America and the 'Way to the Devil'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper XVII. Unit 1 Nathaniel Hawthorne's the Scarlet Letter 1

Paper XVII. Unit 1 Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter 1. Introduction 1.1 Objectives 1.2 Biographical Sketch of Nathaniel Hawthorne 1.3 Major works of Hawthorne 1.4 Themes and outlines of Hawthorne’s novels 1.5 Styles and Techniques used by Hawthorne 2. Themes, Symbols and Structure of The Scarlet Letter 2.1 Detailed Storyline 2.2 Structure of The Scarlet Letter 2.3 Themes 2.3.1 Sin, Rejection and Redemption 2.3.2 Identity and Society. 2.3.3 The Nature of Evil. 2.4 Symbols 2.4.1 The letter A 2.4.2 The Meteor 2.4.3 Darkness and Light 3. Character List 3.1 Major characters 3.1.1 Hester Prynn 3.1.2 Roger Chillingworth 3.1.3 Arthur Dimmesdale 3.2 Minor Characters 3.2.1 Pearl 3.2.2 The unnamed Narrator 3.2.3 Mistress Hibbins 3.2.4 Governor Bellingham 4. Hawthorne’s contribution to American Literature 5. Questions 6. Further Readings of Hawthorne 1. Introduction 1.1 Objectives This Unit provides a biographical sketch of Nathaniel Hawthorne first. Then a list of his major works, their themes and outlines. It also includes a detailed discussion about the styles and techniques used by him. The themes, symbols and the structure of The Scarlet Letter are discussed next, followed by the list of major as well as minor characters. This unit concludes with a discussion about Hawthorne’s contribution to American literature and a set of questions. Lastly there is a list of further readings of Hawthorne to gain knowledge about the critical aspects of the novel. -

Views on Economic Issues, M

1 FOR THE COLLECTION OF A LIFETIME The process of creating one’s personal library is the pursuit of a lifetime. It requires special thought and consideration. Each book represents a piece of history, and it is a remarkable task to assemble these individual items into a collection. Our aim at Raptis Rare Books is to render tailored, individualized service to help you achieve your goals. We specialize in working with private collectors with a specific wish list, helping individuals find the ideal gift for special occasions, and partnering with representatives of institutions. We are here to assist you in your pursuit. Thank you for letting us be your guide in bringing the library of your imagination to reality. OUR GUARANTEE All items are fully guaranteed and can be returned within ten days. We accept all major credit cards and offer free domestic shipping and free worldwide shipping on orders over $500 for single item orders. A wide range of rushed shipping options are also available at cost. Each purchase is expertly packaged to ensure safe arrival and free gift wrapping services are available upon request. FOR MORE INFORMATION For further details regarding any of the items featured in this catalog, visit our website or call 561-508-3479 for expert assistance from one of our booksellers. www.RaptisRareBooks.com Raptis Rare Books | 226 Worth Avenue | Palm Beach, FL 33480 T. 561-508-3479 | F. 561-757-7032 | [email protected] 2 Contents Americana 2 Philosophy & Religion 14 History & World Leaders 28 Literature 40 Art, Illustration & Photography 94 Children’s Literature 98 Sports & Leisure 104 Travel & Exploration 110 Economic & Social Theory 114 Index 126 4 Americana RARE PHOTOGRAPHIC PORTRAIT OF ROBERT E. -

VCU Open 2013 Round #7

VCU Open 2013 Round 7 Tossups 1. One play by this author features a man with "all the nations of the old world at war in his veins" arriving to sort out the plot in the final act; that character created by him is the American naval captain Hamlin Kearney. This author wrote a play that includes a Moroccan sheikh who kills Christians until stopped by the lady-explorer Cicely Waynflete and the crusty title guide. In another play by this man, Essie is invited to stay in the new home of a man that Judith Anderson hates, after uncle Peter is hanged, and Westerbridge, New Hampshire is sent into a tizzy when Dick Dudgeon is sentenced to death. In another play by him, a chain of murders leads to the death of Pothinus and then, at the hands of Rufio, Ftatateeta, after one title character finds the other between the paws of the Sphinx and then in a rolled-up carpet. This author of Captain Brassbound's Conversion included John Burgoyne as an antagonist in his The Devil's Disciple; those two dramas, along with Caesar and Cleopatra, make up his Three Plays for Puritans. For 10 points, name this playwright of Man and Superman and Pygmalion. ANSWER: George Bernard Shaw [or GBS] 019-13-64-07101 2. Magallis and Damophilus of Enna are particularly blamed for behavior leading to an event of this type by Diodorus Siculus. One of these events was organized by a Syrian man who had entertained party guests by breathing fire and making humorous prophecies about an event of this kind. -

Library Builders

LIBRARY BUILDERS COLLECTIONS Story Collections Big Book of Beginner Books (K-3) The Beginner Books series Nursery Rhyme Collections Make Way for McCloskey: Robert McCloskey has delighted early readers Treasury (PK-3) for over fifty years. These My Book House - In the Nursery (PK-AD) From Make Way for Ducklings to Blueberries fun stories have the perfect This book is a reprint of what was once Volume for Sal, this hardcover volume contains eight of blend of words and pictures 1 of the My Book House series published Robert McCloskey’s acclaimed children’s books. to encourage kids to read all in 1937. This wonderful collection of nursery Stories in this collection include Make Way for by themselves. They make rhymes was gathered from all over the world. Ducklings; Blueberries for Sal; The Doughnuts great read-alouds, too! Each More than 350 nursery rhymes and children’s from Homer Price; Burt Dow, Deep-Water Man; hardcover book contains poems are featured with colored and/or black Lentil; Ever So Much More So from Centerburg the complete text and art- and white illustrations that remind me of the old Tales; Time of Wonder; and One Morning in work of six individual Beginner Books titles, all “Dick and Jane” style of pictures. This book is Maine. These classic stories contain the original packaged into one convenient, money-saving vol- an unabridged reprint and includes Japanese lul- text and artwork, and biographical informa- ume. Except where noted, each volume features labies, native American songs, Russian rhymes, tion provides insight into McCloskey’s enduring books by a variety of authors and/or illustrators. -

Rare Books, Autographs & Maps

RARE BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHS & MAPS Tuesday, November 13, 2018 NEW YORK RARE BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHS & MAPS AUCTION Tuesday, November 13, 2018 at 10am EXHIBITION Saturday, November 10, 10am – 5pm Sunday, November 11, Noon – 5pm Monday, November 12, 10am – 6pm LOCATION Doyle 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com CONTENTS Original Illustration Art 1-11 Original Art by Kahlil Gibran 12-16 Original Art & Artist’s Books 17-34 INCLUDING PROPERTY Autographs 35-59 FROM THE ESTATES OF Aviation & Travel 60-68 Edgar Dannenberg, New York, New York Atlases & Map 69-84 Hilda U. and Rudolph Forchheimer Color Plate & Illustrated Books 85-94 Albert H. Gordon, New York, New York Fine Bindings 95-99 Henry Hives Manuscripts & Early Printing 100-107 Sidney B. Jacques 19th Century Literature & Autographs 108-147 Arnold ‘Jake’ Johnson 20th Century Literature & Autographs 148-238 Lucille and Charles Plotz Printed & Manuscript Americana 239-286 The Collection of Rudolf Serkin Sheldon Tannen SELECTIONS FROM THE LIBRARY OF The Wynant D. Vanderpoel Trust ARNOLD “JAKE” JOHNSON Barbara Wainscott Americana 287-327 Angling Books 328-371 Color Plate 372-385 Miscellaneous Hunting, Sporting & INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM Derrydale Press 386-396 A Private Collector Travel, Big Game & Sporting Books A Private New Jersey Collection relating to Africa, Asia & India 397-462 A New York Collector A Private New York Collector Glossary I A Southern California Historian Conditions of Sale II Terms of Guarantee IV Information on Sales & Use Tax V Buying at Doyle VI Selling at Doyle VIII Auction Schedule IX Company Directory XI Absentee Bid Form XII Lot 71 Original Illustration Art 1 ADDAMS, CHARLES (1912-1988) Dear Dead Days, 1959. -

A Literary Nightmare" (1876) About:Reader?Url=

Mark Twain, "A Literary Nightmare" (1876) about:reader?url=https://acephalous.typepad.com/acephalous/m... acephalous.typepad.com Mark Twain, "A Literary Nightmare" (1876) 10-13 minutes Will the reader please to cast his eye over the following lines, and see if he can discover anything harmful in them? Conductor, when you receive a fare, Punch in the presence of the passenjare! A blue trip slip for an eight-cent fare, A buff trip slip for a six-cent fare, 1 of 20 17/01/20, 8:34 am Mark Twain, "A Literary Nightmare" (1876) about:reader?url=https://acephalous.typepad.com/acephalous/m... A pink trip slip for a three-cent fare, Punch in the presence of the passenjare! CHORUS Punch, brothers! punch with care! Punch in the presence of the passenjare! I came across these jingling rhymes in a newspaper, a little while ago, and read them a couple of times. They took instant and entire possession of me. All through breakfast they went waltzing through my brain; and when, at last, I rolled up my napkin, I could not tell whether I had eaten anything or not. I had carefully laid out my 2 of 20 17/01/20, 8:34 am Mark Twain, "A Literary Nightmare" (1876) about:reader?url=https://acephalous.typepad.com/acephalous/m... day's work the day before—thrilling tragedy in the novel which I am writing. I went to my den to begin my deed of blood. I took up my pen, but all I could get it to say was, "Punch in the presence of the passenjare." I fought hard for an hour, but it was useless. -

Literary Analysis Copyright © 2014 Notgrass Company

EXPLORING AMERICA LITERARY ANALYSIS Copyright © 2014 Notgrass Company. All rights reserved. You may print copies of this material for your family, but you may not redistribute it without permission from the publisher. Designed for use with Exploring America by Ray Notgrass Notgrass Company 975 Roaring River Rd. Gainesboro, TN 38562 1-800-211-8793 www.notgrass.com Who, What, How, Why, and Why Not: A Primer for Literary Analysis of Fiction People read books. Some books (think Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, and Jane Austen) are still widely read decades and even centuries after they were written. Many, many books (think of the highly forgettable ones you see in used book sales—over and over) are a flash in the pan or are even less noticeable. What’s the difference? Is it just that most people like this book and most people dislike that one? Sort of, but it is more nuanced than that. Literary analysis is studying the parts of a work of literature (such as plot, setting, characters, and narration) to see how the author uses them to create the overall meaning of the work as a whole. Professors, teachers, students, critics, and everyday people analyze works of literature: novels, short stories, poems, and non-fiction. They think about the story or plot of the book, how it develops, the characters in the book, the words and structure that the author uses, and other elements of the work. People who analyze literature have developed standard methods. Primarily, this involves looking for elements that are found in most literary works. The purpose of literary analysis is to understand how a piece of literature works: how the writer constructs his or her story, and why the work affects readers the way it does. -

Context I Traducció Comentada De Letters from the Earth De Mark Twain

CONTEXT I TRADUCCIÓ COMENTADA DE LETTERS FROM THE EARTH DE MARK TWAIN 101486 – Treball de Fi de Grau Grau en Traducció i Interpretació Curs acadèmic 2014-2015 Estudiant: Raquel Castaño Clariana Tutor: Dolors Udina Abelló 8 de juny de 2015 Facultat de Traducció i d’Interpretació Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Dades del TFG Títol: Context i traducció comentada de Letters from the Earth de Mark Twain. Autor: Raquel Castaño Clariana Tutor: Dolors Udina Abelló Centre: Facultat de Traducció i d'Interpretació Estudis: Grau en Traducció i Interpretació Curs acadèmic: 2014-15 Paraules clau Mark Twain, traducció, religió, cristianisme, sarcasme, crítica, Bíblia. Resum/Summary En aquest treball es presenta la figura de Mark Twain i la seva obra, la major part de la qual no està traduïda al català. Seguidament, se centra en el seu pensament religiós. Twain fou una persona molt crítica amb la religió, especialment amb el cristianisme, com queda palès en l’obra Letters from the Earth. En aquest treball es fa una proposta de traducció d’aquest conjunt d’assajos en forma de carta al català, justificant les decisions preses. This academic work presents the figure of Mark Twain and his writing, most of which has not been translated into Catalan. After that, it focuses on his views on religion. Twain was very critical of religion, especially of Christianity, as clearly stated in his work Letters from the Earth. This project consists of a draft translation of this series of essays in letter form into Catalan, explaining the decisions taken throughout the process. Avís legal/Legal notice © Raquel Castaño Clariana, Terrassa, 2015. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Including Recent Acquisitions And Items In Only Tangentially Related Fields. Catalogue 368 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.williamreesecompany.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are considered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and Fax for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Three Very Short Poems: The Verbal Economics of Twentieth-Century American Poetry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/23q9t3c3 Author Schmidt, Jeremy Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Three Very Short Poems: The Verbal Economics of Twentieth-Century American Poetry A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Jeremy A. Schmidt 2020 © Copyright by Jeremy A. Schmidt 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Three Very Short Poems: The Verbal Economics of Twentieth-Century American Poetry by Jeremy A. Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor Michael North, Chair This study examines three very short poems from three distinct moments in recent literary history in order to determine the limits of the poetic virtue of concision and to consider the social and aesthetic issues raised by extreme textual reduction. Attending to the production, circulation, and afterlives of Ezra Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro” (1913), Gwendolyn Brooks’s “We Real Cool” (1959), and Aram Saroyan’s “lighght” (1966), I argue that such texts necessarily, and yet paradoxically, join simplicity and ease to difficulty and effort. Those tense combinations, in turn, make these poems ideal sites for examining how brevity functions as a shared resource through which writers define and redefine what constitutes poetic labor and thus negotiate their individual relationships to the poetic tradition. In tracing those negotiations, Three Very Short Poems: The Verbal Economics of Twentieth-Century American Poetry participates in the ongoing reassessment of the relationship between literary modernism and mass culture by ii foregrounding art-poems that have reached unusual levels of popularity. -

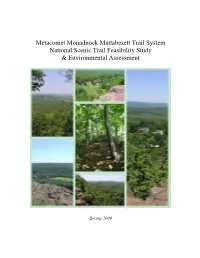

Metacomet Monadnock Mattabesett Trail System National Scenic Trail Feasibility Study and Environmental Assessment

Metacomet Monadnock Mattabesett Trail System National Scenic Trail Feasibility Study & Environmental Assessment Spring 2006 Metacomet Monadnock Mattabesett Trail System National Scenic Trail Feasibility Study and Environmental Assessment Final Report – January 2007 Massachusetts/Connecticut National Park Service, Northeast Region: Project Manager, Jamie Fosburgh Project Leader, Connecticut: Kevin Case Project Assistant, Connecticut: Dan Hubbard Project Leaders, Massachusetts: Christopher Curtis, Pioneer Valley Planning Commission (PVPC) Peggy Sloan, Franklin Regional Council of Governments (FRCOG) Project Staff, Massachusetts: Jessica Allan, PVPC Jessica Atwood, FRCOG Eliot Brown, FRCOG Anne Capra, PVPC Raphael Centeno, PVPC Ryan Clary, FRCOG Matt Delmonte, PVPC Beth Gianinni, FRCOG Shaun Hayes, PVPC Sigrid Hughes, FRCOG Gretchen Johnson, FRCOG Bill Labich, FRCOG Jim Scace, PVPC Heather Vinsky, PVPC Tracy Zafian, FRCOG Todd Zukowski, PVPC All cover photos and interior photos for Massachusetts by Christopher Curtis and for Connecticut by Robert Pagini and Connecticut Forests and Parks Association For further information, or to comment on this report, please contact: MMM Trail National Scenic Trail Feasibility Study National Park Service, Northeast Region 15 State Street Boston, MA 02109 617- 223- 5051 West Peak, Connecticut Contents Summary of Findings 1 Trail System Issues and Trail System Background 1 Opportunities 43 Study Accomplishments 2 A. Trail Use 43 Important Spin-Offs of the Study 2 B. Trail Protection 43 C. Landowner Issues/Interests 45 Introduction and Study D. Maintenance and Trail Management Background 5 Related Issues 46 E. Administration 46 ASummary of National Trails System Act 5 F. Community Connections 47 B. Background on Metacomet Monadnock- G. Trail Continuity and Relocations 47 Mattabesett Trail Study 5 H.