The Pennsylvanian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambrian Ordovician

Open File Report LXXVI the shale is also variously colored. Glauconite is generally abundant in the formation. The Eau Claire A Summary of the Stratigraphy of the increases in thickness southward in the Southern Peninsula of Michigan where it becomes much more Southern Peninsula of Michigan * dolomitic. by: The Dresbach sandstone is a fine to medium grained E. J. Baltrusaites, C. K. Clark, G. V. Cohee, R. P. Grant sandstone with well rounded and angular quartz grains. W. A. Kelly, K. K. Landes, G. D. Lindberg and R. B. Thin beds of argillaceous dolomite may occur locally in Newcombe of the Michigan Geological Society * the sandstone. It is about 100 feet thick in the Southern Peninsula of Michigan but is absent in Northern Indiana. The Franconia sandstone is a fine to medium grained Cambrian glauconitic and dolomitic sandstone. It is from 10 to 20 Cambrian rocks in the Southern Peninsula of Michigan feet thick where present in the Southern Peninsula. consist of sandstone, dolomite, and some shale. These * See last page rocks, Lake Superior sandstone, which are of Upper Cambrian age overlie pre-Cambrian rocks and are The Trempealeau is predominantly a buff to light brown divided into the Jacobsville sandstone overlain by the dolomite with a minor amount of sandy, glauconitic Munising. The Munising sandstone at the north is dolomite and dolomitic shale in the basal part. Zones of divided southward into the following formations in sandy dolomite are in the Trempealeau in addition to the ascending order: Mount Simon, Eau Claire, Dresbach basal part. A small amount of chert may be found in and Franconia sandstones overlain by the Trampealeau various places in the formation. -

Nautiloid Shell Morphology

MEMOIR 13 Nautiloid Shell Morphology By ROUSSEAU H. FLOWER STATEBUREAUOFMINESANDMINERALRESOURCES NEWMEXICOINSTITUTEOFMININGANDTECHNOLOGY CAMPUSSTATION SOCORRO, NEWMEXICO MEMOIR 13 Nautiloid Shell Morphology By ROUSSEAU H. FLOIVER 1964 STATEBUREAUOFMINESANDMINERALRESOURCES NEWMEXICOINSTITUTEOFMININGANDTECHNOLOGY CAMPUSSTATION SOCORRO, NEWMEXICO NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY E. J. Workman, President STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES Alvin J. Thompson, Director THE REGENTS MEMBERS EXOFFICIO THEHONORABLEJACKM.CAMPBELL ................................ Governor of New Mexico LEONARDDELAY() ................................................... Superintendent of Public Instruction APPOINTEDMEMBERS WILLIAM G. ABBOTT ................................ ................................ ............................... Hobbs EUGENE L. COULSON, M.D ................................................................. Socorro THOMASM.CRAMER ................................ ................................ ................... Carlsbad EVA M. LARRAZOLO (Mrs. Paul F.) ................................................. Albuquerque RICHARDM.ZIMMERLY ................................ ................................ ....... Socorro Published February 1 o, 1964 For Sale by the New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources Campus Station, Socorro, N. Mex.—Price $2.50 Contents Page ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION -

Middle Triassic Gastropods from the Besano Formation of Monte San Giorgio, Switzerland Vittorio Pieroni1 and Heinz Furrer2*

Pieroni and Furrer Swiss J Palaeontol (2020) 139:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13358-019-00201-8 Swiss Journal of Palaeontology RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Middle Triassic gastropods from the Besano Formation of Monte San Giorgio, Switzerland Vittorio Pieroni1 and Heinz Furrer2* Abstract For the frst time gastropods from the Besano Formation (Anisian/Ladinian boundary) are documented. The material was collected from three diferent outcrops at Monte San Giorgio (Southern Alps, Ticino, Switzerland). The taxa here described are Worthenia (Humiliworthenia)? af. microstriata, Frederikella cf. cancellata, ?Trachynerita sp., ?Omphalopty- cha sp. 1 and ?Omphaloptycha sp. 2. They represent the best preserved specimens of a larger collection and docu- ment the presence in this formation of the clades Vetigastropoda, Neritimorpha and Caenogastropoda that were widespread on the Alpine Triassic carbonate platforms. True benthic molluscs are very rarely documented in the Besano Formation, which is interpreted as intra-platform basin sediments deposited in usually anoxic condition. Small and juvenile gastropods could have been lived as pseudoplankton attached to foating algae or as free-swimming veliger planktotrophic larval stages. Accumulations of larval specimens suggest unfavorable living conditions with prevailing disturbance in the planktic realm or mass mortality events. However, larger gastropods more probably were washed in with sediments disturbed by slumping and turbidite currents along the basin edge or storm activity across the platform of the time equivalent Middle San Salvatore Dolomite. Keywords: Gastropods, Middle Triassic, Environment, Besano Formation, Southern Alps, Switzerland Introduction environment characterized by anoxic condition in bottom Te Middle Triassic Besano Formation (formerly called waters of an intraplatform basin (Bernasconi 1991; Schatz “Grenzbitumenzone” in most publications) is exposed 2005a). -

A CARBONIFEROUS SYNZIPHOSURINE (XIPHOSURA) from the BEAR GULCH LIMESTONE, MONTANA, USA by RACHEL A

[Palaeontology, Vol. 50, Part 4, 2007, pp. 1013–1019] A CARBONIFEROUS SYNZIPHOSURINE (XIPHOSURA) FROM THE BEAR GULCH LIMESTONE, MONTANA, USA by RACHEL A. MOORE*, SCOTT C. McKENZIE and BRUCE S. LIEBERMAN* *Department of Geology, University of Kansas, 1475 Jayhawk Blvd, Lindley Hall, Room 120, Lawrence, KS 66045-7613, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Geology Department, Room 206B, Zurn Hall of Science, Mercyhurst College, 501 East 38th St., Erie, PA 16546-0001, USA Typescript received 21 November 2005, accepted in revised form 23 August 2006 Abstract: A new synziphosurine, Anderella parva gen. et known locality where synziphosurines occur alongside the sp. nov., extends the known range of this group from the more derived xiphosurids. Xiphosurans reached their great- Silurian to the Carboniferous and is the youngest known so est diversity in the Carboniferous when the xiphosurids far from the fossil record. Previously the youngest synzi- began to occupy brackish and freshwater habitats and phosurine, Kasibelinurus, was from the Devonian of North became dominant over the synziphosurines. The discovery America. Anderella parva has a semi-oval carapace with of the only known Carboniferous synziphosurine in marine pointed genal regions, nine freely articulating opisthosomal sediments may indicate their inability to exploit these same segments and a long styliform tail spine. It is the third xi- environments. phosuran genus to be described from the Bear Gulch Lime- stone and its discovery highlights this deposit as containing Key words: Mississippian, -

Mississippian and Pennsylvanian Fossils of the Albuquerque Country Stuart A

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/12 Mississippian and Pennsylvanian fossils of the Albuquerque country Stuart A. Northrop, 1961, pp. 105-112 in: Albuquerque Country, Northrop, S. A.; [ed.], New Mexico Geological Society 12th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 199 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1961 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

041-2011-Abstracts-BOE-III-Crete.Pdf

Boreskov Institute of Catalysis of the Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk, Russia Institute of Cytology and Genetics of the Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk, Russia Borissiak Paleontological Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia III International Conference “Biosphere Origin and Evolution” RETHYMNO, CRETE, GREECE OCTOBER 16-20, 2011 ABSTRACTS Novosibirsk, 2011 © Boreskov Institute of Catalysis, 2011 INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Alexei Rozanov, Borissiak Paleontological Institute RAS, Moscow, Russia Co‐Chairman Georgii Zavarzin, Institute of Microbiology RAS, Moscow, Russia Co‐Chairman Vadim Agol Moscow State University, Russia Yury Chernov Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Moscow, Russia Institute of Protein Research RAS, Pushchino, Moscow region, Alexander Chetverin Russia David Deamer Biomolecular Engineering, School of Engineering, Santa Cruz, USA V.S. Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy SB RAS, Nikolay Dobretsov Novosibirsk, Russia Mikhail Fedonkin Geological Institute RAS, Moscow, Russia Siegfried Franck Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Germany V.I. Vernadskii Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical Chemistry Eric Galimov RAS, Moscow, Russia Mikhail Grachev Limnological Institute SB RAS, Irkutsk, Russia Richard Hoover Nasa Marshall Space Flight Ctr., Huntsville, USA North‐Western Scientific Center RAS, St. Petersburg State Sergey Inge‐Vechtomov University, Russia Trofimuk Institute of Petroleum‐Gas Geology and Geophysics Alexander Kanygin SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia Astrospace Centre of Lebedev Physical Institute RAS, Moscow, Nikolay Kardashev Russia Józef Kaźmierczak Institute of Paleobiology PAN, Warsaw, Poland Nikolay Kolchanov Institute of Cytology and Genetics SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia Trofimuk Institute of Petroleum‐Gas Geology and Geophysics Alexei Kontorovich SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library Eugene V. -

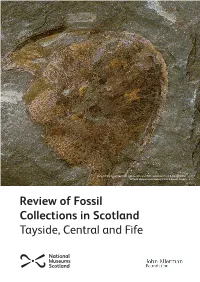

Tayside, Central and Fife Tayside, Central and Fife

Detail of the Lower Devonian jawless, armoured fish Cephalaspis from Balruddery Den. © Perth Museum & Art Gallery, Perth & Kinross Council Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland Tayside, Central and Fife Tayside, Central and Fife Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum Perth Museum and Art Gallery (Culture Perth and Kinross) The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum (Leisure and Culture Dundee) Broughty Castle (Leisure and Culture Dundee) D’Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum and University Herbarium (University of Dundee Museum Collections) Montrose Museum (Angus Alive) Museums of the University of St Andrews Fife Collections Centre (Fife Cultural Trust) St Andrews Museum (Fife Cultural Trust) Kirkcaldy Galleries (Fife Cultural Trust) Falkirk Collections Centre (Falkirk Community Trust) 1 Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum Collection type: Independent Accreditation: 2016 Dumbarton Road, Stirling, FK8 2KR Contact: [email protected] Location of collections The Smith Art Gallery and Museum, formerly known as the Smith Institute, was established at the bequest of artist Thomas Stuart Smith (1815-1869) on land supplied by the Burgh of Stirling. The Institute opened in 1874. Fossils are housed onsite in one of several storerooms. Size of collections 700 fossils. Onsite records The CMS has recently been updated to Adlib (Axiel Collection); all fossils have a basic entry with additional details on MDA cards. Collection highlights 1. Fossils linked to Robert Kidston (1852-1924). 2. Silurian graptolite fossils linked to Professor Henry Alleyne Nicholson (1844-1899). 3. Dura Den fossils linked to Reverend John Anderson (1796-1864). Published information Traquair, R.H. (1900). XXXII.—Report on Fossil Fishes collected by the Geological Survey of Scotland in the Silurian Rocks of the South of Scotland. -

A New Ordovician Arthropod from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa (USA) Reveals the Ground Plan of Eurypterids and Chasmataspidids

Sci Nat (2015) 102: 63 DOI 10.1007/s00114-015-1312-5 ORIGINAL PAPER A new Ordovician arthropod from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa (USA) reveals the ground plan of eurypterids and chasmataspidids James C. Lamsdell1 & Derek E. G. Briggs 1,2 & Huaibao P. Liu3 & Brian J. Witzke4 & Robert M. McKay3 Received: 23 June 2015 /Revised: 1 September 2015 /Accepted: 4 September 2015 /Published online: 21 September 2015 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Abstract Euchelicerates were a major component of xiphosurid horseshoe crabs, and by extension the paraphyly of Palaeozoic faunas, but their basal relationships are uncertain: Xiphosura. The new taxon reveals the ground pattern of it has been suggested that Xiphosura—xiphosurids (horseshoe Dekatriata and provides evidence of character polarity in crabs) and similar Palaeozoic forms, the synziphosurines— chasmataspidids and eurypterids. The Winneshiek may not represent a natural group. Basal euchelicerates are Lagerstätte thus represents an important palaeontological win- rare in the fossil record, however, particularly during the initial dow into early chelicerate evolution. Ordovician radiation of the group. Here, we describe Winneshiekia youngae gen. et sp. nov., a euchelicerate from Keywords Dekatriata . Ground pattern . Microtergite . the Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) Winneshiek Lagerstätte Phylogeny . Synziphosurine . Tagmosis of Iowa, USA. Winneshiekia shares features with both xiphosurans (a large, semicircular carapace and ophthalmic ridges) and dekatriatan euchelicerates such as Introduction chasmataspidids and eurypterids (an opisthosoma of 13 ter- gites). Phylogenetic analysis resolves Winneshiekia at the base Euchelicerates, represented today by xiphosurids (horseshoe of Dekatriata, as sister taxon to a clade comprising crabs) and arachnids (scorpions, spiders, ticks, and their rela- chasmataspidids, eurypterids, arachnids, and Houia. -

THE Geologlcal SURVEY of INDIA Melvioirs

MEMOIRS OF THE GEOLOGlCAL SURVEY OF INDIA MElVIOIRS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA VOLUME XXXVI, PART 3 THE TRIAS OF THE HIMALAYAS. By C. DIENER, PH.0., Professor of Palceontology at the Universz'ty of Vienna Published by order of the Government of India __ ______ _ ____ __ ___ r§'~-CIL04l.~y_, ~ ,.. __ ..::-;:;_·.•,· ' .' ,~P-- - _. - •1~ r_. 1..1-l -. --~ ·~-'. .. ~--- .,,- .'~._. - CALCU'l"l'A: V:/f/ .. -:-~,_'."'' SOLD AT THE Ol<'FICE OF THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY o'U-1kI>i'A,- 27, CHOWRINGHim ROAD LONDON: MESSRS. KEGAN PAUT,, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO. BERLIN : MESSRS. FRIEDLANDEH UND SOHN 1912. CONTENTS. am I• PA.GE, 1.-INTBODUCTION l 11.-LJ'rERA.TURE • • 3· III.-GENERAL DE\'ELOPMEKT OF THE Hrn:ALAYA.K TRIAS 111 A. Himalayan Facies 15 1.-The Lower Trias 15 (a) Spiti . Ip (b) Painkhanda . ·20 (c) Eastern Johar 25 (d) Byans . 26 (e) Kashmir 27 (/) Interregional Correlation of fossiliferous horizons 30 (g) Correlation with the Ceratite beds of the Salt Range 33 (Ti) Correlation with the Lower Trias of Europe, Xorth America and Siberia . 36 (i) The Permo-Triassic boundary . 42 II.-The l\Iiddle Trias. (Muschelkalk and Ladinic stage) 55 (a) The Muschelkalk of Spiti and Painkhanda v5 (b) The Muschelkalk of Kashmir . 67 (c) The llluschelka)k of Eastern Johar 68 (d) The l\Iuschelkalk of Byans 68 (e) The Ladinic stage.of Spiti 71 (f) The Ladinic stage of Painkhanda, Johar and Byans 75 (g) Correl;i.tion "ith the Middle Triassic deposits of Europe and America . 77 III.-The Upper Trias (Carnie, Korie, and Rhretic stages) 85 (a) Classification of the Upper Trias in Spiti and Painkhanda 85 (b) The Carnie stage in Spiti and Painkhanda 86 (c) The Korie and Rhretic stages in Spiti and Painkhanda 94 (d) Interregional correlation and homotaxis of the Upper Triassic deposits of Spiti and Painkhanda with those of Europe and America 108 (e) The Upper Trias of Kashmir and the Pamir 114 A.-Kashmir . -

Ascocerid Cephalopods from the Hirnantian?–Llandovery Stages of the Southern Paraná Basin (Paraguay, South America): first Record from High Paleolatitudes

Journal of Paleontology, page 1 of 11 Copyright © 2018, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/18/0088-0906 doi: 10.1017/jpa.2018.59 Ascocerid cephalopods from the Hirnantian?–Llandovery stages of the southern Paraná Basin (Paraguay, South America): first record from high paleolatitudes M. Cichowolski,1,2 N.J. Uriz,3 M.B. Alfaro,3 and J.C. Galeano Inchausti4 1Universidad de Buenos Aires, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Departamento de Ciencias Geológicas, Área de Paleontología, Ciudad Universitaria, Pab. 2, C1428EGA, Buenos Aires, Argentina 〈[email protected]〉 2CONICET-Universidad de Buenos Aires, Instituto de Estudios Andinos “Don Pablo Groeber” (IDEAN), Buenos Aires, Argentina 3División Geología del Museo de La Plata, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina. 〈[email protected]〉, 〈[email protected]〉 4Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Comunicaciones de Paraguay, Asunción, Paraguay 〈[email protected]〉 Abstract.—Ascocerid cephalopods are described for the first time from high paleolatitudes of Gondwana. Studied material was collected from the Hirnantian?–Llandovery strata of the Eusebio Ayala and Vargas Peña formations, Paraná Basin, southeastern Paraguay. The specimens are poorly preserved and were questionably assigned to the sub- family Probillingsitinae Flower, 1941, being undetermined at genus and species rank because diagnostic characters are not visible. A particular feature seen in our material is the presence of both parts of the ascocerid conch (the juve- nile or cyrtocone and the mature or brevicone) joined together, which is a very rare condition in the known paleonto- logical record. The specimens are interpreted as at a subadult stage of development because fully grown ascocerids would have lost the juvenile shell. -

Cephalopod Reproductive Strategies Derived from Embryonic Shell Size

Biol. Rev. (2017), pp. 000–000. 1 doi: 10.1111/brv.12341 Cephalopod embryonic shells as a tool to reconstruct reproductive strategies in extinct taxa Vladimir Laptikhovsky1,∗, Svetlana Nikolaeva2,3,4 and Mikhail Rogov5 1Fisheries Division, Cefas, Lowestoft, NR33 0HT, U.K. 2Department of Earth Sciences Natural History Museum, London, SW7 5BD, U.K. 3Laboratory of Molluscs Borissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 117997, Russia 4Laboratory of Stratigraphy of Oil and Gas Bearing Reservoirs Kazan Federal University, Kazan, 420000, Russia 5Department of Stratigraphy Geological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 119017, Russia ABSTRACT An exhaustive study of existing data on the relationship between egg size and maximum size of embryonic shells in 42 species of extant cephalopods demonstrated that these values are approximately equal regardless of taxonomy and shell morphology. Egg size is also approximately equal to mantle length of hatchlings in 45 cephalopod species with rudimentary shells. Paired data on the size of the initial chamber versus embryonic shell in 235 species of Ammonoidea, 46 Bactritida, 13 Nautilida, 22 Orthocerida, 8 Tarphycerida, 4 Oncocerida, 1 Belemnoidea, 4 Sepiida and 1 Spirulida demonstrated that, although there is a positive relationship between these parameters in some taxa, initial chamber size cannot be used to predict egg size in extinct cephalopods; the size of the embryonic shell may be more appropriate for this task. The evolution of reproductive strategies in cephalopods in the geological past was marked by an increasing significance of small-egged taxa, as is also seen in simultaneously evolving fish taxa. Key words: embryonic shell, initial chamber, hatchling, egg size, Cephalopoda, Ammonoidea, reproductive strategy, Nautilida, Coleoidea. -

Nautiloidea, Oncocerida) from the Prague Basin

Revision of the Pragian Rutoceratoidea Hyatt, 1884 (Nautiloidea, Oncocerida) from the Prague Basin TÌPÁN MANDA & VOJTÌCH TUREK Superfamily Rutoceratoidea Hyatt, 1884 (Pragian to Frasnian, Devonian) includes nautiloid cephalopods having exogastric cyrtoceracone or coiled shells with periodic walls or raised growth lines (megastriae) forming ridges, some- times modified in various ways into collars, frills, or different outgrowths. High disparity and intraspecific variability of the shell form and sculpture of the rutoceratoids are conspicuous among Early Palaeozoic nautiloids. Consequently, rutoceratoids are divided according to different patterns of growth structures into three families. Parauloceratidae fam. nov. (Pragian to Emsian) contains taxa with cyrtoceracone shells and simple recurrent ribs with ventral sinus. Family Hercoceratidae Hyatt, 1884 (Pragian to Givetian) comprises forms with periodically raised ridges with three lobes form- ing ventrolateral outgrowths during shell growth such as wings, nodes or spines. Family Rutoceratidae Hyatt, 1884 (Pragian to Frasnian) encompases taxa having growth ridges with ventral lobe transforming into undulated frills or dis- tinct periodic collars (megastriae). All of these families had already appeared during early radiation of rutoceratoids in the Pragian. The early radiation of rutoceratoids is, however, adequately recorded only from the Prague Basin. Rutoceratoids become widespread within faunas of Old World and Eastern American realms later during the Emsian and especially Middle Devonian. Three new genera are erected: Parauloceras gen. nov., Otomaroceras gen. nov. and Pseudorutoceras gen. nov. The Pragian Gyroceras annulatum Barrande, 1865 is assigned to the genus Aphyctoceras Zhuravleva, 1974. Rutoceratoids are thus represented by seven genera and eight species in the Pragian Stage of the Prague Basin. In addition, variability of shell coiling among rutoceratoids and its significance for their systematics are discussed.