THE STORY of an IDEA MOVING with a PLAYMAKING EDUCATION by Donard Anthony James Mackenzie B.F.A. (Theatre), University of Victor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

230-Newsletter.Pdf

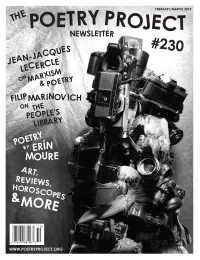

$5? The Poetry Project Newsletter Editor: Paul Foster Johnson Design: Lewis Rawlings Distribution: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff Artistic Director: Stacy Szymaszek Program Coordinator: Arlo Quint Program Assistant: Nicole Wallace Monday Night Coordinator: Macgregor Card Monday Night Talk Series Coordinator: Josef Kaplan Wednesday Night Coordinator: Stacy Szymaszek Friday Night Coordinator: Brett Price Sound Technician: David Vogen Videographer: Andrea Cruz Bookkeeper: Stephen Rosenthal Archivist: Will Edmiston Box Office: Courtney Frederick, Vanessa Garver, Jeffrey Grunthaner Interns/Volunteers: Nina Freeman, Julia Santoli, Alex Duringer, Jim Behrle, Christa Quint, Judah Rubin, Erica Wessmann, Susan Landers, Douglas Rothschild, Alex Abelson, Aria Boutet, Tony Lancosta, Jessie Wheeler, Ariel Bornstein Board of Directors: Gillian McCain (President), Rosemary Carroll (Treasurer), Kimberly Lyons (Secretary), Todd Colby, Mónica de la Torre, Ted Greenwald, Tim Griffin, John S. Hall, Erica Hunt, Jonathan Morrill, Elinor Nauen, Evelyn Reilly, Christopher Stackhouse, Edwin Torres Friends Committee: Brooke Alexander, Dianne Benson, Raymond Foye, Michael Friedman, Steve Hamilton, Bob Holman, Viki Hudspith, Siri Hustvedt, Yvonne Jacquette, Patricia Spears Jones, Eileen Myles, Greg Masters, Ron Padgett, Paul Slovak, Michel de Konkoly Thege, Anne Waldman, Hal Willner, John Yau Funders: The Poetry Project’s programs are made possible, in part, with public funds from The National Endowment for the Arts. The Poetry Project’s programming is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; and are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council. -

1What Is a Novel?

WhatWHAT is ISa ANovel? NOVEL? WHAT1 IS A NOVEL? novel is a piece of prose fiction of a reasonable length. Even a definition as toothless as this, however, is still too restricted. Not A all novels are writtten in prose. There are novels in verse, like Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin or Vikram Seth’s The Golden Gate. As for fiction, the distinction between fiction and fact is not always clear. And what counts as a reasonable length? At what point does a novella or long short story become a novel? André Gide’s The Immoralist is usually described as a novel, and Anton Chekhov’s ‘The Duel’ as a short story, but they are both about the same length. The truth is that the novel is a genre which resists exact definition. This in itself is not particularly striking, since many things – ‘game’, for example, or ‘hairy’ – resist exact definition. It is hard to say how ape-like you have to be in order to qualify as hairy. The point about the novel, however, is not just that it eludes definitions, but that it actively undermines them. It is less a genre than an anti-genre. It cannibalizes other literary modes and mixes the bits and pieces promiscuously together. You can find poetry and dramatic dialogue in the novel, along with epic, pastoral, satire, history, elegy, trag- edy and any number of other literary modes. Virginia Woolf described it as ‘this most pliable of all forms’. The novel quotes, parodies and transforms other genres, converting its literary ancestors into mere components of itself in a kind of Oedipal vengeance on them. -

Download PDF to Read Full Article from Apollo Magazine

INTERVIEW I By Stuart Rowland In an exclusive celebrity interview for Apollo Executive Review, Stuart Rowlands talks to Michael I like to keep testing the waters… York “In late December 2007 I got back to Los If the answer is “YES!” to the question Angeles after filming in Russia, Germany, “do you want to act and you are aged Poland and Israel”, he remembers. “2008 ” got off to a quick start with the continued between 13 and 21, the National Youth narration of a new audio version of the entire Bible – a huge undertaking that would Theatre, Britain's Premiere youth theatre take most of the year to complete. This was followed by a recording of Alan Paton’s company, is just the place for you! extraordinary classic tale of apartheid in South Africa, Cry the Beloved Country. Next or a sixteen year old schoolboy from was a project very dear to my heart - Bromley, Kent, the school board performing with the Long Beach Opera Fnotice was a siren song to the start of company on a very daring double bill, a career that has spanned nearly 45 years Strauss Meets Frankenstein” . and shows absolutely no signs of slowing By March, Michael and his wife Pat were down. In fact Michael York has no plans to headed east to Maine where Pat, a celebrated retire. In late December, a few days before and published photographer, was shooting Christmas, he has finally returned to his renowned American ‘pop art movement home high in the Hollywood Hills above Los icon’ artist Robert Indiana for a new book. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 2000 The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints Donald W. Parry Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Parry, Donald W. and Ricks, Stephen D., "The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints" (2000). Maxwell Institute Publications. 25. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Preface What is the Copper Scroll? Do the Dead Sea Scrolls contain lost books of the Bible? Did John the Baptist study with the people of Qumran? What is the Temple Scroll? What about DNA research and the scrolls? We have responded to scores of such questions on many occasions—while teaching graduate seminars and Hebrew courses at Brigham Young University, presenting papers at professional symposia, and speaking to various lay audiences. These settings are always positive experiences for us, particularly because they reveal that the general membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a deep interest in the scrolls and other writings from the ancient world. The nonbiblical Dead Sea Scrolls are of great import because they shed much light on the cultural, religious, and political position of some of the Jews who lived shortly before and during the time of Jesus Christ. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

The Ithacan, 1997-09-18

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1997-98 The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 9-18-1997 The thI acan, 1997-09-18 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1997-98 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1997-09-18" (1997). The Ithacan, 1997-98. 4. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1997-98/4 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1997-98 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Op1n1on Accenr SpoRTS Inoex Accent ....................... 13 Privacy Invasion Different Beat No"O" Classified ................... 2:3 Shower voyeurs Rave descends on Opening blues for Comics. .... ....... 24 should recognize 10 Ithaca Bomber football Opinion .................. 10 impacts of spying 13 27 Sports ....................... 25 The IT The Newspaper for the Ithaca College Community VOLUME 65, NUMBER 4 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 1997 32 PAGl:S, FRI:!: Student suspended on campu~ ground~ urllil 1he ~,1u Scott Ernst no longer at College; at1on wa~ re~olvcd. ··1 am not hil ler or re\cntl ul tov. artb ,111yom: 111 football player to return home the ,y,tem," K1111 ,a1tl. ""The) Court on Wedne~day night and coulJ ha\e handkJ 11 a better By Adam B. Ellick pleaded guilty to two v1olat1011~· way, a lairn way I never h,1d lhL· Ithacan Staff hara~~mcnt and di~ordcrly con chance lo confront our ,tccuwr, ·· Scott Ernst '98 is no longer a duct. -

Heartoflove.Pdf

Contents Intro............................................................................................................................................................. 18 Indian Mystics ............................................................................................................................................. 20 Brahmanand ............................................................................................................................................ 20 Palace in the sky .................................................................................................................................. 22 The Miracle ......................................................................................................................................... 23 Your Creation ...................................................................................................................................... 25 Prepare Yourself .................................................................................................................................. 27 Kabir ........................................................................................................................................................ 29 Thirsty Fish .......................................................................................................................................... 30 Oh, Companion, That Abode Is Unmatched ....................................................................................... 31 Are you looking -

THE LIBRARY MAGAZINE of SELECT FOREIGN LITERATURE VOLUME 1 by Various

THE LIBRARY MAGAZINE OF SELECT FOREIGN LITERATURE VOLUME 1 By Various THE LIBRARY MAGAZINE JANUARY, 1879. THE FUTURE OF INDIA. Speculation as to the political future is not a very fruitful occupation. In looking back to the prognostications of the wisest statesmen, it will be observed that they were as little able to foresee what was to come a generation or two after their death, as the merest dolt amongst their contemporaries. The Whigs at the beginning of the last century thought that the liberties of Europe would disappear if a prince of the House of Bourbon were securely fixed on the throne of Spain. The Tories in the last quarter of that century considered that if England lost her American provinces she would sink into the impotence of the Dutch Republic. The statesmen who assembled at the Congress of Vienna would have laughed any dreamer to scorn who should have suggested that in the lifetime of many of them Germany would become an empire in the hands of Prussia, France a well-organized and orderly republic, and the "geographical expression" of Italy vitalised into one of the great powers of Europe. Nevertheless, if politics is ever to approach the dignity of a science, it must justify a scientific character by its ability to predict events. The facts are too complicated, probably, ever to admit the application of exact deductive reasoning; and in the growth of civilised society new and unexpected forms are continually springing up. But though practical statesmen will not aim at results beyond the immediate future, it is impossible for men who pass their lives in the study of the difficult task of government to avoid speculations as to the future form of society to which national efforts should be directed. -

Infrastructure and Everyday Life in Paris, 1870-1914

The Fragility of Modernity: Infrastructure and Everyday Life in Paris, 1870-1914 by Peter S. Soppelsa A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Joshua H. Cole, Co-Chair Associate Professor Gabrielle Hecht, Co-Chair Professor Richard Abel Professor Geoffrey H. Eley Associate Professor Dario Gaggio Copyright 2009 Peter S. Soppelsa For Jen, who saw me through the whole project. ii Contents Dedication ii List of Figures iv Introduction: Modernity, Infrastructure and Everyday Life 1 Chapter 1: Paris, Modernity and Haussmann 35 Part One: Circulation, The Flow of Traffic 99 Chapter 2: The Dream Life of the Métropolitain, 1872-1895 107 Chapter 3: Paris Under Construction, 1895-1914 182 Part Two: Hygiene, The Flow of Light, Air, Water and Waste 253 Chapter 4: Opening the City: Housing, Hygiene and Urban Density 265 Chapter 5: Flows of Water and Waste 340 Conclusion: The Fragility of Modernity 409 Bibliography 423 iii List of Figures Figure 1: Morice's Marianne on the Place de la République 74 Figure 2: The departmental commission's 1872 Métro plan 120 Figure 3: A standard CGO horse-powered tram 122 Figure 4: CGO Mékarski system compressed air tram, circa 1900 125 Figure 5: Francq's locomotive sans foyer 127 Figure 6: Albert Robida, L'Embellissement de Paris par le métropolitain (1886) 149 Figure 7: Jules Garnier’s Haussmannized Viaduct, 1884 153 Figure 8: From Louis Heuzé's 1878 Pamphlet 154 Figure 9: From Louis Heuzé's 1878 Pamphlet 154 Figure 10: Le Chatelier's 1889 Métro Plan 156 Figure 11: 1890 Métro plan from Eiffel and the North Railway Company 163 Figure 12: J.B. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE