Connecticut Wildlife Nov/Dec 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON 23(3) 461-466.Pdf

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 23: 461–466, 2012 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society FIRST DESCRIPTION OF THE NEST AND EGGS OF THE PLAIN-FLANKED RAIL (RALLUS WETMOREI) Adriana Rodríguez-Ferraro1,2, Eugenia Sánchez2, & Miguel Lentino3 1Departamento de Estudios Ambientales, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Apdo. 89.000, Caracas 1080-A, Venezuela. E-mail: [email protected] 2Laboratorio de Ecología Molecular de Vertebrados, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Apdo. 89.000, Caracas 1080-A, Venezuela. 3Fundación William H. Phelps, Apdo. 2009, Caracas 1010-A, Venezuela. Primera descripción del nido y los huevos de la Polla de Wetmore (Rallus wetmorei). Key words: Plain-flanked Rail, Rallus wetmorei, eggs, mangrove, nest, Venezuela. INTRODUCTION conservation priorities in Venezuela (Rodrí- guez et al. 2004). Main threats for this rail The Plain-flanked Rail (Rallus wetmorei) is a are the loss and deterioration of mangrove Venezuelan endemic species deserving urgent habitat as a consequence of expanding attention from a conservation perspective. touristic developments and activities derived This bird was first described in the mid-1940s from petrochemical industries (Rodríguez & (Zimmer & Phelps 1944), and after a few Rojas-Suárez 2008). These problems even other observations during the following 10 exist within the boundaries of the few pro- years, it went unrecorded for almost three tected areas (three national parks and one decades, until rediscovered in 1999 (Hilty wildlife refuge) where the species is known to 2003). It is restricted to a small area along the occur. central coast of Venezuela where it is known Recovery efforts of endangered birds from eight localities (Taylor 1996), but in have been hampered by the lack of basic recent years, it has been found in only five of knowledge on their biology, thus, research these sites (Rodríguez-Ferraro & Lentino in focused on determining biological character- prep.). -

Recovery Strategy for the King Rail (Rallus Elegans) in Canada

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the King Rail (Rallus elegans) in Canada King Rail 2010 Recommended citation: Environment Canada. 2010. Recovery Strategy for the King Rail (Rallus elegans) in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vi + 21 pp. For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including COSEWIC Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk Public Registry (www.sararegistry.gc.ca). Cover illustration: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement du Râle élégant (Rallus elegans) au Canada [Proposition] » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment, 2010. All rights reserved. ISBN Catalogue no. Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. Recovery Strategy for the King Rail 2010 PREFACE The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years. The Minister of the Environment and the Minister responsible for the Parks Canada Agency are the competent ministers for the recovery of the King Rail and have prepared this strategy, as per section 37 of SARA. -

King Rail (Rallus Elegans) in Canada

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the King Rail Rallus elegans in Canada ENDANGERED 2000 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION DES ENDANGERED WILDLIFE ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: Please note: Persons wishing to cite data in the report should refer to the report (and cite the author(s)); persons wishing to cite the COSEWIC status will refer to the assessment (and cite COSEWIC). A production note will be provided if additional information on the status report history is required. COSEWIC 2000. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the King Rail Rallus elegans in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 10 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) James, R.D. 2000. Update COSEWIC status report on the King Rail Rallus elegans in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the King Rail Rallus elegans in Canada Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-10 pp. Previous Report: Page, A.M. 1994. Update COSEWIC status report on the King Rail Rallus elegans in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 24 pp. Cosens, S.E. 1985. COSEWIC status report on the King Rail Rallus elegans in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 64 pp. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Rapport du COSEPAC sur la situation du Râle élégant (Rallus elegans) au Canada – Mise à jour Cover illustration: King Rail — illustration by Ross D. -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

Priority Species for South Carolina State Comprehensive Wildlife

Priority Species* for the South Carolina State Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Plan Revised October 18, 2004 To satisfy Required Element 1, we had to create a priority species list. To arrive at this list, taxa experts were consulted who took into consideration the following criteria: state or federal status/rank, feasibility of South Carolina making a difference to the conservation of the species, population status (if known), distribution in the state, limiting factors affecting the species, the degree of exploitation/harvest, and the severity of threats faced by the species. Based upon professional judgment and scientific literature, species were scored and some were added or deleted to the list during the process. In the end, a list of species, most in need of management, was formed. What follows is that list. Please remember that this is a DRAFT, meaning that species are still under review in some categories. Check back often for updates. *Species (including insects, marine fish, and marine invertebrates) will be added or deleted as new information becomes available. MAMMALS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LANDBIRD GROUP Clethrionomys gapperi Southern red-backed vole SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Condylura cristata Star-nosed mole Corynorhinus rafinesquii Rafinesque's big-eared bat Elanoides forficatus Swallow-tailed kite Lasiurus intermedius Northern yellow bat Haliaeetus leucocephalus Bald eagle Microtus pennsylvanicus Meadow vole Falco peregrinus Peregrine falcon Myotis austroriparius -

Rapid Ecological Assessment for the Wildlife and State Natural Areas of the Southern Kettle Moraine Region

Rapid Ecological Assessment for the Wildlife and State Natural Areas of the Southern Kettle Moraine Region A Rapid Ecological Assessment Focusing on Rare Plants, Selected Rare Animals, and High-quality Natural Communities Properties included in this report are: Big Muskego Lake Wildlife Area New Munster Wildlife Area Cherry Lake Sedge Meadow State Natural Area Tichigan Wildlife Area Honey Creek Wildlife Area Turtle Creek Wildlife Area Lulu Lake State Natural Area Turtle Valley Wildlife Area New Munster Bog Island State Natural Area Vernon Wildlife Area Wisconsin’s Natural Heritage Inventory Program Bureau of Endangered Resources Department of Natural Resources P.O. Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707 May 2011 PUB ER-829 2011 Acknowledgments We extend our appreciation to Brian Glenzinski, property manager at Big Muskego Wildlife Area, Turtle Creek Wildlife Area, Turtle Valley Wildlife Area, and Vernon Wildlife Area; Marty Johnson, property manager at Honey Creek Wildlife Area, New Munster Wildlife Area, and Tichigan Wildlife Area; Paul Sandgren, natural area manager at Lulu Lake State Natural Area; and Jerry Ziegler and Eric Howe (The Nature Conservancy) for their support and assistance. Primary Authors: Christina Isenring and Ryan O’Connor Contributors: Craig Anderson – botany, rare plants, report editing Julie Bleser – data management Susan Borkin – lepidopteran surveys Owen Boyle – community ecology Andy Clark – botany Jeff Dare – herpetology Dawn Hinebaugh – report editing, data processing Randy Hoffman – report editing -

Marsh Bird Guild

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2010-2015 Marsh Birds Guild American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps American Coot Fulica americana Purple Gallinule Porphyrula martinica Black Rail Laterallus jamaicensis Sedge Wren Cistothorus platensis Clapper Rail Rallus longirostris Sora Porzana carolina Common Gallinule Gallinula galeata Yellow Rail Coturnicops noveboracensis King Rail Rallus elegans Virginia Rail Rallus limicola Least Bittern Ixobrychus exilis Wilson’s Snipe Gallinago delicata NOTE: The Black Rail is described in more detail in a separate species account. The Wilson’s Snipe is also referenced in the Migratory Shorebirds Guild. Contributor (2005): John E. Cely Reviewed and Edited (2012): Craig Watson (USFWS); (2013) Lisa Smith and Christy Hand (SCDNR) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Descriptions The members of the Marsh Birds Guild vary widely in appearance and size. The rails and bitterns have long, slender beaks and stilt-like legs for wading while the coot and grebe have shorter legs with webbed feet for paddling. Sizes for the species vary from the large American Bittern at 58 cm (23 in.) to the small Sedge Wren at 11 cm (4.5 in.). The most colorful of the group is the Purple Gallinule. The male has plumage in shades of green, purple, and blue with bright American Bittern photo by BLM yellow feet and long toes (Sauer et al. 2000). The Black Rail is the smallest North American rail measuring 10-15 cm (4 -6 in.) in length and 35 g (1.2 oz.) in weight (Eddleman et al. 1994). Adult rails have strikingly red irises, a dark gray to blackish head, gray neck and breast, rufous nape, and a black and white patterned back. -

Checklist of Species Within the CCBNEP Study Area: References, Habitats, Distribution, and Abundance

Current Status and Historical Trends of the Estuarine Living Resources within the Corpus Christi Bay National Estuary Program Study Area Volume 4 of 4 Checklist of Species Within the CCBNEP Study Area: References, Habitats, Distribution, and Abundance Corpus Christi Bay National Estuary Program CCBNEP-06D • January 1996 This project has been funded in part by the United States Environmental Protection Agency under assistance agreement #CE-9963-01-2 to the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission. The contents of this document do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Environmental Protection Agency or the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission, nor do the contents of this document necessarily constitute the views or policy of the Corpus Christi Bay National Estuary Program Management Conference or its members. The information presented is intended to provide background information, including the professional opinion of the authors, for the Management Conference deliberations while drafting official policy in the Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP). The mention of trade names or commercial products does not in any way constitute an endorsement or recommendation for use. Volume 4 Checklist of Species within Corpus Christi Bay National Estuary Program Study Area: References, Habitats, Distribution, and Abundance John W. Tunnell, Jr. and Sandra A. Alvarado, Editors Center for Coastal Studies Texas A&M University - Corpus Christi 6300 Ocean Dr. Corpus Christi, Texas 78412 Current Status and Historical Trends of Estuarine Living Resources of the Corpus Christi Bay National Estuary Program Study Area January 1996 Policy Committee Commissioner John Baker Ms. Jane Saginaw Policy Committee Chair Policy Committee Vice-Chair Texas Natural Resource Regional Administrator, EPA Region 6 Conservation Commission Mr. -

2010 Box Score

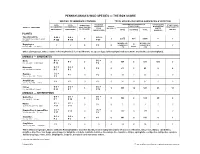

PENNSYLVANIA’S WILD SPECIES — THE BOX SCORE SPECIES* OF IMMEDIATE CONCERN TOTAL SPECIES (INCLUDING SUBSPECIES & VARIETIES) PRESUMED REPRODUCING CURRENTLY IN NON-BREEDING PABS- PABS- DOWNLISTED PENNSYLVANIA EXTIRPATED EXTINCT PENNSYLVANIA MIGRANTS OR GROUP OF ORGANISMS RECOMMENDED RECOMMENDED SINCE 1990 DUE RESPONSIBILITY FROM (GLOBALLY) WINTER † † TO RECOVERY ‡ ENDANGERED THREATENED PENNSYLVANIA NATIVE NONNATIVE TOTAL RESIDENTS SPECIES PLANTS Vascular plants G 24 + G 4 + G 10 + Rev. May 2010 — B. Isaac, S. Grund 0 2 2,075 931 3,006 — ? & T. Block P 300 P 115 P 97 MOSSES ~350 0 MOSSES ~350 Bryophytes ? ? 0 P 3 0 LIVERWORTS LIVERWORTS — ? Rev. Sep. 2007 — J. Lendemer ~150 known ~150 Other plant groups, whose status in Pennsylvania is less well known, are green algae (Chlorophyta) and stoneworts or pondweeds (Charophyta). ANIMALS — CHORDATES G 1 + G 2 + Birds P 3 2 2 184 5 189 196 9 Rev. June 2010 — M. Brittingham P 14 P 4 G 1 + G 2 + Mammals 1 P 9 0 63 3 65 0 4 Rev. June 2010 — M. Gannon P 3 P 1 G 2 + Reptiles P 1 0 P 2 0 35 1 36 0 7 To be rev. Aug. 2010 — T. Maret P 2 Amphibians P 4 P 1 0 P 1 0 37 0 37 0 3 To be rev. Aug. 2010 — T. Maret G 5 + G 2 + G 2 + Fishes 6 1 165 18 183 26 13 Rev. June 2010 — R. Criswell P 23 P 7 P 14 ANIMALS — ARTHROPODS G 4 + G 1 + G 1 + Butterflies 0 0 122 2 124 20 2 Rev. July 2010 — B. -

Xvi. List of Common and Scientific Names

XVI. LIST OF COMMON AND SCIENTIFIC NAMES Listed below are the scientific and common names of all species identified in the text. The scientific name is usually provided (parenthetically) at the first usage of the common name; subsequently, the common name alone is used throughout the text. Scientific names are presented in taxonomic groupings to the Order, except for the Monera and Fungi, which are presented only by Phylum. Within Order, scientific names are presented alphabetically. The taxonomies were obtained from the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (U.S. Department of Agriculture et al., 2005), the National Plant Data Center (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2005), the National Biological Information Infrastructure (U.S. Geological Survey, 2006), and the Systema Naturae 2000 (Brands, 2005). KINGDOM MONERA Phylum Bacteria Vibrio cholera Cholera bacterium KINGDOM FUNGI Phylum Ascomycota Cryphonectria parasitica Chestnut-blight fungus Fusarium oxysporum Fusarium (wilt) fungus Phylum Oomycota Phytophthora cinnamomi Cinnamon fungus Phylum Imperfecti Verticillium spp. Verticillium (wilt) fungus species KINGDOM PLANTAE Division Bryophyta Class Sphagnopsida Order Sphagnales Sphagnum spp. Bog moss species Division Pteridophyta Class Filicopsida Order Polypodiales Onoclea sensibilis Sensitive fern Division Coniferophyta Class Pinopsida Order Pinales Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic white-cedar Larix laricina Tamarack Piceamariana Blackspruce 409 Order Taxales Taxus brevifolia Pacific yew Division Magnoliophyta Class Liliopsida Order Cyperales Carex pseudocyperus Cypress-like sedge Carexspp. Sedge species Cyperusspp. Sedge species Distichlis spicata Spikegrass Eleocharis parvula Dwarf spike rush Panicum spp. Panic grass species Phragmites australis Common reed Scirpus maritimus Saltmarsh bulrush Scirpus robustus Stout bulrush Spartina alterniflora Smooth cordgrass Spartina patens Salt-marsh hay Spartina spp. Cordgrass species Zea mays Corn Order Najadales Potamogeton spp. -

King Rail (Rallus Elegans)

King Rail (Rallus elegans) Pennsylvania Endangered Bird Species State Rank: S1B (critically imperiled), Global Rank: G4 (apparently secure) Identification The king rail is so named because of its large size and bright coloration. This plump chicken-sized bird is a bright rusty color. They range in size from 15 to 19 inches in height and have 21- to 25-inch wingspans. Males are larger than females. Bills are long, slightly decurved and yellow with brown tips. These birds are extremely secretive and would rather run than fly to escape detection. They are rarely seen, therefore, and are most often located by their loud calls, a resonant grunting bup- bup, bup, bup, bup, more rapid at the end. Biology-Natural History King rail nests are platforms up to 9 inches in diameter, 6 to Photo Credit: Rob Criswell 18 inches above the water. They are built of grasses, sedges and cattails in shallow water marshes and roadside ditches. From 6 to 15 pale, slightly spotted brown eggs are laid in a shallow depression of the nest. Overhead cover is often pulled over the nest. Young are able to fly about 60 days after hatching. Wading in shallow water, king rails feed on crustaceans, small fish, frogs and insects. In winter, food items consist of grains - particularly rice - and berries. North American State/Province Conservation Status Habitat Map by NatureServe (August 2007) This rail lives in freshwater and brackish marshes and roadside ditches in eastern North America, primarily along the Atlantic coast. It is a very rare breeder in the few larger State/Province marshes remaining in Pennsylvania. -

King Rail Endangered in Iowa Rallus Elegans Introduction the King Rail Is a Chicken-Sized Marsh Bird and the Largest of the Rails Found in the U.S

IOWA AUDUBON IOWA IBA EDUCATION INITIATIVE PART 4: SPECIES ACCOUNTS STATUS: ENDANGERED King Rail Endangered in Iowa Rallus elegans Introduction The King Rail is a chicken-sized marsh bird and the largest of the rails found in the U.S. This species is a rare migrant and summer breeder in Iowa, and is listed as endangered in our state. More than other members of the rail family in our state, King Rail numbers seem to be greatly reduced in comparison to the early 20th Century, and it has been nearly extirpated from the state. Field observation data that document confirmed or probable breeding of King Rails at a specific habitat for at least 2 years of the previous 6 years (the years being considered roll forward annually) are needed for Iowaʼs IBA Technical Committee to recognize that site as one of Iowaʼs Important Bird Areas (IBAs). The King Rail is dependent upon marshes and wetlands where its secretive behavior may make it difficult to find. But at times it may be seen rather boldly stalking along marsh edges in full view of observers. Up until about 50 years ago, the King Rail was fairly common in Iowa, but it has declined alarmingly in the past 30-50 years. This trend is almost certainly due to the loss and/or degradation of the wetlands that this species is dependents upon. King Rails are the most threatened rail in North America. Fewer than a dozen adults of this species were reported in most recent years, and these reports are primarily from areas near the Mississippi River, or from the prairie pothole region of north-central and northwestern Iowa.