A Shared Responsibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Fiano

REGIONAL FIANO WINE Regional Fiano VINTAGE 2018 REGION Margaret River VARIETY Fiano ANALYSIS Alcohol 13.5%, pH 3.26, TA 6.7 g/L VINTAGE & WINEMAKING NOTES The 2018 vintage was moderate, mild and a good year to grow Fiano in Margaret River. Rainfall in early January renewed canopies across the region and resulted in beautifully ripe, varietally pure wines that are brimming with perfect, delicate, natural acidity. This select parcel of Margaret River Fiano was harvested in the cool night and transported to Millbrook in the early hours of the morning. The fruit was gently pressed taking only the pure free-run juice, before racking from any solids. Fermentation was carried out at cool temperatures in stainless steel to retain freshness, with a select yeast strain chosen to enhance the varietal expression of this Southern Italian variety. This wine underwent minimal fining and filtration prior to being bottled. TASTING NOTES Colour Brilliant pale lemon. Aroma Lifted lemon, pear and green apple skin with lovely floral, spice and honey notes. Palate A dry, crisp and clean expression of Fiano, showing pear and green apple notes with a twist of fresh lemon zest. Beautifully textural, with good length and an interesting, almost saline edge. CELLARING Enjoy now, lightly chilled. MILLBROOK.WINE | | REGIONAL RANGE The Millbrook Regional range highlights the quality and diversity of Western Australia’s wine regions. Millbrook’s winemakers have identified specific regions best suited to the varieties in the range in order to make expressive, vibrant and varietally pure wines, which perfectly match a range of cuisines. PERTH HILLS Located in the historic town of Jarrahdale in the Perth Hills wine region, Millbrook Winery is PERTH a multi-award winning, boutique vineyard, farm, Jarrahdalrrahd e orchard, restaurant and winery. -

Wooroloo Bushfire Recovery Newsletter July 2021

WOOROLOO BUSHFIRE RECOVERY NEWSLETTER JULY 2021 THE STATE RECOVERY COORDINATION GROUP Contents HAS BEEN ESTABLISHED TO COORDINATE • Introduction 1 EFFORTS TO HELP ALL RESIDENTS AFFECTED BY • Message from the State THE WOOROLOO BUSHFIRE OF FEBRUARY 2021. Recovery Controller 2 • On the ground support 2 Led by State Recovery Controller Dr Ron Edwards and supported by the Department of Fire and Emergency Services, the group includes • Complex clean-up 3 representatives from State Government departments, the City of Swan, the Shire of Mundaring, and not-for-profit groups. The intent of the group is to • Operation woods 3 work together to support fire-affected residents through the recovery process. • Financial assistance 4 Eighty-six homes in the City of Swan and Shire of Mundaring were destroyed in the fire and many more properties were damaged, while essential services • Lesson in recovery 4 were disrupted and social networks affected, leaving many people in need of support. The recovery effort includes the physical clean-up of fire-impacted properties and the removal of rubble, the provision of emergency and ongoing accommodation to residents who have lost their homes and possessions, and the directing of financial relief. It also involves connecting people with other services to help with their physical, mental and emotional wellbeing in the months ahead. All levels of government, not-for-profit groups and the Western Australian community have committed considerable resources to the clean-up and rebuilding effort. The State Recovery Coordination Group will ensure these resources are well-utilised and affected residents get what they need to start the long recovery process. -

Connection Is Dependent on Further Development in the Hills That Is Currently Not Planned

SUBMISSION FROM SALLY BLOCK RE. PETITION No. 54-GIDGEGANNUP URBAN PRECINCT We confirm that we have nottaken our complaint to the Parliamentary Commission for Administrative Investigations. We urge the Committee to investigate this matter further. This development is unique in Western Australia and has the potential to change the nature and amenity of the Perth Hills. There are significant complex issues and a high level of inter-governmental coordination and private sector clarity is necessary. Further enquiry could contribute to this process greatly. The North Eastern Hills Settlement Pattern Plan (NEHSPP) was workshopped over a lengthy period encompassing both the community and Government to ensure that the recommendations would preserve the "Hills Lifestyle". To this end the recommendation was made that three small Townsites would appearthe most appropriate developments in the North Eastern Hills, with total populations in the order of 4000 people. A large townsite was deemed unsuitable given the potential of such a townsite to impact on the "Hills Lifestyle". The Gidgegannup townsite area was just over 200 ha. The proposed area has now expanded to 296.6 ha with a possible second stage to increase the area to 429 ha. The number of lots has been set at 1500 or more dependent on what is needed to fund infrastructure requirements. The impact of the water pipeline to service this proposed development could also have a significant effect on the Hills villages through which it passes in terms of development that is not currently planned. The community does in fact welcome development of our Townsite, justthat it should be appropriate development conforming to our planning documents that have been in place for many years and have had considerable inputfrom the community. -

Eastlink WA Perth to Northam

PROJECT OVERVIEW JUNE 2021 EastLink WA Perth to Northam EastLink WA will transform Perth’s transport network with significant upgrades to Reid and Roe Highways, and an upgraded and new route to Northam. The project is currently in the planning and development phase. Planning and development is underway What is EastLink WA? EastLink WA includes: EastLink WA is a culmination of more than 40 years of • Reid Highway upgrades between Tonkin road planning activities for the north-eastern corridor Highway and Great Northern Highway. of the Perth metropolitan area and Wheatbelt region, comprising several separate projects that have • Roe Highway upgrades between Great undergone different levels of planning and Northern Highway and Clayton Street in development. Bellevue. Together, these projects make up a proposed 80+ • Proposed new section of the Perth Adelaide kilometre stretch of road between Reid Highway and National Highway (PANH) (also referred to as Northam. Once completed, EastLink WA will form the the Orange Route) between Roe Highway / start of the Perth Adelaide National Highway (PANH). Toodyay Road intersection and Great Eastern Highway at the town of Northam. What is happening now? • Provide a safer and more efficient driving The EastLink WA Project is currently in the planning environment from Perth to Northam, through and development phase. bridged intersections and a dual carriageway which will allow road users to travel at a Main Roads has engaged the GHD and BG&E Joint consistent speed. Venture to form the EastLink WA Integrated Project Team (IPT), to undertake the planning studies, design • Provide travel time savings from Perth to refinement and project scoping to produce preliminary Northam of approximately 13 minutes (off designs for the route. -

Spatial Analysis of Climate in Winegrape Growing Regions in Australia

Hall and Jones Climate in winegrape growing regions in Australia 389 Spatial analysis of climate in winegrape-growing regions in Australia_100 389..404 A. HALL1,2 and G.V. JONES3 1 National Wine and Grape Industry Centre, Charles Sturt University,Wagga Wagga, NSW 2678, Australia 2 School of Environmental Sciences, Charles Sturt University, PO Box 789, Albury, NSW 2640, Australia 3 Department of Environmental Studies, Southern Oregon University,Ashland, OR 97520, USA Corresponding author: Dr Andrew Hall, fax +61 2 6051 9897, email [email protected] Abstract Background and Aims: Temperature-based indices are commonly used to indicate long-term suitabil- ity of climate for commercially viable winegrape production of different grapevine cultivars, but their calculation has been inconsistent and often inconsiderate of within-region spatial variability. This paper (i) investigates and quantifies differences between four such indices; and (ii) quantifies the within-region spatial variability for each Australian wine region. Methods and Results: Four commonly used indices describing winegrape growing suitability were calculated for each Australian geographic indication (GI) using temperature data from 1971 to 2000. Within-region spatial variability was determined for each index using a geographic information system. The sets of indices were compared with each other using first- and second-order polynomial regression. Heat-sum temperature indices were strongly related to the simple measure of mean growing season temperature, but variation resulted in some differences between indices. Conclusion: Temperature regime differences between the same region pairs varied depending upon which index was employed. Spatial variability of the climate indices within some regions led to significant overlap with other regions; knowledge of the climate distribution provides a better understanding of the range of cultivar suitability within each region. -

Perth Hills Map 2021

experienceperthhills.com.au 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 GETTING THERE WINERIES, CIDERIES & BREWERIES 1 Dingo Brewery D3 12 Myattsfield Vineyards F4 1 Although covering a vast area, the Perth Hills Region is 2 Malmalling Vineyard C4 13 Fairbrossen Wines F4 2 3 Lion Mill Vineyards D6 14 Tonon Vineyard & Winery F4 Toodyay Rd mostly within a half to one hour drive from the Rd 4 Aldersyde Estate E4 15 Carmel Cider Co. F4 Clenton Perth City. Travelling by car is the easiest way to see and A Walyunga 5 Carldenn Homestead Wines F4 16 CORE Cider House G5 National Park Berry Rd experience this beautiful countryside however let us 6 Ashley Estate Winery F4 17 La Fattoria Perth Hills G5 7 Packing Shed @ Lawnbrook F4 18 Naked Apple Cider H4 F R Berry Bailup Rd share some alternative options! Why not take a day tour Reserve Berry Rd Woondowing 8 Brookside Vineyard F4 19 Roleystone Brewing Co. H4 Nature Reserve and take the driving hassle out of your day? ... especially 9 Hainault Vineyard & Cafe F5 20 King Road Brewery K2 Bailup if your trip involves sampling some locally made wine! 10 Plume Estate Vineyard F4 21 Millbrook Winery L4 Burma Rd Reserve Rd 11 Cosham Wines F4 Burma Rd 3 Hawke Ave If you are planning to self drive, the Perth Hills is GIDGEGANNUP Bailup Rd 1 Werribee Rd teeming with awe inspiring scenic drives. Roads are B HISTORIC PUBS & TAVERNS Rd wide and easy to drive, and Western Australia observes 4 Lilydale 1 Werribee Reen Rd 2 the same driving rules as the rest of Australia; vehicles 1 Noble Falls Tavern B6 8 Sawyers Valley Tavern D6 Rd #helloperth Rd O’Brien Rd 2 The Chidlow Tavern C7 9 Mundaring Weir Hotel E5 Toodyay Rd Wooroloo HWY Kwolyinine travel on the left hand side of the road. -

Perth Hills Mandurah Peel Avon Valley

R O Chidlow L Lake A Zia Park LESCHENAULTIA N Tavern HWY D Leschenaultia ERN SOUTH Equestrian Centre GREAT R Karakamia CONSERVATION D S T Wildlife Sanctuary SWAN VALLEY O N RESERVE CHIDLOW El Caballo Lifestyle Oak Park PERTH HILLS Chalets on E AVON VALLEY N JOHN FORREST V Mount Helena Villages & Resort Reserve 0 5km 10km I Malmalling Vineyard Stoneville L Tavern L NATIONAL PARK E Jarrah Creek B&B Y Gwen’s Retreat R W D H JOHN FORREST MT HELENA EAT EASTERN Forsyth’s Mill GR RD NATIONAL PARK Y PARKERVILLE Lion Mill YA Includes a scenic drive, Swan Hillborne LAKE LESCHENAULTIA D BOLGART O View Tunnel, Eagle View Walk STONEVILLE Cottage This 168-hectare bush land is famous for its terrific TO (WA’s oldest national park) See detailed map SAWYERS canoeing, swimming, cycling and barbecuing Y Railway Reserves Parkerville facilities. Hosts a variety of native tress, wildflowers GOOMALLING W Heritage Trail Tavern VALLEY H Sawyers Valley and Australian wildlife. You can hire canoes, and at Wootra Farm B&B N (40km loop) R Inn Mahogany Grower’s Market the campsite there are showers, a camp kitchen, E H T Creek Country Living Shop powered sites and laundry facilities. OR Hovea Ridge Cottage MUNDARING N N HWY AT STER JULIMAR STRIP GRE GREAT EA MUNDARING KSP Writers’ Centre M Drive along Julimar Road for some U With one third of the Shire’s area classified BEELU NATIONAL PARK N MIDLAND Mundaring DA The Goat Farm RD R as State Forest and a bountiful selection of This park is known for its plethora of recreational Orchard Glory great wineries, restaurants, olive oil T MAS Eco Stay I HO N BELLEVUE G walk and cycle trails, including six of the sites from Fred Jacoby Park, to North Ledge, to Farm Resort producers, pottery studios, homesteads GREENMOUNT Railway Reserves W GLEN and luxury retreats. -

Western Australian Cider Trail Cider Australian Western the About Perth to Denmark to Perth

Tourism WA Tourism the support of support the with Produced the TrailsWA app from the App Store to find more trails to explore. to trails more find to Store App the from app TrailsWA the and organic apple cider vinegar. cider apple organic and realcider.net character of that vintage. that of character download and trailswa.com.au at website WA Trails the Visit Normandy, scrumpy, cider liqueur, apple juice juice apple liqueur, cider scrumpy, Normandy, 649 232 0407 rich in apple flavours and reflecting the the reflecting and flavours apple in rich mountfordwines.com.au and preservative free and include traditional, traditional, include and free preservative and Facebook) and 1345 9776 08 ciders, dry fermented, fully alcohol, high of impact on your palate. All ciders are organic organic are ciders All palate. your on impact website (check 10am–4pm holidays, range unique a a delivers harvest year's Each Fri–Sun, 10am–4pm 10am–4pm Fri–Sun, impact on the environment and a maximum maximum a and environment the on impact Every day during school school during day Every apples. cider Heritage of orchard our from Scotsdale believes in making ciders that have a minimal minimal a have that ciders making in believes 10am–4pm Fri–Mon, made exclusively in a 5 star winery using fruit fruit using winery star 5 a in exclusively made 218 Glenrowan Rd, Rd, Glenrowan 218 WA’s first Cidery in 1987. Tangletoe Cidery Cidery Tangletoe 1987. in Cidery first WA’s Pemberton Naturally fermented European style ciders, ciders, style European fermented Naturally Find us Find from cider UK country Devon and established established and Devon country UK cider from 77 Bamess Rd, Rd, Bamess 77 The Mountford family moved to Pemberton Pemberton to moved family Mountford The Find us Find Unique authentic and traditional cider traditional and authentic Unique It takes two to tangle to two takes It CIDER COMPANY CIDER HERITAGE DENMARK 10. -

Is Lake Leschenaultia a Healthy Lake?

Visit www.perthseasternregion.com.au February/March 2020 Upcoming Dates: Wetland restoration project at Broz Park Clean Up Australia Day— By the Shire of Mundaring March 1 2020 World Water Day— March 22 2020 Earth Hour—March 28 2020 Quick Contacts: City of Kalamunda (08) 9257 9999 Shire of Mundaring (08) 9290 6666 City of Swan (08) 9267 9267 EMRC (08) 9424 2222 Broz Park wetland Let us know if you would like to Photo: Shire of Mundaring receive this newsletter via Late November last year the Shire of Mundaring was successful in our application for fund- email—it’s another way you can ing from the Western Australian Government’s State NRM Program to the value of $26,248 help the environment! over two years for the restoration of the lake at Broz Park, Helena Valley. To register, email the EMRC at Over the last couple of years, it was recognised that reduced rainfall, an increase in the population of water bird species, the feeding of these birds and a large number of feral [email protected] fish, predominately European carp, were all contributing to the poor water quality and with :“Subscribe to Greenpage” occurrence of algal blooms in the lake during the summer months. in the subject heading and your email contact details. For With the newly acquired grant funding and contributions from the Shire of Mundaring, it is further information, please our intention in the first year to undertake the removal of the feral fish, revegetate the water’s edge with 1,200 native sedges and undertake education programs regarding the contact Natasha Jones at the harm that feeding native wildlife can have on the birds and the water they live in. -

Geology, Soils and Climate of the Margaret River Wine Region

Research Library All other publications Research Publications 8-2020 Geology, soils and climate of the Margaret River wine region Peter J. Tille [email protected] Angela Stuart-Street [email protected] Peter S. Gardiner [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchlibrary.agric.wa.gov.au/pubns Part of the Geology Commons, Soil Science Commons, and the Viticulture and Oenology Commons Recommended Citation Tille, P, Stuart-Street, A & Gardiner, P 2020, Geology, soils and climate of the Margaret River wine region, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Perth. This report is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Publications at Research Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in All other publications by an authorized administrator of Research Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Geology, soils and climate of the Margaret River wine region Geology, soils and climate of the Margaret River wine region Peter Tille, Angela Stuart-Street and Peter Gardiner © State of Western Australia (Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development), 2020 Cover: Margaret River winery (photo: DPIRD) Unless otherwise indicated, Geology, soils and climate of the Margaret River wine region by Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australian Licence. This report is available at dpird.wa.gov.au. The Creative Commons licence does not apply to the State Crest or logos of organisations. Recommended reference Tille, P, Stuart-Street, A & Gardiner, P 2020, Geology, soils and climate of the Margaret River wine region, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Perth. -

Attachment 2

1 Contents Background ................................................................................. 2 Executive Summary .................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................. 4 Overview ..................................................................................... 4 Tourism ....................................................................................... 5 Linking to Shire Strategies .......................................................... 6 Linking to Other External Strategies ........................................... 7 Purpose ...................................................................................... 9 Situation Analysis ....................................................................... 9 Economic Value ........................................................................ 13 Tourism Infrastructure and Product .......................................... 13 Summary .................................................................................. 15 Strategic Focus Areas............................................................... 16 Action Plans .............................................................................. 17 Appendix 1 Outcomes of Industry workshop ............................. 18 Appendix 2 Outcomes of Stakeholder meetings ....................... 26 Lake Leschenaultia ................................................................... 26 No.1 Pump Station ................................................................... -

Eastern Railway Deviation HRP Nomination V2

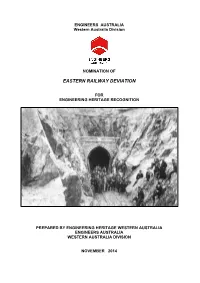

ENGINEERS AUSTRALIA Western Australia Division NOMINATION OF EASTERN RAILWAY DEVIATION FOR ENGINEERING HERITAGE RECOGNITION PREPARED BY ENGINEERING HERITAGE WESTERN AUSTRALIA ENGINEERS AUSTRALIA WESTERN AUSTRALIA DIVISION NOVEMBER 2014 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 3 2. STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE .......................................................................... 4 3. LOCATION .............................................................................................................. 5 4. HERITAGE RECOGNITION NOMINATION FORM ................................................ 7 5. OWNER'S LETTER OF AGREEMENT ................................................................... 8 6. HISTORICAL SUMMARY ....................................................................................... 9 7. BASIC DATA ......................................................................................................... 18 8. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION AND CURRENT CONDITION ................................... 19 9. ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE .................................................................... 29 10. EMINENT PERSONS ASSOCIATED WITH THE PROJECT …………………..... 30 11. INTERPRETATION PLAN AND BUDGET ........................................................... 34 12. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................... 35 13. REFERENCES ....................................................................................................