Finance and the Fourth Dimension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Croydon OAPF Chapters 5 to 9

North End Public realm chapter contents • Existing public realm • Six principles for the public realm • Public realm strategy and its character • Funded and unfunded public realm • Play space requirements Chapter objectives • Plan for a joined up public realm network across the whole of the COA. • Plan for improvements to the quality of existing streets and spaces as per the public realm network. • Secure new streets and public spaces as per the public realm network. • Plan for the provision of quality play and informal recreation space across the Opportunity Area. • Utilise new development to help deliver this public realm network. • Utilise public funding to help deliver this public realm network. existing public realm 5.1 The quality of public realm influences a person’s 5.6 Positive aspects to be enhanced: perception of an area and determines how much time people want to spend in a place. • There are strong existing north/south routes e.g. along Wellesley Road, Roman Way, Cherry 5.2 Parts of the COA’s public realm is of poor Orchard Road, North End and High Street / South quality. This is evident in the number of barriers to End (albeit their character and quality vary) existing pedestrian and cycle movement, people’s • The Old Town, the Southern and Northern areas generally poor perception of the area, and the fact have an existing pattern of well-defined streets that 22% of streets in the COA have dead building and spaces of a human scale frontage (Space Syntax 2009). • North End is a successful pedestrianised street/ public space 5.3 Poor quality public realm is most evident around • The existing modernist building stock offers New Town and East Croydon, the Retail Core and significant redevelopment and conversion parts of Mid Croydon and Fairfield. -

PLANNING COMMITTEE AGENDA 28 April 2016 PART 6

PLANNING COMMITTEE AGENDA 28 April 2016 PART 6: Development Presentations 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 This part of the agenda is for the committee to receive presentations on proposed developments, including when they are at the pre-application stage. 1.2 Although the reports are set out in a particular order on the agenda, the Chair may reorder the agenda on the night. Therefore, if you wish to be present for a particular application, you need to be at the meeting from the beginning. 1.3 The following information and advice applies to all those reports. 2 ADVICE TO MEMBERS 2.1 These proposed developments are being reported to committee to enable members of the committee to view them at an early stage and to comment upon them. They do not constitute applications for planning permission at this stage and any comments made are provisional and subject to full consideration of any subsequent application and the comments received as a result of consultation, publicity and notification. 2.2 Members will need to pay careful attention to the probity rules around predisposition, predetermination and bias (set out in the Planning Code of Good Practice Part 5.G of the Council’s Constitution). Failure to do so may mean that the Councillor will need to withdraw from the meeting for any subsequent application when it is considered. 3 FURTHER INFORMATION 3.1 Members are informed that any relevant material received since the publication of this part of the agenda, concerning items on it, will be reported to the Committee in an Addendum Update Report. -

Whitgift CPO Inspector's Report

CPO Report to the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government by Paul Griffiths BSc(Hons) BArch IHBC an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government Date: 13 July 2015 The Town and Country Planning Act 1990 The Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1976 The Acquisition of Land Act 1981 The London Borough of Croydon (Whitgift Centre and Surrounding Land bounded by and including parts of Poplar Walk, Wellesley Road, George Street and North End) Compulsory Purchase Order 2014 Inquiry opened on 3 February 2015 Accompanied Inspection was carried out on 3 February 2015 The London Borough of Croydon (Whitgift Centre and Surrounding Land bounded by and including parts of Poplar Walk, Wellesley Road, George Street and North End) Compulsory Purchase Order 2014 File Ref: NPCU/CPO/L5240/73807 CPO Report NPCU/CPO/L5240/73807 File Ref: NPCU/CPO/L5240/73807 The London Borough of Croydon (Whitgift Centre and Surrounding Land bounded by and including parts of Poplar Walk, Wellesley Road, George Street and North End) Compulsory Purchase Order 2014 The Compulsory Purchase Order was made under section 226(1)(a) and 226(3)(a) of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, Section 13 of the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1976, and the Acquisition of Land Act 1981, by the London Borough of Croydon, on 15 April 2014. The purposes of the Order are (a) facilitating the carrying out of development, redevelopment or improvement on or in relation to the land comprising the demolition of existing -

Property Listing 27-Nov-18

Property Listing Reporting Period: 01/01/2018 to 27/11/2018 Location Property Name Head Property Operational Control Aberdeen Raiths Farm - Aberdeen Raiths Farm - Aberdeen Hammerson Union Square, Aberdeen College Street Car Park Hammerson Aberdeen College Street Railway Car Union Square, Aberdeen Hammerson Park Aberdeen Multi Storey/Surface Car Union Square, Aberdeen Hammerson Park Aberdeen Union Square Shopping Union Square, Aberdeen Hammerson Centre Aberdeen Belfast Abbey Retail Park Abbey Retail Park Hammerson Birmingham Bullring Car Park Bullring, Birmingham Hammerson Birmingham Bullring Shopping Centre Bullring, Birmingham Hammerson Birmingham Edgbaston Street Car Park Bullring, Birmingham Hammerson Birmingham LinkStreet Bullring, Birmingham Hammerson Birmingham Moor Street Car Park Bullring, Birmingham Hammerson Moor Street Car Park Birmingham Bullring, Birmingham Hammerson Retail Birmingham Moor Street Station Bullring, Birmingham Hammerson Birmingham Rotunda Retail Units Bullring, Birmingham Hammerson Grand Central Birmingham Grand Central Birmingham Hammerson Birmingham Grand Central Birmingham Grand Central Car Park Hammerson Birmingham Martineau Galleries Birmingham Dale & Century House Hammerson Offices Martineau Galleries Birmingham Londonderry House Hammerson Offices 1-3 Dale End, Kings Martineau Galleries, Birmingham Hammerson Parade Retail 4-7 Dale End, Kings Martineau Galleries, Birmingham Hammerson Parade Retail Priory Square Shopping Martineau Galleries, Birmingham Hammerson Centre Retail Bristol Cabot Circus Cabot Circus, -

London Borough of Croydon

LONDON BOROUGH OF CROYDON THE LONDON BOROUGH OF CROYDON (WHITGIFT CENTRE AND SURROUNDING LAND BOUNDED BY AND INCLUDING PARTS OF POPLAR WALK, WELLESLEY ROAD, GEORGE STREET AND NORTH END) COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER 2014 SECTION 226(1)(a) AND 226(3)(a) OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 AND SECTION 13 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT (MISCELLANEOUS PROVISIONS) ACT 1976 AND THE ACQUISITION OF LAND ACT 1981 STATEMENT OF REASONS OF THE LONDON BOROUGH OF CROYDON FOR MAKING THE COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 THE ENABLING POWERS FOR THE CPO 2 3 BACKGROUND 3 4 DESCRIPTION OF THE ORDER LAND, LOCATION AND NEW RIGHTS 6 5 CROYDON LIMITED PARTNERSHIP 12 6 DESCRIPTION OF THE SCHEME 14 7 THE COUNCIL'S PURPOSE AND JUSTIFICATION IN MAKING THE ORDER 19 8 STATUS OF ORDER LAND AND THE EXTENT TO WHICH THE SCHEME FITS WITH PLANNING FRAMEWORK 31 9 WELL-BEING OBJECTIVES AND THE COUNCIL'S SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITY STRATEGY 39 10 SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS AFFECTING THE ORDER LAND 41 11 HUMAN RIGHTS CONSIDERATIONS 41 12 EQUALITY ACT 2010 43 13 OTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION 45 15 INQUIRY PROCEDURE RULES 46 16 DOCUMENTS TO BE REFERRED TO OR PUT IN EVIDENCE IN THE EVENT OF AN INQUIRY 46 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 On 7 April 2014 the London Borough of Croydon (the "Council") resolved to make the London Borough of Croydon (Whitgift Centre and surrounding land bounded by and including parts of Poplar Walk, Wellesley Road, George Street and North End) Compulsory Purchase Order 2014 (the "Order"). The Order has been made under section 226(1)(a) of the Town -

Living at Saffron Square

Living at Saffron Square A social sustainability report commissioned by the Berkeley Group Contents Executive summary 3 This report 3 The place 3 The research 4 The residents 4 The findings 5 Recommendations 6 1. Introduction to Croydon 9 2. Saffron Square: the scheme 13 3. What is ‘social sustainability’? 17 4. Methodology 19 5. Profile of residents 23 6. RAG ratings from residents survey 29 Dimension I: Social and cultural life 29 Dimension II: Voice and influence 34 7. RAG ratings from site survey 37 Dimension III: Amenities and infrastructure 37 8. Quality of life 45 9. Conclusions and recommendations 49 References 52 Appendix A: Survey questionnaire 55 Saffron Square site map Executive summary This report This report presents the findings of LSE London’s mid-term social sustainability study of Berkeley Homes’ Saffron Square development in central Croydon. It sets out what residents said they appreciate about living at Saffron Square and what they think could be improved; it assesses the quality of design and management of the scheme; and it offers some recommendations for the future of Saffron Square and for similar developments elsewhere. The place Saffron Square is a dramatic addition to the drab cityscape of central Croydon. It consists of five podium blocks (now occupied) around a triangular landscaped plaza, as well as a striking 43-storey purple-clad tower (exterior complete but as yet unoccupied) that is visible from several miles away. The location is exceptionally good for transport, sitting almost equidistant from East and West Croydon stations and next to the tram and bus routes on busy Wellesley Road. -

Background Hilco Capital's Role Results Key Facts

www.hilcocapital.com CASE STUDY Background Founded in Croydon in 1862, Allders grew through the acquisition of other regional department stores to become a 45 store, £800 million turnover public company at its peak. The late 1990s saw a rapid decline set in and by 2005, Allders plc had been significantly loss-making for a number of years and faced administration. Lenders to the business believed their position was at risk and, believing that they were unlikely to recover a significant proportion of their loans to the company, decided to sell their secured debt positions to a consortium of investors led by Hilco Capital. Hilco Capital’s role Results • Acquired £150m of secured debt from Lehman Brothers • Innovative, proactive approach to retail administrations at substantial discount to par value enabled 30 stores and 3,500 jobs to transfer to major • Appointed by the Administrator to operate the business high street retailers during the administration • Stores continued trading throughout the transfer • Provided £15m of additional working capital to the process, maximising recoveries Administrator to extend the trading period, facilitating a • Closure process realised over £200m of inventory more orderly disposal of the business and assets • Total recoveries from the administration exceeded the • Sourced and funded an additional £20m of stock level of secured debt • Managed supplier negotiations to minimise ROT claims • Enhanced recoveries enabled a significant payment • Managed negotiations with concession operators, to be made to Allders’ pension scheme which had realising an additional £30m of sales been substantially underfunded at the time of the • Managed the smooth handover of stores to buyers administration including Debenhams, BHS and Primark Key facts £15m £20m 3,500 45 £800m working capital augment stock jobs transferred to department stores turnover provided supplied other retailers CSAL-1117 www.hilcocapital.com. -

Welcome Welcome

WELCOME Welcome to the Croydon Partnership’s public consultation. The aim of this exhibition is to provide you with an update on our plans to redevelop the Whitgift Centre and former Allders store, as well as highlighting the newly proposed improvements to the scheme. These will be captured as part of a revised outline planning application which is due to be submitted later this Summer. We are sharing our plans with you now so that your comments and feedback can be considered as the proposals are refined. Our ultimate goal remains to create an exceptional shopping and leisure destination together with new homes, which will be the centrepiece to the wider regeneration of Croydon, creating over 5,000 new jobs and attracting significant numbers of people and investment back into the town. We hope you find this exhibition useful and informative. Members of the team are here today and would be happy to answer any questions you may have. The Croydon Partnership Formed in January 2013, the Croydon Partnership is the joint venture between Westfield and Hammerson, two of the world’s leading developers and managers of shopping and leisure destinations. The two companies have combined their experience and expertise to commit to a £1.4 billion investment in the redevelopment of Croydon’s retail centre. The Croydon Partnership currently owns and manages both Whitgift and Centrale shopping centres. This means that many of the existing shops in Whitgift can move into Centrale during the redevelopment; ensuring that Croydon town centre remains a popular shopping destination throughout the building of the new scheme. -

Croydon Metropolitan Centre

The Croydon Monitoring Report Croydon Metropolitan Centre December 2012 The Croydon Local Plan aims to… Enable the development of new and refurbished office floor space in Croydon Metropolitan Centre Maintain the retail vitality and viability of Croydon Metropolitan Centre Enabling the development of new and refurbished office floor space in Croydon Metropolitan Centre Indicator 1 Target 1 Amount of vacant Class B1 Vacancy level no greater office floor space within than 12% by 2021 and no Croydon Metropolitan Centre greater than 8% by 2031 Indicator 2 Target 2 Net increase in Up to 95,000m2 new and refurbished office floor space by floor space in Croydon Metropolitan 2031 Centre Class B1 floor space The New Town area between East Croydon station and Wellesley Road is the primary office location in Croydon Metropolitan Centre Class B1 floor space There is a cluster of offices in the south of Croydon Metropolitan Centre either side of the Flyover Class B1 floor space Overall 37% of office floor space in Croydon vacancy rates Metropolitan Centre is vacant This is an increase from 2010/11 when 31% of office floor space was vacant 78 office premises are completely vacant (32% of all office premises) Croydon’s office market has been affected by the economic downturn despite its affordability compared to other parts of London Changes in Class B1 floor space in 2011/12 250000 200000 150000 100000 Croydon Local Plan target 50000 Office floor space (sq m) (sq space floor Office 0 Change in amount of Croydon New office floor space granted Metropolitan -

Table 1 1 All Interests in 47208 Square Metres of Retail and Commercial

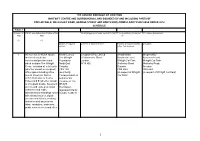

THE LONDON BOROUGH OF CROYDON (WHITGIFT CENTRE AND SURROUNDING LAND BOUNDED BY AND INCLUDING PARTS OF POPLAR WALK, WELLESLEY ROAD, GEORGE STREET AND NORTH END) COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER 2014 SCHEDULE Table 1 Number on Extent, description and situation of the Qualifying persons under section12(2)(a) of the Acquisition of Land Act 1981 - name and address Map land (3) (1) (2) Owners or reputed Lessees or reputed lessees Tenants or reputed tenants Occupiers owners (other than lessees) 1 All interests in 47208 square Martin Corney Croydon (GP2) Limited Shopmobility Shopmobility metres of retail and The Whitgift 10 Grosvenor Street Basement Level Basement Level commercial premises and Foundation London Whitgift Car Park Whitgift Car Park which includes The Whitgift North End W1K 4BJ Wellesley Road Wellesley Road Centre including all retail units Croydon Croydon Croydon (whether vacant or occupied), CR9 1SS CR0 2AG CR0 2AG office space including office (as Charity (in respect of Whitgift (in respect of Whitgift Car Park) towers known as blocks Correspondent on Car Park) A,B,C,D (known as Centre behalf of the Tower) and E (whether vacant Trustees of The or occupied) kiosks, basement Whitgift access and exits, pedestrian Foundation, entrances and malls, registered charity advertisement hoardings, sheet number 312613) advertising features, digital screens and totems, vending machines and amusement rides, escalators, staircases, public conveniences and other 1 Number on Extent, description and situation of the Qualifying persons under section12(2)(a) -

1328101765JR Bridal Brochure

Take his breath away... It has to be perfect. The one day when nothing can be left to chance. Jon Richard wants your wedding day to go as smoothly as possible. That means jewellery that works perfectly with your dress, your hair, your personality. Jewellery that catches the eye the way he caught your eye. Jewellery that takes his breath away. 2 3 Be dazzling The irresistible allure of the world’s fi nest crystals in the stunning Jon Richard Collection made with SWAROVSKI ELEMENTS. BANGLE £20 NECKLACE £20 EARRINGS £12 RING £15 TIARA £60 4 5 the purity of pearls A classic choice for your wedding day, pearls have a natural lustre and endless allure. BRACELET £20 NECKLACE £45 EARRINGS £6 HEADBAND £25 6 7 Beauty and grace As pretty as a picture, an intriguing sparkle in every crystal encrusted twist. Meet Grace.... BRACELET £20 EARRINGS £15 NECKLACE £25 CROWN COMB £25 8 9 Truly, madly, divinely Raise a glass to Vine, a collection of exquisite, delicate beauty inspired by nature. BRACELET £12 NECKLACE £20 EARRINGS £6 TIARA £35 10 11 An unforgettable vintage Recreate the glamour of the silver screen goddess with our Vintage Crystal collection. BRACELET £20 NECKLACE £28 EARRINGS £10 HEADBAND £25 12 13 ALAN HANNAH devoted Devoted to you... A collaboration with bridalwear designer Alan Hannah who produced this exclusive 26 piece collection. VINTAGE COMB £50 NECKLACE £60 CHANDELIER EARRINGS £50 VINTAGE CUFF £40 14 15 In love with Lydia... A classic combination of diamante and pearls, Lydia is an inspired choice for a glittering occasion. -

British Airways Profile

SECTION 2 - BRITISH AIRWAYS PROFILE OVERVIEW British Airways is the world's second biggest international airline, carrying more than 28 million passengers from one country to another. Also, one of the world’s longest established airlines, it has always been regarded as an industry-leader. The airline’s two main operating bases are London’s two main airports, Heathrow (the world’s biggest international airport) and Gatwick. Last year, more than 34 million people chose to fly on flights operated by British Airways. While British Airways is the world’s second largest international airline, because its US competitors carry so many passengers on domestic flights, it is the fifth biggest in overall passenger carryings (in terms of revenue passenger kilometres). During 2001/02 revenue passenger kilometres for the Group fell by 13.7 per cent, against a capacity decrease of 9.3 per cent (measured in available tonne kilometres). This resulted in Group passenger load factor of 70.4 per cent, down from 71.4 per cent the previous year. The airline also carried more than 750 tonnes of cargo last year (down 17.4 per cent on the previous year). The significant drop in both passengers and cargo carried was a reflection of the difficult trading conditions resulting from the weakening of the global economy, the impact of the foot and mouth epidemic in the UK and effects of the September 11th US terrorist attacks. An average of 61,460 staff were employed by the Group world-wide in 2001-2002, 81.0 per cent of them based in the UK.