Vivaldi's Concerto in D Minor, Op. 3 No. 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Question of the Baroque Instrumental Concerto Typology

Musica Iagellonica 2012 ISSN 1233-9679 Piotr WILK (Kraków) On the question of the Baroque instrumental concerto typology A concerto was one of the most important genres of instrumental music in the Baroque period. The composers who contributed to the development of this musical genre have significantly influenced the shape of the orchestral tex- ture and created a model of the relationship between a soloist and an orchestra, which is still in use today. In terms of its form and style, the Baroque concerto is much more varied than a concerto in any other period in the music history. This diversity and ingenious approaches are causing many challenges that the researches of the genre are bound to face. In this article, I will attempt to re- view existing classifications of the Baroque concerto, and introduce my own typology, which I believe, will facilitate more accurate and clearer description of the content of historical sources. When thinking of the Baroque concerto today, usually three types of genre come to mind: solo concerto, concerto grosso and orchestral concerto. Such classification was first introduced by Manfred Bukofzer in his definitive monograph Music in the Baroque Era. 1 While agreeing with Arnold Schering’s pioneering typology where the author identifies solo concerto, concerto grosso and sinfonia-concerto in the Baroque, Bukofzer notes that the last term is mis- 1 M. Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, New York 1947: 318– –319. 83 Piotr Wilk leading, and that for works where a soloist is not called for, the term ‘orchestral concerto’ should rather be used. -

Apollo's Fire

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Saturday, November 9, 2013, 8pm Johann David Heinichen (1683–1789) Selections from Concerto Grosso in G major, First Congregational Church SeiH 213 Entrée — Loure Menuet & L’A ir à L’Ita lien Apollo’s Fire The Cleveland Baroque Orchestra Heinichen Concerto Grosso in C major, SeiH 211 Jeannette Sorrell, Music Director Allegro — Pastorell — Adagio — Allegro assai Francis Colpron, recorder Kathie Stewart, traverso PROGRAM Debra Nagy, oboe Olivier Brault, violin Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) “Brandenburg” Concerto No. 3 in G major, BWV 1048 Bach “Brandenburg” Concerto No. 4 in G major, BWV 1049 Allegro — Adagio — Allegro Allegro — Andante — Presto Olivier Brault, violin Bach “Brandenburg” Concerto No. 5 in D major, Francis Colpron & Kathie Stewart, recorders BWV 1050 Allegro Affettuoso The Apollo’s Fire national tour of the “Brandenburg” Concertos is made possible by Allegro a generous grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Jeannette Sorrell, harpsichord Apollo’s Fire’s CDs, including the complete “Brandenburg” Concertos, are for sale in the lobby. Olivier Brault, violin The artists will be on hand to sign CDs following the concert. Kathie Stewart, traverso INTERMISSION Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 16 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 17 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES a mountaintop experience: extraordinary power to move, delight, and cap- Concerto No. 5 requires from the harpsi- performing concertos for the virtuoso bands of europe tivate audiences for 250 years. But what is it that chordist a level of speed in the scalar passages gives them that power—that greatness that we that far exceeds anything else in the repertoire. -

MTO 0.7: Alphonce, Dissonance and Schumann's Reckless Counterpoint

Volume 0, Number 7, March 1994 Copyright © 1994 Society for Music Theory Bo H. Alphonce KEYWORDS: Schumann, piano music, counterpoint, dissonance, rhythmic shift ABSTRACT: Work in progress about linearity in early romantic music. The essay discusses non-traditional dissonance treatment in some contrapuntal passages from Schumann’s Kreisleriana, opus 16, and his Grande Sonate F minor, opus 14, in particular some that involve a wedge-shaped linear motion or a rhythmic shift of one line relative to the harmonic progression. [1] The present paper is the first result of a planned project on linearity and other features of person- and period-style in early romantic music.(1) It is limited to Schumann's piano music from the eighteen-thirties and refers to score excerpts drawn exclusively from opus 14 and 16, the Grande Sonate in F minor and the Kreisleriana—the Finale of the former and the first two pieces of the latter. It deals with dissonance in foreground terms only and without reference to expressive connotations. Also, Eusebius, Florestan, E.T.A. Hoffmann, and Herr Kapellmeister Kreisler are kept gently off stage. [2] Schumann favours friction dissonances, especially the minor ninth and the major seventh, and he likes them raw: with little preparation and scant resolution. The sforzato clash of C and D in measures 131 and 261 of the Finale of the G minor Sonata, opus 22, offers a brilliant example, a peculiarly compressed dominant arrival just before the return of the main theme in G minor. The minor ninth often occurs exposed at the beginning of a phrase as in the second piece of the Davidsbuendler, opus 6: the opening chord is a V with an appoggiatura 6; as 6 goes to 5, the minor ninth enters together with the fundamental in, respectively, high and low peak registers. -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

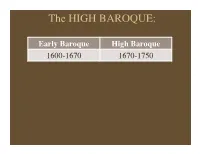

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

AP Music Theory: Unit 2

AP Music Theory: Unit 2 From Simple Studies, https://simplestudies.edublogs.org & @simplestudiesinc on Instagram Music Fundamentals II: Minor Scales and Key Signatures, Melody, Timbre, and Texture Minor Scales ● Natural Minor ○ No accidentals are changed from the relative minor’s key signature ○ Scale Pattern: W H W W H W W (W=whole note; H=half note) ○ Solfege: Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do ○ Scale Degrees: 1 2 b3 4 5 b6 b7 8 ● Harmonic Minor ○ The seventh scale degree is raised (it becomes the leading tone) ○ Scale Pattern: W H W W H m3 H ○ Solfege: Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do ○ Scale Degrees: 1 2 b3 4 5 b6 7 8 ● Melodic Minor ○ Ascending: the sixth and seventh degrees are raised ○ Descending: it becomes natural minor (meaning that the sixth and seventh degrees are no longer raised) ○ Scale Pattern (Ascending): W H W W W W H ○ Solfege (Ascending): Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do ○ Solfege (Descending): Do Te Le Sol Fa Mi Re Do ○ Scale Degrees (Ascending): 1 2 b3 4 5 6 7 8 ● Minor Pentatonic Scale ○ 5-note minor scale (made of the 5 diatonic pitches) ○ Scale Pattern: m3 W W m3 W ○ Solfege: Do Mi Fa Sol Te Do ○ Scale Degrees 1 b3 4 5 b7 8 Key Relationships ● Parallel Keys ○ Keys that share a tonic ○ One major and one minor ■ Example: d minor and D major are parallel keys because they share the same tonic (D) ● Relative Keys ○ Keys that share a key signature (but have different tonics) ■ Example: a minor and C major are relative keys (since they both don’t have any sharps or flats) ● Closely Related Keys ○ Keys that differ from each other by at most -

Juilliard415 Robert Mealy , Director and Violin Eunji Lee , Harpsichord

Friday Evening, December 8, 2017, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard415 Robert Mealy , Director and Violin Eunji Lee , Harpsichord The Pleasure Garden: Music From Handel’s London GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759) Concerto grosso in G major, Op. 6, No. 1, from Twelve Grand Concertos in Seven Parts , Op. 6 (1740) A tempo giusto Allegro e forte Adagio Allegro Allegro ROBERT MEALY and SARAH JANE KENNER , Violin Concertino MORGAN LITTLE , Cello Concertino HANDEL Concerto grosso in B-flat major, Op. 6, No. 7 , HWV 325 (1739) Largo Allegro Largo Andante Hornpipe MICHAEL CHRISTIAN FESTING (1705–52) Concerto in G major, Op. 3, No. 9, from Twelve Concertos in Seven Parts (1742) Largo Allegro Largo Allegro Assai Hornpipe—Andante—Hornpipe JONATHAN SLADE and BETHANNE WALKER, Flute Concertino Program continues on next page Juilliard’s full-scholarship Historical Performance program was established and endowed in 2009 by the generous support of Bruce and Suzie Kovner. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. THOMAS ARNE (1710–78) Concerto No. 5 in G minor from Six Favourite Concertos for the Organ, Harpsichord, or Piano Forte (1793) Largo Allegro spirito Adagio Vivace EUNJI LEE , -

Central Reference CD List

Central Reference CD List January 2017 AUTHOR TITLE McDermott, Lydia Afrikaans Mandela, Nelson, 1918-2013 Nelson Mandela’s favorite African folktales Warnasch, Christopher Easy English [basic English for speakers of all languages] Easy English vocabulary Raifsnider, Barbara Fluent English Williams, Steve Basic German Goulding, Sylvia 15-minute German learn German in just 15 minutes a day Martin, Sigrid-B German [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Dutch in 60 minutes Dutch [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Swedish in 60 minutes Berlitz Danish in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian phrase book & CD McNab, Rosi Basic French Lemoine, Caroline 15-minute French learn French in just 15 minutes a day Campbell, Harry Speak French Di Stefano, Anna Basic Italian Logi, Francesca 15-minute Italian learn Italian in just 15 minutes a day Cisneros, Isabel Latin-American Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Latin American Spanish in 60 minutes Martin, Rosa Maria Basic Spanish Cisneros, Isabel Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Spanish for travelers Spanish for travelers Campbell, Harry Speak Spanish Allen, Maria Fernanda S. Portuguese [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Portuguese in 60 minutes Sharpley, G.D.A. Beginner’s Latin Economides, Athena Collins easy learning Greek Garoufalia, Hara Greek conversation Berlitz Greek in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi travel pack Bhatt, Sunil Kumar Hindi : a complete course for beginners Pendar, Nick Farsi : a complete course for beginners -

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart – Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Piano Concerto No. 20 in D Minor, K. 464 Mozart entered this concerto in his catalog on February 10, 1785, and performed the solo in the premiere the next day in Vienna. The orchestra consists of one flute, two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings. At these concerts, Shai Wosner plays Beethoven’s cadenza in the first movement and his own cadenza in the finale. Performance time is approximately thirty-four minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 20 were given at Orchestra Hall on January 14 and 15, 1916, with Ossip Gabrilowitsch as soloist and Frederick Stock conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on March 15, 16, and 17, 2007, with Mitsuko Uchida conducting from the keyboard. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 6, 1961, with John Browning as soloist and Josef Krips conducting, and most recently on July 8, 2007, with Jonathan Biss as soloist and James Conlon conducting. This is the Mozart piano concerto that Beethoven admired above all others. It’s the only one he played in public (and the only one for which he wrote cadenzas). Throughout the nineteenth century, it was the sole concerto by Mozart that was regularly performed—its demonic power and dark beauty spoke to musicians who had been raised on Beethoven, Chopin, and Liszt. -

The Functions of Harmonic Motives in Schubert's Sonata Forms1 Brian

The Functions of Harmonic Motives in Schubert’s Sonata Forms1 Brian Black Schubert’s sonata forms often seem to be animated by some hidden process that breaks to the surface at significant moments, only to subside again as suddenly and enigmatically as it first appeared. Such intrusions usually highlight a specific harmonic motive—either a single chord or a larger multi-chord cell—each return of which draws in the listener, like a veiled prophecy or the distant recall of a thought from the depths of memory. The effect is summed up by Joseph Kerman in his remarks on the unsettling trill on Gß and its repeated appearances throughout the first movement of the Piano Sonata in Bß major, D. 960: “But the figure does not develop, certainly not in any Beethovenian sense. The passage... is superb, but the figure remains essentially what it was at the beginning: a mysterious, impressive, cryptic, Romantic gesture.”2 The allusive way in which Schubert conjures up recurring harmonic motives stamps his music with the mystery and yearning that are the hallmarks of his style. Yet these motives amount to much more than oracular pronouncements, arising without any apparent cause and disappearing without any tangible effect. Quite the contrary—they are actively involved in the unfolding of the 1 This article is dedicated to William E. Caplin. I would also like to thank two of my colleagues at the University of Lethbridge, Deanna Oye and Edward Jurkowski, for their many helpful suggestions during the article’s preparation. 2 Joseph Kerman “A Romantic Detail in Schubert’s Schwanengesang,” in Walter Frisch (ed.), Schubert: Critical and Analytical Perspectives, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986): 59. -

Music by Handel, Purcell, Corelli & Muffat

Belsize Baroque Director: Persephone Gibbs Soprano: Nia Coleman Music by Handel, Purcell, Corelli & Mufat Sunday 27 November 2016, 6.30 pm St Peter’s, Belsize Square, Belsize Park, London NW3 4HY Programme George Friderick Handel (1685–1759) Concerto Grosso in B flat Op.3 No.1 HWV 312 Allegro – Largo – Allegro The Concerti Grossi Opus 3, drawing together pre-existing works by Handel, were published by the less than scrupulous London publisher John Walsh in 1734. A rival composer, Geminiani, had just taken Walsh to court for printing two sets of his Concerti which he claimed Walsh had acquired illegally. While there is no evidence that Handel objected to Walsh’s selection of his works as Opus 3, it looks as if he did not have a chance to edit them pre-publication; it is for instance odd that the last movement of this B flat concerto is in G Minor. The opening movement has solos for the oboes and a violin, the slow movement adds recorders over an orchestral texture with divided violas, and the final movement features bassoons towards the end: all giving London’s best instrumentalists a chance to shine. George Friderick Handel Two arias from the opera Rinaldo, HWV 7 ‘Augelletti, che cantate’ – ‘Lascia ch’io pianga’ Rinaldo is the first Italian opera Handel composed for London, opening in the Haymarket in February 1711. These two arias are sung by Almirena, the daughter of Godfrey of Bouillon, who is capturing the city of Jerusalem from the infidel during the First Crusade (1096–99). Almirena, a character unknown to Torquato Tasso, from whose epic the plot of the opera is drawn, has been introduced into the plot by the librettist to provide a love interest. -

The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 203 SO 007 735 AUTHOR Pearl, Jesse; Carter, Raymond TITLE Music Listening--The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 42p.; An Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program; SO 007 734-737 are related documents PS PRICE MP-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Aesthetic Education; Course Content; Course Objectives; Curriculum Guides; *Listening Habits; *Music Appreciation; *Music Education; Mucic Techniques; Opera; Secondary Grades; Teaching Techniques; *Vocal Music IDENTIFIERS Classical Period; Instrumental Music; *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT This 9-week, Quinmester course of study is designed to teach the principal types of vocal, instrumental, and operatic compositions of the classical period through listening to the styles of different composers and acquiring recognition of their works, as well as through developing fastidious listening habits. The course is intended for those interested in music history or those who have participated in the performing arts. Course objectives in listening and musicianship are listed. Course content is delineated for use by the instructor according to historical background, musical characteristics, instrumental music, 18th century opera, and contributions of the great masters of the period. Seven units are provided with suggested music for class singing. resources for student and teacher, and suggestions for assessment. (JH) US DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH EDUCATION I MIME NATIONAL INSTITUTE