Primary Mesenchymal Stem and Progenitor Cells from Bone Marrow Lack Expression of CD44 Protein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of Cyclosporine in Gingival Hyperplasia: an in Vitro Study on Gingival Fibroblasts

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Role of Cyclosporine in Gingival Hyperplasia: An In Vitro Study on Gingival Fibroblasts 1, , 2, 3 3 Dorina Lauritano * y , Annalisa Palmieri y, Alberta Lucchese , Dario Di Stasio , Giulia Moreo 1 and Francesco Carinci 4 1 Department of Medicine and Surgery, Centre of Neuroscience of Milan, University of Milano-Bicocca, 20126 Milan, Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of Experimental, Diagnostic and Specialty Medicine, University of Bologna, via Belmoro 8, 40126 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] 3 Multidisciplinary Department of Medical and Dental Specialties, University of Campania-Luigi Vanvitelli, 80138 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (D.D.S.) 4 Department of Morphology, Surgery and Experimental Medicine, University of Ferrara, 44121 Ferrara, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-335-679-0163 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 25 November 2019; Accepted: 13 January 2020; Published: 16 January 2020 Abstract: Background: Gingival hyperplasia could occur after the administration of cyclosporine A. Up to 90% of the patients submitted to immunosuppressant drugs have been reported to suffer from this side effect. The role of fibroblasts in gingival hyperplasia has been widely discussed by literature, showing contrasting results. In order to demonstrate the effect of cyclosporine A on the extracellular matrix component of fibroblasts, we investigated the gene expression profile of human fibroblasts after cyclosporine A administration. Materials and methods: Primary gingival fibroblasts were stimulated with 1000 ng/mL cyclosporine A solution for 16 h. Gene expression levels of 57 genes belonging to the “Extracellular Matrix and Adhesion Molecules” pathway were analyzed using real-time PCR in treated cells, compared to untreated cells used as control. -

Supplemental Information to Mammadova-Bach Et Al., “Laminin Α1 Orchestrates VEGFA Functions in the Ecosystem of Colorectal Carcinogenesis”

Supplemental information to Mammadova-Bach et al., “Laminin α1 orchestrates VEGFA functions in the ecosystem of colorectal carcinogenesis” Supplemental material and methods Cloning of the villin-LMα1 vector The plasmid pBS-villin-promoter containing the 3.5 Kb of the murine villin promoter, the first non coding exon, 5.5 kb of the first intron and 15 nucleotides of the second villin exon, was generated by S. Robine (Institut Curie, Paris, France). The EcoRI site in the multi cloning site was destroyed by fill in ligation with T4 polymerase according to the manufacturer`s instructions (New England Biolabs, Ozyme, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France). Site directed mutagenesis (GeneEditor in vitro Site-Directed Mutagenesis system, Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) was then used to introduce a BsiWI site before the start codon of the villin coding sequence using the 5’ phosphorylated primer: 5’CCTTCTCCTCTAGGCTCGCGTACGATGACGTCGGACTTGCGG3’. A double strand annealed oligonucleotide, 5’GGCCGGACGCGTGAATTCGTCGACGC3’ and 5’GGCCGCGTCGACGAATTCACGC GTCC3’ containing restriction site for MluI, EcoRI and SalI were inserted in the NotI site (present in the multi cloning site), generating the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. The SV40 polyA region of the pEGFP plasmid (Clontech, Ozyme, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France) was amplified by PCR using primers 5’GGCGCCTCTAGATCATAATCAGCCATA3’ and 5’GGCGCCCTTAAGATACATTGATGAGTT3’ before subcloning into the pGEMTeasy vector (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France). After EcoRI digestion, the SV40 polyA fragment was purified with the NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Machery-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) and then subcloned into the EcoRI site of the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. Site directed mutagenesis was used to introduce a BsiWI site (5’ phosphorylated AGCGCAGGGAGCGGCGGCCGTACGATGCGCGGCAGCGGCACG3’) before the initiation codon and a MluI site (5’ phosphorylated 1 CCCGGGCCTGAGCCCTAAACGCGTGCCAGCCTCTGCCCTTGG3’) after the stop codon in the full length cDNA coding for the mouse LMα1 in the pCIS vector (kindly provided by P. -

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

Supplemental Figure 1. Vimentin

Double mutant specific genes Transcript gene_assignment Gene Symbol RefSeq FDR Fold- FDR Fold- FDR Fold- ID (single vs. Change (double Change (double Change wt) (single vs. wt) (double vs. single) (double vs. wt) vs. wt) vs. single) 10485013 BC085239 // 1110051M20Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1110051M20 gene // 2 E1 // 228356 /// NM 1110051M20Ri BC085239 0.164013 -1.38517 0.0345128 -2.24228 0.154535 -1.61877 k 10358717 NM_197990 // 1700025G04Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1700025G04 gene // 1 G2 // 69399 /// BC 1700025G04Rik NM_197990 0.142593 -1.37878 0.0212926 -3.13385 0.093068 -2.27291 10358713 NM_197990 // 1700025G04Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1700025G04 gene // 1 G2 // 69399 1700025G04Rik NM_197990 0.0655213 -1.71563 0.0222468 -2.32498 0.166843 -1.35517 10481312 NM_027283 // 1700026L06Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1700026L06 gene // 2 A3 // 69987 /// EN 1700026L06Rik NM_027283 0.0503754 -1.46385 0.0140999 -2.19537 0.0825609 -1.49972 10351465 BC150846 // 1700084C01Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1700084C01 gene // 1 H3 // 78465 /// NM_ 1700084C01Rik BC150846 0.107391 -1.5916 0.0385418 -2.05801 0.295457 -1.29305 10569654 AK007416 // 1810010D01Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1810010D01 gene // 7 F5 // 381935 /// XR 1810010D01Rik AK007416 0.145576 1.69432 0.0476957 2.51662 0.288571 1.48533 10508883 NM_001083916 // 1810019J16Rik // RIKEN cDNA 1810019J16 gene // 4 D2.3 // 69073 / 1810019J16Rik NM_001083916 0.0533206 1.57139 0.0145433 2.56417 0.0836674 1.63179 10585282 ENSMUST00000050829 // 2010007H06Rik // RIKEN cDNA 2010007H06 gene // --- // 6984 2010007H06Rik ENSMUST00000050829 0.129914 -1.71998 0.0434862 -2.51672 -

Epithelial-Specific Knockout of the Rac1 Gene Leads to Enamel Defects

Eur J Oral Sci 2011; 119 (Suppl. 1): 168–176 Ó 2011 Eur J Oral Sci DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2011.00904.x European Journal of Printed in Singapore. All rights reserved Oral Sciences Zhan Huang1, Jieun Kim2, Rodrigo Epithelial-specific knockout of the Rac1 S. Lacruz1, Pablo Bringas Jr1, Michael Glogauer3, Timothy G. gene leads to enamel defects Bromage4, Vesa M. Kaartinen2, Malcolm L. Snead1 1The Center for Craniofacial Molecular Biology, Huang Z, Kim J, Lacruz RS, Bringas P Jr, Glogauer M, Bromage TG, Kaartinen VM, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Snead ML. Epithelial-specific knockout of the Rac1 gene leads to enamel defects. 2 Eur J Oral Sci 2011; 119 (Suppl. 1): 168–176. Ó 2011 Eur J Oral Sci Department of Biologic and Materials Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; 3Matrix The Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) gene encodes a 21-kDa GTP- Dynamics Group, Faculty of Dentistry, binding protein belonging to the RAS superfamily. RAS members play important University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, roles in controlling focal adhesion complex formation and cytoskeleton contraction, Canada; 4New York University College of activities with consequences for cell growth, adhesion, migration, and differentiation. Dentistry, New York, NY, USA To examine the role(s) played by RAC1 protein in cell–matrix interactions and enamel matrix biomineralization, we used the Cre/loxP binary recombination system to characterize the expression of enamel matrix proteins and enamel formation in Rac1 knockout mice (Rac1)/)). Mating between mice bearing the floxed Rac1 allele and mice bearing a cytokeratin 14-Cre transgene generated mice in which Rac1 was absent Zhan Huang, The Center for Craniofacial from epithelial organs. -

Newly Developed Serine Protease Inhibitors Decrease Visceral Hypersensitivity in a Post-Inflammatory Rat Model for Irritable Bowel Syndrome

This item is the archived peer-reviewed author-version of: Newly developed serine protease inhibitors decrease visceral hypersensitivity in a post-inflammatory rat model for irritable bowel syndrome Reference: Ceuleers Hannah, Hanning Nikita, Heirbaut Leen, Van Remoortel Samuel, Joossens Jurgen, van der Veken Pieter, Francque Sven, De Bruyn Michelle, Lambeir Anne-Marie, de Man Joris, ....- New ly developed serine protease inhibitors decrease visceral hypersensitivity in a post-inflammatory rat model for irritable bow el syndrome British journal of pharmacology - ISSN 0007-1188 - 175:17(2018), p. 3516-3533 Full text (Publisher's DOI): https://doi.org/10.1111/BPH.14396 To cite this reference: https://hdl.handle.net/10067/1530780151162165141 Institutional repository IRUA NEWLY DEVELOPED SERINE PROTEASE INHIBITORS DECREASE VISCERAL HYPERSENSITIVITY IN A POST-INFLAMMATORY RAT MODEL FOR IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME. Running title: Serine proteases in visceral hypersensitivity Hannah Ceuleers, Nikita Hanning, Jelena Heirbaut, Samuel Van Remoortel, Michelle De bruyn, Jurgen Joossens, Pieter van der Veken, Anne-Marie Lambeir, Sven M Francque, Joris G De Man, Jean-Pierre Timmermans, Koen Augustyns, Ingrid De Meester, Benedicte Y De Winter Hannah Ceuleers, Nikita Hanning, Jelena Heirbaut, Sven Francque, Joris G De Man, Benedicte Y De Winter, Laboratory of Experimental Medicine and Pediatrics, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium. Samuel Van Remoortel, Jean-Pierre Timmermans, Laboratory of Cell Biology and Histology, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium. Jurgen Joossens, Pieter van der Veken, Koen Augustyns, Laboratory of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium. Sven Francque, Antwerp University Hospital, Antwerp, Belgium. Michelle De bruyn, Anne-Marie Lambeir, Ingrid De Meester, Laboratory of Medical Biochemistry, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium. -

2335 Roles of Molecules Involved in Epithelial/Mesenchymal Transition

[Frontiers in Bioscience 13, 2335-2355, January 1, 2008] Roles of molecules involved in epithelial/mesenchymal transition during angiogenesis Giulio Ghersi Dipartimento di Biologia Cellulare e dello Sviluppo, Universita di Palermo, Italy TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Abstract 2. Introduction 3. Extracellular matrix 3.1. ECM and integrins 3.2. Basal lamina components 4. Cadherins. 4.1. Cadherins in angiogenesis 5. Integrins. 5.1. Integrins in angiogenesis 6. Focal adhesion molecules 7. Proteolytic enzymes 7.1. Proteolytic enzymes inhibitors 7.2. Proteolytic enzymes in angiogenesis 8. Perspective 9. Acknowledgements 10. References 1.ABSTRACT 2. INTRODUCTION Formation of vessels requires “epithelial- Growth of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) mesenchymal” transition of endothelial cells, with several plays a key role in several physiological processes, such modifications at the level of endothelial cell plasma as vascular remodeling during embryogenesis and membranes. These processes are associated with wound healing tissue repair in the adult; as well as redistribution of cell-cell and cell-substrate adhesion pathological processes, including rheumatoid arthritis, molecules, cross talk between external ECM and internal diabetic retinopathy, psoriasis, hemangiomas, and cytoskeleton through focal adhesion molecules and the cancer (1). Vessel formation entails the “epithelial- expression of several proteolytic enzymes, including matrix mesenchymal” transition of endothelial cells (ECs) “in metalloproteases and serine proteases. These enzymes with vivo”; a similar phenotypic exchange can be induced “in their degradative action on ECM components, generate vitro” by growing ECs to low cell density, or in “wound molecules acting as activators and/or inhibitors of healing” experiments or perturbing cell adhesion and angiogenesis. The purpose of this review is to provide an associated molecule functions. -

Anti-ITGAE (GW21349)

3050 Spruce Street, Saint Louis, MO 63103 USA Tel: (800) 521-8956 (314) 771-5765 Fax: (800) 325-5052 (314) 771-5757 email: [email protected] Product Information Anti-ITGAE antibody produced in chicken, affinity isolated antibody Catalog Number GW21349 Formerly listed as GenWay Catalog Number 15-288-21349, Integrin alpha-E Antibody. – Storage Temperature Store at 20 °C The product is a clear, colorless solution in phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.2, containing 0.02% sodium azide. Synonyms: Integrin, alpha E (antigen CD103, human mucosal lymphocyte antigen 1; alpha polypeptide), Mucosal Species Reactivity: Human lymphocyte 1 antigen; HML-1 antigen; Integrin alpha-IEL; Tested Applications: WB CD103 antigen Recommended Dilutions: Recommended starting dilution Product Description for Western blot analysis is 1:500, for tissue or cell staining Integrin alpha-E/beta-7 is a receptor for E-cadherin. It 1:200. mediates adhesion of intra-epithelial T-lymphocytes to epithelial cell monolayers. Note: Optimal concentrations and conditions for each application should be determined by the user. NCBI Accession number: NP_002199.2 Swiss Prot Accession number: P38570 Precautions and Disclaimer This product is for R&D use only, not for drug, household, or Gene Information: Human .. ITGAE (3682) other uses. Due to the sodium azide content a material Immunogen: Recombinant protein Integrin, alpha E (anti- safety data sheet (MSDS) for this product has been sent to gen CD103, human mucosal lymphocyte antigen 1; alpha the attention of the safety officer of your institution. Please polypeptide) consult the Material Safety Data Sheet for information regarding hazards and safe handling practices. Immunogen Sequence: GI # 6007851, sequence 773 - 817 Storage/Stability For continuous use, store at 2–8 °C for up to one week. -

Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Embryo Invasion in the Mink Uterus

Placenta 75 (2019) 16–22 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Placenta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/placenta Comparative transcriptome analysis of embryo invasion in the mink uterus T ∗ Xinyan Caoa,b, , Chao Xua,b, Yufei Zhanga,b, Haijun Weia,b, Yong Liuc, Junguo Caoa,b, Weigang Zhaoa,b, Kun Baoa,b, Qiong Wua,b a Institute of Special Animal and Plant Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Changchun, China b State Key Laboratory for Molecular Biology of Special Economic Animal and Plant Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Changchun, China c Key Laboratory of Embryo Development and Reproductive Regulation of Anhui Province, College of Biological and Food Engineering, Fuyang Teachers College, Fuyang, China ABSTRACT Introduction: In mink, as many as 65% of embryos die during gestation. The causes and the mechanisms of embryonic mortality remain unclear. The purpose of our study was to examine global gene expression changes during embryo invasion in mink, and thereby to identify potential signaling pathways involved in implantation failure and early pregnancy loss. Methods: Illumina's next-generation sequencing technology (RNA-Seq) was used to analyze the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in implantation (IMs) and inter- implantation sites (inter-IMs) of uterine tissue. Results: We identified a total of 606 DEGs, including 420 up- and 186 down-regulated genes in IMs compared to inter-IMs. Gene annotation analysis indicated multiple biological pathways to be significantly enriched for DEGs, including immune response, ECM complex, cytokine activity, chemokine activity andprotein binding. The KEGG pathway including cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, Jak-STAT, TNF and the chemokine signaling pathway were the most enriched. -

Supplemental Material Annexin A2-S100A10 Represents the Regulatory Component of Maxi-Cl Channel Dependent on Protein Tyrosine De

Supplemental Material Annexin A2-S100A10 Represents the Regulatory Component of Maxi-Cl Channel Dependent on Protein Tyrosine Dephosphorylation and Intracellular Ca2+ Md. Rafiqul Islama Toshiaki Okadaa Petr G. Merzlyaka,b Abduqodir H. Toychieva,c Yuhko Ando-Akatsukad Ravshan Z. Sabirova,b Yasunobu Okadaa,e aDivision of Cell Signaling, National Institute for Physiological Sciences (NIPS), Okazaki, Japan, bInstitute of Biophysics and Biochemistry, National University of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, cDepartment of Biological Sciences, State University of New York College of Optometry, New York, NY, USA, dDepartment of Cell Physiology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Suzuka University of Medical Science, Suzuka, Japan, eDepartment of Physiology, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan Supplementary Material Supplementary Fig. 1. Maxi-Cl currents in C127 cells were unaffected by siRNA- mediated silencing of three annexin family member genes, Anxa1, Anxa3 and Anxa11. Effects of knockdown mediated by Anxa1-specific siRNA (A), Anxa3-specific siRNA (B) and Anxa11-specific siRNA (C). Top panels: The effects on expression of ANXA mRNAs in C127 cells treated with non-targeting siRNA (cnt) or Anxa1/3/11-specific siRNA (si) detected by RT-PCR using Gapdh as a control. M: molecular size markers (100-bp ladder). These data represent triplicate experiments. Upper-middle panels: Representative time courses of Maxi-Cl current activation recorded at +25 mV after patch excision from C127 cells transfected with Anxa1/3/11-specific siRNA. Lower-middle panels: Voltage- dependent inactivation pattern of Maxi-Cl currents elicited by applying single voltage step pulses from 0 to 25 and 50 mV. Bottom panels: Summary of the effects of non-targeting siRNA (Control) and Anxa1/3/11-specific siRNA on the mean Maxi-Cl currents recorded at +25 mV. -

Supp Table 1.Pdf

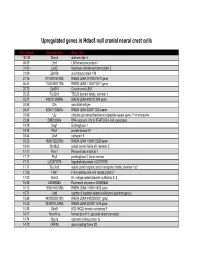

Upregulated genes in Hdac8 null cranial neural crest cells fold change Gene Symbol Gene Title 134.39 Stmn4 stathmin-like 4 46.05 Lhx1 LIM homeobox protein 1 31.45 Lect2 leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 31.09 Zfp108 zinc finger protein 108 27.74 0710007G10Rik RIKEN cDNA 0710007G10 gene 26.31 1700019O17Rik RIKEN cDNA 1700019O17 gene 25.72 Cyb561 Cytochrome b-561 25.35 Tsc22d1 TSC22 domain family, member 1 25.27 4921513I08Rik RIKEN cDNA 4921513I08 gene 24.58 Ofa oncofetal antigen 24.47 B230112I24Rik RIKEN cDNA B230112I24 gene 23.86 Uty ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat gene, Y chromosome 22.84 D8Ertd268e DNA segment, Chr 8, ERATO Doi 268, expressed 19.78 Dag1 Dystroglycan 1 19.74 Pkn1 protein kinase N1 18.64 Cts8 cathepsin 8 18.23 1500012D20Rik RIKEN cDNA 1500012D20 gene 18.09 Slc43a2 solute carrier family 43, member 2 17.17 Pcm1 Pericentriolar material 1 17.17 Prg2 proteoglycan 2, bone marrow 17.11 LOC671579 hypothetical protein LOC671579 17.11 Slco1a5 solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a5 17.02 Fbxl7 F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 7 17.02 Kcns2 K+ voltage-gated channel, subfamily S, 2 16.93 AW493845 Expressed sequence AW493845 16.12 1600014K23Rik RIKEN cDNA 1600014K23 gene 15.71 Cst8 cystatin 8 (cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic) 15.68 4922502D21Rik RIKEN cDNA 4922502D21 gene 15.32 2810011L19Rik RIKEN cDNA 2810011L19 gene 15.08 Btbd9 BTB (POZ) domain containing 9 14.77 Hoxa11os homeo box A11, opposite strand transcript 14.74 Obp1a odorant binding protein Ia 14.72 ORF28 open reading -

Supplemental Table 1. Complete Gene Lists and GO Terms from Figure 3C

Supplemental Table 1. Complete gene lists and GO terms from Figure 3C. Path 1 Genes: RP11-34P13.15, RP4-758J18.10, VWA1, CHD5, AZIN2, FOXO6, RP11-403I13.8, ARHGAP30, RGS4, LRRN2, RASSF5, SERTAD4, GJC2, RHOU, REEP1, FOXI3, SH3RF3, COL4A4, ZDHHC23, FGFR3, PPP2R2C, CTD-2031P19.4, RNF182, GRM4, PRR15, DGKI, CHMP4C, CALB1, SPAG1, KLF4, ENG, RET, GDF10, ADAMTS14, SPOCK2, MBL1P, ADAM8, LRP4-AS1, CARNS1, DGAT2, CRYAB, AP000783.1, OPCML, PLEKHG6, GDF3, EMP1, RASSF9, FAM101A, STON2, GREM1, ACTC1, CORO2B, FURIN, WFIKKN1, BAIAP3, TMC5, HS3ST4, ZFHX3, NLRP1, RASD1, CACNG4, EMILIN2, L3MBTL4, KLHL14, HMSD, RP11-849I19.1, SALL3, GADD45B, KANK3, CTC- 526N19.1, ZNF888, MMP9, BMP7, PIK3IP1, MCHR1, SYTL5, CAMK2N1, PINK1, ID3, PTPRU, MANEAL, MCOLN3, LRRC8C, NTNG1, KCNC4, RP11, 430C7.5, C1orf95, ID2-AS1, ID2, GDF7, KCNG3, RGPD8, PSD4, CCDC74B, BMPR2, KAT2B, LINC00693, ZNF654, FILIP1L, SH3TC1, CPEB2, NPFFR2, TRPC3, RP11-752L20.3, FAM198B, TLL1, CDH9, PDZD2, CHSY3, GALNT10, FOXQ1, ATXN1, ID4, COL11A2, CNR1, GTF2IP4, FZD1, PAX5, RP11-35N6.1, UNC5B, NKX1-2, FAM196A, EBF3, PRRG4, LRP4, SYT7, PLBD1, GRASP, ALX1, HIP1R, LPAR6, SLITRK6, C16orf89, RP11-491F9.1, MMP2, B3GNT9, NXPH3, TNRC6C-AS1, LDLRAD4, NOL4, SMAD7, HCN2, PDE4A, KANK2, SAMD1, EXOC3L2, IL11, EMILIN3, KCNB1, DOK5, EEF1A2, A4GALT, ADGRG2, ELF4, ABCD1 Term Count % PValue Genes regulation of pathway-restricted GDF3, SMAD7, GDF7, BMPR2, GDF10, GREM1, BMP7, LDLRAD4, SMAD protein phosphorylation 9 6.34 1.31E-08 ENG pathway-restricted SMAD protein GDF3, SMAD7, GDF7, BMPR2, GDF10, GREM1, BMP7, LDLRAD4, phosphorylation