Sample Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1St First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern

1st First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern. arr. Ozzie Westley (1944) BPC The Barberpole Cat Program and Song Book. (1987) BB1 Barber Shop Ballads: a Book of Close Harmony. ed. Sigmund Spaeth (1925) BB2 Barber Shop Ballads and How to Sing Them. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1940) CBB Barber Shop Ballads. (Cole's Universal Library; CUL no. 2) arr. Ozzie Westley (1943?) BC Barber Shop Classics ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1946) BH Barber Shop Harmony: a Collection of New and Old Favorites For Male Quartets. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1942) BM1 Barber Shop Memories, No. 1, arr. Hugo Frey (1949) BM2 Barber Shop Memories, No. 2, arr. Hugo Frey (1951) BM3 Barber Shop Memories, No. 3, arr, Hugo Frey (1975) BP1 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 1. (1946) BP2 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 2. (1952) BP Barbershop Potpourri. (1985) BSQU Barber Shop Quartet Unforgettables, John L. Haag (1972) BSF Barber Shop Song Fest Folio. arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1948) BSS Barber Shop Songs and "Swipes." arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1946) BSS2 Barber Shop Souvenirs, for Male Quartets. New York: M. Witmark (1952) BOB The Best of Barbershop. (1986) BBB Bourne Barbershop Blockbusters (1970) BB Bourne Best Barbershop (1970) CH Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle (1936) CHR Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle. Revised (1941) CH1 Close Harmony: Male Quartets, Ballads and Funnies with Barber Shop Chords. arr. George Shackley (1925) CHB "Close Harmony" Ballads, for Male Quartets. (1952) CHS Close Harmony Songs (Sacred-Secular-Spirituals - arr. -

(2016) When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi

When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Random House Publishing Group (2016) http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Copyright © 2016 by Corcovado, Inc. Foreword copyright © 2016 by Abraham Verghese All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. RANDOM HOUSE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kalanithi, Paul, author. Title: When breath becomes air / Paul Kalanithi ; foreword by Abraham Verghese. Description: New York : Random House, 2016. Identifiers: LCCN 2015023815 | ISBN 9780812988406 (hardback) | ISBN 9780812988413 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Kalanithi, Paul—Health. | Lungs—Cancer—Patients—United States—Biography. | Neurosurgeons—Biography. | Husband and wife. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | MEDICAL / General. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Death & Dying. Classification: LCC RC280.L8 K35 2016 | DDC 616.99/424—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015023815 eBook ISBN 9780812988413 randomhousebooks.com Book design by Liz Cosgrove, adapted for eBook Cover design: Rachel Ake v4.1 ep http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Editor's Note Epigraph Foreword by Abraham Verghese Prologue Part I: In Perfect Health I Begin Part II: Cease Not till Death Epilogue by Lucy Kalanithi Dedication Acknowledgments About the Author http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi EVENTS DESCRIBED ARE BASED on Dr. Kalanithi’s memory of real-world situations. However, the names of all patients discussed in this book—if given at all—have been changed. -

11-9-16 Full Paper

The Diocese of Ogdensburg Volume 71, Number 26 INSIDE THIS ISSUE The role of parents in the growth of NORTH COUNTRY vocations I PAGE 11 Advice for parents on screen time for kids I PAG E12 CATHOLIC NOV 9, 2016 All people long for mercy IN SUPPORT VAllCANCITY(CNS)-- Authentic re Buddhist, Sikh and other re The leaders were in Rome a day passes that we do not ligions help people under ligious leaders. for a conference on religions hear of acts of violence, con OF VOCATIONS stand that they are, in fact, "We seek a love that en and mercy organized by the flict, kidnapping, terrorist at loved and can be forgiven dures beyond momentary Pontifical Council for Interre tacks, killings and 'Come Holy and are called to love and pleasures, a safe harbor ligious Dialogue and the In destruction. Spirit, come' forgive others, Pope Francis where we can end our rest ternational Dialogue Center, "It is horrible that at times, said. less wanderings, an infinite which was founded in 2012 to justify such barbarism, "We thirst for mercy, and embrace that forgives and by Saudi Arabia, Austria and the name of a religion or the no technology can quench reconciles," the pope told the Spain with the support of the name of God himself is in that thirst," the pope told leaders Nov. 3 during an au Holy See. voked," Pope Francis told the Jewish, Christian, Muslim, dience at the Vatican. "Sadly," the pope said, "not group. Annual report AT THE BLUE MASS of diocesan Foundation PHOTO BY FR. -

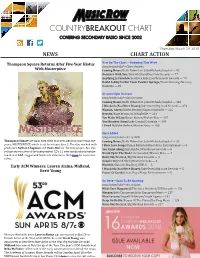

Countrybreakout Chart Covering Secondary Radio Since 2002

COUNTRYBREAKOUT CHART COVERING SECONDARY RADIO SINCE 2002 Thursday, March 29, 2018 NEWS CHART ACTION Thompson Square Returns After Five-Year Hiatus New On The Chart —Debuting This Week song/artist/label—Chart Position With Masterpiece Coming Home/Keith Urban feat. Julia Michaels/Capitol — 45 Nowhere With You/Dave McElroy/Free Flow Records — 77 Anything Is Possible/Southern Halo/Southern Halo Records — 79 David Ashley Parker From Powder Springs/Travis Denning/Mercury Nashville — 80 Greatest Spin Increase song/artist/label—Spin Increase Coming Home/Keith Urban feat. Julia Michaels/Capitol — 468 I Was Jack (You Were Diane)/Jake Owen/Big Loud Records — 372 Woman, Amen/Dierks Bentley/Capitol Nashville — 215 Heaven/Kane Brown/RCA Nashville — 214 You Make It Easy/Jason Aldean/Broken Bow — 207 One Number Away/Luke Combs/Columbia — 199 I Lived It/Blake Shelton/Warner Bros. — 183 Most Added song/artist/label—No. of Adds Thompson Square are back with their irst new album in more than ive Coming Home/Keith Urban feat. Julia Michaels/Capitol — 35 years, MASTERPIECE, which is set for release June 1. The duo worked with I Hate Love Songs/Kelsea Ballerini/Black River Entertainment — 9 producers Nathan Chapman and Dann Huff on the new project, but also You Came Along/Risa Binder/Warehouse Records — 8 self-produced a few of the independent CD’s 11 new tracks which feature Break Up In The End/Cole Swindell/Warner Bros. — 7 touches of R&B, reggae and hard rock in8luences. Click here for a preview Burn Out/Midland/Big Machine Records — 6 video. Keepin' On/Rod Black/Bristol Records — 6 Early ACM Winners: Lauren Alaina, Midland, Worth It/Danielle Bradbery/BMLG — 5 I Was Jack (You Were Diane)/Jake Owen/Big Loud Records — 5 Brett Young Power Of Garth/Lucas Hoge/Forge Entertainment — 5 On Deck—Soon To Be Charting song/artist/label—No. -

Carolina Hurricanes

CAROLINA HURRICANES NEWS CLIPPINGS • August 26, 2021 Durham Bulls honoring Hurricanes with Hockey Night at the DBAP Durham, N.C. — The Durham Bulls will hit the field for an Hurricanes players are expected to attend the game along upcoming home game looking like another one of the with Hurricanes mascot, Stormy! The Hurricanes' warning Triangle's favorite teams. siren will also be at the ballpark. Hockey Night is scheduled for Friday, Sept. 10. at Durham The Bulls are scheduled to take on the Norfolk Tides with a Bulls Athletic Park as the Bulls partner up with their friends at 6:35 p.m. first pitch. The Hurricanes will open the season the Carolina Hurricanes. against the New York Islanders on Thursday, Oct. 14 at PNC Arena. Bulls players and coaches will wear special Carolina Hurricanes-themed jerseys, which will be auctioned off to benefit the Carolina Hurricanes Foundation. Metropolitan Division review: Capitals, Penguins try for another run; Teams on the rise By Adam Gretz Bernier, Tomas Tatar, and Dougie Hamilton. Hamilton is the big addition here and arguably one of the biggest moves of Current Metropolitan Division Favorite: Hurricanes the offseason made by any NHL team. He is one of the top The New York Islanders have been in the Conference overall defensemen in the league. He drives possession at Finals/Semifinals two years in a row, the Pittsburgh Penguins an elite level, produces offense at an elite level, and is a and Washington Capitals still have their cores, and the New better, more impactful defender than he gets credit for being. -

Whathappened

#whathappened Do we trust social media in situations of crisis? Amanda Ehn Master’s thesis Supervisors: Fredrica Nyqvist and Jenny Lindholm Faculty of Education and Welfare Studies Åbo Akademi Vasa, 2018 Abstract Author (Surname, first name) Year Ehn, Amanda 2018 Work title #whathappened – Do we trust social media in situations of crisis? Unpublished thesis for Master’s degree in social policy Pages (total) Vasa: Åbo Akademi. Fakulteten för pedagogik och välfärdsstudier 118 pages Project in which the work was written Project RESCUE Abstract Social media is widely used as a communication channel today, and especially in a crisis, information needs to be correct and reliable; it could mean the difference between life or death. However, social media also has another side; it brings people together after a crisis and gives people an opportunity to show solidarity and love to one another. The aim of this thesis was to examine the relationship between social media usage and trust in situations of crisis, to shed light on the usage of social media in a crisis situation and whether the information retrieved from those platforms is trusted. The thesis describes the theories behind trust, social media, and crisis communication in order to have a base to build the research on. The research focused on three questions: How was SoMe used by people affected by the attack in Stockholm 2017? Do those affected by the attack trust the information on social media? What are the greatest problems with social media in situations of crisis? A single instrumental case study methodology was used to answer these questions, and the study itself was centered around the attack on Drottninggatan in Stockholm the 7th of April 2017. -

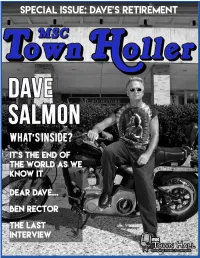

To View Our Fall 2016 Issue of the MSC Town Holler!

It’s the end of the world as we know it By: justin hairston Dave Salmon’s impact as MSC March of 1989. While politics are far Town Hall’s advisor has been inimitable, as from necessary in order to make an any current or former Town Hall member entertaining and engaging concert, it is could tell you. While it is easy to point to still neat that A&M was able to host such recent Town Hall programming highlights a thrilling and topical concert in the heart like Kevin Hart, Twenty One Pilots, and of campus. Ben Rector, Town Hall has had a long list of impressive headliners under Dave’s Though Town Hall will no doubt run as advisor. In fact, back in October of continue to bring in big names and socially 1989, A&M brought rock legends R.E.M. relevant events (in no small part thanks to to G Rollie White, the former home of the Dave’s hard work over the years), it is A&M basketball and volleyball teams. still a huge blow to lose the man who has fearlessly guided Town Hall for decades. R.E.M. formed in 1980, but His impact can be seen in a captivating despite being in the middle of their show like REM, but it can also be seen ascension to worldwide fame in 1989, in the countless stories and memories they gave A&M students a full-force of hundreds of Town Hallers. Dave has performance. The band played a 30 been more than an advisor; he’s been (Thirty!!!) song set, including 3 multi-song a leader, a mentor, and a friend. -

GRAMMY®-Nominated Country Sensation Cam Releases Much-Anticipated New Single, “Diane,” Today!

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 27, 2017 GRAMMY®-Nominated Country Sensation Cam Releases Much-Anticipated New Single, “Diane,” Today! Available for Download and Streaming, “Diane” Was Written and Produced by the Team Behind Cam’s Platinum-Selling #1 Smash, “Burning House,” The Most-Downloaded Song by a Female Country Artist Released Since 2015 Photo credit: Dennis Leupold Download hi-res single artwork and Cam image without type HERE. Nashville, TN – Acclaimed, multi-award-nominated songstress Cam is sure to delight fans anxious for new music as she previews her 2018 Arista Nashville/RCA Records sophomore album with the release of “Diane,” the forthcoming collection’s debut single, available now HERE. Inspired by the storyline of Dolly Parton’s classic “Jolene,” the driving, tempo-rich track delivers a sonically refreshing tale of love and regret and commiseration. The song was co-written by Cam, Jeff Bhasker, and Tyler Johnson, the team behind the most-downloaded song by a female country artist released since 2015—Cam’s Platinum-certified #1 smash, “Burning House”— which propelled Cam to her first GRAMMY®, ACM, CMA, CMT, and American Music Awards nominations. About the song, Cam shares, “‘Diane’ is my response to Dolly Parton’s ‘Jolene.’ It’s the apology so many spouses deserve, but never get. The other woman is coming forward to break the news to the wife about an affair, respecting her enough to have that hard conversation, once she realized he was married. Because everyone should be able to decide their own path in life, based on the truth. Women especially should do this for each other, since our self-worth can still be so wrapped up in our partners. -

Passages Westward

Passages Westward Edited by Maria Lähteenmäki & Hanna Snellman Studia Fennica Ethnologica Artikkelin nimi Studia Fennica Ethnologica 9 1 T F L S (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the elds of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. e rst volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. e subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia Fennica Editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Markku Haakana Pauli Kettunen Leena Kirstinä Teppo Korhonen Johanna Ilmakunnas .. E O SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.nlit. Artikkelin nimi Passages Westward Edited by Maria Lähteenmäki & Hanna Snellman Finnish Literature Society • Helsinki 3 Studia Fennica Ethnologica 9 The publication has undergone a peer review. © 2006 Maria Lähteenmäki, Hanna Snellman and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2006 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB: Tero Salmén ISBN 978-951-858-065-5 (Print) ISBN 978-951-858-067-9 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-858-066-2 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 1235-1954 (Studia Fennica Ethnlogica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sfe.9 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License. -

Television Academy

Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Guest Actor In A Comedy Series For a performer who appears within the current eligibility year with guest star billing. NOTE: VOTE FOR NO MORE THAN SIX achievements in this category that you have seen and feel are worthy of nomination. (More than six votes in this category will void all votes in this category.) Photos, color or black & white, were optional. 001 Jason Alexander as Stanford Kirstie Maddie's Agent Outraged that her co-star is getting jobs, Maddie vows to fire her agent (Jason Alexander). When cowardice stops her from lowering the hammer, she seduces him. Bolstered by her "courage," Arlo, Frank and Thelma face their fears. 002 Anthony Anderson as Sweet Brown Taylor The Soul Man Revelations Boyce slips back into his old habits when he returns to the studio to record a new song. Lolli and Barton step in to keep things running smoothly at the church. Stamps and Kim are conflicted about revealing their relationship. 003 Eric Andre as Deke 2 Broke Girls And The Dumpster Sex When Deke takes Max to his place after a great first date, his “home” is nothing like she expected. Meanwhile, Caroline feels empowered – then scared for her life – after having a shady car towed from the front of their apartment building. 1 Television Academy 2014 Primetime Emmy Awards Ballot Outstanding Guest Actor In A Comedy Series For a performer who appears within the current eligibility year with guest star billing. NOTE: VOTE FOR NO MORE THAN SIX achievements in this category that you have seen and feel are worthy of nomination. -

September 24, 2003 Denson Selected As DMACC President Lacey Dierks Students

Des Moines Area Community College, Boone Campus Volume 3, Issue 2 September 24, 2003 Denson selected as DMACC President Lacey Dierks students. Banner Staff Denson said, “When I meet students in the hallway, I generally ask them two The votes are in and Des Moines Area questions. Number one, are you getting Community College’s new president has your money’s worth? And number two, been announced. are your instructors working you hard Robert Denson, current president of enough? If the answer to either of those Northeast Iowa Community College, questions is ‘No’ when the day is through, was selected as President of DMACC at then we’re not doing our job.” a board meeting on Monday, Sept. 15. In regards to the controversy caused last Board members voted 8-1 in favor of fall by former president David England, choosing Denson, he will begin his duties Denson said, “We must move forward.” on Nov. 1. He plans on working with students and At a press conference on Tuesday businesses in the area to create better mass Denson said that his first day will be partnerships, ultimately benefiting both spent visiting each DMACC campus. He DMACC’s students and the surrounding wants to meet as many students and staff communities. as possible, and hopes to be a visible and Denson knows he has many challenges instrumental figure at each of DMACC’s ahead of him, but he’s willing and excited six campuses. to step up and accept the responsibility. He Denson was nominated as a candidate encourages students to contact him with for the presidential position. -

The Waiting Is the Hardest Part

Student senators- page 4 VOL XIX, NO. 83 the independent student new spaper serv ing notri dam e and saint many's WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 30, 1985 Obud sees an increase in hopefuls for races By MIKE MILLEN Senior Staff Reporter This year’s student body presi dent and vice president race prom ises to yield more candiates than last year, Ombudsman, the overseeing organization for the election, indi cated at last night’s informational meeting. OBUD Election Coordinator The waiting is Maher Mouasher clarified campaign rules at the optional meeting, atten ded by four sets of candidates. About campaign violations, the hardest part Mouasher said, “We will be strict. No violations will pass through un It’s that time of year again, Auditorium. Students waiting in detected and unpunished.” when Notre Dame and Saint Chautauqua Ballroom, passed the Henry Sienkiewicz, OBUD direc Mary's students willingly skip time by playing cards, watching tor, agreed. “We will be classes, and meals, to endure ex television, or even studying. But spot checking ballot boxes, and will treme cold and boredom- all for by the time 4:30 came, chairs had have two people on duty at all times. the chance to come away with a to be passed over the crowd to All endorsements must be verified coveted pair of Keenan Revue separate stampeding students. tickets. Notre Dame’s answer to before they are put up, ” he said, add Second City, the Keenan Revue, The first student to receive 1985 ing, “The penalities are fairly nasty is this weekend, and ticket distri Keenan Revue tickets was John for violations of campaign ex bution was yesterday.