Female Characters in the Films of Joachim Trier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Nordic Films Have Been Nominated for the Nordic Council Film Prize 2018

Press Release: Nordic Council Film Prize 2018 Published 21.8.2018, 13.30 CET FIVE NORDIC FILMS HAVE BEEN NOMINATED FOR THE NORDIC COUNCIL FILM PRIZE 2018 Haugesund International Film Festival, August 21, 2018 Today five films from the five Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden) have been announced as candidates for the Nordic Council Film Prize 2018 – a much coveted prize that will be awarded for the 15th time. In the field we see several well-known directors, such as Joachim Trier, Benedikt Erlingsson and Hlynur Pálmason, whose films have all premiered in some of the most important international film festivals in 2017 and 2018. The nominees for the Nordic Council Film Prize 2018 are: Denmark: Winter Brothers (Vinterbrødre) by Hlynur Pálmason (director / script), Julie Waltersdorph Hansen, Per Damgaard Hansen and Anton Máni Svansson (producers). Finland: Euthanizer (Armomurhaaja) by Teemu Nikki (director / script), Jani Pösö and Teemu Nikki (producers). Iceland: Woman at War (Kona fer í stríð) by Benedikt Erlingsson (director / script / producer), Ólafur Egill Egilsson (script), Marianne Slot and Carine Leblanc (producers). Norway: Thelma (Thelma) by Joachim Trier (director / script), Eskil Vogt (script) and Thomas Robsahm (producer). Sweden: Ravens (Korparna) by Jens Assur (director / script / producer), Jan Marnell and Tom Persson (producers). ABOUT THE NORDIC COUNCIL FILM PRIZE 2018 The purpose of the Nordic Council Film Prize, which is the most coveted award in the Nordic countries, is to raise interest in the Nordic cultural community as well as to recognise outstanding artistic initiatives. The films are selected and nominated because of their high artistic quality and originality, and for the way they combine and elevate the many elements of film into a compelling and holistic work of art in Nordic culture. -

Val Kilmer Documentary Charts Hollywood Rise and Fall

12 Established 1961 Lifestyle Features Sunday, July 11, 2021 he Cannes film festival has fallen gift for improvisation. “I could cut four of seen at Cannes-has also been praised for head over heels for a Norwegian film five different versions of any scene with the way it deals with the shifting gender Tabout a young woman trying to find her in this film. “I always wondered why power balance. In one particularly telling herself and the unknown actress who the hell is Norwegian film so messed up scene, Reinsve’s older graphic novelist plays her. “A star is born,” declared The that she hasn’t had a lead role yet?” Trier boyfriend crashes and burns when a radio Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw. Renate added. interview turns to the lumpen sexism of his Reinsve “takes off like a rocket and past creations. deserves star status to rival Lily James or Love in the time of #MeToo Trier said the film was navigating “the Alicia Vikander,” he added, giving “The Reinsve told AFP that she had “been beautiful chaos” and complications of love Worst Person in the World” a five-star through the same” labyrinth of self-doubt in a time of massive change. “With review-one of several it has already gar- and indecision as her character. And she #MeToo it is very polarized. But I believe nered. In her first big screen lead, Reinsve too would often think of herself as the that change also comes about through plays a twenty-something trying and failing worst person in the world as she saw oth- humanity and understanding,” he said. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis (Queeres*) Begehren und Behinderung* im Film „Thelma“ (2017, R: Joachim Trier) verfasst von / submitted by Alisa K. Simon, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2019 / Vienna 2019 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / UA 066 808 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Gender Studies degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Mag. Mag. Mag. Dr. Christopher Treiblmayr Danksagung Ich danke ganz herzlich meinem Betreuer Mag. Mag. Mag. Dr. Christopher Treiblmayr für die fantastische Betreuung inklusive wertvoller Tipps, Anregungen und Feedback. Vielen Dank auch an Marion Tara für die gegenseitige Unterstützung und Motivation während des Schreibprozesses, Jutta Berzborn für das Lektorat und Heike Simon für kontinuierliche Un- terstützung und Hilfe aller Art, ohne die diese Arbeit wohl niemals fertig geworden wäre. Nicht zuletzt geht ein großes Dankeschön an meine Eltern für ihre Geduld, ihre andauernde Un- terstützung und die vielen großen und kleinen Hilfen bei der Bewältigung dieses Studiums. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung .................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Relevanz und Forschungsstand .......................................................................... 2 1.2. Begriffsverwendungen -

Memory, Affect and the 'Sublime Image' in the Work of Joachim Trier

arts Article Louder Than Films: Memory, Affect and the ‘Sublime Image’ in the Work of Joachim Trier C. Claire Thomson Department of Scandinavian Studies, School of European Languages, Culture & Society, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK; [email protected] Received: 21 December 2018; Accepted: 17 April 2019; Published: 23 April 2019 Abstract: “We have to believe that new images are still possible”. This remark by Norwegian filmmaker Joachim Trier during a recent event in Oslo entitled ‘The Sublime Image’ speaks to the centrality in his work of images, often of trauma, that aspire to the condition of photographic stills or paintings. A hand against a window, cheerleaders tumbling against an azure sky, an infant trapped under a lake’s icy surface: these can certainly be read as sublime images insofar as we might read the sublime as an affect—a sense of the ineffable or the shock of the new. However, for Trier, cinema is an art of memory and here too, this article argues, his films stage an encounter with the temporal sublime and the undecidability of memory. Offering readings of Trier’s four feature films to date which center on their refraction of memory through crystal-images, the article emphasizes the affective encounter with the films as having its own temporality. Keywords: Joachim Trier; Norwegian cinema; affect in cinema; memory in cinema; the sublime 1. Introduction 1.1. Prologue: Oslo, Winter 2017 What I remember is the ice. Thick iridescent-grey sheets covering the streets, dimpled with yesterday’s footprints, studded with black grit, and self-renewing with every overnight snowfall and morning frost. -

Reprise Film Festival Official Selection, Competition

OFFICIAL SELECTION OFFICIAL SELECTION KARLOVY VARY TORONTO INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL REPRISE KARLOVY VARY TORONTO INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL OFFICIAL SELECTION, DISCOVERY COMPETITION SECTION REPRISE ity, about love is a and playful sorrow, film great about ambitions friendship, and madness the often and unpleas creativ ant clash between youthful presumptions and reality. With its somewhat un-Norwegian structure, REPRISE has a distinct style and narrative technique which moves the story forward in a rich - and enthusiastic manner. - 4 PRESENTS AJOACHIM TRIER FILM“REPRISE” STARRING ESPEN KLOUMAN HØINER ANDERS DANIELSEN LIE VIKTORIA WINGE ODD MAGNUS WILLIAMSON PÅL STOKKA CHRISTIAN RUBECK AND HENRIK ELVESTAD CASTING PRODUCTION COSTUME BYJAKOB RØRVIK DESIGN BYROGER ROSENBERG DESIGNERMARIA BOHLIN MAKE-UP DESIGN LINE ARTISTJUNE PAALGARD BYEIVIND STOUD PLATOU PRODUCERBENT ROGNLIEN SOUND MUSIC EDITED DESIGNERGISLE TVEITO BYOLA FLØTTUM BYOLIVIER BUGGE COUTTÉ Design: Fruitcake Oslo, Photos: Nils Vik DIRECTOR OF WRITTEN PHOTOGRAPHYJAKOB IHRE BYESKIL VOGT JOACHIM TRIER PRODUCED DIRECTED BYKARIN JULSRUD BYJOACHIM TRIER 4 PRESENTS “REPRISE” IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH FILMLANCE INTERNATIONAL AB, NORDISK FILM POST PRODUCTION AND NORSK FILMSTUDIO SUPPORTED BY NORWEGIAN FILM FUND, NORDISK FILM- & TV FUND AND SWEDISH FILM INSTITUTE “HAven’T WE TALKED ABOUT THIS BEFORE?” ERIK/ ESPEN KLOUMAN HØINER Espen Klouman Høiner plays Erik. He is a qualified advertising copywriter from Westerdal’s School of Communication. Among other film roles Espen acted in Petter Næss’ Bare Bea (Just Bea) Espen Klouman Høiner (Foto: Nils Vik) PHILLIP/ ANDERS DANIELSEN LIE Anders Danielsen Lie plays Phillip. He made his film-debut as Herman in the film of that name in 1990. At the moment is he finishing his medical studies at the University of Oslo. -

OSLO, AUGUST 31ST Is Norwegian Director Joachim Trier’S Second Feature Film

presents O SL O , A U G U ST 3 1ST A film by Joachim Trier Starring: Anders Danielsen Lie Official Selection: Un Certain Regard, Cannes Film Festival 2011 AFI Fest 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 Sundance Film Festival 2012 New Directors/New Films Festival 2012 San Francisco International Film Festival 2012 Country of Origin: Norway Format: 35mm/1.85/Color Sound Format: Dolby Digital Running Time: 95 minutes Genre: Drama Not Rated In Norwegian with English Subtitles NY/National Publicity Contact: LA/National Press Contact: Emma Griffiths Jenna Martin / Marcus Hu Emma Griffiths PR Strand Releasing Phone: 917. 806.0599 Phone: 310.836.7500 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Please download photos from our website: http://extranet.strandreleasing.com/secure/login.aspx?username=PRESS&password=STRAND SYNOPSIS Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie) will soon complete his drug rehabilitation in the countryside. As part of the program, he is allowed to go into the city for a job interview. Taking advantage of the leave, he stays in the city, drifting around, meeting people he hasn’t seen in a long time. At the age of 34, Anders is smart, handsome and from a good family, but deeply haunted by all the opportunities he has wasted, and the people he has let down. For the remainder of the day and long into the night, the ghosts of past mistakes will wrestle with the chance of love, the possibility of a new life and the hope of a different future by the time morning arrives. OSLO, AUGUST 31ST is Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s second feature film. -

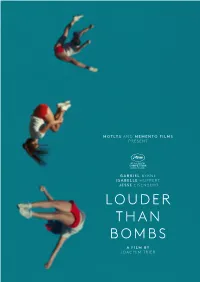

GABRIEL BYRNE ISABELLE HUPPERT JESSE EISENBERG a Film by Joachim Trier

GABRIEL BYRNE ISABELLE HUPPERT JESSE EISENBERG LOUDER THAN BOMBS A FILM BY JOACHIM TRIER MOTLYS AND MEMENTO FILMS PRESENT A FILM BY JOACHIM TRIER “LOUDER THAN BOMBS” GABRIEL BYRNE, JESSE EISENBERG, ISABELLE HUPPERT, DEVIN DRUID, RACHEL BROSNAHAN, RUBY JERINS, MEGAN KETCH WITH DAVID STRATHAIRN AND AMY RYAN CASTING LAURA ROSENTHAL SOUND DESIGN GISLE TVEITO EDITOR OLIVIER BUGGE COUTTE COMPOSER OLA FLØTTUM COSTUMES EMMA POTTER PRODUCTION DESIGN MOLLY HUGHES DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY JAKOB IHRE, FSF LINE Producer KATHRYN DEAN CO-PRODUCERS BO EHRHARDT, MIKKEL JERSIN EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS SIGVE ENDRESEN, FREDERICK W. GREEN, MICHAEL B. CLARK, EMILIE GEORGES, NICHOLAS SHUMAKER, NAIMA ABED, JOACHIM TRIER, ESKIL VOGT PRODUCED BY THOMAS ROBSAHM, JOSHUA ASTRACHAN, ALBERT BERGER & RON YERXA, MARC TURTLETAUB, ALEXANDRE MALLET-GUY WRITTEN BY ESKIL VOGT & JOACHIM TRIER DIRECTED BY JOACHIM TRIER A MOTLYS, MEMENTO FILMS PRODUCTION, NIMBUS FILM PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH ANIMAL KINGDOM, BEACHSIDE FILMS, MEMENTO FILMS DISTRIBUTION, MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL, BONA FIDE PRODUCTIONS IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH ARTE FRANCE CINEMA, DON’T LOOK NOW INTERNATIONAL SALES MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL GABRIEL BYRNE ISABELLE HUPPERT JESSE EISENBERG LOUDER THAN BOMBS A FILM BY JOACHIM TRIER MOTLYS AND MEMENTO FILMS PRESENT A FILM BY JOACHIM TRIER “LOUDER THAN BOMBS” GABRIEL BYRNE, JESSE EISENBERG, ISABELLE HUPPERT, DEVIN DRUID, RACHEL BROSNAHAN, RUBY JERINS, MEGAN KETCH WITH DAVID STRATHAIRN AND AMY RYAN CASTING LAURA ROSENTHAL SOUND DESIGN GISLE TVEITO EDITOR OLIVIER BUGGE COUTTE COMPOSER OLA FLØTTUM COSTUMES EMMA POTTER PRODUCTION DESIGN MOLLY HUGHES DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY JAKOB IHRE, FSF LINE Producer KATHRYN DEAN CO-PRODUCERS BO EHRHARDT, MIKKEL JERSIN EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS SIGVE ENDRESEN, FREDERICK W. GREEN, MICHAEL B. -

Québec Cinema at the Wisconsin Film Festival

Great Shades of Spring Season Premiere Writers write. We help New season begins April 2012! you start, polish, pitch. Check wpt.org for schedule and details. Online courses Screenplays, TV Pilots, Fiction, more The new season features interviews with Critiques & Consults local independent filmmakers followed by a presentation of their film. Writers’ Institute April 13-15 Write-by-the-Lake Retreat June 18-22 School of the Arts July 22-27 Be more independent www.dcs.wisc.edu/lsa/writing 608-262-3447 WISCONSIN PUBLIC TELEVISION City of Madison Department of Planningg Esther, are you sure you and Community & Economic know what you’re doing? the city can loan you money Oh, Shorty, you’re such WIFILMFEST.ORG • 877.963.FILM • WIFILMFEST.ORG to h i r e pr ofess i on als ! Development a good neighbor! And now present..... I can relax while getting 2012 • Grab That a loan at a great 2.75% rate! Loan! % Improve Your Home! • Energy Justst lookl at this • Windows • Insulation • Plumbing • Furnace Effi ciency great rate: 2.75 & Doors • Roofi ng • Electrical • Siding Upgrade WISCONSIN FILM FESTIVAL • MADISON • APRIL 18–22, 18–22, APRIL • MADISON • FESTIVAL FILM WISCONSIN Home Remodeling www.cityofmadison.com/homeloans 2 Loan 266-6557 • 266-4223 MADISON, WISCONSIN [ MARCH 25–31, 2012] film festival ((( SOUNDING ))) OUT THE ENVIRONMENT IN 30 FILMS ALL FILMS AND EVENTS ARE FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC. NO TICKETS REQUIRED. FEATURED EVENTS KEYNOTE: VAN JONES SEMPER FI: ALWAYS FAITHFUL THE CITY DARK Barrymore Theatre RACHEL LIBERT AND TONY HARDMON, U.S. (2011) IAN CHENEY, U.S. -

Un Film De Joachim Trier Eili Harboe Kaya Wilkins

UN FILM DE JOACHIM TRIER EILI HARBOE KAYA WILKINS UN FILM DE JOACHIM TRIER 116 MIN - NORVÈGE - 2017 - SCOPE - 5.1 SORTIE LE 22 NOVEMBRE DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE matilde incerti 5, rue Darcet Matériel presse téléchargeable sur assistée de julien cuvillier 75017 Paris www.le-pacte.com 28, rue Broca - 75005 Paris Tél. : 01 44 69 59 59 Tél. : 01 48 05 20 80 www.le-pacte.com [email protected] SYNOPSIS Thelma, une jeune et timide étudiante, vient de quitter la maison de ses très dévots parents, située sur la côte ouest de Norvège, pour aller étudier dans une université d’Oslo. Là, elle se sent irrésistiblement et secrètement attirée par la très belle Anja. Tout semble se passer plutôt bien mais elle fait un jour à la bibliothèque une crise d’épilepsie d’une violence inouïe. Peu à peu, Thelma se sent submergée par l’intensité de ses sentiments pour Anja, qu’elle n’ose avouer - pas même à elle-même, et devient la proie de crises de plus en plus fréquentes et paroxystiques. Il devient bientôt évident que ces attaques sont en réalité le symptôme de facultés surnaturelles et dangereuses. Thelma se retrouve alors confrontée à son passé, lourd des tragiques implications de ces pouvoirs. JOACHIM TRIER à propos de Thelma Les spectateurs qui sont habitués au naturalisme de vos même avons visionné bon nombre de gialli - ces films d’horreur précédents films -NOUVELLE DONNE, OSLO, 31 AOÛT et BACK italiens des années 70. Je me rappelle avoir aussi revu L’ÉCHELLE HOME - risquent d’être surpris avec ce thriller surnaturel.. -

Jakob Ihre, Fsf Director of Photography

JAKOB IHRE, FSF DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY FILM SPACEMAN OF BOHEMIA Director: Johan Renck Production Company: Free Association & Tango Entertainment & Netflix DISPATCHES FROM ELSEWHERE (Episode 1) Director: Jason Segel Production Scott Rudin Productions CHERNOBYL Director: Johan Renck Production Company: HBO & Sky Winner, Outstanding Cinematography for a Limited Series or Movie, Emmy Awards (2019) Winner, Best TV Limited Series or Motion Picture Made for TV, Golden Globe Awards (2019) Winner, Best Photography, Royal Television Society Craft Awards (2019) Winner, Best Cinematography – TV Drama, BSC Awards (2019) Winner, Sue Gibson Cinematography Award, National Film and Television School (2019) Official Selection, Camerimage Film Festival (2019) THELMA Director: Joachim Trier Production Company: Norwegian Film Institute Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2017) Official Selection, London Film Festival (2017) LOUDER THAN BOMBS Director: Joachim Trier Production Company: Bona Fide Productions Official Selection, Cannes Film Festival (2015) Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2015) LUX ARTISTS | 1 END OF THE TOUR Director: James Ponsoldt Production Company: Anonymous Content Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival (2015) Official Selection, London Film Festival (2015) OSLO, AUGUST 31ST Director: Joachim Trier Production Company: Strand Releasing Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival (2012) Official Selection, Cannes Film Festival (2011) Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2011) Winner, Best Cinematography, Stockholm -

4 De Marzo De 2016 Una Película De JOACHIM TRIER

una película de JOACHIM TRIER El cineasta de origen noruego Joachim Trier ( Reprise -2006- y Oslo, 31 recuerdan ellos del pasado e incluso de lo que fue el pasado mismo de la de agosto -20011-) propone, en su tercer largometraje, una visita al entorno mujer desaparecida. Así la historia se va reconstruyendo a base de fragmen - familiar, en este caso el formado por un padre y dos hijos de diferentes eda - tos que pueden provenir de ideas manifestadas, de fragmentos oníricos, de des, que soportan de muy distinta manera la pérdida de la esposa/madre ocu - monólogos interiores, de fotos e incluso de fragmentos del diario del menor rrida tres años atrás. de los hijos, leído en voz alta. El amor es más fuerte que las A través de todos estos elemen - bombas parece sustentarse en una tos, El amor es más fuerte que trama sencilla: los preparativos las bombas apuesta por un ela - que se llevan a cabo para preparar borado guión y un más elabora - una exposición, que servirá de do montaje. El primero es obra homenaje conmemorativo a la del colaborador habitual de mujer fallecida, una profesional Trier, Eskil Vogt , y el segundo del fotoperiodismo. Este aconte - responsabilidad del propio cimiento hará que se vuelvan a director noruego, que intenta reunir bajo el mismo techo sus que la densidad dramática de la dos hijos y su marido. historia quede sustentada gra - Trier le ha dado el papel del cias a su entramado formal y cabeza de familia a Gabriel sobre todo a un ambicioso y Byrne ( Spider, Leningrado, El variado reparto que ha sido capital ). -

Louder Than Bombs

MOTLYS AND MEMENTO FILMS PRESENT GABRIEL BYRNE ISABELLE HUPPERT JESSE EISENBERG LOUDER THAN BOMBS A FILM BY JOACHIM TRIER LOUDER THAN BOMBS A FILM BY JOACHIM TRIER GABRIEL BYRNE ISABELLE HUPPERT JESSE EISENBERG DEVIN DRUID RACHEL BROSNAHAN RUBY JERINS MEGAN KETCH WITH DAVID STRATHAIRN AND AMY RYAN MOTLYS AND MEMENTO FILMS PRESENT A MOTLYS MEMENTO FILMS PRODUCTION NIMBUS FILM PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH ANIMAL KINGDOM, BEACHSIDE FILMS, MEMENTO FILMSINTERNATIONAL, MEMENTO FILMS DISTRIBUTION, BONA FIDE PRODUCTIONS IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH ARTE FRANCE CINEMA DONT LOOK NOW WITH SUPPORT FROM NORWEGIAN FILMINSTITUTE, NORDISK FILM & TV FOND, DANSK FILMINSTITUTT, EURIMAGES. NORWAY-FRANCE-DENMARK | 109 MINS | 1.85 | 5.1 | COLOR LOUDER THAN BOMBS A FILM BY JOACHIM TRIER An upcoming exhibition celebrating photographer Isabelle Reed three years after her untimely death brings her eldest son Jonah back to the family house – forcing him to spend more time with his father Gene and withdrawn younger brother Conrad than he has in years. With the three of them under the same roof, Gene tries desperately to connect with his two sons, but they struggle to reconcile their feelings about the woman they remember so differently. JOACHIM TRIER (DIRECTOR) JOACHIM TRIER (b. 1974) is an internationally celebrated director and screenwriter. His critically acclaimed and award-winning feature filmsReprise (2006) and Oslo, August 31st (2011), both co-written with Eskil Vogt, have been invited to and won awards at international film festivals such as Cannes, Sundance, Toronto, Karlovy Vary, Gothenburg, Milan, and Istanbul. Oslo, August 31st was selected for Un Certain Regard at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011 and nominated for the César award for Best Foreign Film 2013 after reaching over 180 000 admissions at theatres in France.