Glee: Give Us Something to Sing About Phoebe Bronstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Hot in Cleveland” Airs 100Th Episode on Wednesday, August 27Th

“HOT IN CLEVELAND” AIRS 100TH EPISODE ON WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 27TH New York, NY – August 26, 2014 – TV Land’s hit sitcom “Hot in Cleveland,” starring Valerie Bertinelli, Jane Leeves, Wendie Malick and Betty White, is hitting a huge milestone with its 100th taped episode, entitled “Win, Win,” airing on Wednesday, August 27th at 10pm ET/PT. “Win, Win” will see a big night for the Clevelanders – Elka (White), who is at the finish line for her City Council election, and Victoria (Malick), who is up for an Academy Award at long last, with Joy (Leeves) and Melanie (Bertinelli) in tow. The episode also guest stars Debra Monk (“Damages”) as Melanie’s mother and Georgia Engel, back as Elka’s best friend Mamie Sue. “When we first pulled together this group of extraordinary women and saw their chemistry, we knew it had everything we wanted for our first original sitcom,” said Larry W. Jones, President of TV Land. “Before ‘Hot in Cleveland,’ there hadn’t been a comedy in decades that explored life’s funny moments for women over 40, and now in just four short years, we’ve reached 100 episodes and have fans of all ages tuning in every week. We couldn’t be prouder and more excited for the cast, crew and all the people who worked so hard to get ‘Hot in Cleveland’ to this landmark occasion.” “Hot in Cleveland,” currently in its fifth season and in production on its sixth, has seen some amazing guest stars over the past four years, ranging from Chris Colfer, Jesse Tyler Ferguson and Jennifer Love Hewitt to Carol Burnett, Carl Reiner and a full reunion of the female cast of “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” – Mary Tyler Moore, Cloris Leachman, Valerie Harper, Georgia Engel, and of course, series star Betty White. -

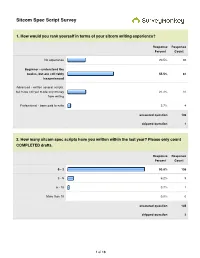

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

Saluting Cheyenne Jackson for Artistic Achievement

Saluting Cheyenne Jackson for artistic achievement WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson is a native of the Pacific Northwest who has shown that even through adversity and hardship, one can make their dreams come true; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has appeared in films such as the Academy Award nominated United 93, the Sundance selected Price Check, and The Green; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has also appeared on television programs such as Glee, Ugly Betty, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and 30 Rock; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has appeared in such Broadway and off-Broadway productions as All Shook Up, The Agony and The Agony, The Heart of the Matter, and 8; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has recorded two studio albums and has sold out Carnegie Hall twice; and WHEREAS, his work on Broadway, on television, in film and his activism on behalf of the LGBT community through his work with the Foundation for AIDS research and the Hetrick-Martin Institute which supports LGBT youth have been a source of inspiration for many in our community; and WHEREAS, we are proud to welcome Cheyenne Jackson back to the Pacific Northwest for his performance at Martin Woldson Theater in the hopes that his work will inspire many more; NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED, by the Spokane City Council that we hereby salute Cheyenne Jackson for all of his accomplishments and look forward to his performance with the Spokane Symphony. I, Ben Stuckart, Spokane City Council President, do hereunto set my hand and cause the seal of the City of Spokane to be affixed this 19th day of May in 2014 Ben Stuckart Spokane City Council President . -

A Brief History of the Morehouse College Glee Club

A Brief History of the Morehouse College Glee Club The Morehouse College Glee Club is the premier singing organization of Morehouse College, traveling all over the country and the world, demonstrating excellence not only in choral performance but also in discipline, dedication, and brotherhood. Through its tradition the Glee Club has an impressive history and seeks to secure its future through even greater accomplishments, continuing in this tradition through the dedication and commitment of its members and the leadership that its directors have provided throughout the years. It is the mission of the Morehouse College Glee Club to maintain a high standard of musical excellence. In 1911, Morehouse College, then under the name of Atlanta Baptist College, had a music professor named Georgia Starr. She served the College from 1903-1905 and again from 1908- 1911. Mr. Kemper Harreld, who officially founded the Morehouse College Glee Club, assumed leadership when he joined the College’s music faculty in the fall of 1911. Mr. Harreld became both, Chair of the Music Department and Director of the Glee Club. After faithfully serving for forty-two years, he retired in 1953. Mr. Harreld was responsible for beginning the Glee Club’s strong legacy of excellence that has since been passed down to all members of the organization. The Glee Club’s history continues in 1953 with the second director, Wendell Phillips Whalum, Sr., '52. Dr. Whalum was a prized student of Kemper Harreld. He served as Student Director during his tenure in the Glee Club. Dr. Whalum, was more commonly known as "Doc", and served Morehouse College and the Glee Club with the continued tradition of excellence through expanded repertoire and national and international exposure throughout his tenure at the College. -

Rutgers University Glee Club Fall 2020 – Audition Results Tenor 1

Rutgers University Glee Club Fall 2020 – Audition results Congratulations and welcome to the start of a great new year of music making. Please register for the Rutgers University Glee Club immediately – Course 07 701 349. If you are a music major and have any issues with registration please contact Ms. Leibowitz. Non majors with questions please email Dr. Gardner – [email protected]. Glee Club rehearases on Weds nights from 7 to 10 pm and Fridays from 2:50 to 4:10 pm on-line. The zoom link and syllabus is available in Canvas. First rehearsal is this coming Wednesday, September 9th. See you there! Tenor 1 Tenor 2 Baritone Bass Maxwell Domanchich Billy Colletto III Ryan Acevedo James Carson Tin Fung Sean Dekhayser Kyle Cao John DeMarco Jonathan Germosen Steve Franklin Jeffrey Greiner Duff Heitmann Joseph Maldonado James Hwang Tristan Kilper Jonathan Ho Khuti Moses Benjamin Kritz Brian Kong Emerson Katz-Justice Aditya Nibhanupudi Matthew Mallick Matthew Lacognata Seonuk Kim Michael O'Neill Amartya Mani Michael Lazarow Allen Li Michael Schaming Gene Masso Ryan Leibowitz Gabriel Lukijaniuk Xerxes Tata Conor Wall Carl Muhler Sean McBurney Harry Thomas Bobby Weil Julian Perelman Joseph Mezza Zachary Wang John Wilson Caleb Schneider AJ Pandey Nathaniel Barnett Samuel Wilson Gianmarco Scotti Thomas Piatkowski Josh Gonzalez Patrick Cascia Kolter Yagual-Ralston Guillermo Pineiro Kyle Casem Nicholas Casey Nathaniel Eck Ross Ferguson Sachin Boteju Mike Semancik Michael Munza Evan Dickonson Soroush Gharavi Jason Bedianko Colin Smith Benjamin Shanofsky . -

Chris Colfer Was Born on May 27, 1990, in the United States, but Is of Irish Heritage

Introduction LGBTQ+ History Month is a very important time to recognize and bring awareness to people of all genders and orientations. There are many events this month dedicated to the history of the LGBTQ+ community and its awareness. These events include: National Coming Out Day, Ally Week, Spirit Day, the first “March on Washington,” and the celebration of the life of Matthew Shepard, who was killed in a hate crime in 1998. The very first LGBTQ+ History Month was celebrated in 1994, and recognized as an official commemorative national month in 1995. As a sociology class, we want each person to feel represented and acknowledged at MSA. No gender, orientation, ethnicity, or race should go unrecognized. The intent of this project is to celebrate everyone, and bring about awareness that represents the LGBTQ+ community and their allies. Anna Eleanor Roosevelt was born on Franklin was struck with polio in 1921 and October 11, 1884 in New York City, New Eleanor Roosevelt as a result Eleanor decided to help his York. She grew up in quite a wealthy family political career. She became very active in but also they were greatly invested in the Democratic Party and started to learn helping the community out. Sadly both her patterns of debates and voting records. He parents died before she turned 10 and it became governor in 1929 which made her tore her apart. When she turned 15, she the First Lady of the State. Later while FDR started attending a boarding school strictly was president, she became the First Lady of for girls called Allenswood.She was the US. -

September 2010 Cinemann Table of Contents

September 2010 Cinemann Table of Contents 4 Summer Inception Movie Recap 6 Letter From the Editors 14 The Big C 8 Summer Television 15 Rent 10 The Emmy Awards Cinemann 2 Cinemann: Volume VI, Issue 1 Editors in Chief )--.#,"&0(1*,&./- 5.6&/,7$&,68(4/,&0/-! Andrew Demas !"#$%&!'#()*+%,-!.&,,%(#!'/%-! 9#(/&3!:*%,,&+&$/-!21%,&! 0)&!"&,$#1-! '/#+3&,-!;#<%=!>&*&+,$&%1-! Maggie Reinfeld .#()?!>+#(@6#1-!2?%A#%3! Senior Editors 2&"33(4/,&0/- B+&&1?#*6-!:&11&$$!C&33&+-! Matt Taub 23%(&!4#+#1$)-!5#6!4)++&,-! D)#/!E#+A*3%,-!.#F!G#3&H Alexandra Saali '/#+3&,!5/&++-!766#!58&($&+ @#+-!5#<#11#/!56%$/-!9#H (/&3!5%6&+@#H56%$/-!C&1+F! !"#$%&'()*+,-./ I#+=&+ !"#$%&'()&**"+ Letter From the EditorsDear Reader, Welcome back!! We are so thrilled to present you with WKHÀUVWLVVXHRICinemann,+RUDFH0DQQ·VÀOPDQGDUWV PDJD]LQH$V\RXVLIWWKURXJKWKHSDJHVZHKRSH\RX SOXQJHLQWRWKHMR\VRIWKLVVXPPHU·VPRYLHVDQGDUW ,QVLGH\RXZLOOÀQGDQDUUD\RIUHYLHZV%HJLQQLQJZLWK a look at summer’s highest grossing blockbusters, as ZHOODVLWVXQH[SHFWHGÁRSVZHZLOODOVREULQJ\RXXSWR GDWHZLWKUHYLHZVRIVXPPHUWHOHYLVLRQDQGWKHDWHUCin- emannGHOYHVLQWRKRZWKHLQQRYDWLYHSORWVRIWKHEULO- OLDQWO\FUDIWHG,QFHSWLRQDQGWKHUDXQFK\FRPHG\-HUVH\ 6KRUHKDYHWUDQVÀ[HGYLHZHUV&RPHG\VHHPHGWRUXOH at the 2010 Emmy Awards, and we are here to show you why. Inside we recount the night’s biggest moments and HYDOXDWHWKHGHFLVLRQEHKLQGWKHUHVXOWV:HURXQGRXW WKLVLVVXHZLWKDUHYLHZRI1HLO3DWULFN+DUULV·UHYLYDO RIRentDWWKH+ROO\ZRRG%RZOH[SORULQJWKHYHU\QD- WXUHRIWKHFKDOOHQJHVLQYROYHGLQUHVWDJLQJDFODVVLF:H hope you enjoy it. ,I\RXZRXOGOLNHWRZULWHIRU&LQHPDQQSOHDVHFRQWDFW -

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

Download Choosing Glee

Choosing Glee: 10 Rules to Finding Inspiration, Happiness, and the Real You, Jenna Ushkowitz, Sheryl Berk, St. Martin's Press, 2013, 1250030617, 9781250030610, 224 pages. Glee star Jenna Ushkowitz, a.k.a. "Tina," inspires fans to invoke positive thinking into everything they do in this inspirational scrapbook.Time to Gleek out!Fans of the breakout musical series will flock to Ushkowitz’s heartfelt and practical guide on how to be your true self, gain self-esteem, and find your inner confidence. In Choosing Glee, Jenna shares her life in thrall to performance, navigating the pendulum swing of rejection and success, and the lessons she learned along the way. Included are her vivid anecdotes of everything before and after Glee: her being adopted from South Korea; her early appearances in commercials and on Sesame Street; her first Broadway role in The King and I; landing the part of Tina on Glee; her long-time friendships with Lea Michele (a.k.a. Rachel Berry) and Kevin McHale (a.k.a. Artie); and touring the world singing the show’s hits to stadium crowds. Peppered throughout are photos, keepsakes, lists, and charts that illustrate Jenna's life and the choices she has made that have shaped her positive outlook.Choosing Glee will speak to the show's demographic who are often coping with the very stresses and anxieties the teenage characters on Glee face. Think The Happiness Project for a younger generation: With its uplifting message and intimate format, teens can learn how, exactly, to choose glee. -

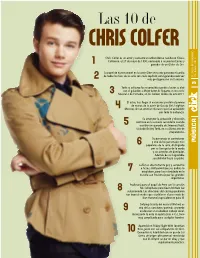

Chris Colfer

Las 10 de chris colfer Chris Colfer es un actor y cantante estadounidense nacido en Clovis, California, el 27 de mayo de 1990, nominado a un premio Emmy y 1 ganador de un Globo de Oro. Su papel de Kurt Hummel en la serie Glee se ha ido ganando el cariño de todos los fans de la serie con cada capítulo, consiguiendo cada vez EL SIGLO DE DURANGO 29 • Enero • 2011 2 más protagonismo en la misma. 3 Todo su esfuerzo fue reconocido cuando el actor se alzó con el galardón a Mejor Actor de Reparto en una serie 3 Musical o de Comedia, en los Golden Globes de este 2011. El actor, tras llegar al escenario y recibir el premio de manos de la actriz de Gossip Girl, Leighton 4 Meester, dio un emotivo discurso que fue aplaudido por toda la audiencia. Su amor por la actuación y dirección continuó en la escuela secundaria cuando A 5 escribió una parodia de Sweeney Todd, titulado Shirley Todd, en su último año de IC preparatoria. Su personaje es contratenor y uno de los personajes más MÚS 6 populares de la serie, distinguido por su fino gusto de la moda y sus prendas de diseñador. Además de su inigualable sensibilidad hacia su padre. Colfer es abiertamente gay y compartió a Access Hollywood que sus padres lo 7 aceptaban, pero fue intimidado en la escuela con frecuencia por los grandes deportistas. Audicionó para el papel de Artie con la canción Mr. Cellophane pero Kevin McHale fue 8 seleccionado. Los directores del casting quedaron tan impresionados que escribieron el personaje de Kurt Hummel especialmente para él. -

The Glee News

Inside:The Times of Glee Fox to end ‘Glee’? Kurt Hummel recieves great reviews on his The co-creator of Fox’s great acting, sining, and “Glee” has revealed dancing in his debut “Funny Girl” star Rachel Berry is photographed on the streets of New York plans to end the series, role of “Peter Pan”. walking five dogs. She will soon drop the news about her dog adoption Us Weekly reports. Ryan event. Murphy told reporters Wednesday in L.A. that the musical series will New meaning to “dog eats end its run next year after six seasons. The end of the show ap- dog” business pears to be linked to the Rising actors Berry and Hummel host Brod- death of Cory Monteith, one of its stars. Chris Colfer expands way themed dog show In the streets of New York, happy to be giving back. “After the emotional his talent from simple the three-legged dog to the Rachel uncertainly leads mother and her son. The three friends share a memorial episode for an actor and musician a dozen dogs on leads group hug, happily. Monteith and his char- to a screenplay wiriter through the street. Blaine Sam suggests to Mercedes acter Finn Hudson aired and Artie have positioned that they give McCo- “Old Dog New Tricks” is as well. last week, Murphy said themselves among some naughey to someone at the written by Chris Colfer, who it’s been very difficult to event, but Mercedes tells lunching papparazi, and claims his “two favorite move on with the show,” him to not bother - they’re loudly announce her arriv- cording things in life are animals the story reports. -

US, JAPANESE, and UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, and the CONSTRUCTION of TEEN IDENTITY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by British Columbia's network of post-secondary digital repositories BLOCKING THE SCHOOL PLAY: US, JAPANESE, AND UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF TEEN IDENTITY by Jennifer Bomford B.A., University of Northern British Columbia, 1999 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2016 © Jennifer Bomford, 2016 ABSTRACT School spaces differ regionally and internationally, and this difference can be seen in television programmes featuring high schools. As television must always create its spaces and places on the screen, what, then, is the significance of the varying emphases as well as the commonalities constructed in televisual high school settings in UK, US, and Japanese television shows? This master’s thesis considers how fictional televisual high schools both contest and construct national identity. In order to do this, it posits the existence of the televisual school story, a descendant of the literary school story. It then compares the formal and narrative ways in which Glee (2009-2015), Hex (2004-2005), and Ouran koukou hosutobu (2006) deploy space and place to create identity on the screen. In particular, it examines how heteronormativity and gender roles affect the abilities of characters to move through spaces, across boundaries, and gain secure places of their own. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgement v Introduction Orientation 1 Space and Place in Schools 5 Schools on TV 11 Schools on TV from Japan, 12 the U.S., and the U.K.