Down Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orthotics Fact Sheet

Foundations of Pediatric Orthotics FACT The goal of this fact sheet is to provide a reference highlighting key points of orthotic management in children. Additional information on pediatric orthotic management can be located in the Atlas of Orthoses and Assistive Devices, edited by the American Acad- emy of Orthopedic Surgeons, and Lower Extremity Orthotic Intervention for the Pediatric SHEET Client in Topics in Physical Therapy: Pediatrics, edited by the American Physical Therapy Association. What Is an Orthosis? An orthosis is an external device with controlling forces to improve body alignment, improve function, immobilize the injured area, prevent or improve a deformity, protect a joint or limb, limit or reduce pain, and/or provide proprioceptive feedback. Orthoses are named for the part of the body they cover. Orthoses can be custom molded and custom fitted (custom fitted from prefabricated orthoses or off the shelf). Orthoses are classified as durable medical devices (DME) and require L-codes for insurance reimbursement. A prescription signed by a physician is usually required for insurance reimbursement for custom-molded and custom-fit orthoses. Who Designs and Provides Orthoses? • Certified orthotists have formal education in biomechanics and mate- rial sciences required in designing custom devices. They are nation- ally board certified, and 11 states require licensure to provide custom devices. There are approximately 3,000 certified orthotists in the US, with a limited number of orthotists specializing in pediatrics. Pediatric orthotists evaluate the child, cast the child, modify the mold, fabricate the orthosis, and custom fit the orthosis to the child. • Physical therapists are trained in the function of orthoses and will frequently fit and measure orthoses. -

Read Article (PDF)

Physical therapist for olympians brings HEADING ‘BEST IN CLASS’ to Cincinnati You don’t have to be an Olympic athlete to be treated like one. A evaluation. The time Doug dedicates to evaluating and listening to trip to ReActive Physical Therapy in Montgomery, will prove this to each patient provides him with an in depth understanding of how a be true. Motivated by his experiences working at the Olympic Train- variety of factors may be contributing to what may seem like an iso- ing Center and serving as a member of the Medical Staff at the Beijing lated problem. “Equipped with this un-derstanding I develop a unique and Lon-don Paralympic Games, Doug Rempe set out to bring the treatment plan that addresses each contributing factor,” says Rempe. same elite level of physical therapy and athletic training to Cincinnati Follow up treatments also provide one hour of one on one time with by founding ReActive Physical Therapy. Rempe. After each visit, personalized progress reports are emailed “Olympic athletes, and Paralympic athletes in particular, have to both patients and their physicians. unique physical challenges that require highly individualized care. Beyond his work with U.S. Paralympic and Olympic athletes, The Olympic Training Center provided the necessary time and re- Rempe has 18 years of experience as a physical therapist and athletic sources to deliver that level of care,” says Rempe. “People in Cincin- trainer in Cincinnati. This experience has equipped him with the nati are no different and deserve the same level of customized care that skills necessary to provide a broad range of services from injury as- I now provide through ReActive P.T. -

Outpatient Physical Therapy for a Toddler with Down

OUTPATIENT PHYSICAL THERAPY FOR A TODDLER WITH DOWN SYNDROME PRESENTING WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DELAYS A Doctoral Project A Comprehensive Case Analysis Presented to the faculty of the Department of Physical Therapy California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHYSICAL THERAPY by Sarah E. Christiansen SUMMER 2015 © 2015 Sarah E. Christiansen ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii OUTPATIENT PHYSICAL THERAPY FOR A TODDLER WITH DOWN SYNDROME PRESENTING WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DELAYS A Doctoral Project by Sarah E. Christiansen Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Katrin Mattern-Baxter __________________________________, First Reader Dr. Bryan Coleman-Salgado __________________________________, Second Reader Dr. Edward Barakatt ____________________________ Date iii Student: Sarah E. Christiansen I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. ___________________________, Department Chair ____________ Dr. Edward Barakatt Date Department of Physical Therapy iv Abstract of OUTPATIENT PHYSICAL THERAPY FOR A TODDLER WITH DOWN SYNDROME PRESENTING WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DELAYS by Sarah E. Christiansen A pediatric patient with Down Syndrome was seen for outpatient physical therapy treatment provided by a student for ten sessions from February to June 2014 at a university setting under the supervision of a licensed physical therapist. The patient was evaluated at the initial encounter with Peabody Developmental Motor Scale-2 and Gross Motor Function Measurement-88 and a plan of care was established. Main goals for the patient were to improve developmental motor functions through increasing functional strength, gait endurance and speed, improving balance, and independent ambulation of stairs. -

Standards of Practice for Physical Therapy

Standards of Practice for Physical Therapy HOD S06-20-35-29 [Amended: HOD S06-19-29-50; HOD S06-13-22-15; HOD S06-10-09-06; HOD S06-03-09-10; HOD 06-03-09-10; HOD 06-99-18-22; HOD 06-96-16-31; HOD 06-91-21- 25; HOD 06-85-30-56; Initial: HOD 06-80-04-04; HOD 06-80-03-03] [Standard] Preamble The physical therapy profession is committed to transforming society by optimizing movement to improve the human experience. Physical therapists pursue excellence in a professional scope of practice that includes optimizing physical function, health, quality of life, and well-being across the lifespan, and they work to improve population health in the communities where they practice. The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) attests to this commitment by adopting and promoting the following Standards of Practice for Physical Therapy. These standards are the profession’s statement of conditions and performances that are essential for provision of high-quality professional service to society, and they provide a foundation for assessment of physical therapist practice. I. Ethical/Legal Considerations A. Ethical Considerations The physical therapist practices according to the APTA Code of Ethics for the Physical Therapist. The physical therapist assistant complies with the APTA Standards of Ethical Conduct for the Physical Therapist ssistant. B. Legal Considerations The physical therapist complies with all the legal requirements of jurisdictions regulating the practice of physical therapy. The physical therapist assistant complies with all the legal requirements of jurisdictions regulating the work of the physical therapist assistant. -

Physical Therapy Service Delivered in the Polyclinic During the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games

Physical Therapy in Sport 36 (2019) 62e67 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Physical Therapy in Sport journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/ptsp Original Research Physical Therapy Service delivered in the Polyclinic During the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games Christiane S. Guerino Macedo a, b, Felipe F. Tadiello b, Leonardo T. Medeiros b, * Marcio C. Antonelo b, Marco A. Ferreira Alves b, c, Luciana D. Mendonça d, b, a Physical Therapy Department, State University of Londrina, Brazil b Sociedade Nacional de Fisioterapia Esportiva (SONAFE), Sao~ Paulo, Brazil c Physical Therapy Department, Universidade Santa Cecília (UNISANTA), Santos, Brazil d Physical Therapy Department, School of Biologic and Health Sciences, Universidade Federal dos Vales do Jequitinhonha e do Mucuri (UFVJM), Diamantina, Brazil article info abstract Article history: Objective: To characterize the Physical Therapy Services delivered at the Polyclinic during the Rio 2016 Received 10 August 2018 Paralympic Games. Received in revised form Design: Retrospective Cohort Study. 8 January 2019 Setting: Physical Therapy Services (PTS) of the Polyclinic. Accepted 10 January 2019 Participants: Athletes attended for Physical Therapy treatment at the Polyclinic during Rio 2016 Para- lympic Games. Keywords: Main outcome measures: The number of athletes treated, their nationalities, their sports modality, the Epidemiology Physical therapy modalities most frequently treated regions and the interventions applied. Rehabilitation Results: A total of 4504 interventions were delivered and 399 athletes were treated in the PTS. Athletes representing athletics and sitting volleyball were the most frequently attended for treatment. The main diagnoses were muscle tension and tendinopathy. Analgesia was the main purpose of treatment and myofascial release and electrotherapy was the most frequent interventions. -

Physical Therapy for Adolescents Thru Adulthood with Down Syndrome

Physical Therapy for Adolescents thru Adulthood with Down syndrome PATRICIA SHIMANEK, PT, DPT AND ANDREA GADSON, PT, MPT Andrea Gadson, PT, MPT is a Physical Therapist at Advocate-Aurora Lutheran General Hospital. She has been a Physical Therapist for 22 years with 20 of those years focused specifically on out patient sports ANDREA medicine. She has found a niche treating foot and ankle injuries and GADSON, PT, MPT had additional training in orthotics and foot wear. She graduated from Washington University in St. Louis Patricia Shimanek PT, DPT is a Physical therapy at Advocate- Aurora Lutheran General Hospital, and has been a PT for almost 30yrs. Graduated from Northwestern University in 1988 with a bachelors in PT and from PATRICIA Rosalind Franklin University in 2011 with her doctorate in Physical SHIMANEK PT, DPT Therapy. She has been treating Ortho/Sports Medicine clients for 28 years. She is also a parent with a 22 y. o. male with Down syndrome. Objectives 1. Understanding Medical issues in a person with Down syndrome 2. Understanding physical characteristics of a person with Down syndrome 3. Understanding gait tendencies, shoe wear and orthotics 4. Understanding why exercise/Physical Therapy is important 5. Functional Physical Therapy Goals Medical Issues There are multiple medial issues related to Down syndrome: 1. Heart Problems(50%) 2.Gastrointestinal Issues 12% 3. Umbilical hernias 4. Epilepsy 5. Orthopedic Issues 6. Ears, nose, and throat issues 7. Blood problems 8. Thyroid issues 4-18% 9. Eye Issues 10. Skin/dermatology concerns 11. Dental issues 12. Alzheimer’s 13. Obesity 14. Obstructive sleep apnea 50-79% 15. -

Hagerman Et Al 2008 TX of FXS Peds

Advances in the Treatment of Fragile X Syndrome Randi J. Hagerman, Elizabeth Berry-Kravis, Walter E. Kaufmann, Michele Y. Ono, Nicole Tartaglia, Ave Lachiewicz, Rebecca Kronk, Carol Delahunty, David Hessl, Jeannie Visootsak, Jonathan Picker, Louise Gane and Michael Tranfaglia Pediatrics 2009;123;378-390 DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-0317 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/123/1/378 PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright © 2009 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275. Downloaded from www.pediatrics.org at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS on December 30, 2008 REVIEW ARTICLE Advances in the Treatment of Fragile X Syndrome Randi J. Hagerman, MDa,b, Elizabeth Berry-Kravis, MD, PhDc,d,e, Walter E. Kaufmann, MD, PhDf, Michele Y. Ono, MSa,b, Nicole Tartaglia, MDg, Ave Lachiewicz, MDh,i, Rebecca Kronk, PhD, CRNPj,k, Carol Delahunty, MDl, David Hessl, PhDa,m, Jeannie Visootsak, MDn,o, Jonathan Picker, MDp,q, Louise Gane, MSa,b, Michael Tranfaglia, MDr aMIND. Institute and Departments of bPediatrics and mPsychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, Sacramento, California; -

Physical Therapy Interventions III - Prosthetics and Orthotics Unit

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Spring 1-2003 PT 569.01: Physical Therapy Interventions III - Prosthetics and Orthotics Unit Carrie Gajdosik University of Montana - Missoula Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Gajdosik, Carrie, "PT 569.01: Physical Therapy Interventions III - Prosthetics and Orthotics Unit" (2003). Syllabi. 4272. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/4272 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PT 569 – PT Interventions III: PROSTHETICS AND ORTHOTICS UNIT Spring semester 2003 March 31 Introduction to LE Amputation April 2 Components of LE Prosthesis by Doug Turner, Prosthetist 10-12 * Reading: O'Sullivan, Chapter 20 April 2 1 hour: Doug Turner, cont. 2-3 PM fac mtg April 4 Lab: prosthetic devices April 7 Lecture: Examination, Gait Abnormalities, & intervention of the LE Amputee * Reading: O'Sullivan, Chapter 19, * Optional - Videos on gait training on your own April 9 Continue Gait Abnormalities and intervention 10-12 * Review the Prosthetic Gait Training book April 9 Continue intervention 2-4 PM April 11 Case study April 14 UE Prosthetics - Doug Turner EVENING CLASS: Amputee Lab 6:40 to 8:30 PM April -

Impaired Wheelchair Mobility 625

Impaired Wheelchair Mobility 625 IMPAIRED WHEELCHAIR MOBILITY related to neuromuscular disorder or dysfunction Defi nition Limitation of independent operation of wheelchair within environment Assessment • Age and gender • Vital signs • History of neuromuscular disorder or dysfunction • Drug history • Musculoskeletal status, including coordination, gait, muscle size and strength, muscle tone, range of motion (ROM), and functional mobility as follows: 0 = completely independent 1 = requires use of equipment or device 2 = requires help, supervision, or teaching from another person 3 = requires help from another person and equipment or device 4 = dependent; doesn’t participate in activity • Neurologic status, including level of consciousness, motor ability, and sensory ability • Characteristics of patient’s wheelchair (e.g., whether standard or motorized) and ad- equacy of wheelchair for meeting patient’s needs (right size, appropriate safety features, and easy for patient to operate) • Endurance (length of time patient can operate wheelchair before becoming fatigued) Defi ning Characteristics • Postural instability during routine activities of daily living • Decreased reaction time • Diffi culty turning • Engages in substitutions for movement • Gait changes • Limited ability to perform gross motor skills • Limited ROM • Movement-induced shortness of breath • Movement-induced tremor • Slowed movement • Uncoordinated or jerky movements Expected Outcomes • Patient won’t exhibit complications associated with impaired wheelchair mobility, such as skin breakdown, contractures, venous stasis, thrombus formation, depression, altera- tion in health maintenance, and falls. • Patient will maintain or improve muscle strength and joint ROM. • Patient will achieve highest level of independence possible with regard to wheelchair use. • Patient will express feelings regarding alteration in ability to use wheelchair. • Patient will maintain safety when using wheelchair. -

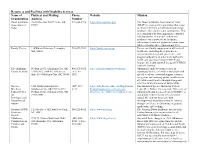

Download List of Resources and Facilities with Disability Services Here

Resources and Facilities with Disability Services Name of Physical and Mailing Phone Website Mission Organization Address Number Down Syndrome Post Office Box 54877 Tulsa, OK 918-804-3728 https://dsat.org/index.php The Down Syndrome Association of Tulsa Association of 74155 (DSAT) is a non-profit organization that exists Tulsa to enhance the lives of individuals with Down syndrome, their families and communities. This is accomplished by fostering positive attitudes and opportunities for people with Down syndrome via empowerment, inclusion, educational events and purposeful connections while celebrating their extraordinary lives. Family Voices 110 Hartwell Avenue, Lexington, 781-674-7224 https://familyvoices.org/ To increase family engagement at all levels of MA, 02421 health care, including direct patient care, organizational design and governance, and program and policy, in order to strengthen the health care systems serving CYSHCN and improve the health and well-being of CYSHCN and their families. The Oklahoma PO Box 21072, Oklahoma City, OK 405-271-5072 http://oklahomafamilynetwork.org/ Oklahoma Family Network focuses on Family Network 73156-1072 / 800 NE 15th Street, / 877-871- supporting families of children and youth with Suite 316 Oklahoma City, OK 73104 5072 special needs via emotional support, resource navigation, and ensuring quality healthcare for all children and families through strong and effective family/professional partnerships. The Lee 1200 North Stonewall Ave., (405) 271- https://alliedhealth.ouhsc.edu/Departments/ The -

Behavioral Challenges in Fragile X Syndrome

FRAGILE X CLINICAL & RESEARCH CONSORTIUM Consensus of the Fragile X Clinical & Research Consortium BEHAVIORAL CHALLENGES IN FRAGILE X SYNDROME First Published: June 2011 Last Updated: December 2018 fragilex.org/consensus BEHAVIORAL CHALLENGES IN FRAGILE X SYNDROME Introduction Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is a genetic condition that causes developmental disabilities in both males and females. Though FXS occurs in both genders, males are more frequently affected than females, and often with more severity. FXS is the most common cause of inherited intellectual disability and the most common-known single gene cause of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) that accounts for about 2-3 percent of all ASD cases. At this time, there is no medical test, such as a blood test or brain scan, which can diagnose ASD; rather it is diagnosed by interview and clinical observation. Anxiety, especially social phobia and specific phobias, as well as generalized anxiety, is very common in FXS and often disabling. FXS is a genetic disorder caused by a full mutation in the Fragile X Mental Retardation (FMR1) gene. Full mutations in FMR1 cause a deficit in Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP). This deficit in FMRP results in abnormal communication among brain cells, which in turn affects learning and behavior. In many, though not all cases, FXS causes a spectrum of behavioral conditions in affected individuals, which can be challenging to their families, peers, and teachers, and can limit their interactions and opportunities within the wider society. At this time, there is no cure for the condition; therefore, management of FXS is largely focused on treatment of the challenging behaviors. -

Title: Outpatient Physical Therapy Presence and Access in Medically Underserved Chicago Communities

TITLE: OUTPATIENT PHYSICAL THERAPY PRESENCE AND ACCESS IN MEDICALLY UNDERSERVED CHICAGO COMMUNITIES Introduction: Levels of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. continue to be reported as higher among racial and ethnic minorities than among the White population, suggesting a potentially higher demand for PT services among minorities. Similar trends of racial/ethnic health disparities that exist at the national level are also reflected in the City of Chicago. The majority of neighborhoods identified as medically underserved in Chicago are predominantly African American and Hispanic. The designated medically underserved areas receive safety net services that include free or Medicaid primary care, behavioral health and oral care. Aside from hospital facilities, there is limited/no mention of Physical Therapy (PT) services offered by safety net health facilities. Unpublished studies of PT presence in Chicago reported low or no outpatient PT services in several predominately African American neighborhoods. Purpose: This report describes the innovative application of geographic information systems (GIS) using publically available data to examine the presence of outpatient PT services in medically underserved Chicago communities. Methods: Study design: This is a mixed methods study designed to: 1) acquire georeferenced data to portray the current spatial distribution of outpatient PT services in six selected Chicago communities; 2) conduct focus groups to gather residents’ perspectives on the PT presence and accessibility in their communities. Procedures: Outpatient PT providers were identified though a Google search of PT clinics, health clinics, and hospitals in the selected neighborhoods. Identified providers were telephoned to confirm onsite PT services and record number of physical therapists employed full time and part time.