Play — the First Name

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

2017–18 Course Catalog

Manhattan School of Music 2017–18 Course Catalog 122ND & BROADWAY | MSMNYC.EDU TABLE OF CONTENTS History of the School 4 Strings 37 Pinchas Zukerman Performance Program 39 Academic Calendar 5 Voice 40 Office of the Registrar 6 Woodwinds 42 Registration Procedures Professional Studies Certificate Program 44 Academic Regulations Dual Degree Program 45 Office of Student Accounts 7 Doctor of Musical Arts 46 Tuition and Fees Artist Diploma 49 Degree Programs and Curriculum 14 Course Descriptions 51 Departments by Major 16 Collaborative Piano 16 Brass 17 Composition 19 Conducting 21 Contemporary Performance 22 Guitar 23 Harp 25 Jazz 27 Musical Theatre 30 Orchestral Performance 31 Organ 32 Percussion 33 Piano 35 Although every effort has been made to assure the accuracy of the information in Manhattan School of Music is fully accredited by the Middle States Commission on this Catalog, students and others who use the Catalog should note laws, rules, Higher Education, the New York State Board of Regents, and the Bureau for Veterans policies, and procedures change from time to time and these changes may alter Education. the information contained in this publication. Furthermore, the School reserves its All programs listed in Departments by Major are approved for the training of vet- right, to revise, supplement, or rescind any policies, procedures or portion thereof as erans and other eligible persons by the Bureau for Veterans Education. The HEGIS described in the Catalog as it deems appropriate, at the School’s sole discretion and Code number is 1004 with the exception of the BM, MM, and DMA in Composition, without notice. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

Sendung, Sendedatum

WDR 3 Jazz & World, 25. September 2018 Das Ornette Coleman Quartet beim Enjoy Jazz Festival 2005 22:04-24.00 Uhr Stand: 17.09.2018 E-Mail: [email protected] WDR JazzRadio: http://jazz.wdr.de Moderation: Bert Noglik Redaktion: Bernd Hoffmann 22:04-24:00 Laufplan 1. Jordan K: Ornette Coleman 6:32 ORNETTE COLEMAN QUARTET Sound Grammar SG001 CD: Sound Grammar 2. Sleep Talking K: Ornette Coleman 8:55 ORNETTE COLEMAN QUARTET wie Titel 1 3. Turnaround K: Ornette Coleman 4:06 ORNETTE COLEMAN QUARTET wie Titel 1 4. Matador K: Ornette Coleman 5:55 ORNETTE COLEMAN QUARTET wie Titel 1 5. Waiting For You K: Ornette Coleman 6:50 ORNETTE COLEMAN QUARTET wie Titel 1 6. Call to Duty K: Ornette Coleman 5:34 ORNETTE COLEMAN QUARTET wie Titel 1 7. Once Only K: Ornette Coleman 9:40 ORNETTE COLEMAN QUARTET wie Titel 1 8. Song X K: Ornette Coleman 9:58 ORNETTE COLEMAN QUARTET wie Titel 1 9. The Sphinx K: Ornette Coleman 4:15 ORNETTE COLEMAN QUARTET Original Jazz Classics/ Contemporary OJCCD-163-2; LC: 00164 CD: Something Else!!! 10. Lonely Woman K: Ornette Coleman 4:58 ORNETTE COLEMAN QUINTET Atlantic 7567-81339-2; LC: 00121 CD: The Shape Of Jazz To Come 11. Blues Connotation K: Ornette Coleman 5:15 ORNETTE COLEMAN QUARTET Atlantic 7567-80767-2; LC: 00121 CD: This Is Our Music Dieses Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des WDR. 1 WDR 3 Jazz & World, 25. September 2018 Das Ornette Coleman Quartet beim Enjoy Jazz Festival 2005 22:04-24.00 Uhr Stand: 17.09.2018 E-Mail: [email protected] WDR JazzRadio: http://jazz.wdr.de 12. -

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

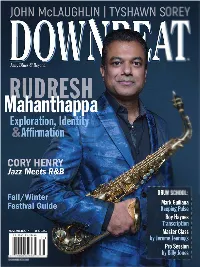

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

Institute of African American Affairs Presents PHOTO: © Bernard Benant © Bernard PHOTO

Institute of African American Affairs presents PHOTO: © Bernard Benant © Bernard PHOTO: ARTIST-IN-RESIDENCE SPRING 2016 THE PROGRAMS SATURDAY, APRIL 2, 2016 | 5:00 PM Cheikh Lô: From Mouridism to Afrobeat An evening with Cheikh Lo in conversation with Professors Mamadou Diouf and C. Daniel Dawson NYU Law School, Vanderbilt Hall - Tishman Auditorium, 1st floor Institute of African American Affairs 40 Washington Square South, NY, NY presents Cheikh Lô on his 40-year music career, his journey as a creative and spiritual soul, and the topics that provide a stage for his voice. THURSDAY, APRIL 7, 2016 | 6:00 PM Cheikh Lô and Danny Glover: ARTIST-IN-RESIDENCE Music and Pan-Africansim SPRING 2016 NYU Law School, Vanderbilt Hall - Greenberg Lounge, 1st floor 40 Washington Square South, NY, NY Danny Glover will engage Cheikh Lô in a discussion of African causes. This concert is FREE and open to the public. SATURDAY, APRIL 9, 2016 | 6:00 PM Cheikh Lô: Africa Live Concert NYU-Skirball Center for the Performing Arts 566 LaGuardia Place (corner of LaGuardia Place and Washington Square South), NY, NY Hosted by Cheikh Lô and a smaller version of his group the Ndiguel Band. THE ARTIST You must register on-line and bring your printed ticket to Skirball for admission. First come first served basis so please arrive by 5:30 pm or Cheikh Lô brings with him over forty years of making music fused with your seats may be released. Please note that the Skirball box office a variety of sounds from West and Central Africa and is one of the most will close at 6:30 pm on the day of the concert. -

Ornette Coleman and Harmolodics by Matt Lavelle

Ornette Coleman and Harmolodics by Matt Lavelle A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written and approved under the direction of Dr. Henry Martin ________________________ Newark, New Jersey May 2019 © 2019 Matt Lavelle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Ornette Coleman stands as one of the most significant innovators in jazz history. The purpose of my thesis is to show where his innovations came from, how his music functions, and how it impacted other innovators around him. I also delved into the more controversial aspects of his music. At the core of his process was a very personal philosophical and musical theory he invented which he called Harmolodics. Harmolodics was derived from the music of Charlie Parker and Coleman’s need to challenge conventional Western music theory in pursuit of providing direct links between music, nature, and humanity. To build a foundation I research Coleman’s development prior to his famous debut at the Five Spot, focusing on evidence of a direct connection to Charlie Parker. I examine his use of instruments he played other than his primary use of the alto saxophone. His relationships with the piano, guitar, and the musicians that played them are then examined. I then research his use of the bass and drums, and the musicians that played them, so vital to his music. I follow with documentation of the string quartets, woodwind ensembles, and symphonic work, much of which was never recorded. -

Program of Studies 2020

2019- 2020 PROGRAM OF STUDIES Dennis-Yarmouth Regional High School 210 Station Avenue South Yarmouth, MA 02664 Dennis-Yarmouth Regional School Committee Mrs. Jeni Landers, Chair Mr. Joseph Tierney, Vice Chair Mrs. Andrea St. Germain, Secretary Mr. Brian Carey, Treasurer Mr. James R. Dykeman, Jr. Mr. Phillip Morris Mr. Brian Sullivan District Administration Office (508) 398-7600 Mrs. Carol A. Woodbury Superintendent Mr. Kenneth T. Jenks Assistant Superintendent for Administration and Business Services Mrs. Maria Lopes Director of Pupil Services Mrs. Leila Maxwell Director of Instruction/STEM Ms. Sherry Santini Director of Instruction/Humanities & Arts Dennis-Yarmouth Regional High School Administration (508) 398-7630 Mr. G. Anthony Morrison Principal Mr. Joshua Clarkin Assistant Principal Dr. Paul A. Funk Assistant Principal/Athletic Director Ms. Jennifer A. Govoni Assistant Principal Ms. Mary B. O’Connor Assistant Principal Guidance and Counseling Department (508) 398-7650 Ms. Dale Fornoff Department Chair Ms. Annette Bowes Counselor Ms. Nicole D’Errico Counselor Mrs. Lisa Fedy School-to-Career Counselor Mrs. Kathleen Glasheen Counselor Mr. Joshua Steele Counselor Athletic Department (508) 398-7645 Dr. Paul A. Funk Athletic Director Attendance (508) 398-7655 Special Needs Department (508) 398-7649 Dr. Pamela Fee School Psychologist TABLE OF CONTENTS COURSE DESCRIPTIONS BY DEPARTMENT OR PROGRAM Alternative Learning Program ..................................................................................... .1 Applied Technology ................................................................................................... -

2007 Guelph Colloquium Speaker Bios and Abstracts

Speaker Biographies and Abstracts 2007 Guelph Jazz Colloquium Amiri Baraka, Ron Gaskin (moderator), William Parker Plenary Panel: The Future of Jazz www.williamparker.net Tamar Barzel, John Brackett and Marc Ribot Roundtable: Crisis in New Music? Vanishing Venues and the Future of Experimentalism in New York City Bios Tamar Barzel is assistant professor of Ethnomusicology at Wellesley College. Her scholarly interests center in jazz/improvisational music, Jewish cultural studies, and New York City’s downtown music scene. Her research focuses on how musicians negotiate issues of identity – cultural, national, creative, and personal – through their work. She has presented her research at national and international conferences, including the Society for Ethnomusicology, the Society for American Music, and the Center for Jazz Studies at Columbia University. Her article, “If Not Klezmer, Then What? Jewish Music and Modalities on New York City’s ‘Downtown’ Music Scene,” was published in the Michigan Quarterly Review (Winter 2002). She is working on a book manuscript, ‘Radical Jewish Culture’: Composer/Improvisers on New York City’s 1990s Downtown Scene. John Brackett is an assistant professor of Music at the University of Utah where he teaches and co-ordinates the music theory curriculum. Prof. Brackett has presented and published on the music of John Zorn, Led Zeppelin, and Arnold Schoenberg. His book – Tradition/Transgression: Critical and Analytical Essays on John Zorn’s Musical Poetics is forthcoming from Indiana University Press. Marc Ribot is a composer/guitarist based in New York City Abstracts Barzel: “Experimental Music: How Does the Centre Hold?” Brackett: “Change Has Come?: Chronicling the ‘Crisis’ on New York’s Lower East Side” Ribot: “Crisis in Indie/New Music Clubs: The rare feeding of a musical margin” Numerous clubs, venues, and other less formal performance spaces have supported and sustained many of the creative musicians who have called New York City their home. -

Harmolodic Programmes, Vol. 2012

***harmolodic programmes is an ongoing collaborative project ***about and a testament to harmolodic experience/expression ***********************in sound <> music <> vibration and life ********published in hard copy (sold for cost) and online (free). ************************we have an open call for submissions *********************of any and all relevant texts and images ********************************from anyone on the planet. ******past volumes under the title the harmolodic manifesto *************are available for download at zinelibrary.info. *******please send submissions, comments and suggestions to: ********************************[email protected]. peace <3 put forth by jean-paul larosee & billy conde goldman a f r e e s p i r i t c a n o n l y e x i s t i n a f r e e d b o d y --duncan school banner Bottlecap Press has no ownership of writings/images. all rights are reserved for the creators. 2012 B o t t l e c a p P r e s s 2 Table of Contents Cover painting by Bob Lordan and jean-paul larosee explanatory knote, the editors ************************************ page 5 o delicate vibratories…, Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka) ***************** page 6 editoreal : the harmolodic now, jean-paul larosee ****************** page 7 Black Wadada, Jeff Schlanger, musicWitness® ********************* page 10 My Approach to Playing Music, Bill Cole ************************** page 11 Music was his life…, Harry Chapin ******************************* page 21 sounds and visions, Ben Kelley and billy conde goldman ************ page 22 free-form -

Varieties of Freedom in Music Improvisation

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 781-789 Research Article Les Gillon* Varieties of Freedom in Music Improvisation https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0070 Received March 11, 2018; accepted November 16, 2018 Abstract: This article considers the freedom for the musician that exists within different kinds of music improvisation. It examines the constraints, conventions and parameters within which music improvisations are created and identifies three broad strands of improvisatory practice, that have developed in response to the development of recording technology. It argues that non-hierarchical, pan-ideomatic and structurally indeterminate forms of music improvisation that began to emerge in the late 20th century represent a form of music that models and expresses the felt freedom of the improvising musician. Keywords: music improvisation, Jazz, composition, experimental music, sound recording, freedom, Dave Brubeck, Cream, Ornette Coleman, Keith Jarrett, The Necks, Can The freedom afforded the improvising musician is often contrasted with the discipline demanded of the classical performer. As the pianist, Dave Brubeck put it, “Jazz stands for freedom. It’s supposed to be the voice of freedom: Get out there and improvise, and take chances, and don’t be a perfectionist—leave that to the classical musicians” (Duncan 1989). Although this characterisation of improvisation may tempt us to identify improvisation as an individualist activity, it is important to remember that improvisatory music is more often performed by an ensemble of improvising musicians, of which Brubeck’s own quartet was a typical example. In an ensemble, the freedom of the individual musician is not absolute. Group improvisation offers challenges to the musician and raises questions about what is meant by “freedom” within the context of collective music creation. -

Downbeat.Com September 2015 U.K. £4.00

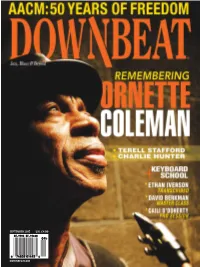

SEPTEMBER 2015 U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM September 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 9 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson,