Overwatch As a Shared Universe: Game Worlds in a Transmedial Franchise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

MATTHEW REILLY UNIVERSE a Jumpchain CYOA

MATTHEW REILLY UNIVERSE A Jumpchain CYOA Welcome to the shared universe of Matthew Reilly’s novels. You, visitor, are at the tip of the spear. This world of high stakes, nail-biting action needs heroes like you, now more than ever, to defend its people from forces that would seek to control it for their own ends. To explain a little more about the world you’ve stumbled into, to the vast bulk of humanity the world is quite mundane; your average citizen has as roughly the same concept of their world as you or I, and it would be quite easy to live your life as though nothing was any different. Yet behind the curtain, many wheels are in motion. Intelligence organisations and Special Forces units clash in exotic locations – Antarctic research labs, overgrown ruins, secret military facilities – often where highly unusual discoveries are made and where the most daring come away with the prize. Heavily-armed bounty hunters and Private Military Corporations chase lucrative contracts across the world for money and glory; careless of international law and often any collateral damage. In uncharted wilds, hidden cultures and tribes who have never been exposed to the modern world protect secrets from the forgotten past and carry out the rites of their forefathers to this day. Shadowy groups steer the courses of governments with hidden hands. Conspiracies of hate and enlightenment both grow inky webs throughout the military-industrial complex and permeate universities, corporations, the government and other institutions. And behind even these secret manipulators lie great mysteries which continue to shape the world as we know it after many thousands of years, and which may spell its doom...or its salvation. -

The Cw Arrowverse and Myth-Making, Or the Commodification of Transmedia Franchising

PRODUCTIONS / MARKETS / STRATEGIES THE CW ARROWVERSE AND MYTH-MAKING, OR THE COMMODIFICATION OF TRANSMEDIA FRANCHISING CHARLES JOSEPH Name Charles Joseph Arrowverse, a shared narrative space based on DC-inspired Academic centre University of Rennes 2 original series which provided the network with a fertile E-mail address [email protected] groundwork to build upon. The CW did not hesitate to capitalize on its not-so-newfound superhero brand to KEYWORDS induce a circulation of myth, relying on these larger-than- The CW; DC comics; Arrowverse; transmedia; convergence; life characters at the heart of American pop culture to superhero; myth. fortify its cultural and historical bedrock and earn its seat along the rest of the Big 4. This paper aims to decipher how The CW pioneered new technology-based tools ABSTRACT which ultimately changed the American media-industrial The CW’s influence over the American network television landscape of the early 2010s, putting these tools to the landscape has never ceased to grow since its creation test with the network’s superhero series. It will thus also in 2006. The network’s audience composition reflects address how the Arrowverse set of characters has triggered The CW’s strategies to improve its original content as cross-media and transmedia experimentations, how The well as diversifying it, moving away from its image as a CW stimulated rapport with its strong fan base, as well network for teenage girls. One of the key elements which as how the network has been able to capitalize on the has supported this shift was the development of the superhero genre’s evocative capacities. -

Valiant Entertainment and Sony Pictures Today Announced a Deal To

Valiant Entertainment and Sony Pictures today announced a deal to bring two of Valiant's award-winning comic book superhero franchises— BLOODSHOT and HARBINGER—to the big screen over the course of five feature films that will culminate in the shared universe crossover film, HARBINGER WARS. BLOODSHOT, arriving in theaters in 2017, will kick off the five-picture plan leading to HARBINGER WARS and will be directed by David Leitch & Chad Stahelski (John Wick) from a script by Jeff Wadlow (Kick Ass 2) and Eric Heisserer (Story of Your Life). Neal H. Moritz and Toby Jaffe fromOriginal Film (The Fast and the Furious franchise) and Dinesh Shamdasani from Valiant Entertainment will produce the film. Matthew Vaughn and Jason Kothari will serve as executive producers. HARBINGER will follow shortly thereafter from a script by Eric Heisserer (Story of Your Life). Sony and Valiant remain tight-lipped about potential directors. Neal H. Moritz and Toby Jaffe from Original Film(The Fast and the Furious franchise) and Dinesh Shamdasani from Valiant Entertainment will produce. Both BLOODSHOT and HARBINGER will be followed by sequels before the title characters confront each other head on in HARBINGER WARS—a motion picture directly inspired by Valiant’s critically acclaimed 2013 comic book crossover of the same name. Andrea Giannetti will oversee the five- picture HARBINGER WARS initiative for Sony Pictures. “Valiant is one of the most successful publishers in the history of comics, and Neal is one of the best action producers in the business today. This is a formidable partnership that will bring two incredibly commercial franchises with global appeal together on the big screen,” said Sony Entertainment Motion Picture Group President Doug Belgrad. -

The Expanded 'Verse

The Expanded 'Verse: Serialized Transmediality in Firefly/Serenity ............ by Frederick Blichert, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario Submitted August 2014 © 2014, Frederick Blichert ii We know now that a text is not a line of words releasing a single "theological" meaning (the "message" of the Author- God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. Roland Barthes1 iii ABSTRACT Popular narratives often extend textual content across multiple media platforms, creating transmedia stories. Recent scholarship has stressed the permeability of "the text," suggesting that the framework of a text, made up of paratexts including trailers and DVD extras, must be included in textual analysis. Here, I propose that this notion may be productively coupled with a theory of seriality––we may frame this phenomenon in the filmic terms of a narrative being comprised of transmedia sequels and/or prequels, or in the televisual language of episodes in a series. Through a textual analysis of the multifaceted transmedia narrative Firefly (2002-2003), I argue for a theoretical framework that further destabilizes the traditional text by considering such paratextual works as comic books, web videos, and the feature film Serenity (Joss Whedon, 2005) as narrative continuations within a single metatext that eschews the centrality of any one text over the others in favour of seriality. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Erika Balsom, Malini Guha, André Loiselle, and Charles O'Brien for their notes on various versions, drafts, and proposals of this material, along with Sylvie Jasen and Murray Leeder, who encouraged me to workshop some of these ideas as guest lecturer in their undergraduate courses. -

TM & ©© 20166 Geg Nius Brands S Inninini Tetteteternnrnrnr

TM & © 2016 GeG nius Brands InIntet1ernrnaattioionaal,l, Incnc. All ririghghttss resserrvev d. From a history-making, cross-generational superhero creative dynamic duo responsible for some of the highest profile and most successful superhero franchises... STAN LEE Fabian Nicieza Comic industry living legend Co-creator and writer of the who created Spider-Man, biggest sleeper superhero The Hulk, Fantastic Four, Iron hit of 2016, Deadpool, which Man, Thor, X-Men, and many broke numerous box office other fictional characters and records and became the introduced a shared universe highest-grossing R-rated into superhero comic books. film of all time, the highest In 2016, he was celebrated grossing X-Men film and a for 75 years in the industry. sequel has already been greenlit. 2 Together, they are the guiding creative forces behind one of the most innovative and captivating new adult-oriented comic superhero franchises... STAN LEE’S COSMIC CRUSADERS. 3 THE SHOW STAN LEE’S COSMIC CRUSADERS is a caustic and inflammatory exploration into the nature of heroism and the challenges facing immigrants in an age of 24/7 media coverage, Kardashians as role models, and society’s general need for daily outrage. • Adventure, comedy, satire and social criticism are doled out in equal measure. • A superhero show that is not about super heroics, but about the burden of being superheroes. • A workplace comedy and a satire of the basic tropes of the superhero genre. • Shameless enough to have its cake and eat it too, so expect lots of superhero action even as superheroes are being lampooned! 4 LO, THERE SHALL BE HEROES! (But for now, we get these guys.) It began, as so many stories do, with WRITER’S BLOCK. -

TV Remakes, Revivals, Updates, and Continuations: Making Sense of the Reboot on Television

Représentations dans le monde anglophone – Janvier 2017 TV Remakes, Revivals, Updates, and Continuations: Making Sense of the Reboot on Television Mehdi Achouche, Université Lyon 3 Jean Moulin Keywords: reboot, remake, reimagining, update, TV series Mots-clés : reboot, remake, réinterprétation, adaptation, série télévisée When discussing the remake, it is generally the case that we are talking about the movie remake. Stigmatized or (more rarely) defended, the remake is historically thought of as a cinematographic institution, with very little thought devoted so far to the television remake1. Yet the phenomenon has been dramatically increasing over the past few years. A zap2it.com article counted in late 2013 32 projects being either remakes or spinoffs, with another 52 series being based on books or comics, accounting for 20% of the shows in development at the five broadcast networks for the 2014-15 season. By comparison, 53 such projects were developed throughout the previous season2. While TV series have been said to be in a new golden age thanks to their “cinematisation”, they thus allegedly are in danger, according to the same article, echoing the long-standing complaints about “recycling” on the big screen, of ironically falling victim to the “movie-fication” of the business: “TV development is starting to look an awful lot like the movie business, where at the big- studio level pre-sold franchises and risk aversion seem to be the guiding principles.” Or, as another writer puts it more succinctly, “there’s a point where the recycled material is just garbage”3. 1 Only two book-length studies entirely dedicated to the TV remake exist so far, edited by the same scholars: Lavigne Carlen, Marvotich Heather (eds.), American Remakes of British Television: Transformations and Mistranslations, Lenham: Lexington Books, 2011; and Lavigne, Carlen (ed.), Remake Television: Reboot Re-use Recycle. -

What Makes the Foundation Seem So Realistic? How Is T

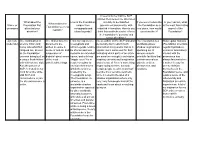

It seems to me that the SCP articles themselves are structured What about the How is the Foundation similarly to declassified If you were to describe In your opinion, what What makes the Name or Foundation first unique from government documents, with the Foundation as a is the most fascinating Foundation seem so username attracted your creepypasta and redacted information. How do you real place, how would aspect of the realistic? attention? urban legends? think this aesthetic choice effects you describe it? Foundation? the Foundation's 'persona' and sense of realism? Zyn (site The combination of The clinical tone the From my experience, I'm an author on the SCP wiki and I The Foundation is a How regular humans moderator) science fiction and documents are creepypasta and personally don't redact much worldwide-power (Foundation scientists, horror was what first written in evoke a urban legends tend to information in my works, but as a shadow organization regular bystanders, intrigued me, as well sense of realism and be shorter and less stylistic tool it works well for both operating out of victims of anomalies) as the Foundation suspension of rooted in an extended indicating which parts of an article various esoteric interact with the universe being built on disbelief about some canon, and with less are sensitive enough to be hidden, scientific facilities that anomalous has a unique flash-fiction- of the most "wiggle room" for a inspiring curiosity and imagination contain anomalous always fascinated me. with-clinical-tone style. unbelievable things. reader or author to and a sense of "there's something objects, entities, It makes it easy for Also the picture of envision themselves bigger going on here, but only phenomena, and one to envision SCP-173 stuck in my within the universe certain people need to know that". -

Super Heroes V Scorsese: a Marxist Reading of Alienation and the Political Unconscious in Blockbuster Superhero Film

Kutztown University Research Commons at Kutztown University Kutztown University Masters Theses Spring 5-10-2020 SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM David Eltz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/masterstheses Part of the Film Production Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Eltz, David, "SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM" (2020). Kutztown University Masters Theses. 1. https://research.library.kutztown.edu/masterstheses/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Research Commons at Kutztown University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kutztown University Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Research Commons at Kutztown University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Kutztown University of Pennsylvania Kutztown, Pennsylvania In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English by David J. Eltz October, 2020 Approval Page Approved: (Date) (Adviser) (Date) (Chair, Department of English) (Date) (Dean, Graduate Studies) Abstract As superhero blockbusters continue to dominate the theatrical landscape, critical detractors of the genre have grown in number and authority. The most influential among them, Martin Scorsese, has been quoted as referring to Marvel films as “theme parks” rather than “cinema” (his own term for auteur film). -

Transmedial Universes Charting the Heuristics of Media Constellations

TRANSMEDIAL UNIVERSES CHARTING THE HEURISTICS OF MEDIA CONSTELLATIONS Sjors Martens Sjors Martens Transmedial Universes Charting the Heuristics of Media Constellations Master thesis Sjors Martens 3614824 RMA Media and Performance Studies Supervisors: Dr.M.J. Kattenbelt Prof. Dr. Joost Raessens Cover by Wouter Martens. Character design by Ubisoft. © 2015 by Sjors Martens All rights reserved Contents Figure Credits v Abstract vii Acknowledgements viii Introduction: Gazing upon the Stars The Discovery of a Universal Trend 1 1 Connecting the Dots The Playful Ontology of Media Constellations 13 What in the World? – Formative Universe Characteristics 15 The Ontology of Sicartian Play 22 Playing the Universe – Interrelations of Universe Characteristics 27 2 To Infinity and Beyond Additive Comprehension in and Beyond ASSASSIN’S CREED 31 Comprehension Revisited 33 “I have so many questions” – Canalised Additive Comprehension 37 Parallel Worlds - Problematizing Additive Comprehension 50 3 Colossal Cosmic Powers Agency in Transmedial Universes 57 The Mantles of Worldly Agency 59 Killing by the Book – Agency in the IP Universe 62 Collective Creation: Curated and Negotiated Universes 73 Conclusion - The Edge of the Universe Finding that Proper Restaurant 85 Works Cited 91 iii iv Figure Credits Fig. 1 (p.1): “Assassin’s Creed II Third Person Ending.” Assassin’s Creed II. Ubisoft Montreal. 2015. Author’s Screenshot. Fig. 2 (p.1): “Assassin’s Creed II Direct Address.” Assassin’s Creed II. Ubisoft Montreal. 2015. Author’s Screenshot. Fig. 3 (p.38): Ubisoft Montreal. “Apple of Eden.” Assassin’s Creed Wiki. 21st April 2013. Screenshot. Accessed 27th July 2015. Fig. 4 (p.39): Kerschl, Karl, Cameron Stewart, and Nadine Thomas. -

You're Listening to Imaginary Worlds, a Show About How We Create Them

1 You’re listening to Imaginary Worlds, a show about how we create them and why we suspend our disbelief. I’m Eric Molinsky. This year is going to be epic. Three massively huge sci-fi fantasy franchises are going to come to a conclusion. On April 14th, Game of Thrones will air its final season – which is six episodes -- but they are going to be six massive, 90-minute episodes that have taken years to make. I can’t even imagine the budget. CLIP: GAME OF THRONES TRAILER On April 26th, Avengers: Endgame comes out, which is the sequel to last year’s giant crossover movie Infinity War, and it’s reportedly going to be the end of the line for the original Avengers team after 20-something movies. CLIP: AVENGERS ENDGAME TRAILER And in December, Star Wars Episode IX will conclude the new trilogy, and the entire Skywalker saga that began in 1977. But the thing that I’m really excited about is the fact that so many characters – heroic characters -- are going to wrap up their stories. I can’t wait to find out -- are they going to die? If they do, is it going to be a heroic death, or is their death going feel unfair and need to be avenged? If they survive, will they get endings that allow them to live on in our collective imagination – or in other media? Or are we going to be disappointed? Are we going to spend months hashing out why their endings were a big let down? And throughout all of this, I keep thinking about The Hero’s Journey – and by that I mean the idea of the concept of The Hero’s Journey, as it was first introduced by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 non-fiction book, “The Hero With a Thousand Faces.” Joseph Campbell was a professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College from the 1930s to the 1970s. -

Transfictionality, Thetic Space, and Doctrinal Transtexts: the Procedural Expansion of Gor in Second Li

Duret, Christophe. "Transfictionality, Thetic Space, and Doctrinal Transtexts: The Procedural Expansion of Gor in Second Life’s Gorean Role-playing Games." Intermedia Games—Games Inter Media: Video Games and Intermediality. Ed. Michael Fuchs and Jeff Thoss. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. 249–270. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501330520.ch-012>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 18:51 UTC. Copyright © Michael Fuchs, Jeff Thoss and Contributors 2019. You may share this work for non- commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 12 Transfictionality, Thetic Space, and Doctrinal Transtexts: The Procedural Expansion of Gor in Second Life ’s Gorean Role- playing Games Christophe Duret maginary worlds created through a multitude of works in different media I have become a mainstay in contemporary popular culture. 1 Those works are linked together by a relation called “transfi ctionality,” a phenomenon “by which two or more texts, whether from the same author or not, jointly relate to the same fi ction, either by repetition of characters, extension of a prior plot or sharing of a fi ctional universe.” 2 The Assassin’s Creed franchise, for example, represents a transfi ction based on several media, which, in their combination, make up a transmedia story (a transfi ctional story told through many texts belonging to many media). In this franchise, twenty-two games contribute to a shared universe, along with twenty- eight comics, three animated short fi lms, a movie, eight novels, and an encyclopedia.