Understanding Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vote:555 Wakiso District Quarter2

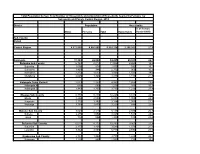

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:555 Wakiso District Quarter2 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 2 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:555 Wakiso District for FY 2018/19. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Accounting Officer, Wakiso District Date: 23/01/2019 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:555 Wakiso District Quarter2 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 1,866,456 2,935,943 157% Discretionary Government Transfers 9,904,329 5,214,920 53% Conditional Government Transfers 49,420,127 26,067,150 53% Other Government Transfers 6,781,008 3,386,269 50% Donor Funding 1,582,182 485,303 31% Total Revenues shares 69,554,103 38,089,585 55% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Planning 490,348 354,418 330,744 72% 67% 93% Internal Audit 140,357 71,796 59,573 51% 42% 83% Administration 8,578,046 6,260,718 5,539,808 73% 65% 88% Finance 1,133,250 730,592 652,040 64% 58% 89% Statutory Bodies 1,346,111 724,322 650,500 54% 48% 90% Production -

Local Government Councils' Performance and Public Service

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFORMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA Wakiso District Council Score-Card Report 2011/2012 Susan Namara - Wamanga Martin Kikambuse Ssali Peninah Kansiime ACODE Public Service Delivery and Accountability Report Series No.3, 2013 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCILS’ PERFORMANCE AND PUBLIC SERVICE DELIVERY IN UGANDA Wakiso District Council Score-Card Report 2011/2012 Susan Namara - Wamanga Martin Kikambuse Ssali Peninah Kansiime ACODE Public Service Delivery and Accountability Report Series No.3, 2013 Published by ACODE P. O. Box 29836, Kampala Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Namara-Wamanga, S., et.al., (2013). Local Government Councils’ Performance and Public Service Delivery in Uganda: Wakiso District Council Score-Card Report 2011/12. ACODE Public Service Delivery and Accountability Report Series No.3, 2013. Kampala. © ACODE 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations and grants from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purposes or for purposes of informing public policy is excluded from this restriction. ISBN 978-9970-07-022-0 Wakiso District Council Score-Card Report 2011/12 Wakiso District Council Score-Card -

Wakiso DLG.Pdf

Local Government Performance Contract FY 2016/17 Vote: 555 Wakiso District Structure of Performance Contract PART A: PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS OF ACCOUNTING OFFICERS PART B: SUMMARY OF DEPARTMENT PERFORMANCE AND WORKPLANS Pursuant to the Public Financial Management Act of 2015, Part VII – Accounting and Audit, Section 45 (3), the Accounting Officer shall enter into an annual budget performance contract with the Permanent Secretary/Secretary to the Treasury. The performance contract consists of two parts – Part A and Part B. Part A outlines the core performance requirements against which my performance as an Accounting Officer will be assessed, in two areas: 1. Budgeting, Financial Management and Accountability, which are common for all Votes; and 2. Achieving Results in five Priority Programmes and Projects identified for the specific Vote I understand that Central Government Accounting Officers will communicate their 5 priorities of the vote within three months of the start of the Financial Year and the priorities for local governments will be established centrally. Part B sets out the key results that a Vote plans to achieve in 2016/17. These take the form of summaries of Ministerial Policy Statement (MPS) for central government AOs and budget narrative summaries for Local government AOs. I hereby undertake, as the Accounting Officer, to achieve the performance requirements set out in Part A of this performance contract and to deliver on the outputs and activities specified in the work plan of the Vote for FY 2016/17 subject to the availability of budgeted resources set out in Part B. I, as the Accounting Officer, shall be responsible and personally accountable to Parliament for the activities of this Vote. -

LG Budget Estimates 201213 Wakiso.Pdf

Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 555 Wakiso District Structure of Budget Estimates A: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures B: Detailed Estimates of Revenue C: Detailed Estimates of Expenditure D: Status of Arrears Page 1 Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 555 Wakiso District A: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Revenue Performance and Plans 2011/12 2012/13 Approved Budget Receipts by End Approved Budget June UShs 000's 1. Locally Raised Revenues 3,737,767 3,177,703 7,413,823 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 5,373,311 4,952,624 5,648,166 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 28,713,079 27,512,936 32,601,298 2c. Other Government Transfers 6,853,215 4,532,570 10,697,450 3. Local Development Grant 1,757,586 1,949,046 1,756,183 Total Revenues 46,434,958 42,124,880 58,116,921 Expenditure Performance and Plans 2011/12 2012/13 Approved Budget Actual Approved Budget Expenditure by UShs 000's end of June 1a Administration 1,427,411 1,331,440 3,894,714 1b Multi-sectoral Transfers to LLGs 5,459,820 4,818,229 0 2 Finance 679,520 658,550 2,623,938 3 Statutory Bodies 1,017,337 885,126 1,981,617 4 Production and Marketing 3,060,260 3,015,477 3,522,157 5 Health 4,877,837 4,807,510 6,201,655 6 Education 21,144,765 19,753,179 24,948,712 7a Roads and Engineering 6,161,280 4,538,877 11,151,699 7b Water 802,836 631,193 1,063,321 8 Natural Resources 427,251 238,655 659,113 9 Community Based Services 610,472 678,202 1,175,071 10 Planning 630,334 302,574 560,032 11 Internal Audit 135,835 117,414 334,893 Grand Total 46,434,958 41,776,425 58,116,922 Wage Rec't: 22,456,951 21,702,872 24,924,778 Non Wage Rec't: 16,062,717 13,930,979 23,191,011 Domestic Dev't 7,915,291 6,142,574 10,001,133 Donor Dev't 0 0 0 Page 2 Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 555 Wakiso District B: Detailed Estimates of Revenue 2011/12 2012/13 Approved Budget Receipts by End Approved Budget of June UShs 000's 1. -

Population by Parish

Total Population by Sex, Total Number of Households and proportion of Households headed by Females by Subcounty and Parish, Central Region, 2014 District Population Households % of Female Males Females Total Households Headed HHS Sub-County Parish Central Region 4,672,658 4,856,580 9,529,238 2,298,942 27.5 Kalangala 31,349 22,944 54,293 20,041 22.7 Bujumba Sub County 6,743 4,813 11,556 4,453 19.3 Bujumba 1,096 874 1,970 592 19.1 Bunyama 1,428 944 2,372 962 16.2 Bwendero 2,214 1,627 3,841 1,586 19.0 Mulabana 2,005 1,368 3,373 1,313 21.9 Kalangala Town Council 2,623 2,357 4,980 1,604 29.4 Kalangala A 680 590 1,270 385 35.8 Kalangala B 1,943 1,767 3,710 1,219 27.4 Mugoye Sub County 6,777 5,447 12,224 3,811 23.9 Bbeta 3,246 2,585 5,831 1,909 24.9 Kagulube 1,772 1,392 3,164 1,003 23.3 Kayunga 1,759 1,470 3,229 899 22.6 Bubeke Sub County 3,023 2,110 5,133 2,036 26.7 Bubeke 2,275 1,554 3,829 1,518 28.0 Jaana 748 556 1,304 518 23.0 Bufumira Sub County 6,019 4,273 10,292 3,967 22.8 Bufumira 2,177 1,404 3,581 1,373 21.4 Lulamba 3,842 2,869 6,711 2,594 23.5 Kyamuswa Sub County 2,733 1,998 4,731 1,820 20.3 Buwanga 1,226 865 2,091 770 19.5 Buzingo 1,507 1,133 2,640 1,050 20.9 Maziga Sub County 3,431 1,946 5,377 2,350 20.8 Buggala 2,190 1,228 3,418 1,484 21.4 Butulume 1,241 718 1,959 866 19.9 Kampala District 712,762 794,318 1,507,080 414,406 30.3 Central Division 37,435 37,733 75,168 23,142 32.7 Bukesa 4,326 4,711 9,037 2,809 37.0 Civic Centre 224 151 375 161 14.9 Industrial Area 383 262 645 259 13.9 Kagugube 2,983 3,246 6,229 2,608 42.7 Kamwokya -

The Uganda Gazette, General Notice No. 425 of 2021

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCIL ELECTIONS, 2021 SCHEDULE OF ELECTION RESULTS FOR DISTRICT/CITY DIRECTLY ELECTED COUNCILLORS DISTRICT CONSTITUENCY ELECTORAL AREA SURNAME OTHER NAME PARTY VOTES STATUS ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABIM KIYINGI OBIA BENARD INDEPENDENT 693 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABIM OMWONY ISAAC INNOCENT NRM 662 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABIM TOWN COUNCIL OKELLO GODFREY NRM 1,093 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABIM TOWN COUNCIL OWINY GORDON OBIN FDC 328 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABUK TOWN COUNCIL OGWANG JOHN MIKE INDEPENDENT 31 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABUK TOWN COUNCIL OKAWA KAKAS MOSES INDEPENDENT 14 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABUK TOWN COUNCIL OTOKE EMMANUEL GEORGE NRM 338 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ALEREK OKECH GODFREY NRM Unopposed ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ALEREK TOWN COUNCIL OWINY PAUL ARTHUR NRM Unopposed ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ATUNGA ABALLA BENARD NRM 564 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ATUNGA OKECH RICHARD INDEPENDENT 994 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY AWACH ODYEK SIMON PETER INDEPENDENT 458 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY AWACH OKELLO JOHN BOSCO NRM 1,237 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY CAMKOK ALOYO BEATRICE GLADIES NRM 163 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY CAMKOK OBANGAKENE POPE PAUL INDEPENDENT 15 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY KIRU TOWN COUNCIL ABURA CHARLES PHILIPS NRM 823 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY KIRU TOWN COUNCIL OCHIENG JOSEPH ANYING UPC 404 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY LOTUKEI OBUA TOM INDEPENDENT 146 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY LOTUKEI OGWANG GODWIN NRM 182 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY LOTUKEI OKELLO BISMARCK INNOCENT INDEPENDENT 356 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY MAGAMAGA OTHII CHARLES GORDON NRM Unopposed ABIM LABWOR COUNTY MORULEM OKELLO GEORGE ROBERT NRM 755 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY MORULEM OKELLO MUKASA -

Thesis.Pdf (1.512Mb)

Thesis for doctoral degree (Ph.D) 2008 ADOLESCENT MOTHERHOOD IN UGANDA Dilemmas, Health Seeking Behaviour and Coping Responses Lynn Muhimbuura Atuyambe MAKERERE UNIVERSITY Kampala and Stockholm 2008 From the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda and the Department of Public Health Sciences, Division of International Health (IHCAR), Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden ADOLESCENT MOTHERHOOD IN UGANDA Dilemmas, Health Seeking Behaviour and Coping Responses Lynn Muhimbuura Atuyambe MAKERERE UNIVERSITY Kampala and Stockholm 2008 The cover pictures were taken from the study district (Wakiso). They illustrate the studies‘ context, the research process, as well as the importance of the need for an improved road network so as to improve access to health facilities. All previously published papers were reproduced with permission from the publisher. Published by Karolinska Institutet and Makerere University. Printed by US-AB © Lynn M Atuyambe, 2008 ISBN: 978-91-7409-212-7 To My dear wife Harriet, the children Lisa-Maria and Leon-Faustine, and Our dear Parents ABSTRACT Introduction: Maternal mortality remains one of the most daunting public health problems in resource limited settings. Maternal health services play a critical role in the improvement of sexual and reproductive health and rights, especially for adolescent mothers. Adolescence is a time of rapid change and transition that can be stressful and difficult; pregnancy can further complicate this period. In Uganda, morbidity and mortality among adolescent mothers and their children are high. In order to better understand this situation, studies (I-IV) were conducted with the following objectives: to describe experiences and problems of pregnant adolescents (I); to describe health seeking behaviour (II) and analyze coping responses (III) of adolescents during pregnancy, delivery and early motherhood; and to compare health seeking practices of adolescents and adult mothers during pregnancy and early motherhood (IV). -

(Ursb): Notice to the Public on Marriage Registration

NOTICE TO THE PUBLIC ON MARRIAGE REGISTRATION Uganda Registration Services Bureau (URSB) wishes to inform the general public that all marriages conducted in Uganda MUST be filed with the Registrar of Marriages. The public is reminded that only church marriages conducted in Licensed and Gazetted places of worship are registrable and it is the duty of the licensed churches to file a record of the celebrated marriages with the Registrar of Marriages by the 10th day of every month, the marriages conducted under the Islamic Faith and the Hindu faith must be registered within three months from the date of the marriage and the Customary marriages must be registered at the Sub-County or Town council where the marriage took place within six months from the date of the marriage. Wilful failure to register marriages celebrated by the Marriage Celebrants violates the provisions of the Marriage Act and criminal proceedings may be instituted against them for failure to perform their statutory duties. The Bureau takes this opportunity to appreciate all Marriage Celebrants who are compliant. The public is hereby informed of the compliance status of Faith Based Organizations as at January 2021. MERCY K. KAINOBWISHO REGISTRAR GENERAL BORN AGAIN CHURCHES ELIM PENTECOSTAL CHURCH 01/30/2020 KYABAKUZA FULLGOSPEL CHURCH MASAKA 01/06/2020 PEARL HAVEN CHRISTIAN CENTER CHURCH 03/03/2020 UNITED CHRISTIAN CENTRE-MUKONO 11/19/2019 FAITH BASED ORGANIZATION DATE OF ELIM PENTECOSTAL CHURCH KAMPALA 08/27/2020 KYAMULIBWA WORSHIP CENTRE 09/11/2018 PEARL HEAVEN CHRISTIAN -

For the Year Ended 30Th June 2017

` OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF WAKISO DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2017 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACROYNMS ........................................................................................................ iii Key Audit Matter ............................................................................................................... 5 Utilization of Medicines and Medical Supplies...................................................... 5 Stock outs of Medicines and Health Supplies ...................................................... 6 Expired Drugs ............................................................................................................ 6 Under Staffing ............................................................................................................ 7 Emphasis of Matter........................................................................................................... 7 Unpaid Pension Arrears ............................................................................................ 7 Other Matter ...................................................................................................................... 8 Failure to Implement Budget as approved by Parliament .................................. 8 Low Recovery of Youth Livelihood Program Funds ............................................ 8 Mismanagement of Designated Areas ................................................................... -

Vote: 555 Wakiso District Structure of Budget Estimates - PART ONE

Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 555 Wakiso District Structure of Budget Estimates - PART ONE A: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures B: Detailed Estimates of Revenue C: Detailed Estimates of Expenditure D: Status of Arrears Page 1 Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 555 Wakiso District A: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Revenue Performance and Plans 2012/13 2013/14 Approved Budget Receipts by End Approved Budget June UShs 000's 1. Locally Raised Revenues 2,144,169 1,791,635 3,239,245 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 3,059,586 2,970,715 2,942,599 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 32,601,298 31,996,803 36,235,037 2c. Other Government Transfers 10,299,801 4,724,322 4,865,053 3. Local Development Grant 962,178 652,142 991,290 4. Donor Funding 0 795,158 Total Revenues 49,067,033 42,135,617 49,068,381 Expenditure Performance and Plans 2012/13 2013/14 Approved Budget Actual Approved Budget Expenditure by UShs 000's end of June 1a Administration 1,673,530 1,422,732 1,658,273 2 Finance 876,480 826,781 981,379 3 Statutory Bodies 996,706 786,619 1,242,096 4 Production and Marketing 3,314,816 3,219,151 3,191,107 5 Health 5,350,708 5,126,200 6,580,574 6 Education 24,488,156 23,891,768 27,393,555 7a Roads and Engineering 9,464,392 3,891,931 4,560,385 7b Water 1,007,375 652,692 972,899 8 Natural Resources 467,285 286,132 615,856 9 Community Based Services 848,277 724,202 712,587 10 Planning 409,569 422,709 983,878 11 Internal Audit 169,739 107,085 175,793 Page 2 Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 555 Wakiso District 2012/13 2013/14 Approved Budget Actual Approved Budget Expenditure by UShs 000's end of June Grand Total 49,067,033 41,358,002 49,068,381 Wage Rec't: 24,004,735 23,918,051 27,484,152 Non Wage Rec't: 16,069,523 11,035,117 12,068,153 Domestic Dev't 8,992,775 6,404,834 8,720,918 Donor Dev't 0 0 795,158 Page 3 Local Government Budget Estimates Vote: 555 Wakiso District B: Detailed Estimates of Revenue 2012/13 2013/14 UShs 000's Approved Budget Receipts by End Approved Budget of June 1. -

SERVICE PLAN ASSESSMENT REPORT Abridged Version

SERVICE PLAN ASSESSMENT REPORT Abridged Version Bus Rapid Transit-KCCA/GKMA June 2020 CIG Uganda is funded with UK Aid and implemented by Cardno International Development This work is a product of the staff of the Cities and Infrastructure for Growth Uganda, a UK Government funded programme implemented by Cardno International Development in Uganda. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO), Cardno International Development or its Board of Governors of the governments they represent. Cardno International Development does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. Rights and Permissions Cardno. Cardno International Development encourages printing or copying information exclusively for personal and non- commercial use with proper acknowledgment of source. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works for commercial purposes without the express, written consent of Cardno International Development of their CIG Uganda office. Any queries should be addressed to the Publisher, CIG Uganda, Plot 31 Kanjokya Street, 3rd Floor, Wildlife Tower, Uganda Kampala or Cardno International Development, Level 5 Clarendon Business Centre, 42 Upper Berkley Street, Marylebone, London, W1H5PW UK. Cover photos: CIG Uganda Table of Contents List of Tables i List of Figures iii List of Acronyms iv EXECUTIVE -

Covid-19 Vaccination Sites by District In

COVID-19 VACCINATION SITES BY DISTRICT IN UGANDA Serial Number District/Division Service point Abim hospital Alerek HCIII 1 Abim Marulem HCIII Nyakwae HCIII Orwamuge HCIII Adjumani Hospital Dzaipi HCII 2 Adjumani Mungula HC IV Pakele HCIII Ukusijoni HC III Kalongo Hospital Lirakato HC III 3 Agago Lirapalwo HCIII Patongo HC III Wol HC III Abako HCIII Alebtong HCIV 4 Alebtong Amogo HCIII Apala HCIII Omoro HCIII Amolatar HC IV Aputi HCIII 5 Amolatar Etam HCIII Namasale HCIII Amai Hosp Amudat General Hospital Kalita HCIV 6 Amudat Loroo HCIII Cheptapoyo HC II Alakas HC II Abarilela HCIII Amuria general hospital 7 Amuria Morungatuny HCIII Orungo HCIII Wera HCIII Atiak HC IV Kaladima HC III 8 Amuru Labobngogali HC III Otwee HC III Pabo HC III Akokoro HCIII Apac Hospital 9 Apac Apoi HCIII Ibuje HCIII Page 1 of 16 COVID-19 VACCINATION SITES BY DISTRICT IN UGANDA Serial Number District/Division Service point Teboke HCIII AJIA HCIII Bondo HCIII 10 Arua Logiri HCIII Kuluva Hosp Vurra HCIII Iki-Iki HC III Kamonkoli HC III 11 Budaka Lyama HC III Budaka HC IV Kerekerene HCIII Bududa Hospital Bukalasi HCIII 12 Bududa Bukilokolo HC III Bulucheke HCIII Bushika HC III Bugiri Hospital BULESA HC III 13 Bugiri MUTERERE HC III NABUKALU HC III NANKOMA HC IV BUSEMBATYA HCIII BUSESA HC IV 14 Bugweri IGOMBE HC III LUBIRA HCIII MAKUUTU HC III Bihanga HC III Burere HC III 15 Buhweju Karungu HC III Nganju HC III Nsiika HC IV Buikwe HC III Kawolo Hospital 16 Buikwe Njeru HCIII Nkokonjeru Hospital Wakisi HC III Bukedea HC IV Kabarwa HCIII 17 Bukedea Kachumbala HCIII