1 Victoria County History of Cumbria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPLY ONLINE the Closing Date for Applications Is Wednesday 15 January 2020

North · Lancaster and Morecambe · Wyre · Fylde Primary School Admissions in North Lancashire 2020 /21 This information should be read along with the main booklet “Primary School Admissions in Lancashire - Information for Parents 2020-21” APPLY ONLINE www.lancashire.gov.uk/schools The closing date for applications is Wednesday 15 January 2020 www.lancashire.gov.uk/schools This supplement provides details of Community, Voluntary Controlled, Voluntary Aided, Foundation and Academy Primary Schools in the Lancaster, Wyre and Fylde areas. The policy for admission to Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools is listed on page 2. For Voluntary Aided, Foundation Schools and Academies a summary of the admission policy is provided in this booklet under the entry for each school. Some schools may operate different admission arrangements and you are advised to contact individual schools direct for clarification and to obtain full details of their admission policies. These criteria will only be applied if the number of applicants exceeds the published admission number. A full version of the admission policy is available from the school and you should ensure you read the full policy before expressing a preference for the school. Similarly, you are advised to contact Primary Schools direct if you require details of their admissions policies. Admission numbers in The Fylde and North Lancaster districts may be subject to variation. Where the school has a nursery class, the number of nursery pupils is in addition to the number on roll. POLICIES ARE ACCURATE AT THE TIME OF PRINTING AND MAY BE SUBJECT TO CHANGE Definitions for Voluntary Aided and Foundation Schools and Academies for Admission Purposes The following terms used throughout this booklet are defined as follows, except where individual arrangements spell out a different definition. -

Election of City Councillors for The

NOTICE OF POLL Lancaster City Council Election of City Councillors for the Bare Ward NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT: 1. A POLL for the ELECTION of CITY COUNCILLORS for the BARE WARD in the said LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL will be held on Thursday 2 May 2019, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. Three City Councillors are to be elected in the said Ward. 3. The surnames in alphabetical order and other names of all persons validly nominated as candidates at the above-mentioned election with their respective places of abode and descriptions, and the names of all persons signing their nomination papers, are as follows: 1. NAMES OF CANDIDATES 2. PLACES OF ABODE 3. DESCRIPTION 4. NAMES OF PERSONS SIGNING NOMINATION PAPERS (surname first) ANDERSON, Tony 33 Russell Drive, Morecambe, LA4 Morecambe Bay Independents Geoffrey Knight Sarah E Knight Glenys P Dennison Ray Stallwood Geoffrey T Nutt 6NR Deborah A Knight Roger T Dennison Shirley Burns Sandra Stallwood Pauline Nutt BARBER, Stephie Cathryn 7 Kensington Court, Bare Lane, Conservative Party Candidate Julia A Tamplin James F Waite James C Fletcher John Fletcher Robin Seward Bare, Morecambe, LA4 6DH Charles Edwards Christine Waite Angela J Fletcher David P Madden Kathleen H Seward BUCKLEY, Jonathan James (Address in Lancaster) The Green Party Chloe A G Buckley Jeremy C Procter Richard L Moriarty Michael C Stocks Philip G Lasan Georgina J M Sommerville Patricia E Salkeld Kathryn M Chandler Julia C Lasan Joseph L Moore EDWARDS, Charles 12 Ruskin Drive, Morecambe, LA4 Conservative Party Candidate -

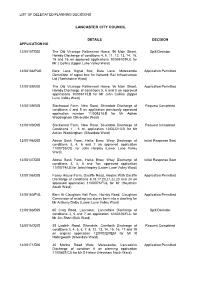

Delegated Planning Decisions PDF 34 KB

LIST OF DELEGATED PLANNING DECISIONS LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL DETAILS DECISION APPLICATION NO 12/00107/DIS The Old Vicarage Retirement Home, 56 Main Street, Split Decision Hornby Discharge of conditions 4, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 and 18 on approved applications 10/00610/FUL for Mr J Collins (Upper Lune Valley Ward) 12/00108/PAD Bare Lane Signal Box, Bare Lane, Morecambe Application Permitted Demolition of signal box for Network Rail Infrastructure Ltd (Torrisholme Ward) 12/00109/DIS The Old Vicarage Retirement Home, 56 Main Street, Application Permitted Hornby Discharge of conditions 5, 6 and 8 on approved applications 10/00611/LB for Mr John Collins (Upper Lune Valley Ward) 12/00139/DIS Slackwood Farm, New Road, Silverdale Discharge of Request Completed conditions 4 and 5 on application previously approved application number 11/00931/LB for Mr Adrian Waddingham (Silverdale Ward) 12/00140/DIS Slackwood Farm, New Road, Silverdale Discharge of Request Completed Conditions 1 - 5 on application 12/00221/LB for Mr Adrian Waddingham (Silverdale Ward) 12/00146/DIS Above Beck Farm, Helks Brow, Wray Discharge of Initial Response Sent conditions 3, 4, 6 and 7 on approved application 11/00733/CU. for John Harpley (Lower Lune Valley Ward) 12/00147/DIS Above Beck Farm, Helks Brow, Wray Discharge of Initial Response Sent conditions 3, 4, 6 and 7on approved application 11/00774/LB for John Harpley (Lower Lune Valley Ward) 12/00158/DIS Fanny House Farm, Oxcliffe Road, Heaton With Oxcliffe Application Permitted Discharge of conditions 6,15,17,20,21,22,23 -

Overtown Cable, Overtown, Cowan Bridge, Lancashire

Overtown Cable, Overtown, Cowan Bridge, Lancashire Archaeological Watching Brief Report Oxford Archaeology North May 2016 Electricity North West Issue No: 2016-17/1737 OA North Job No: L10606 NGR: SD 62944 76236 to SD 63004 76293 Overtown Cable, Overtown, Cowan Bridge, Lancashire: Archaeological Watching Brief 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................... 3 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Circumstances of Project .................................................................................... 4 1.2 Location, Topography and Geology ................................................................... 4 1.3 Historical and Archaeological Background ........................................................ 4 2. METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Project Design ..................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Watching Brief .................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Archive ................................................................................................................ 6 3. WATCHING BRIEF RESULTS ..................................................................................... -

Lancashire 1

Entries in red - require a photograph LANCASHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Rd No Parish Location Position LA_ALNH02 SD 9635 0120 A670 ASHTON UNDER LYNE Three Corner Nook S Mossley Cross in wall LA_ALNH03 SD 9759 0343 A670 ASHTON UNDER LYNE Quick jct S Quick LA_BBBO05 SD 7006 1974 A666 DARWEN Bolton rd,Whitehall by the rd LA_BBCL02 SD 68771 31989 A666 WILPSHIRE Whalley rd, Wilpshire 10m N of entrance to 'The Knoll' in wall LA_BBCL03 SD 69596 33108 A666 WILPSHIRE Near Anderton House Kenwood 162 LA_BBCL04 SD 70640 34384 A666 BILLINGTON AND LANGHO Langho; by No. 140 Whalley New rd against wall LA_BBCL06 SD 72915 35807 UC Rd BILLINGTON AND LANGHO W of Painter Wood Farm, outside Treetops built into wall LA_BCRD03 SD 8881 1928 A671 WHITWORTH by Facit Church against wall, immediately behind LA_BCRD03A SD 8881 1928 A671 WHITWORTH by Facit Church against wall LA_BCRD04 SD 8840 1777 A671 WHITWORTH Whitworth Bank Terrace (in rd!) LA_BCRD05A SD 8818 1624 A671 WHITWORTH Market Street; Whitworth against wall, immediately to left LA_BCRD05X SD 8818 1624 A671 WHITWORTH Market Street; Whitworth in wall LA_BCRT03 SD 8310 2183 A681 RAWTENSTALL by No. 649, Bacup rd, Waterfoot by boundary wall LA_BOAT07 SJ 7538 9947 B5211 ECCLES Worsley rd Winton by No405 in niche in wall LA_BOAT08 SJ 76225 98295 B5211 ECCLES Worsley rd at jcn Liverpool rd next to canal bridge LA_BOBY01a SD 7367 1043 UC Rd BOLTON Winchester Way 100m S jcn Blair Lane in wall Colliers Row rd 200m W of the cross rds with LA_BOCRR03 SD 68800 12620 UC Rd BOLTON Smithills Dean rd in the verge Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph LANCASHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Rd No Parish Location Position Chorley Old rd, 250m NW of the Bob Smithy LA_BOCY03 SD 67265 11155 B6226 BOLTON Inn, at the cross rds with Walker Fold rd / Old set in wall by Millstone pub opposite jcn Rivington Lane on LA_BOCY07 SD 61983 12837 A673 ANDERTON Grimeford verge LA_BOCY08 SD 60646 13544 A673 ANDERTON opp. -

1St Prize Spring Lambs from WA Jenkinson Realising £185.50

015242 61444/ 61246 (Sale Days) www.benthamauction.co.uk [email protected] WEEKLY NEWS 29TH MAY 2021 1st Prize Spring Lambs from WA Jenkinson realising £185.50 AUCTIONEERS: Stephen J Dennis Mobile: 07713 075 661 Greg MacDougall Mobile: 07713 075 664 Will Alexander Mobile: 07590 876 849 Office 015242 61444 Sale Days 61246 www.benthamauction.co.uk Wednesday 26th May FORTNIGHTLY DAIRY SALE 24 Forward Top Top Price From: Av J Robinson, Over Kellet & NC Hfrs £2150 £1743 S & CH Brennand, Ingleton NC Cows £1600 PW & DM Swindlehurst, Underbarrow £980 In Calf Hfrs £1800 W & R Mashiter, Roeburndale £1585 Auctioneer’s Report (Will Alexander): A nice line up of 13 heifers, saw the best sell to a top of £2150 on two occasions, firstly from Richard Robinson, Hoggetts Lane, with his Pedigree Heifer “Kelletview Twist Favourite”, 27days calved with a daily yield of 32litres, she was snapped up by Tom & Jonathon Pollock, Ainstable. Bentham local, Steven Brennand, later matched the top spot with his lovely Friesian type heifer, she headed home with Ian Askew, Kendal. Colin Birkett’s best to £1980, with the main of the others £1600-£1800. A run-of-the-mill entry of 5 cows, saw the best hit £1600 from Messrs Swindlehurst, with other older, 4th calved, cows either side of £900. A nice run of in calf heifers due June/July to the Angus, from Messers Mashiter, Harter- beck sold to a high of £1800, others £1720, £1750, to average £1585, another 6 from the same home in a fortnight. Next sale 9th June to include an entry of young stock from various farms, inc. -

High Park, Cowan Bridge, Lancashire

ry HIGH PARK, COWAN BRIDGBO LANCASHIRE Peter lles Over the summer of 1997 the Royal Commission on the Historic Monu:nents of England carried out an analyticai field survey of the archaeology of High Park, above Cowan Bridge, Lancashire. The site lies in the very north-east of the county bordering both Cumbria and Yorkshire, on the western edge of the Yorkshire Dales. The survey was undertaken at the request of Lancashire County Council, in order to identiff and record the surviving, visible, above ground archaeology of the area. Before the present investigations started, what was previously known of the archaeology of this area was derived chiefly from a survey conducted by R.A.C. Lowndes between 1960-l (Lowndes 1963). Lowndes identified five large Bronze Age burial mounds or tumuli (labelled TI to T5 on his accompanying plan), plus six settlement complexes (abelled A to F) sr.urounded by a system of 'Celtic' fields. On the evidence of pottery recovered from a small excavation of one of the settlements (Lowndes 1964) he suggested these and the fields were all Romano British in date. The RCHME survey has shown that the landscape is in fact much more complex and extensive than previously thought. It is now possible to say that humans have been living on and farming these hill sides - rather than simply burying their dead here - since the Bronze Age. Much of this activity, particularly on the lower slopes, has been masked or destroyed by later activity, but a type of field pattern typical of the later Bronze Age does sunrive in the north-east of the survey area, characterised by a mosaic of small plots and fields cleared out of stony ground, with the stone deposited into small caims or piled along plot edges. -

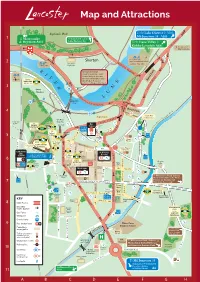

Map and Attractions

Map and Attractions 1 & Heysham to Lancaster City Park & Ride to Crook O’Lune, 2 Skerton t River Lune Millennium Park and Lune Aqueduct Bulk Stree N.B. Greyhound Bridge closed for works Jan - Sept. Skerton Bridge to become two-way. Other trac routes also aected. Please see Retail Park www.lancashire.gov.uk for details 3 Quay Meadow re Ay en re e Park G kat S 4 Retail Park Superstore Vicarage Field Buses & Taxis . only D R Escape H T Room R NO Long 5 Stay Buses & Taxis only Cinema LANCASTER VISITOR Long 6 INFORMATION CENTRE Stay e Gregson Th rket Street Centre Storey Ma Bashful Alley Sir Simons Arcade Long 7 Stay Long Stay Buses & Taxis only Magistrates 8 Court Long Stay 9 /Stop l Cruise Cana BMI Hospital University 10 Hospital of Cumbria visitors 11 AB CDEFG H ATTRACTIONS IN AND Assembly Rooms Lancaster Leisure Park Peter Wade Guided Walks AROUND LANCASTER Built in 1759, the emporium houses Wyresdale Road, Lancaster, LA1 3LA A series of interesting themed walks an eclectic mix of stalls. 01524 68444 around the district. Lancaster Castle lancasterleisurepark.com King Street, Lancaster, LA1 1LG 01524 420905 Take a guided tour and step into a 01524 414251 - GB Antiques Centre visitlancaster.org.uk/whats-on/guided- thousand years of history. lancaster.gov.uk/assemblyrooms Open 10:00 – 17:00 walks-with-peter-wade/ Adults £1.50, Children/OAP 75p, Castle Park, Lancaster, LA1 1YJ Tuesday–Saturday 10:00 - 16:30 Under 5s Free Various dates, start time 2pm. 01524 64998 Closed all Bank Holidays Trade Dealers Free Tickets £3 lancastercastle.com - Lancaster Brewery Castle Grounds open 09:30 – 17:00 daily King Street Studios Monday-Thursday 10:00 - 17:00 Lune Aqueduct Open for guided tours 10:00 – 16:00 Exhibition space and gallery showing art Friday- Sunday 10:00 – 18:00 Take a Lancaster Canal Boat Cruise (some restrictions, please check with modern and contemporary values. -

Forest of Bowland Landscape Character Assessment Was Being Undertaken, Consistency Has Been Sought Between Both Classifications

Forest of Bowland Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Landscape Character Assessment September 2009 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 Background 7 1.2 Purpose of the Assessment 11 1.3 Approach and Methodology 12 1.4 Structure of the Report 17 2.0 EVOLUTION OF THE LANDSCAPE 18 2.1 Introduction 18 2.2 Physical Influences on Landscape Character 18 2.3 Human and Cultural Influences on Landscape Character 31 2.4 The Landscape Today 43 3.0 LANDSCAPE CLASSIFICATION HIERARCHY 53 3.1 Introduction 53 3.2 National Landscape Context 53 3.3 Regional Landscape Context 53 3.4 County Landscape Context 56 3.5 The Forest of Bowland Landscape Classification 56 4.0 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS 64 4.1 Introduction 64 4.2 The Forest of Bowland Landscape in Overview 66 4.3 A: Moorland Plateaux 68 4.4 B: Unenclosed Moorland Hills 84 4.5 C: Enclosed Moorland Hills 102 4.6 D: Moorland Fringe 121 4.7 E: Undulating Lowland Farmland 147 4.8 F: Undulating Lowland Farmland with Wooded Brooks 163 4.9 G: Undulating Lowland Farmland with Parkland 176 4.10 H: Undulating Lowland Farmland with Settlement and Industry 195 4.11 I: Wooded Rural Valleys 206 4.12 J: Valley Floodplain 226 4.13 K: Drumlin Field 236 4.14 L: Rolling Upland Farmland 247 4.15 M: Forestry and Reservoir 254 4.16 N: Farmed Ridges 262 5.0 FUTURE FORCES FOR CHANGE 270 5.1 Introduction 270 5.2 Forces for Change 270 5.3 Landscape Tranquillity 276 6.0 MONITORING LANDSCAPE CHANGE 278 6.1 Introduction 278 6.2 The National Approach to Monitoring Landscape Change 278 6.3 Monitoring Landscape -

MORECAMBE LANCASTER City Centre

index to routes lancaster city centre stops morecambe town centre stops Destination Services Bus Station Town Centre Destination Services Bus Station Town Centre H Service Route Operator Leaflet lancaster bus station Stand Stops Stand Stops Morecambe Bus Station A Abbeystead 147 7 C, E L Lancaster Farms 18 6 C, E G 3 2 1 L O Ackenthwaite 555, 556 15 – Low Bentham 80 13 – MORECAMBE T R 2, 2A, Heysham - Morecambe - Lancaster - Hala - University STL 131 R E L D E Abraham Heights 71D M Marsh 71D A Morecambe R Q Town Hall R X2, (Serves Kingsway shops during shopping hours) T T Ambleside 555, 556 15 – Marshaw Road 28 20 C, D CENTRAL DRIVE N CE S S ET T Melling 81, 81B 13 – RE . Arkholme 81A 13 – 4 D T H A K S 3, 3A, Morecambe - Lancaster - University STL 130 Milnthorpe 555, 556 15 – O R C LA R ASDA 6A 17 – R C T C U Morecambe 40, 41, 6A 17 C, D L H X3, B Bare 3, 3A, 4 19 C, D N E A O H N R R C 3, 3A, 4 19 C, D I E . N Beaumont Bridge 55,55A,435,555,556 15 – R N D T . A M R 2, 2A 18 C, D C O F D Visitor M E N N Bilsborrow 40, 41 5 B, E J QU S TO R 4, Heysham - Morecambe - Lancaster - Hala Square - University STL 130 10 – Information E T L N E . U T O O R Blackpool 42 5 B, E Centre N P HOR N N O O Night Services Night Bus Stop M E NT O Queen T A RT S A Bolton–le–Sands 55,55A,435,555,556 15 – D WE Arndale S A R 5 Overton - Heysham - Morecambe - Carnforth STL 135 Nether Kellet 49 14 – T D RO H I Victoria U Shopping R E K Borwick 556 15 – IN P M E Centre R E S E 50 16 – A B T. -

Forest of Bowland AONB Landscape Character Assessment 2009

Craven Local Plan FOREST OF BOWLAND Evidence Base Compiled November 2019 Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Part I: Forest of Bowland AONB Landscape Character Assessment 2009 ...................................... 4 Part II: Forest of Bowland AONB Management Plan 2014-2019 February 2014 .......................... 351 Part III: Forest of Bowland AONB Obtrusive Lighting Position Statement ..................................... 441 Part IV: Forest of Bowland AONB Renewable Energy Position Statement April 2011 .................. 444 2 of 453 Introduction This document is a compilation of all Forest of Bowland (FoB) evidence underpinning the Craven Local Plan. The following table describes the document’s constituent parts. Title Date Comments FoB AONB Landscape Character September The assessment provides a framework Assessment 2009 for understanding the character and (Part I) future management needs of the AONB landscapes, and an evidence base against which proposals for change can be judged in an objective and transparent manner. FoB AONB Management Plan 2014-2019 February 2014 The management plan provides a (Part II) strategic context within which problems and opportunities arising from development pressures can be addressed and guided, in a way that safeguards the nationally important landscape of the AONB. In fulfilling its duties, Craven District Council should have regard to the Management Plan as a material planning consideration. FoB AONB Obtrusive Lighting Position N/A The statement provides guidance to all Statement AONB planning authorities and will assist (Part III) in the determination of planning applications for any development which may include exterior lighting. FoB AONB Renewable Energy Position April 2011 The statement provides guidance on the Statement siting of renewable energy developments, (Part IV) both within and adjacent to the AONB boundary. -

Around Kirkby Lonsdale a New Face for Kirkby September 2017

Monthly news and views of Christian Churches and community in the Rainbow Parish area; a Rainbow Parish production Around Kirkby Lonsdale A New Face for Kirkby September 2017 Recently opened, in a prime site in the middle of town, a new, expanded visitor information and gift shop - and it's already proving popular with the local community as well as those who visit. The Kirkby Lonsdale & Lune Valley Community Interest Company opened the new facility, in the former HSBC bank building, in June after protracted negotiations to acquire the lease. 'Moving from 24 Main Street to 29 Main Street sounds a relatively easy exercise,' said Tourism and Town Manager Sarah Ross. 'But it took our small team some considerable time and effort to make it happen. But it's been worth it because we have seen more people coming in to buy or to find out about our town, and coach parties are now mak- ing us their first port of call.' The new shop offers an expanded variety of gifts and sou- venirs, including a range of Tulchan clothing which spot- lights the architecture of the town. Help is offered to those seeking accommodation for a long or short stay, Sing at St Mary’s tickets can be booked for local attractions, and a series of guided town walks has proved particularly popular. St Mary’s choir would like to increase its members. Volunteers give up just a few hours a week to keep the We are a small group and we sing a service of premises open seven days a week.