterfoot by boundary wall LA_BOAT07 SJ 7538 9947 B5211 ECCLES Worsley rd Winton by No405 in niche in wall LA_BOAT08 SJ 76225 98295 B5211 ECCLES Worsley rd at jcn Liverpool rd next to canal bridge LA_BOBY01a SD 7367 1043 UC Rd BOLTON Winchester Way 100m S jcn Blair Lane in wall Colliers Row rd 200m W of the cross rds with LA_BOCRR03 SD 68800 12620 UC Rd BOLTON Smithills Dean rd in the verge Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph LANCASHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Rd No Parish Location Position Chorley Old rd, 250m NW of the Bob Smithy LA_BOCY03 SD 67265 11155 B6226 BOLTON Inn, at the cross rds with Walker Fold rd / Old set in wall by Millstone pub opposite jcn Rivington Lane on LA_BOCY07 SD 61983 12837 A673 ANDERTON Grimeford verge LA_BOCY08 SD 60646 13544 A673 ANDERTON opp.