Notating Indie Culture: Aesthetics of Authenticity Aaron Joshua Klassen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Word from Régine Chassagne at Montreal’S MTELUS*

Our Philosphy KANPE is a We give the poorest communities in the Central Plateau a voice so that they can express their own needs, priorities, and foundation that goals. Our role is to help these communities to be supported by Haitian organizations who bring the complementary skills, brings support to knowledge, tools, and training necessary to provide guidance some of the most on the path to autonomy. Our Approach vulnerable families Haiti is flled with people who have talents and skills in many areas. We work to fnd the best local Haitian organizations in Haiti to help them and talents who can support these communities in attaining their goals in health, nutrition, education, agriculture, entre- achieve fnancial preneurship, and leadership. As a foundation, we ensure that funds are properly distributed autonomy, so that and that projects are carried out with respect for the goals of the community and according to strict norms of good they can “stand up”. governance and transparency. 2 Where KANPE works Baille Tourible Port-au-Prince 3 Since 2011, using an integrated approach on a focused geographical area, KANPE and its partners in Haiti are able to obtain tangible, sustainable results. Health & Nutrition Agriculture • A medical clinic serving over 11,000 • Distribution of bean seeds to 250 residents. We recorded more than farmers. 43,800 visits since opening in 2011. • Distribution of nearly 3,300 farm • More than 1,700 cases of cholera animals. treated since 2011. • Production of 12,000 fruit and • More than 1,000 Malaria tests are forest seedlings (Reforestation performed each year. -

MUSIC MADNESS BRACKETS NAME: Projected Winner

OnRecords' MARCH MUSIC MADNESS BRACKETS NAME: Projected Winner: S ROUND 1 ROUND 2 SWEET SIXTEEN ELITE EIGHT FINAL FOUR FINALIST CHAMPION FINALIST FINAL FOUR ELITE EIGHT SWEET SIXTEEN ROUND 2 ROUND 1 S 1 Kid A – Radiohead Dark Side of the Moon – Pink Floyd 1 16 Hot Fuss – Killers The Joshua Tree – U2 16 8 Is This It? - Strokes It Takes a Nation – Public Enemy 8 9 Rush of Blood - Coldplay Rhythm Nation – Janet Jackson 9 5 In Rainbows – Radiohead IV – Led Zeppelin 5 SINCE 2000 ConFerence 1970's-80's ConFerence 12 College Dropout – Kanye Wish You Were Here – Pink Floyd 12 4 Blueprint – Jay Z Rumours – Fleetwood Mac 4 13 Channel Orange – Frank Ocean Blue – Joni Mitchell 13 6 MBDTF – Kanye West London Calling – The Clash 6 11 White Blood Cells – White Stripes Who's Next – The Who 11 3 Funeral – Arcade Fire Doolittle – The Pixies 3 14 Mama's Gun – Erykah Badu Songs in the Key of Life 14 7 Elephant – The White Stripes What's Going On – Marvin Gaye 7 10 Fade to Black – Amy Winehouse Graceland – Paul Simon 10 2 21 - Adele Thriller – MJ 2 15 Royalty – Childish Gambino Purple Rain – Prince 15 1 Kind of Blue – Miles Davis OK Computer – Radiohead 1 16 Otis Blue – Otis Redding Blue Album – Weezer 16 8 Elvis Presley – Elvis Presley Achtung Baby – U2 8 9 I Never Loved a Man... - Aretha Miseducation of Lauryn Hill 9 5 A Love Supreme – John Coltrane Illmatic – Nas 5 12 Astral Weeks – Van Morrison The Score – Fugees 12 4 Revolver – Beatles Jagged Little Pill – Alanis 4 13 Time Out – Dave Brubeck Christina Aguilera's Self-Titled 13 6 Velvet Underground and Nico What's the Story.. -

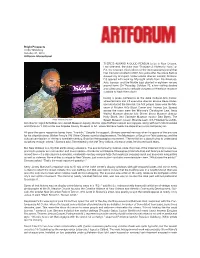

“Prospect 3: Notes for Now,” Or P.3, The

Bright Prospects Linda Yablonsky October 31, 2014 Artforum International THERE’S ALWAYS A GOOD REASON to be in New Orleans. Last weekend, the draw was “Prospect 3: Notes for Now,” or P.3, the resonant third edition of the international biennial that Dan Cameron created in 2007, two years after Hurricane Katrina doused city and spirit. Under artistic director Franklin Sirmans, P.3 opened with work by fi fty-eight artists from the Americas, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East planted in eighteen venues around town. On Thursday, October 23, a few visiting dealers and collectors joined a veritable congress of American museum curators to track them down. During a press conference at the Ashé Cultural Arts Center, where Sirmans and P.3 executive director Brooke Davis Ander- son introduced the biennial, the fi rst people I saw were the Mu- seum of Modern Art’s Stuart Comer and Thomas Lax. Spread across the room were the Whitney’s Christopher Lew, Andy Warhol Museum director Eric Shiner, Bronx Museum director Holly Block, and Carnegie Museum curator Dan Byers. The Artist Tavares Strachan Speed Museum curator Miranda Lash, ICA Philadelphia exhibi- tion director Ingrid Schaff ner, and Jewish Museum deputy director Jens Hoff mann would soon appear, along with both Rita Gonzalez and Christine Y. Kim of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where Sirmans heads the department of contemporary art. All gave the same reason for being there: “Franklin.” Despite the support, Sirmans seemed nervous when he spoke of the anchors for his citywide show: Walker Percy’s 1961 New Orleans novel of displacement, The Moviegoer; a Gaugin-in-Tahiti painting; and the cultural cannibalism of the early twentieth-century, Brazilian Antropofágico movement. -

Annual-Report-2016-2.Pdf

KANPE enables the Our Philosophy most vulnerable The Haitian population, identifying and expressing their own needs, is at the heart of our work. In our Haitian communities role as change agents serving this population, our to achieve financial role is to work with local partners and put in place autonomy so that plans to support their initiatives. they can “stand up”. Our Approach We work with Haitian partner organizations with complementary expertise, each of which brings knowledge, tools, and training necessary to help guide these communities on the path towards autonomy. These organizations have extensive track records and hold a very high level of credibility in their respective fields. Jean-Étienne Pierre and Isaac Pierre, two young members of the marching band, learning their lessons. 2 Since 2010, with the support of local partners, KANPE’s work has yielded significant results in the following fields: Health Education • Support for a medical clinic serving over • Financial support to 13 schools 11,000 residents. of Baille Tourible. • More than 1,500 cases of cholera treated. • Construction of 2 permanent shelters to accommodate 2 small schools. • More than 1,120 malaria tests performed. • Teacher training. Housing Leadership • 550 family homes received materials to conduct renovations and construct latrines. • Creation of a marching band for 45 young students from Baille Tourible. • Distribution of a basic water purification system to each family participating in the • Summer camp for 70 teenagers which Integrated Program. included 10 days of workshops and discussions on subjects like deforestation, Agriculture illiteracy, teenage pregnancy, and youth flight from rural areas. • Distribution of 7,500 pounds of bean seeds to 250 farmers. -

College Voice Vol. 31 No. 18

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 2006-2007 Student Newspapers 4-6-2007 College Voice Vol. 31 No. 18 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2006_2007 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "College Voice Vol. 31 No. 18" (2007). 2006-2007. 20. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2006_2007/20 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2006-2007 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. First Class • U.S. Postage PAID Permit #35 <- o e e oice New London, CT:' PUBUSflED WEEKLY BY THE STUDENTS OF CONNECTICUT COLLEGE VOLUME XXXI· NUMBER 18 FRIDAY, APRIL 6, 2007 CONNECTICUT COLLEGE, NEW LONDON, CT SAC Unveils Floralia Lineup __ OK Go, Girl Talk To Perform BY PAUL DRYDEN ances with the band's signature "geek rock outfits," a&e associate editor The campus is also eagerly anticipating Girl Talk, the stage SAC announced this spring's nanne for Gregg Gillis, who first Floralia lineup during a presentation reached the eyes and ears of Cannels at dinner in Harris this past Sunday with bis electrifying performance on night. Corning more than a month the docks in downtown New London before the actual Floralia date, as part of I Am Festival last Saturday, May 5, the lineup's head- September. Ever since then, Girl liners are some of the most notewor- Talk has been exploding across cann- thy in recent memory. -

2019 年 12 7 放送分 1. Getting Ready for Christmas Day / Paul Simon

2019 年 12 ⽉ 7 ⽇ 放送分 1. Getting Ready for Christmas Day / Paul Simon // So Beautiful Or So What 2. #9 Dream / John Lennon // Power To The People: The Hits 3. Playing Along / Norah Jones & Tarriona Tank Ball 4. Kay Granpa / Lakou Mizik feat. Tank and The Bangas // HaitiaNola 5. Loumandja / Lakou Mizik feat. Jon Cleary // HaitiaNola 6. Iko Kreyòl / Lakou Mizik feat. 79rs Gang & Regine Chassagne & Win Butler & Preservation Hall Jazz Band // HaitiaNola 7. Let's Stay Together / Tina Turner 8. A Change Is Gonna Come / B.E.F. feat. Tina Turner // Music Of Quality And Distinction Volume 2 9. A Song For You / B.E.F. feat. Mavis Staples // Music Of Quality And Distinction Volume 2 10. Money Don't Grow On Trees / Prince // 1999 (Super Deluxe Edition) 11. How Come U Don't Call Me Anymore? (Take 2) / Prince // 1999 (Super Deluxe Edition) 12. Purple Music / Prince // 1999 (Super Deluxe Edition) 13. Wonderful Remark / Van Morrison // At The Movies 14. I Hear You Paint Houses / Robbie Robertson w. Van Morrison // Sinematic 15. Cavan Potholes / Sharon Shannon & Band // Live in Minneapolis 2019 年 12 ⽉ 14 ⽇ 放送分 1. Where The Streets Have No Name (live) / U2 // The Joshua Tree Singles - Remastered and Live 2. Questions / Echo In The Canyon Feat. Jakob Dylan & Eric Clapton // Echo In The Canyon: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack 3. I Just Wasn't Made For These Times / Echo In The Canyon Feat. Jakob Dylan & Neil Young // Echo In The Canyon: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack 4. Sweet Thing / Van Morrison // Astral Weeks 5. Truckin’ / Grateful Dead // American Beauty 6. -

1 Arcade Fire

All Songs Considered Listeners Pick The Best Music Of 2010: The Top 100 1 Arcade Fire: The Suburbs 2 The Black Keys: Brothers 3 The National: High Violet 4 Mumford & Sons: Sigh No More 5 Broken Bells: Broken Bells 6 LCD Soundsystem: This Is Happening 7 Vampire Weekend: Contra 8 Sufjan Stevens: The Age Of Adz 9 Beach House: Teen Dream 10 Kanye West: My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy 11 Gorillaz: Plastic Beach 12 Sleigh Bells: Treats 13 Jonsi: Go 14 Local Natives: Gorilla Manor 15 Band Of Horses: Infinite Arms 16 The Tallest Man On Earth: The Wild Hunt 17 Deerhunter: Halcyon Digest 18 Spoon: Transference 19 Janelle Monae: The ArchAndroid 20 Yeasayer: Odd Blood 21 Ray LaMontagne and The Pariah Dogs: God Willin' and the Creek Don't Rise 22 New Pornographers: Together 23 Broken Social Scene: Forgiveness Rock Record 24 Joanna Newsom: Have One On Me 25 Cee Lo: The Ladykiller 26 MGMT: Congratulations 27 Sharon Jones And The Dap Kings: I Learned The Hard Way 28 Massive Attack: Heligoland 29 Josh Ritter: So Runs The World Away 30 Girl Talk: All Day 31 She And Him: Volume II 32 Bruce Springsteen: The Promise 33 Belle And Sebastian: Write About Love 34 Big Boi: Sir Lucious Left Foot: The Son Of Dusty Chico 35 Best Coast: Crazy For You 36 The White Stripes: Under Great White Northern Lights 37 Danger Mouse And Sparklehorse: Dark Night Of The Soul 38 Caribou: Swim 39 The Roots: How I Got Over 40 Kings Of Leon: Come Around Sundown 41 Frightened Rabbit: The Winter Of Mixed Drinks 42 Neil Young: Le Noise 43 Drive-By Truckers: The Big To-Do 44 Flying Lotus: Cosmogramma 45 Carolina Chocolate Drops: Genuine Negro Jig 46 Dead Weather: Sea of Cowards 47 Laura Veirs: July Flame 48 The Walkmen: Lisbon 49 Dr. -

Adventures in Film Music Redux Composer Profiles

Adventures in Film Music Redux - Composer Profiles ADVENTURES IN FILM MUSIC REDUX COMPOSER PROFILES A. R. RAHMAN Elizabeth: The Golden Age A.R. Rahman, in full Allah Rakha Rahman, original name A.S. Dileep Kumar, (born January 6, 1966, Madras [now Chennai], India), Indian composer whose extensive body of work for film and stage earned him the nickname “the Mozart of Madras.” Rahman continued his work for the screen, scoring films for Bollywood and, increasingly, Hollywood. He contributed a song to the soundtrack of Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006) and co- wrote the score for Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007). However, his true breakthrough to Western audiences came with Danny Boyle’s rags-to-riches saga Slumdog Millionaire (2008). Rahman’s score, which captured the frenzied pace of life in Mumbai’s underclass, dominated the awards circuit in 2009. He collected a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for best music as well as a Golden Globe and an Academy Award for best score. He also won the Academy Award for best song for “Jai Ho,” a Latin-infused dance track that accompanied the film’s closing Bollywood-style dance number. Rahman’s streak continued at the Grammy Awards in 2010, where he collected the prize for best soundtrack and “Jai Ho” was again honoured as best song appearing on a soundtrack. Rahman’s later notable scores included those for the films 127 Hours (2010)—for which he received another Academy Award nomination—and the Hindi-language movies Rockstar (2011), Raanjhanaa (2013), Highway (2014), and Beyond the Clouds (2017). -

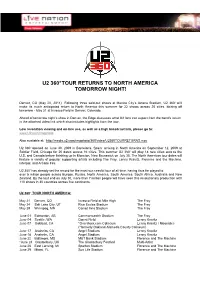

U2 360 RETURNS 5.20.11 FINAL V2 for LN.Com and Email Blast Follwed

U2 360° TOUR RETURNS TO NORTH AMERICA TOMORROW NIGHT! Denver, CO (May 20, 2011) Following three sold-out shows at Mexico City’s Azteca Stadium, U2 360° wil l make its much anticipated return to North America this summer for 22 shows across 20 cities, kicking off tomorrow - May 21 at Invesco Field in Denver, Colorado. Ahead of tomorrow night’s show in Denver, the Edge discusses what U2 fans can expect from the band’s return in the attached video link which also includes highlights from the tour. Low resolution viewing and on-line use, as well as a high broadcast link, please go to: www.U2.com/rmpphoto Also available at: http://media.u2.com/rmpphoto/360/video/U2360TOURRETURNS.mov U2 360° opened on June 30, 2009 in Barcelona, Spain arriving in North America on September 12, 2009 at Soldier Field, Chicago for 20 dates across 16 cities. This summer U2 360° will play 18 new cities acro ss the U.S. and Canada before finishing up in Moncton, New Brunswick on July 30. The North American tour dates will feature a variety of popular supporting artists including The Fray, Lenny Kravitz, Florence and the Machine, Interpol, and Arcade Fire. U2 360° has already set the record for the most suc cessful tour of all time, having thus far played to over 5 million people across Europe, Russia, North America, South America, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. By the tour end on July 30, more than 7 million people will have seen this revolutionary production with 110 shows in 30 countries across five continents. -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22.00 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15.00 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23.00 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38.00 Abbey Road (50th Anniversary) £ 27.00 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25.00 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17.00 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20.00 AC/DC- The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20.00 Adele - 21 £ 19.00 Aerosmith- Done With Mirrors £ 25.00 Air- Moon Safari £ 26.00 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20.00 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 17.00 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21.00 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16.00 Altered Images- Greatest Hits £ 20.00 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20.00 Andrew W.K. - You're Not Alone (2 LP) £ 20.00 ANTAL DORATI - LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA - Stravinsky-The Firebird £ 18.00 Antonio Carlos Jobim - Wave (LP + CD) £ 21.00 Arcade Fire - Everything Now (Danish) £ 18.00 Arcade Fire - Funeral £ 20.00 ARCADE FIRE - Neon Bible £ 23.00 Arctic Monkeys - AM £ 24.00 Arctic Monkeys - Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino £ 23.00 Aretha Franklin - The Electrifying £ 10.00 Aretha Franklin - The Tender £ 15.00 Asher Roth- Asleep In The Bread Aisle - Translucent Gold Vinyl £ 17.00 B.B. -

Pitchfork Media's Textual and Cultural Impact

CREATING A CULTURE: PITCHFORK MEDIA‘S TEXTUAL AND CULTURAL IMPACT ON ROLLING STONE MAGAZINE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri- Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by EMILY BRASHER Dr. Stephanie Craft, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2013 The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled CREATING A CULTURE: PITCHFORK MEDIA‘S TEXTUAL AND CULTURAL IMPACT ON ROLLING STONE MAGAZINE Presented by Emily Brasher A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts And hereby certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Stephanie Craft Professor Mary Kay Blakely Professor Andrew Hoberek Professor Lynda Kraxberger To my family, for always believing in me. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Stephanie Craft for all of her support and patience though this process. The road was long—there were a few address changes and even a name change along the way—but Dr. Craft spurred me on until the journey reached a happy end. My deepest thanks also to Dr. Mary Kay Blakely, Dr. Andrew Hoberek, and Dr. Lynda Kraxberger, for bearing with me through it all. Thanks to Dr. Betty Winfield for getting me started, and to Ginny Cowell and Martha Pickens for their invaluable advice and help. ii CREATING A CULTURE: PITCHFORK MEDIA‘S TEXTUAL AND CULTURAL IMPACT ON ROLLING STONE MAGAZINE Emily Brasher Dr. Stephanie Craft, Thesis Supervisor ABSTRACT The main purpose of this research is to demonstrate how cultures and subcultures can be created and disseminated through media, and how newer forms of media such as websites can have a tangible effect on the content of older forms of media such as print magazines. -

Quadrophonic News Issue 7

Major Album Releases In The Fourth Quarter, 2013: Reflektor -Arcade Fire October 29th, 2013 Artpop -Lady Gaga November 11th, 2013 Live on the BBC Vol. 2 -The Beatles November 11th, 2013 •New -Paul McCartney •Beyoncé -Beyoncé •Matangl -M.I.A. •Because The Internet QUADROPHONIC NEWS •Shangri La -Jake Bugg -Childish Gambino Quadrophonic News December 2013 Issue 7 Female Artists: A Reflection In This Month’s Issue: There's a lot to be said for any vocalist with a truly amazing • Album Reviews: Reflektor, Yeezus, Centipede Hz, voice, but there's undeniably something special about a woman with a MMLP2, Live Through This, Bleach, Night Time, powerful voice and monumental skill in writing. So in this article I hope My Time to pay tribute to some of the best female vocalists/song writers out there. It's a big category so, unfortunately I won't be able to get to every one • Insight On Famous Female Artists I’d like to, but I hope to cover three of my favorites. • December/January Music Event Calendar First up is Patty Griffin. Patty is a powerful song writer from Old Town, Maine. her musical style is hard to pin down but it lands somewhere between folk and rock. Her voice is one of incredible range, Arcade Fire’s Reflektor Review her voice can convey every emotion you can imagine, softly or loudly, Achtung Baby. OK Computer. Sound of Silver. sweetly or harshly, and this amazing voice is accompanied by her Elephant. All of these albums are special. You remember indomitable talent for song writing.