KATZIE FIRST NATION, and WEST MOBERLY FIRST NATIONS and PROPHET RIVER FIRST NATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shifting Paradigms

SHIFTING PARADIGMS Report of the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage Julie Dabrusin, Chair MAY 2019 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION The proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees are hereby made available to provide greater public access. The parliamentary privilege of the House of Commons to control the publication and broadcast of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees is nonetheless reserved. All copyrights therein are also reserved. Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. -

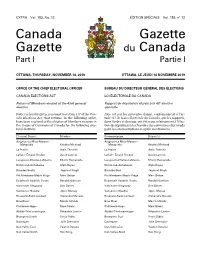

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

Core 1..16 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 42e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 22 No 22 Monday, February 22, 2016 Le lundi 22 février 2016 11:00 a.m. 11 heures PRAYER PRIÈRE GOVERNMENT ORDERS ORDRES ÉMANANT DU GOUVERNEMENT The House resumed consideration of the motion of Mr. Trudeau La Chambre reprend l'étude de la motion de M. Trudeau (Prime Minister), seconded by Mr. LeBlanc (Leader of the (premier ministre), appuyé par M. LeBlanc (leader du Government in the House of Commons), — That the House gouvernement à la Chambre des communes), — Que la Chambre support the government’s decision to broaden, improve, and appuie la décision du gouvernement d’élargir, d’améliorer et de redefine our contribution to the effort to combat ISIL by better redéfinir notre contribution à l’effort pour lutter contre l’EIIL en leveraging Canadian expertise while complementing the work of exploitant mieux l’expertise canadienne, tout en travaillant en our coalition partners to ensure maximum effect, including: complémentarité avec nos partenaires de la coalition afin d’obtenir un effet optimal, y compris : (a) refocusing our military contribution by expanding the a) en recentrant notre contribution militaire, et ce, en advise and assist mission of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in développant la mission de conseil et d’assistance des Forces Iraq, significantly increasing intelligence capabilities in Iraq and armées canadiennes (FAC) en Irak, en augmentant theatre-wide, deploying CAF medical personnel, -

A Parliamentarian's

A Parliamentarian’s Year in Review 2018 Table of Contents 3 Message from Chris Dendys, RESULTS Canada Executive Director 4 Raising Awareness in Parliament 4 World Tuberculosis Day 5 World Immunization Week 5 Global Health Caucus on HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria 6 UN High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis 7 World Polio Day 8 Foodies That Give A Fork 8 The Rush to Flush: World Toilet Day on the Hill 9 World Toilet Day on the Hill Meetings with Tia Bhatia 9 Top Tweet 10 Forging Global Partnerships, Networks and Connections 10 Global Nutrition Leadership 10 G7: 2018 Charlevoix 11 G7: The Whistler Declaration on Unlocking the Power of Adolescent Girls in Sustainable Development 11 Global TB Caucus 12 Parliamentary Delegation 12 Educational Delegation to Kenya 14 Hearing From Canadians 14 Citizen Advocates 18 RESULTS Canada Conference 19 RESULTS Canada Advocacy Day on the Hill 21 Engagement with the Leaders of Tomorrow 22 United Nations High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis 23 Pre-Budget Consultations Message from Chris Dendys, RESULTS Canada Executive Director “RESULTS Canada’s mission is to create the political will to end extreme poverty and we made phenomenal progress this year. A Parliamentarian’s Year in Review with RESULTS Canada is a reminder of all the actions decision makers take to raise their voice on global poverty issues. Thank you to all the Members of Parliament and Senators that continue to advocate for a world where everyone, no matter where they were born, has access to the health, education and the opportunities they need to thrive. “ 3 Raising Awareness in Parliament World Tuberculosis Day World Tuberculosis Day We want to thank MP Ziad Aboultaif, Edmonton MPs Dean Allison, Niagara West, Brenda Shanahan, – Manning, for making a statement in the House, Châteauguay—Lacolle and Senator Mobina Jaffer draw calling on Canada and the world to commit to ending attention to the global tuberculosis epidemic in a co- tuberculosis, the world’s leading infectious killer. -

Safeguarding Canada's National Security

SAFEGUARDING CANADA’S NATIONAL SECURITY WHILE PROTECTING CANADIANS’ PRIVACY RIGHTS: REVIEW OF THE SECURITY OF CANADA INFORMATION SHARING ACT (SCISA) Report of the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics Blaine Calkins Chair MAY 2017 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. For greater certainty, this permission does not affect the prohibition against impeaching or questioning the proceedings of the House of Commons in courts or otherwise. -

Parliamentary Associations' Activities and Expenditures

PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATIONS’ ACTIVITIES AND EXPENDITURES FROM APRIL 1, 2018 TO MARCH 31, 2019 JOINT INTERPARLIAMENTARY COUNCIL REPORT Co-Chairs Hon. Donald Neil Plett, Senator 42nd Parliament, First Session Bruce Stanton, M.P. June 2019 June 2019 JOINT INTERPARLIAMENTARY COUNCIL CO-CHAIRS Hon. Donald Neil Plett, Senator Bruce Stanton, M.P. MEMBERS Hon. Dennis Dawson, Senator Hon. Wayne Easter, P.C., M.P. Hon. Marc Gold, Senator Hon. Mark Holland P.C., M.P. Jenny Kwan, M.P. Scott Simms, M.P. John Brassard, M.P. Linda Lapointe, M.P. CLERK OF THE COUNCIL Colette Labrecque-Riel June 2019 Table of Contents Section I: Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Parliamentary Associations and Interparliamentary Groups ................................................................................ 2 Joint Interparliamentary Council ........................................................................................................................... 4 Supporting Parliamentary Associations ................................................................................................................. 4 Section II: 2018-2019 Activities and Expenditures – Overview ......................................................................... 5 Section III: Activities and Expenditures by Parliamentary Association ............................................................ 12 Canada-Africa Parliamentary Association (CAAF)............................................................................................... -

George Committees Party Appointments P.20 Young P.28 Primer Pp

EXCLUSIVE POLITICAL COVERAGE: NEWS, FEATURES, AND ANALYSIS INSIDE HARPER’S TOOTOO HIRES HOUSE LATE-TERM GEORGE COMMITTEES PARTY APPOINTMENTS P.20 YOUNG P.28 PRIMER PP. 30-31 CENTRAL P.35 TWENTY-SEVENTH YEAR, NO. 1322 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 2016 $5.00 NEWS SENATE REFORM NEWS FINANCE Monsef, LeBlanc LeBlanc backs away from Morneau to reveal this expected to shed week Trudeau’s whipped vote on assisted light on deficit, vision for non- CIBC economist partisan Senate dying bill, but Grit MPs predicts $30-billion BY AbbaS RANA are ‘comfortable,’ call it a BY DEREK ABMA Senators are eagerly waiting to hear this week specific details The federal government is of the Trudeau government’s plan expected to shed more light on for a non-partisan Red Cham- Charter of Rights issue the size of its deficit on Monday, ber from Government House and one prominent economist Leader Dominic LeBlanc and Members of the has predicted it will be at least Democratic Institutions Minister Joint Committee $30-billion—about three times Maryam Monsef. on Physician- what the Liberals promised dur- The appearance of the two Assisted ing the election campaign—due to ministers at the Senate stand- Suicide, lower-than-expected tax revenue ing committee will be the first pictured at from a slow economy and the time the government has pre- a committee need for more fiscal stimulus. sented detailed plans to reform meeting on the “The $10-billion [deficit] was the Senate. Also, this is the first Hill. The Hill the figure that was out there official communication between Times photograph based on the projection that the the House of Commons and the by Jake Wright economy was growing faster Senate on Mr. -

Brampton Mps Host Successful Joint Community BBQ Successful Inaugural Brampton Community BBQ Held by the Brampton Mps

Liberal Electoral District Association Brampton North News Release For Immediate Release Brampton MPs Host Successful Joint Community BBQ Successful Inaugural Brampton Community BBQ Held by the Brampton MPs 28/08/2016 – Brampton, Ontario – The five Federal Liberal Riding Associations for Brampton held an inaugural joint community barbeque on Sunday, August 28th 2016 at the Brampton Soccer Centre. Along with the Brampton Members of Parliament, Kamal Khera (Brampton West), Raj Grewal (Brampton East), Ruby Sahota (Brampton North), Ramesh Sangha (Brampton Centre) and Sonia Sidhu (Brampton South), these Liberal Riding Associations are committed to working together for the betterment of Brampton and Canada. This barbeque was held to provide an opportunity for Bramptonians to meet and speak with their Members of Parliament while enjoying free food, entertainment and activities for the whole family. Also in attendance was Minister Navdeep Bains, MP Iqra Khalid, Mayor Linda Jeffrey, City Councilors Pat Fortini and Gurpreet Dhillon, as well as Peel Region Police, Fire and Paramedic Services. “It is great to see the vibrant community in Brampton come out to celebrate with their Members of Parliament.” said Brampton North’s MP Ruby Sahota. “Kamal, Raj, Sonia, Ramesh and I are working hard for Brampton and we look forward to doing this joint community BBQ on an annual basis.” Great focus is being placed on the collaborative and joint efforts of the five Brampton Members of Parliament as they provide a united voice for Brampton in Ottawa. -30- For media inquiries, please contact: Jashan Singh, Executive Vice-President, Brampton North EDA Email: [email protected] . -

LOBBY MONIT R the 43Rd Parliament: a Guide to Mps’ Personal and Professional Interests Divided by Portfolios

THE LOBBY MONIT R The 43rd Parliament: a guide to MPs’ personal and professional interests divided by portfolios Canada currently has a minority Liberal government, which is composed of 157 Liberal MPs, 121 Conservative MPs, 32 Bloc Québécois MPs, 24 NDP MPs, as well as three Green MPs and one Independent MP. The following lists offer a breakdown of which MPs have backgrounds in the various portfolios on Parliament Hill. This information is based on MPs’ official party biographies and parliamentary committee experience. Compiled by Jesse Cnockaert THE LOBBY The 43rd Parliament: a guide to MPs’ personal and professional interests divided by portfolios MONIT R Agriculture Canadian Heritage Children and Youth Education Sébastien Lemire Caroline Desbiens Kristina Michaud Lenore Zann Louis Plamondon Martin Champoux Yves-François Blanchet Geoff Regan Yves Perron Marilène Gill Gary Anandasangaree Simon Marcil Justin Trudeau Claude DeBellefeuille Julie Dzerowicz Scott Simms Filomena Tassi Sean Casey Lyne Bessette Helena Jaczek Andy Fillmore Gary Anandasangaree Mona Fortier Lawrence MacAulay Darrell Samson Justin Trudeau Harjit Sajjan Wayne Easter Wayne Long Jean-Yves Duclos Mary Ng Pat Finnigan Mélanie Joly Patricia Lattanzio Shaun Chen Marie-Claude Bibeau Yasmin Ratansi Peter Schiefke Kevin Lamoureux Francis Drouin Gary Anandasangaree Mark Holland Lloyd Longfield Soraya Martinez Bardish Chagger Pablo Rodriguez Ahmed Hussen Francis Scarpaleggia Karina Gould Jagdeep Sahota Steven Guilbeault Filomena Tassi Kevin Waugh Richard Lehoux Justin Trudeau -

Parliamentary Associations' Activities and Expenditures

PARLIAMENTARY ASSOCIATIONS’ ACTIVITIES AND EXPENDITURES FROM APRIL 1, 2015 TO MARCH 31, 2016 JOINT INTERPARLIAMENTARY COUNCIL REPORT CO-CHAIRS: HON. FABIAN MANNING, SENATOR BRUCE STANTON, M.P. 41st PARLIAMENT, SECOND SESSION AND 42nd PARLIAMENT, FIRST SESSION October 2016 October 2016 JOINT INTERPARLIAMENTARY COUNCIL CO-CHAIRS Hon. Fabian Manning, Senator Bruce Stanton, M.P. MEMBERS Hon. Percy Downe, Senator Irene Mathyssen, M.P. Hon. Wayne Easter, M.P. Hon. Ginette Petitpas Taylor, M.P. Hon. Andrew Leslie, M.P. Hon. Donald Plett, Senator Dave MacKenzie, M.P. Scott Simms, M.P. CLERK OF THE COUNCIL Colette Labrecque-Riel LIBRARY OF PARLIAMENT Parliamentary Information and Research Service Marcus Pistor, Senior Director October 2016 Table of contents Section I: Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Parliamentary Associations and Interparliamentary Groups ................................................................................ 2 Joint Interparliamentary Council ........................................................................................................................... 3 Supporting Parliamentary Associations ................................................................................................................. 4 Section II: 2015-2016 Activities and Expenditures – Overview......................................................................... 5 Section III: Activities and Expenditures by Parliamentary -

June 25, 2020 Open Letter and Delivered by E-Mail the Right

Canadian Association of Black Lawyers (CABL) 20 Toronto Street Suite 300 Toronto, ON M5C 2B8 Website: cabl.ca Twitter: @CABLNational June 25, 2020 Open Letter and Delivered by E-mail The Right Honourable Justin Trudeau, P.C., M.P. Prime Minister of Canada 80 Wellington Street Ottawa, ON K1A 0A2 The Honourable David Lametti, P.C., Q.C., M.P. Minister of Justice House of Commons Ottawa, ON K1A 0A6 Dear Prime Minister Trudeau and Minister Lametti: Re: Federal Government Strategies to Address Anti-Black Racism Further to my discussion with Minister Lametti, the Canadian Association of Black Lawyers’ (CABL) is keen to collaborate with your Government by offering its insight and expertise on critical issues affecting the Black community. On behalf of CABL, I include a list of strategic priorities we wish you to consider. But first, we want to commend the Minister of Justice for showing a willingness to act. The existence of systemic anti-Black racism in Canadian society, including our legal system, cannot be seriously disputed. Reports from the courts, academia and the media highlight the often- negative experience many Black Canadians experience within the criminal justice system. Black Canadians are stopped, carded and searched by police at disproportionate rates. Similarly, Black Canadians are disproportionately incarcerated. Stated differently, there are too many Black Canadians detained, too many Black Canadians charged and too many Black Canadians in jail. They also make up a disproportionate percentage of the victims of police violence. On the other hand, there is a distinct dearth of diversity among stakeholders of the criminal justice system. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 26, 2017 CITY of BRAMPTON HOSTS

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 26, 2017 CITY OF BRAMPTON HOSTS SUCCESSFUL SIKH HERITAGE MONTH RECEPTION BRAMPTON, ON – This past Tuesday, April 25th, the City of Brampton successfully hosted its 3rd Annual Sikh Heritage Month reception at Brampton City Hall. This year, five outstanding citizens were honoured for their contributions to the community. The reception, which had over 400 attendees, included faith leaders, community groups, dignitaries, and most notably keynote speaker Honourable Minister Amarjeet Sohi. Minister Sohi, who serves as the Minister of Infrastructure and Communities, commended the work of the honourees, as well as the great contributions of the Brampton-Sikh community. “To have the Minister attend the reception was a great honour for us”, said Councillor Gurpreet Dhillon. “The City of Brampton is committed to celebrating its diversity, and today was an excellent example of that.” Councillor Dhillon, who played an integral role in having Sikh Heritage Month recognized on the City’s official calendar in 2015, noted the many different cultures and faiths represented at the event. “Today’s event was attended by people of all backgrounds. When our residents come together to celebrate our diversity, we increase the bonds of our community.” Dignitaries in attendance were Mayor Linda Jeffrey, Councillor Gurpreet Dhillon, Councillor John Sprovieri, Councillor Martin Medeiros, Councillor Gael Miles, Councillor Pat Fortini, Councillor Jeff Bowman, MP Raj Grewal, MP Kamal Khera, MP Deepak Obhrai, MP Ruby Sahota, MP Ramesh Sangha, MP Sonia Sidhu, Minister Amarjeet Sohi, MPP Jagmeet Singh, Bradford Councillor Raj Sandhu, School Trustee Avtar Minhas, and Peel Police Board Chair Amrik Ahluwalia. The following individuals were recognized for their achievements: Avtar Kaur Aujla: The first South Asian City Councillor in Brampton.