Download Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Which Political Parties Are Standing up for Animals?

Which political parties are standing up for animals? Has a formal animal Supports Independent Supports end to welfare policy? Office of Animal Welfare? live export? Australian Labor Party (ALP) YES YES1 NO Coalition (Liberal Party & National Party) NO2 NO NO The Australian Greens YES YES YES Animal Justice Party (AJP) YES YES YES Australian Sex Party YES YES YES Pirate Party Australia YES YES NO3 Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party YES No policy YES Sustainable Australia YES No policy YES Australian Democrats YES No policy No policy 1Labor recently announced it would establish an Independent Office of Animal Welfare if elected, however its structure is still unclear. Benefits for animals would depend on how the policy was executed and whether the Office is independent of the Department of Agriculture in its operations and decision-making.. Nick Xenophon Team (NXT) NO No policy NO4 2The Coalition has no formal animal welfare policy, but since first publication of this table they have announced a plan to ban the sale of new cosmetics tested on animals. Australian Independents Party NO No policy No policy 3Pirate Party Australia policy is to “Enact a package of reforms to transform and improve the live exports industry”, including “Provid[ing] assistance for willing live animal exporters to shift to chilled/frozen meat exports.” Family First NO5 No policy No policy 4Nick Xenophon Team’s policy on live export is ‘It is important that strict controls are placed on live animal exports to ensure animals are treated in accordance with Australian animal welfare standards. However, our preference is to have Democratic Labour Party (DLP) NO No policy No policy Australian processing and the exporting of chilled meat.’ 5Family First’s Senator Bob Day’s position policy on ‘Animal Protection’ supports Senator Chris Back’s Federal ‘ag-gag’ Bill, which could result in fines or imprisonment for animal advocates who publish in-depth evidence of animal cruelty The WikiLeaks Party NO No policy No policy from factory farms. -

Right to Farm Bill 2019

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Portfolio Committee No. 4 - Industry Right to Farm Bill 2019 Ordered to be printed 21 October 2019 according to Standing Order 231 Report 41 - October 2019 i LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Right to Farm Bill 2019 New South Wales Parliamentary Library cataloguing-in-publication data: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Council. Portfolio Committee No. 4 – Industry Right to Farm Bill 2019 / Portfolio Committee No. 4 – Industry [Sydney, N.S.W.] : the Committee, 2019. [68] pages ; 30 cm. (Report no. 41 / Portfolio Committee No. 4 – Industry) “October 2019” Chair: Hon. Mark Banasiak, MLC. ISBN 9781922258984 1. New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Assembly—Right to Farm Bill 2019. 2. Trespass—Law and legislation—New South Wales. 3. Demonstrations—Law and legislation—New South Wales. I. Land use, Rural—Law and legislation—New South Wales. II. Agricultural resources—New South Wales III. Banasiak, Mark. IV. Title. V. Series: New South Wales. Parliament. Legislative Council. Portfolio Committee No. 4 – Industry. Report ; no. 41 346.944036 (DDC22) ii Report 41 - October 2019 PORTFOLIO COMMITTEE NO. 4 - INDUSTRY Table of contents Terms of reference iv Committee details v Chair’s foreword vi Finding vii Recommendation viii Conduct of inquiry ix Chapter 1 Overview 1 Reference 1 Background and purpose of the bill 1 Overview of the bill's provisions 2 Chapter 2 Key issues 5 Nuisance claims 5 Balancing the rights of farmers and neighbours 5 Deterring nuisance claims 8 The nuisance shield: a defence or bar to a claim? 9 Remedies for nuisance -

(Agricultural Protection) Bill 2019 Submission

SENATE LEGAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS LEGISLATION COMMITTEE Criminal Code Amendment (Agricultural Protection) Bill 2019 Submission My farming background The community is increasingly aware of farming practices – but wants to know more Key reasons why I oppose the bill Why is farm trespass happening? Productivity Commission – Regulation of Agriculture final report 2016 Erosion of community trust Biosecurity First World countries’ view of our farming practices Futureye Report – Australia’s Shifting Mind Set on Farm Animal Welfare The major new trend – plant-based food and lab meat Ag-gag laws Who are these animal activists? Conclusion Attachment – additional references regarding Ag-gag laws 1 Thank you for the opportunity of making a submission. My farming backgrond Until the age of 35, I experienced life on a dairy and beef farm in northern Victoria. In the 1960s I used to accompany our local vet on his farm rounds, because I wanted to study veterinary science. I saw all sorts of farming practices first-hand. I saw the distress of calves having their horn buds destroyed with hot iron cautery. I saw the de-horning of older cattle. I saw the castration of young animals by burdizzo. All these procedures took place without pain relief. I saw five-day old bobby calves put on trucks destined for the abattoir. I heard cows bellowing for days after their calves were taken. One Saturday I saw sheep in an abattoir holding pen in 40- degree heat without shade as they awaited their slaughter the following Monday. These images have remained with me. The community is increasingly aware of farming practices – but wants to know more Nowadays pain relief is readily available for castration, mulesing etc, but it is often not used because of its cost to farmers. -

Which Political Parties Are Standing up for Animals?

Which political parties are standing up for animals? Has a formal animal Supports Independent Supports end to welfare policy? Office of Animal Welfare? live export? Australian Labor Party (ALP) YES YES1 NO Coalition (Liberal Party & National Party) NO2 NO NO The Australian Greens YES YES YES Animal Justice Party (AJP) YES YES YES Australian Sex Party YES YES YES Health Australia Party YES YES YES Science Party YES YES YES3 Pirate Party Australia YES YES NO4 Derryn Hinch’s Justice Party YES No policy YES Sustainable Australia YES No policy YES 1Labor recently announced it would establish an Independent Office of Animal Welfare if elected, however its struc- ture is still unclear. Benefits for animals would depend on how the policy was executed and whether the Office is independent of the Department of Agriculture in its operations and decision-making. Australian Democrats YES No policy No policy 2The Coalition has no formal animal welfare policy, but since first publication of this table they have announced a plan to ban the sale of new cosmetics tested on animals. Nick Xenophon Team (NXT) NO No policy NO5 3The Science Party's policy states "We believe the heavily documented accounts of animal suffering justify an end to the current system of live export, and necessitate substantive changes if it is to continue." Australian Independents Party NO No policy No policy 4Pirate Party Australia policy is to “Enact a package of reforms to transform and improve the live exports industry”, including “Provid[ing] assistance for willing live animal exporters to shift to chilled/frozen meat exports.” 6 Family First NO No policy No policy 5Nick Xenophon Team’s policy on live export is ‘It is important that strict controls are placed on live animal exports to ensure animals are treated in accordance with Australian animal welfare standards. -

Criminal Code Amendment (Animal Protection) Bill 2015

The Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Legislation Committee Criminal Code Amendment (Animal Protection) Bill 2015 June 2015 © Commonwealth of Australia 2015 ISBN 978-1-76010-195-4 This document was prepared by the Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. Membership of the committee Members Senator the Hon Bill Heffernan, Chair New South Wales, LP Senator Glenn Sterle, Deputy Chair Western Australia, ALP Senator Joe Bullock Western Australia, ALP Senator Sean Edwards South Australia, LP Senator Rachel Siewert Western Australia, AG Senator John Williams New South Wales, NATS Substitute members for this inquiry Senator Lee Rhiannon New South Wales, AG to replace Senator Rachel Siewert Other Senators participating in this inquiry Senator Chris Back Western Australia, LP Senator David Leyonhjelm New South Wales, LDP Senator Nick Xenophon South Australia, IND iii Secretariat Mr Tim Watling, Secretary Dr Jane Thomson, Principal Research Officer Ms Erin East, Principal Research Officer Ms Bonnie Allan, Principal Research Officer Ms Trish Carling, Senior Research Officer Ms Kate Campbell, Research Officer Ms Lauren Carnevale, Administrative Officer PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Ph: 02 6277 3511 Fax: 02 6277 5811 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.aph.gov.au/senate_rrat iv Table of contents Membership of the committee ........................................................................ -

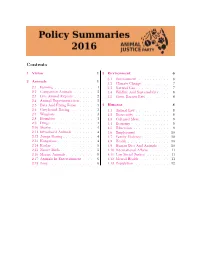

AJP Policy Summary

Contents 1 Vision 1 3 Environment 6 3.1 Environment ........... 6 2 Animals 1 3.2 Climate Change .......... 7 2.1 Farming .............. 1 3.3 Natural Gas ............ 7 2.2 Companion Animals . 2 3.4 Wildlife And Sustainability . 8 2.3 Live Animal Exports . 2 3.5 Great Barrier Reef . 8 2.4 Animal Experimentation . 2 2.5 Bats And Flying Foxes . 3 4 Humans 8 2.6 Greyhound Racing . 3 4.1 Animal Law ............ 8 2.7 Wombats ............. 3 4.2 Biosecurity ............ 8 2.8 Brumbies ............. 3 4.3 Cultured Meat .......... 9 2.9 Dingo ............... 4 4.4 Economy ............. 9 2.10 Sharks ............... 4 4.5 Education ............. 9 2.11 Introduced Animals . 4 4.6 Employment . 10 2.12 Jumps Racing ........... 4 4.7 Family Violence . 10 2.13 Kangaroos ............. 4 4.8 Health . 10 2.14 Koalas ............... 5 4.9 Human Diet And Animals . 10 2.15 Native Birds ............ 5 4.10 International Affairs . 11 2.16 Marine Animals .......... 5 4.11 Law Social Justice . 11 2.17 Animals In Entertainment . 6 4.12 Mental Health . 11 2.18 Zoos ................ 6 4.13 Population . 12 . Introduction This is a compendium of new policy Summaries and Key Objectives flowing out of the work of various policy committees during 2016. Editing has been made in an attempt to ensure consistency of style and to remove detail which is considered unnecessary at this stage of our development as a political party. Policy development is an on-going process. If you have comments, criticisms or sugges- tions on policy please email [email protected]. -

Animal Justice Party

Poultry Public Consultation Animal Justice Party February 2018 Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 3 2 IS THIS CONSULTATION BEING DONE IN GOOD faith?3 3 Biased REPRESENTATION AND PROCESSES4 4 Misuse OR NEGLECT OF SCIENTIfiC EVIDENCE5 4.1 ReferENCES........................................6 5 GenerAL COMMENTS ON THE RIS AND StandarDS7 6 Poultry AT SLAUGHTERING ESTABLISHMENTS (Part A, 11)7 6.1 SpecifiC RECOMMENDATIONS..............................8 6.2 Why LIVE SHACKLING SHOULD BE PHASED OUT......................9 6.3 PrOBLEMS WITH THE SHACKLING PROCESS........................ 10 6.4 PrOBLEMS WITH ELECTRICAL STUNNING.......................... 11 6.5 End-of-lay HENS..................................... 11 6.6 ReferENCES........................................ 12 1 7 Laying ChickENS (Part B, 1) 14 7.1 WELFARE.......................................... 14 7.2 Cages AND WELFARE OF ‘Layer Hens’ .......................... 15 7.3 Public Attitudes TO INDUSTRIALISING Animals..................... 15 7.4 The Cost OF WELFARE................................... 16 7.5 IN Conclusion...................................... 16 7.6 ReferENCES........................................ 16 8 Meat ChickENS (Part B, 2) 17 8.1 Lameness........................................ 18 8.2 Contact DERMATITIS................................... 20 8.3 Recommendations................................... 20 8.4 ReferENCES........................................ 21 9 Ducks (Part B, 4) 24 9.1 ReferENCES........................................ 26 2 1 INTRODUCTION This SUBMISSION IS IN RESPONSE TO -

WP05 Steven Van Hauwaert ESR Final Report

SEVENTH FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME THE PEOPLE PROGRAMME MARIE CURIE ACTIONS – NETWORKS FOR INITIAL TRAINING (ITN) ELECDEM TRAINING NETWORK IN ELECTORAL DEMOCRACY GRANT AGREEMENT NUMBER: 238607 Deliverable D5.1 – Institutional Structures and Partisan Attachments Final Report Early Stage Research fellow (ESR) Steven Van Hauwaert Host Institution University of Vienna, Austria The ELECDEM project was funded by the FP7 People Programme ELECDEM 238607 A. ABSTRACT The academic literature proposes a wide variety of factors that contribute to the explanation of far right party development. However, these constructs are typically structural in nature, rather variable-oriented and are not necessarily able to explain far right party development as a whole. Much too often, the existing literature assumes far right parties develop independently from one another, even though processes such as globalisation make this highly unlikely. Therefore, this study refutes this assumption and claims far right party development is much more interdependent than the literature describes. To do so, this study proposes to complement existing explanatory frameworks by shifting its principal focus and emphasising more dynamic variables and processes. This innovative study’s main objective is to bring time and agency back into the analysis, thereby complementing existing frameworks. In other words, the timing and the pace of far right party development should be considered when explaining this phenomenon, just like it should include the far right party itself. Largely based on social movement and policy diffusion literature, this study identifies, describes and analyses the different facets and the importance of diffusion dynamics in the development of West-European far right parties. The focus on the similarities and differences of diffusion patterns and the ensuing consequences for far right party development, allows this study to explore the nature, the role and the extent of diffusion dynamics in the development of West-European far right parties. -

![Review] a Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015 Gonzalo Villanueva, a Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4735/review-a-transnational-history-of-the-australian-animal-movement-1970-2015-gonzalo-villanueva-a-transnational-history-of-the-australian-animal-movement-1970-2015-1584735.webp)

Review] a Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015 Gonzalo Villanueva, a Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015

Animal Studies Journal Volume 7 Number 1 Article 16 2018 [Review] A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015 Gonzalo Villanueva, A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015 Christine Townend Animal Liberation, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj Part of the Art and Design Commons, Australian Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Education Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Philosophy Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Townend, Christine, [Review] A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015 Gonzalo Villanueva, A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015, Animal Studies Journal, 7(1), 2018, 322-326. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol7/iss1/16 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] [Review] A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015 Gonzalo Villanueva, A Transnational History of the Australian Animal Movement, 1970-2015 Abstract This is a book that every student of politics would enjoy reading, and indeed should read, together with every person who wishes to become an activist (not necessarily an animal activist). This is because the book discusses, in a very interesting and exacting analysis, different strategies used to achieve a goal; in this case, the liberation of animals from the bonds of torture, deprivation and cruelty. Gonzalo Villanueva clearly has compassion for animals, but he is careful to keep an academic distance in this thoroughly researched, scholarly book, which is nevertheless easy to read. -

AJP Submission on Dairy Inquiry

1 This is the Animal Justice Party’s submission to the Australian government’s senate committee inquiry into Australia’s dairy crisis. The inquiry’s terms of reference include establishing a fair and long-term solution to Australia’s dairy crisis with particular reference to milk security. There are several fundamental reasons why the very focus of the inquiry is significantly flawed. They include: 1. The extreme animal cruelty issues involved in the dairy industry 2. The harmful effects to human health caused by the consumption of dairy 3. The environmental harm caused by the dairy industry and its fundamentally unsustainable nature People are turning away from dairy in droves largely as a result of the above reasons along with increased awareness. Considering the facts and science about dairy, as will be reviewed in more detail below, it is clear that the most responsible course of action for the government to take, is to transition away from animal-based milk and dairy, to humane, healthy, and sustainable plant-based milks. Instead of focussing on trying to rescue an unsustainable industry that is harmful to humans and animals, the government should be turning its attention to innovative transition solutions. Consumers are increasingly embracing plant-based milks and it is the position of the Animal Justice Party that the government should embrace this trend and promote plant-based milks as healthier, more humane and more sustainable industries. 1. Animal Cruelty Dairy cows have been genetically manipulated through selective breeding to produce around 35-50 litres of milk per day, which is around 10 times more than calves would need if they were allowed to suckle from their mother (Dairy Australia, 2014). -

Inquiry Into the Problem of Feral and Domestic Cats in Australia

Committee Secretariat PO Box 6021 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Submission: Inquiry into the problem of feral and domestic cats in Australia This submission has been prepared by the national submissions working group within the Animal Justice Party (‘the AJP'). The working group makes this submission on behalf of the AJP with the approval and the endorsement of the Board of Directors. The AJP was established to promote and protect the interests and capabilities of animals by providing a dedicated voice for them in Australia’s political system, whether they are domestic, farmed or wild. The AJP seeks to restore the balance between humans, animals and nature, acknowledge the interconnectedness and interdependence of all species, and respect the wellbeing of animals and the environment alongside that of humans and human societies. The AJP advocates for all animals and the natural environment through our political and democratic institutions of government. Above all, the AJP seeks to foster consideration, respect, kindness and compassion for all species as core values in the way in which governments design and deliver initiatives and the manner in which they function. The following submission is underpinned by these fundamental beliefs. The AJP has policies on Companion Animals and Introduced Animals. This submission puts forward commentary in line with these policies. 1 THE SUBMISSION The AJP acknowledges that non-native animal species, introduced to Australia by people for varying activities, are modifying the environment, competing with native species and contributing to biodiversity loss and ecosystem decline. These activities include shooting, hunting and fishing (e.g. rabbits, foxes, deer, European carp), animal agriculture (e.g. -

Safe Ireland the Lawlessness of the Home

The lawlessness of the home Women’s experiences of seeking legal remedies to domestic violence and abuse in the Irish legal system 2014 Contents Acknowledgements 2 Prologue 3 Rationale for the study 7 Current context: the enormity of the problem 7 The Irish legal system and domestic violence 9 Critique of the Domestic Violence Act 1996 – 2002 10 What about the children? 11 Government obligations and policy context 13 Other institutional policies 14 An Garda Síochána 15 The Probation Service 15 International policies responding to domestic violence 16 Challenges to seeing the gendered nature of domestic violence 19 Research methodology 21 Why use first-person narratives? 21 The desk-based research 24 The interviews 24 Language 26 Narratives of women who have experienced abuse, violence and the legal system 27 1. The right to be heard 28 2. The consequences of the court not hearing the evidence. High-risk factors: the case of cruelty to animals 37 - The importance of assessing risk 40 3. Consistency and continuity in the application of the law 41 - An analysis of specialist domestic violence court models 48 4. The victim and perpetrator stereotypes 53 - Anti-essentialism and the dangers of the stereotype 56 5. The importance of good advocacy, expertise and policing 59 6. The need for a legal definition of domestic abuse and violence 72 - Definitions of domestic violence around the world 74 7. Why she doesn’t just leave – the barriers to safety and help-seeking 77 8. The dangers of a fragmented system – the continued case for a multi-agency approach 80 ‘The lawlessness of the home’ Women’s experiences of seeking legal remedies to domestic violence and abuse in the Irish legal system 1 Conclusions on domestic violence and the role of the legal system 87 The rule of law 88 Agency and autonomy 89 The legal system’s failure 90 What we at SAFE Ireland propose to do next 91 Closing address 92 Recommendations 94 Notes 98 Bibliography 104 Acknowledgements SAFE Ireland is pleased to present this important research report.