How Can Decentralized Systems Solve System-Level Problems? An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Energy Star Qualified Buildings

1 ENERGY STAR® Qualified Buildings As of 1-1-03 Building Address City State Alabama 10044 3535 Colonnade Parkway Birmingham AL Bellsouth City Center 600 N 19th St. Birmingham AL Arkansas 598 John L. McClellan Memorial Veterans Hospital 4300 West 7th Street Little Rock AR Arizona 24th at Camelback 2375 E Camelback Phoenix AZ Phoenix Federal Courthouse -AZ0052ZZ 230 N. First Ave. Phoenix AZ 649 N. Arizona VA Health Care System - Prescott 500 Highway 89 North Prescott AZ America West Airlines Corporate Headquarters 111 W. Rio Salado Pkwy. Tempe AZ Tempe, AZ - Branch 83 2032 West Fourth Street Tempe AZ 678 Southern Arizona VA Health Care System-Tucson 3601 South 6th Avenue Tucson AZ Federal Building 300 West Congress Tucson AZ Holualoa Centre East 7810-7840 East Broadway Tucson AZ Holualoa Corporate Center 7750 East Broadway Tucson AZ Thomas O' Price Service Center Building #1 4004 S. Park Ave. Tucson AZ California Agoura Westlake 31355 31355 Oak Crest Drive Agoura CA Agoura Westlake 31365 31365 Oak Crest Drive Agoura CA Agoura Westlake 4373 4373 Park Terrace Dr Agoura CA Stadium Centre 2099 S. State College Anaheim CA Team Disney Anaheim 700 West Ball Road Anaheim CA Anahiem City Centre 222 S Harbor Blvd. Anahiem CA 91 Freeway Business Center 17100 Poineer Blvd. Artesia CA California Twin Towers 4900 California Ave. Bakersfield CA Parkway Center 4200 Truxton Bakersfield CA Building 69 1 Cyclotron Rd. Berkeley CA 120 Spalding 120 Spalding Dr. Beverly Hills CA 8383 Wilshire 8383 Wilshire Blvd. Beverly Hills CA 9100 9100 Wilshire Blvd. Beverly Hills CA 9665 Wilshire 9665 Wilshire Blvd. -

The State of Public Education in New Orleans

The State of Public Education in New Orleans 20 18 Kate Babineau Dave Hand Vincent Rossmeier The mission of the Cowen Institute Amanda Hill is to advance Executive Director, Cowen Institute public education At the Cowen Institute, we envision a city where all children have access to a world-class education and where all youth are on inspiring pathways to college and careers. We opened our doors in 2007 to chronicle and analyze the transformation of the K-12 education system in New Orleans. and youth success Through our annual State of Public Education in New Orleans (SPENO) report, public perception polls, and issue briefs, we aim to share our analysis in relevant and accessible ways. in New Orleans We are at a pivotal moment in New Orleans’ history as schools return to the Orleans Parish School Board’s oversight. This report distills the complexities of governance, enrollment, accountability, school performance, student and educator demographics, and transportation. Additionally, this and beyond. report looks ahead at what is on the horizon for our city’s schools. We hope you find this information useful. As we look forward, we are more committed than ever to ensuring that all students have access to high-quality public education and meaningful post-secondary opportunities. We wish to To further that mission, the Cowen Institute focuses on K-12 education, college and career acknowledge the incredible work and determination of educators, school leaders, parents, non- success, and reconnecting opportunity youth to school and work. profit partners, civic leaders, and, most of all, young people in our city. -

Propeller Club of the U.S. Port of New Orleans Membership Roster - 2015

Propeller Club of the U.S. Port of New Orleans Membership Roster - 2015 FIRST LAST COMPANY ADDRESS E-MAIL OFFICE PHONE Charlie Andrews, Jr. 11117 Winchester Park Drive New Orleans, LA 70128 504-227-7009 William S. App, Jr. J.W. Allen & Co., Inc. 200 Crofton Rd., Box 34 Kenner, LA 70065 [email protected] 504-464-0181.111 William Ayers 822 N. Austin St. Seguin, TX 78155 830-372-2244 Jimmy Baldwin Coastal Cargo, Inc. 1555 Poydras St., Suite 1600 New Orleans, LA 70112 [email protected] 504-587-1125 William J. Baraldi Buck Kreihs Marine Repair, LLC PO Box 53305 New Orleans, LA 70153 [email protected] 504-524-7681 Robert R. Barkerding, Jr. Admiral Security Services, Inc. 1010 Common St., Suite 2970 New Orleans, LA 70112 [email protected] 504-831-1408 Frank J. Basile Entech Associates PO Box 1470 Houma, LA 70361-1470 [email protected] 985-868-5524 Perry Beebe Perry Beebe & Associates, LLC 141 Hwy. 22 E, Unit 4A Madisonville, LA 70447 [email protected] 504-400-1713 Don Belovin Bay Diesel Corp. 3742 Cook Blvd. Chesapeake, VA 23323 [email protected] 757-485-0075 Julie Biggers All Scrap Metals 7 Veterans Blvd. Kenner,LA 70062 [email protected] 504-471-0241 Richard E. Boyer Pacific-Gulf Marine, Inc. 401 Whitney Ave., Ste. 511 Gretna, LA 70056 [email protected] 504-362-8121 Ron Branch Louisiana Maritime Assoc. 3939 N. Causeway Blvd., Suite 102 Metairie, LA 70002 [email protected] 504-833-4190 Conrad Breit C. Breit Marine Services, LLC 111 Acadia Ln Destrehan, LA 70047 [email protected] 504-913-7960 Hjalmar E. -

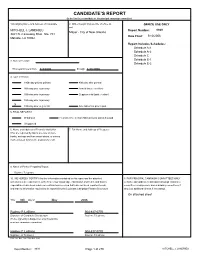

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU Report Number: 9939 Mayor - City of New Orleans 3421 N. Casueway Blvd. Ste. 701 Date Filed: 5/10/2006 Metairie, LA 70002 Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule C 3. Date of Election Schedule E-1 Schedule E-2 This report covers from 4/3/2006 through 4/30/2006 4. Type of Report: 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary X 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more banks, savings and loan associations, or money market mutual fund as the depository of all 9. Name of Person Preparing Report Daytime Telephone 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. Name and address of principal campaign committee, expenditures have been made nor contributions received that have not been reported herein, committee’s chairperson, and subsidiary committees, if and that no information required to be reported by the Louisiana Campaign Finance Disclosure any (use additional sheets if necessary). -

2019 Satchmo Summerfest – Final Fest Details Revealed

French Quarter Festivals, Inc. Emily Madero, President & CEO 400 North Peters, Suite 205 New Orleans, LA 70130 www.fqfi.org Contact: Rebecca Sell, Marketing Director Office: 504-522-5730/Cell: 504-343-5559 Email: [email protected] _____________________________________________________________________________________ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 19th Anniversary Satchmo SummerFest presented by Chevron THREE FULL DAYS of FEST NEW ORLEANS, LA (July 25, 2019) – The 19th Anniversary Satchmo SummerFest presented by Chevron is August 2-4, 2019 at the New Orleans Jazz Museum at the Mint. Produced by French Quarter Festivals, Inc. (FQFI), Satchmo SummerFest is an unparalleled celebration of the life, legacy, and music of New Orleans' native son, Louis Armstrong. Recently named one of the most “interesting things to experience in Louisiana” by Oprah Magazine, the event brings performances from New Orleans’ most talented musicians, with a focus on traditional and contemporary jazz and brass bands. The nominal daily admission of $6 (children 12 and under are free) helps support local musicians and pay for the event. Admission also provides access to the Jazz Museum’s collection and exhibitions plus indoor activities like Pops’ Playhouse for Kids powered by Entergy and the Hilton Satchmo Legacy Stage featuring presentations by renowned Armstrong scholars. Ayo Scott Selected as 2019 Poster Artist New Orleans artist Ayo Scott was selected as the 2019 French Quarter Festivals, Inc. artist, creating the artwork for both the French Quarter Festival and Satchmo SummerFest posters. Scott graduated from Xavier University in 2003 and attended graduate school at The Institute of Design in Chicago. Immediately after Hurricane Katrina, he returned home to help the city rebuild. -

General Parking

NINE MINUTES FROM PARKING POLICIES FOR GENERAL PARKING MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME There is no general parking for vehicles, • 1000 Poydras Street MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME RVs, buses and limousines for the • 522 S Rampart Street PASS HOLDERS National Championship Game. All lots The failure of any guests to obey the surrounding the Mercedes-Benz 10 MINUTES FROM instructions, directions or requests of Superdome will be pass lots only. MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME event personnel, stadium signage or Information regarding additional • 1000 Perdido Street management’s rules and regulations parking near the Mercedes-Benz Additional Parking lots can be found may cause ejection from the event Superdome can be found below. at parking.com. parking lots at management’s discretion, and/or forfeiture and cancellation of the parking PREMIUM PARKING LOTS RV RESORTS pass, without compensation. FIVE MINUTES FROM FRENCH QUARTER RV RESORT MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME 10 MINUTES FROM TAILGATING • 1709 Poydras Street MERCEDES- BENZ SUPERDOME Tailgating in Mercedes- Benz 500 N. Claiborne Avenue Superdome lots is prohibited for the NINE MINUTES FROM New Orleans, LA 70112 National Championship Game. MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME Phone: 504.586.3000 • 400 Loyola Avenue Fax: 504.596.0555 TOWING SERVICE Email: [email protected] For towing services and assistance, 10 MINUTES FROM Website: fqrv.com please call 504-522-8123. Please raise MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME your car hood and/or notify an officer • 2123 Poydras Street THREE OAKS AND A PINE RV PARK at any lot entrance. • 400 S Rampart Street 15–20 MINUTES FROM • 415 O’Keefe Avenue MERCEDES- BENZ SUPERDOME DROP-OFF AND 7500 Chef Menteur Highway • 334 O’Keefe Avenue PICK UP AREAS New Orleans, LA 70126 Guests can utilize the drop off and pick Additional parking lots can be found Phone: 504.779.5757 up area at the taxi drop off zone on at premiumparking.com. -

The Port of New Orleans: an Economic History, 1821-1860. (Volumes I and Ii)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1985 The orP t of New Orleans: an Economic History, 1821-1860. (Volumes I and II) (Trade, Commerce, Slaves, Louisiana). Thomas E. Redard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Redard, Thomas E., "The orP t of New Orleans: an Economic History, 1821-1860. (Volumes I and II) (Trade, Commerce, Slaves, Louisiana)." (1985). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4151. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4151 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction Is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages In any manuscript may have Indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques Is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When It Is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to Indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to Indicate this. -

Exploring Gender in Pre- and Post-Katrina New Orleans

Re-visioning Katrina: Exploring Gender in pre- and post-Katrina New Orleans Chelsea Atkins Skelley Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In English Steven G. Salaita, chair Gena E. Chandler Katrina M. Powell April 26, 2011 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: gender, New Orleans, Hurricane Katrina, Jezebel, gothic, black female body Re-visioning Katrina: Exploring Gender in pre- and post-Katrina New Orleans Chelsea Atkins Skelley ABSTRACT I argue that to understand the gender dynamics of New Orleans, Hurricane Katrina, and the storm’s aftermath, one must interrogate the cultural conflation of the black female body and the city’s legacy to explore what it means and how it situates real black women in social, cultural, and physical landscapes. Using a hybrid theoretical framework informed by Black feminist theory, ecocriticism, critical race feminism, and post- positivist realism, I explore the connections between New Orleans’ cultural and historical discourses that gender the city as feminine, more specifically as a black woman or Jezebel, with narratives of real black females to illustrate the impact that dominant discourses have on people’s lives. I ground this work in Black feminism, specifically Hortense Spillers’s and Patricia Hill Collins’s works that center the black female body to garner a fuller understanding of social systems, Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality, and Evelyn Hammonds’s call for a reclamation of the body to interrogate the ideologies that inscribe black women. In addition, I argue that black women should reclaim New Orleans’ metaphorical black body and interrogate this history to move forward in rebuilding the city. -

Than 200 Performances on 19 Stages Tank & the Bangas, Irma Thomas, Soul Rebels, Kermit Ruffins Plus More Than 20 Debuts Including Rickie Lee Jones

French Quarter Festivals, Inc. 400 North Peters, Suite 205 New Orleans, LA 70130 Contact: Rebecca Sell phone: 504-522-5730 cell: 504-343-5559 email: [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE French Quarter Festival presented by Chevron Returns as a Live Event September 30 – October 2, 2021! Special fall festival edition brings music, community, and celebration back to the streets! New Orleans (June 15, 2021)— The non-profit French Quarter Festivals, Inc. (FQFI) is excited to announce the return of French Quarter Festival presented by Chevron. Festival organizers didn’t want to let another calendar year pass without bringing back this celebrated tradition and critical economic driver back for fans, musicians, and local businesses. The one-time-only fall edition of French Quarter Festival takes place September 30 – October 2 across venues and stages in the French Quarter neighborhood. Attendees will experience the world’s largest celebration of Louisiana’s food, music, and culture during the free three-day event. As New Orleans makes its comeback, fall 2021 will deliver nearly a year’s-worth of events in a few short months. At the City's request, FQFI organizers have consolidated festival activities into an action-packed three-days in order allow the city to focus its security and safety resources on the New Orleans Saints home game on Sunday, October 3. FQFI has shifted programming in order to maximize the concentrated schedule and present time-honored festival traditions, stages, and performances. The event will bring regional cuisine from more than 50 local restaurants, hundreds of Louisiana musicians on 19 stages, and special events that celebrate New Orleans’ diverse, unique culture. -

New Orleans C L a S S - a Office Space Opportunities

DOWNTOWN New Orleans C l a s s - A Office Space Opportunities June 10, 2020 1 Class-A Office Space :: Downtown New Orleans Index of Opportunities Property Name Page No. Hancock Whitney Center (One Shell Square) 5. Place St Charles 12. Energy Centre 19. Pan American Life Center 30. One Canal Place 36. Regions Center | 400 Poydras 51. First Bank and Trust Tower 59. Benson Tower 68. 1515 Poydras Building 70. Entergy Corp. Building 79. DXC.technology Building 82. 1555 Poydras Building 89. Poydras Center 96. 1250 Poydras Plaza 105. 1010 Common Building 109. Orleans Tower | 1340 Poydras 111. 2 Downtown New Orleans Office Market Overview: Downtown New Orleans offers an affordable Class-A office market totaling 8.9 million square feet. Significant new office leases include the following: Hancock-Whitney Bank, seven floors at Hancock Whitney Center (One Shell Square) Accruent, a technology firm, leased an entire floor, 22,594 square feet, at 400 Poydras DXC.Technology announced a long term lease at 1615 Poydras, leasing two floors IMTT announced a long term lease at 400 Poydras 2020 Class A office occupancy: 87% occupied 14 total Class-A properties Average building size, 637,737 square feet $19.75 average rent per square foot) 8,928,318 total leasable Class A office space in market Class A office towers in New Orleans, ranked by total leasable square feet: Hancock Whitney Center 92% leased 1,256,991 SF Place St Charles 91% leased 1,004,484 SF Energy Centre 85% leased 761,500 SF Pan-American Life Center 83% leased 671,833 SF One Canal Place 82% leased 630,581 SF Regions Center/400 Poydras 86% leased 608,608 SF First Bank & Trust Tower 89% leased 545,157 SF Benson Tower 99% leased 540,208 SF 1515 Poydras Building 59% leased 529,474 SF Entergy Corp. -

Download Download

William Frantz Public School: One School, One Century, Many Stories Connie Lynn Schaffer University of Nebraska at Omaha [email protected] Corine Meredith Brown Rowan University [email protected] Meg White Stockton University [email protected] Martha Graham Viator Rowan University [email protected] Abstract William Frantz Public School (WFPS) in New Orleans, Louisiana, played a significant role in the story of desegregation in public K-12 education in the United States. This story began in 1960 when first-grader, Ruby Bridges, surrounded by federal marshals, climbed the steps to enroll as the school’s first Black student. Yet many subsequent stories unfolded within WFPS and offer an opportunity to force an often-resisted discussion regarding systemic questions facing present-day United States public education—racial integration, accountability, and increasing support for charter schools. In this article, the story is told first in the context of WFPS and then is connected to parallels found in schools in New Orleans as well as other urban areas in the United States. Introduction Stories from American history are taught in thousands of public schools every year, but at times a school is a history lesson and a story in itself. Such is the case of William Frantz Public School (WFPS), an elementary school in the Upper Ninth Ward of New Orleans. The nearly century- long story of WFPS includes a very distinct chapter captured in American history textbooks, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. However, WFPS epitomizes many contemporary lesser- known stories within public schools in the United States, stories which deeply challenge the vision of Horace Mann, the noted patriarch of American public education. -

How New Orleans Criminalizes Women, Girls, Youth and LGBTQ & Latinx People 2 PREPARED BY

How New Orleans Criminalizes Women, Girls, Youth and LGBTQ & Latinx People 2 PREPARED BY TAKEMA ROBINSON ANNETTE HOLLOWELL AUDREY STEWART CARYN BLAIR CHALLENGING CRIMINALIZATION: HOW NEW ORLEANS CRIMINALIZES WOMEN, GIRLS, YOUTH AND LGBTQ & LATINX PEOPLE New Orleans has been labeled “ground zero” for criminal justice reform in America in a nod to the city’s history of overreliance on incarceration as well as recent successes in the long battle for criminal justice reform. Following decades of organizing and advocacy, reform of the city’s police and jails has taken root in the form of federal monitoring and oversight of the jail and police department and in drastic reduction of the daily jail population from 6,000 in 2005 to less than 1,800 in July 2015.1 Responding to the concerted efforts of grassroots organizations—including Voice of The Experienced (VOTE),* Youth BreakOUT!, Women With A Vision (WWAV), Orleans Parish Prison Reform Coalition (OPPRC) and national allies like the Vera Institute and the MacArthur Foundation—Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s administration has made criminal justice reform a central priority over the past six years. However, despite these considerable strides, New Orleans remains a national and world leader in systemic criminalization and incarceration of its citizens. New Orleans is Louisiana’s largest city and This study centers the voices and experiences also the city with the largest incarceration of youth, women, girls, Latinxs and LGBTQ rate. In a state that incarcerates more citizens people who face particular injustices due per capita than anywhere else in the world, to intersecting and interlocking systems New Orleans ranks at the top of the list, of white supremacy and patriarchy as they with approximately 90 percent of those are shuttled into and through New Orleans’ incarcerated being Black.2 And although criminal justice system.