Evidence from Covid-19 Pandemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19 International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

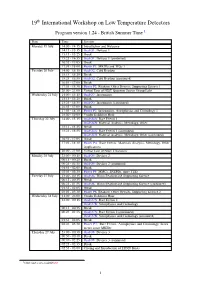

19th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Program version 1.24 - British Summer Time 1 Date Time Session Monday 19 July 14:00 - 14:15 Introduction and Welcome 14:15 - 15:15 Oral O1: Devices 1 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O1: Devices 1 (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:00 Poster P1: MKIDs and TESs 1 Tuesday 20 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O2: Cold Readout 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O2: Cold Readout (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P2: Readout, Other Devices, Supporting Science 1 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Quantum Sensor Group Labs Wednesday 21 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O3: Instruments 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O3: Instruments (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P3: Instruments, Astrophysics and Cosmology 1 18:00 - 19:00 Vendor Exhibitor Hour Thursday 22 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 (continued) Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P4: Rare Events, Materials Analysis, Metrology, Other Applications 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Cleanoom Monday 26 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O5: Devices 2 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O5: Devices 2 (continued) 01:55 - 02:05 Break 02:05 - 03:30 Poster P5: MMCs, SNSPDs, more TESs Tuesday 27 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science -

Estimating the Overdispersion in COVID

Wellcome Open Research 2020, 5:67 Last updated: 13 JUL 2020 RESEARCH ARTICLE Estimating the overdispersion in COVID-19 transmission using outbreak sizes outside China [version 3; peer review: 2 approved] Akira Endo 1,2, Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group, Sam Abbott 1,3, Adam J. Kucharski1,3, Sebastian Funk 1,3 1Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, WC1E 7HT, UK 2The Alan Turing Institute, London, NW1 2DB, UK 3Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, WC1E 7HT, UK First published: 09 Apr 2020, 5:67 Open Peer Review v3 https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15842.1 Second version: 03 Jul 2020, 5:67 https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15842.2 Reviewer Status Latest published: 10 Jul 2020, 5:67 https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15842.3 Invited Reviewers 1 2 Abstract Background: A novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak has now version 3 spread to a number of countries worldwide. While sustained transmission (revision) report chains of human-to-human transmission suggest high basic reproduction 10 Jul 2020 number R0, variation in the number of secondary transmissions (often characterised by so-called superspreading events) may be large as some countries have observed fewer local transmissions than others. version 2 Methods: We quantified individual-level variation in COVID-19 (revision) report report transmission by applying a mathematical model to observed outbreak sizes 03 Jul 2020 in affected countries. We extracted the number of imported and local cases in the affected countries from the World Health Organization situation report and applied a branching process model where the number of secondary version 1 transmissions was assumed to follow a negative-binomial distribution. -

By Sean B. Carroll

Educator Supplements to the book, THE SERENGETI RULES THE QUEST TO DISCOVER HOW LIFE WORKS AND WHY IT MATTERS BY SEAN B. CARROLL Prepared by Paul Strode Teacher of Biology at Fairview High School Boulder, Colorado 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. SUMMARY OF THE SERENGETI RULES 4–8 II. INTRODUCTION TO QUESTION SETS FOR THE SERENGETI RULES 9–11 III. ENGAGEMENT QUESTIONS 12–21 IV. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 22–30 V. ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS 31–40 VI. COURSE CURRICULUM ALIGNMENTS: AP BIOLOGY, IB BIOLOGY, NGSS 41–53 VII. EXAMPLE ADVANCED BIOLOGY CURRICULUM MAP FOR THE SERENGETI RULES 54–57 2 HOW TEACHERS MIGHT USE THE SERENGETI RULES IN THE CLASSROOM The Serengeti Rules, molecular biologist Sean Carroll takes the reader on a journey through the history of the scientific discovery of many of nature’s most important regulatory mechanisms, from molecules to megafauna. In the spirit of Theodisius Dobzhansky, Carroll teaches us in The Serengeti Rules that nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of regulation. Thus, at the very center of the book is the big, biological idea of homeostasis. Indeed, a key to understand- ing how living systems work and the supporting roles played by evolutionary processes is understanding how a rela- tively stable environment, be it in a cell or in an ecosystem, is maintained and regulated. Throughout the book, Carroll tells the stories of the scientists—and their discoveries—that have given us our current understanding of regulation in nature. But in the stories, Carroll also teaches the reader about the nature of science and scientific reasoning, the impor- tance of modeling, and how scientific discovery is full of determination and success but also frequented with failure. -

Shepherd School Symphony Orchestra

SHEPHERD SCHOOL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA LARRY J. LIVINGSTON, conductor JULIE LANDSMAN, faculty soloist LAURA HUNTER, faculty soloist Monday, January 30, 1984 8 :00 p. m. in Hamman Hall, Houston Syzygy Concert (Penderecki) Tuesday, January 31, 1984 8:00 p.m. in Hamman Hall, Houston Wednesday, February 1, 1984 4:30 p.m. in Caruth Auditorium, Southern Methodist University, Dallas Thursday, February 2, 1984 1:30 p.m. in the Tarrant County Convention Center Theatre, Fort Worth, TMEA conference the RICE UNIVERSITY ~~rd ofMusic PROGRAM Die Meistersinger: Prelude Richard Wagner (1813-1883) \Orn,"'~~ to~~ Threnody: To the Victims of Hiroshima (1961) / Krzysztof Penderecki ~ (b.1933) © ~·.2~J - 8~as3" / Concerto No. 1 for Horn in Eb major, Op. 11 Allegro Andante *Allegro Tcii~\...."'1twte.--~ ~IC). · r'I.V'-tt.,~·I 1~) 2°~- . Julie Landsman, horn yYI - Pictures at an Exhibition (arr. Ravel)@<CI , \Q t° q ~,y Modest Mussorgsky t Promenade 4 ~ I • - I - r-,;.;:, (1839-1881) tI Gnomus Promenade tII II vecchio castello (The Old Castle) 70T,.4;(;:' .tME':-;,; Promenade tIII Tuileries IV Bydlo Promenade V Ballet des poussins dans leurs coques (Ballet of the Chickens in their Shells) VI Samuel Goldenberg und Schmuyle tVII Limoges-Le Marche \VIII Catacombae: Sepulcrum Romanum Con Mortuis in lingua mortua (Speaking to the Dead in a Dead Language) i.. f tIX La Cabane sur des pattes de poule (The Hut on Fowls' Legs) ,Sf~ (-6 tX La grande porte de Kiev (The Great Gate of Kiev) 7 /q Laura Hunter, saxaphone I ilf!.o ~~ 1 ~ - • ~ o- ~ ~ J -.f) *Tl movement only to be performed at The Tarrant County Convention Center Theatre in Fort Worth for the TMEA Conference. -

Sphecos: a Forum for Aculeate Wasp Researchers

SPHECOS Number 4 - January 1981 A Newsletter for Aculeate Wasp Researchers Arnold S. Menke, editor Systematic Entomology Laboratory, USDA c/o u. S. National Museum of Natural History washington DC 20560 Notes from the Editor This issue of Sphecos consists mainly of autobiographies and recent literature. A highlight of the latter is a special section on literature of the vespid subfamily Vespinae compiled and submitted by Robin Edwards (seep. 41). A few errors in issue 3 have been brought to my attention. Dr. Mickel was declared to be a "multillid" expert on page l. More seriously, a few typographical errors crept into Steyskal's errata paper on pages 43-46. The correct spellings are listed below: On page 43: p. 41 - Aneusmenus --- p. 108 - Zaschizon:t:x montana and z. Eluricincta On page 45: p. 940 - ----feminine because Greek mastix --- p. 1335 - AmEl:t:oEone --- On page 46: p. 1957 - Lasioglossum citerior My apologies to Dr. Mickel and George Steyskal. I want to thank Helen Proctor for doing such a fine job of typing the copy for Sphecos 3 and 4. Research News Ra:t:mond Wah is, Zoologie generale et Faunistique, Faculte des Sciences agronomiques, 5800 GEMBLOUX, Belgium; home address: 30 rue des Sept Collines 4930 CHAUDFONTAINE, Belgium (POMPILIDAE of the World), is working on a revision of the South American genus Priochilus and is also preparing an annotated key of the members of the Tribe Auplopodini in Australia (AuElOEUS, Pseudagenia, Fabriogenia, Phanagenia, etc.). He spent two weeks in London (British Museum) this summer studying type specimens and found that Turner misinterpreted all the old species and that his key (1910: 310) has no practical value. -

ABSTRACT BOOK – 17Th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

{ ABSTRACT BOOK { 17th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Kurume, Fukuoka, Japan June 28, 2017 Preface The International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors (LTD) is the biennial meeting to present and discuss latest results on research and development of cryogenic detectors for radiation and particles, and on applications of those detectors. The 17-th workshop will be held at Kurume City Plaza in Kurume city, Fukuoka Japan from 17th of July through 21st. The workshop will be organized with the following six sessions: 1. Keynote talks 2. Sensor Physics & Developments, • TES, MMC, MKIDS, STJ, Semiconductors, Novel detectors, others 3. Readout Techniques & Signal processing • Electronics, Multiplexing, Filtering, Imaging, Microwave circuit, Data analysis, others 4. Fabrication & Implementation Techniques • Fabrication process, MEMS, Pixel array, Microwave wirings, others 5. Cryogenics and Components • Refrigerators, Window techniques, Optical Blocking Filters, others 6. Applications • Electromagnetic wave & photon (mm-wave, THZ, IR, Visible, X-ray, Gamma-ray), Particles, Neutrons, CMB, Dark Matter, Neutrinos, Particle & Nuclear Physics, Rare Event Search, Material Analysis & Life Science Kurume is a fabulous location for the workshop. It is known by good local foods and good Sake (Japanese rice wine), and also for traditional fabric called Kurume Gasuri. The LTD17 workshop provides you a wonderful opportunity to exchange your ideas and extend your experience on the low temperature detectors. We hope you will join and enjoy. LOC of 17th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors ii Contents Oral presentations 1 Keynote talks 2 O-1 Low Temperature Detectors (for Dark matter and Neutrinos) 30 Years ago. The Start of a new experimental Technology. (Franz von Feilitzsch) ............................. -

Michael R. Thornton

1 MICHAEL R. THORNTON Associate Professor of Horn, University of Colorado Boulder 301 UCB 3309 West 109th Court (303) 492-7721 Westminster, CO 80031 [email protected] (303) 503-5238 Education: The Juilliard School 1996 {Partial Fulfillment of Master of Music Requirements. Terminated degree for appointment as Principal Horn of the Honolulu Symphony} Manhattan School of Music 1995-1996 {Partial Fulfillment of Master of Music in Orchestral Performance Requirements} Temple University 1994-1995 {Partial Fulfillment of Master of Music Requirements} -Graduate Teaching Assistantship in Music History Temple University, Bachelor of Music in Horn Performance 1991-1994 -Magna cum Laude -Completed in three years Teaching Experience: The University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, Colorado Associate Professor of Horn 2012 Assistant Professor of Horn 2007 Instructor of Horn 1999 -Applied instruction of horn majors at the undergraduate and graduate levels -Lecturing and conducting weekly horn studio class -Instruction of Brass Repertoire and Pedagogy courses -Brass Chamber Music coaching -Faculty Brass Quintet -Director of the University of Colorado Horn Choir -Faculty Recital performances -Advising and student committee work at undergraduate and graduate levels -Recruiting activities and web presence Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 2005-2006 Horn Professor -Applied instruction of horn majors at the undergraduate and graduate levels -Lecturing and conducting weekly horn studio class -Faculty Brass Quintet Colorado College -

March 20, 2012, Vol. 58 No. 26

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday March 20, 2012 Volume 58 Number 26 www.upenn.edu/almanac Penn’s Graduate School Rankings Penn’s 2012 Commencement Speaker and . Each year US News & World Report ranks Honorary Degree Recipients professional school programs in business, education, engineering, law and medicine. This Geoffrey Canada year’s rankings of the best graduate schools include will be the three of Penn’s schools which retained the positions Commencement they had last year: Penn’s Perelman School of Speaker at Medicine ranked #2 (tied with Johns Hopkins), the Penn’s 256th Wharton School ranked #3 and Penn Law ranked Commencement #7. Penn’s Graduate School of Education moved on Monday, May up three ranks since last year and is now ranked #9. 14, 2012. He US News & World Report periodically ranks other and these other fields, such as public affairs (Fels). individuals will The 2013 edition of their Best Graduate be presented Schools book will be available on April 3. The with honorary full rankings are available on the US News & degrees from the World Report website at www.usnews.com University of 2012 2013 Pennsylvania. Geoffrey Canada Ruzena Bajcsy Akira Endo Perelman School of Medicine 2 2 Pediatrics 1 2 Women’s Health 6 4 Internal Medicine 5 5 Drug/Alcohol Abuse Treatment 6 5 Clinical Psychology 6 AIDS — 9 Primary Care 9 11 Wharton School 3 3 Executive MBA 1 1 Finance 1 1 Marketing 2 2 International 3 2 Production/Operations 3 2 Accounting 2 3 Management 4 3 Entrepreneurship 5 5 Supply Chain/Logistics 3 6 Peter Lax John Lewis David Petraeus Anna Smith Information Systems 6 7 Law School 7 7 Vice President and Secretary of the University Leslie Laird Kruhly has announced the 2012 Graduate School of Education 12 9 honorary degree recipients and the Commencement Speaker. -

Commencement Program 2012, University of Pennsylvania

256 th COMMENCEMENT 256th COMMENCEMENT MAY 14 2012 MAY 14 MAY 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA KEEPING FRANKLIN’S PROMISE In the words of one elegiac tribute, “Great men have two lives: one which occurs while they work on this earth; a second which begins at the day of their death and continues as long as their ideas and conceptions remain powerful.” These words befit the great Benjamin Franklin, whose inventions, innovations, ideas, writings, and public works continue to shape our thinking and renew the Republic he helped to create and the institutions he founded, including the University of Pennsylvania. Nowhere does Franklin feel more contemporary, more revolutionary, and more alive than at the University of Pennsylvania. His startling vision of a secular, nonsectarian Academy that would foster an “Inclination join’d with an Ability to serve Mankind, one’s Country, Friends and Family” has never ceased to challenge Penn to redefine the scope and mission of the modern American university. When pursued vigorously and simultaneously, the two missions – developing the inclination to do good and the ability to do well – merge to help form a more perfect university that educates more capable citizens for our democracy. Penn has embodied and advanced Franklin’s revolutionary vision for 272 years. Throughout its history, Penn has extended the frontiers of higher learning and research to produce graduates and scholars whose work has enriched the nation and all of humanity. The modern liberal arts curriculum as we know it can trace its roots to Franklin’s innovation to have Penn students study international commerce and foreign languages. -

Towards a New Enlightenment?

Towards a New Enlightenment? A Transcendent Decade Preface This book, Towards a New Enlightenment? A Transcendent Decade, is the eleventh in an annual series that BBVA’s OpenMind project dedicates to disseminating greater knowledge on the key questions of our time. We began this series in 2008, with the first book, Frontiers of Knowledge, that celebrated the launching of the prizes of the same name awarded annually by the BBVA Foundation. Since then, these awards have achieved worldwide renown. In that first book, over twenty major scientists and experts used language accessible to the general public to rigorously review the most relevant recent advances and perspectives in the different scientific and artistic fields recognized by those prizes. Since then, we have published a new book each year, always following the same model: collections of articles by key figures in their respective fields that address different aspects or perspectives on the fundamental questions that affect our lives and determine our futu- re: from globalization to the impact of exponential technologies, and on to include today’s major ethical problems, the evolution of business in the digital era, and the future of Europe. The excellent reaction to the first books in this series led us, in 2011, to create OpenMind (www.bbvaopenmind.com), an online community for debate and the dissemination of knowle- dge. Since then, OpenMind has thrived, and today it addresses a broad spectrum of scientific, technological, social, and humanistic subjects in different formats, including our books, as well as articles, posts, reportage, infographics, videos, and podcasts, with a growing focus on audiovisual materials. -

Controlling Methane at ERD and ISCR Applications

REMEDIATION Controlling Methane at ERD and ISCR Applications Active measures to control the production of methane can offer multiple advantages in terms of cost, treatment effi ciency and safety. >> JIM MUELLER, PH.D., ANTONIS KARACHALIOS, PH.D., AND TROY FOWLER n-situ chemical reduction (ISCR) and enhanced Many readers will know from their own experiences that reductive dehalogenation (ERD) have demonstrated these amendments have been widely used with varying success in the remediation of numerous recalcitrant degrees of success in terms of overall remedial perfor- and toxic compounds, including chlorinated ethenes mance. One seemingly universal phenomenon has been and hexavalent chromium. ISCR describes the the biological production of methane, especially during Icombined effect of stimulated biological oxygen consump- the early phases of remedial actions (look for it and you tion (via fermentation of an organic carbon source), direct will find it). Active measures to control the production of chemical reduction with zero-valent iron (ZVI) or other methane can offer multiple advantages in terms of cost, reduced metals. As described by Brown et al (2009)[1], the treatment efficiency and safety. corresponding enhanced thermodynamic decomposition reactions that are realized at the lowered redox (Eh) condi- What Is a Methanogen? tions allow for more effective mineralization of many con- In the 1970s, Dr. Carl Woese and his colleagues at the Uni- stituents of interest (COIs). A growing number of ERD versity of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign studied prokary- substrates and other accelerated anaerobic bioremediation otic relationships using DNA sequences, and they found technologies (e.g., emulsified oils, non-emulsified oils, car- that microbes that produce methane[2] – or methanogens bon-based hydrogen release compounds, vegetable matter – are Archaea. -

Rick Rowley, Pianist 2001 Parker Ln, #135 Austin, TX 78741 Cell: (512) 497-7020 Home: (512) 443-6726 [email protected]

Rick Rowley, Pianist 2001 Parker Ln, #135 Austin, TX 78741 Cell: (512) 497-7020 Home: (512) 443-6726 [email protected] EDUCATION Washburn University (Undergraduate Studies) (1972-3) Classes with Leon Fleisher and Lili Kraus – Round Top Festival (1974-1977) Classes with Gwendolyn Koldofksy in art song – Round Top Festival (1974) INSTRUCTION James Rivers (Washburn University), Private Piano Study and Washburn University (1971, 1972, 1973) Jeannette Haien (Mannes College, NY), Private Piano Study (1974-1978) Carl Schachter (Mannes and Queens Colleges, NY), Private Piano Study and Schenkerian Analysis (1978-1980) Patricia Zander (New England Conservatory of Music), Private Piano Study (1975-1979) ACADEMIC POSITIONS University of Texas at Austin: Butler School of Music, Lecturer in Vocal Accompanying (1995-1997) University of Texas at Austin: Butler School of Music, Lecturer in Vocal Accompanying (1998-1999) University of Texas at Austin: Musical Theater Class for Actors and Singers (1999) University of Texas at Austin: Butler School of Music, Lecturer in Vocal Accompanying (2003 – Present) PERFORMANCES International Guest Artist recital with Brian Lewis, Violin, San Salvador, El Salvador, 5th Annual Festival Suzuki Internacional de Musica El Salvador, 2010 (by invitation) French-American Vocal Academy, Art Songs of Aboulker and Poulenc, Perigueux, France, 2010 (by invitation) National Guest Artist recital with James Markey, Bass Trombone, Austin, TX, International Trombone Festival, 2010 (by invitation) Collaborative Pianist, International