Intellectual Property, Part II: Trade Marks and Unfair Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology

KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KUMASI INSTITUTE OF DISTANCE LEARNING OPTIMAL PRODUCTION SCHEDULING, CASE STUDY: GUINESS GHANA BREWERY LIMITED, KUMASI BY DANKWAH JOSEPH A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE INSTITUTE OF DISTANCE LEARNING, DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN INDUSTRIAL MATHEMATICS. JUNE, 2011. DECLARATION I hereby declare that this project work was fully undertaken by me under supervision and has not in part or whole been presented for another project. DANKWAH JOSEPH …………...... DATE ……………………… (Student) MR. F.K. DARKWA ………………… DATE …………………………… (Head of Department) PROF. I.K.DONTWI ……………………... DATE ……………………………….. (Dean of IDL) MR. F. K. DARKWA ………………….. DATE ………………………….. (Supervisor) ii ABSTRACT As Production systems expand, there is a tendency for the scheduling activities to become complex, or at least more demanding with respect to the time required for their performance Previous production scheduling involves complicated iterative procedures. A new approach brings out the basic principle involved and leads to a simple solution. Production of a given commodity is to be scheduled for a regular and capacity to meet known future requirements while minimizing total production and inventory costs. For the objective function, I intend to find the optimum production schedule by minimizing the total production and inventory cost calculated through the production schedules of orders. The Northwest Corner Rule, the Least Cost Method, and the Vogel‘s Approximation Method (VAM) were used to obtain an initial basic feasible solution (bfs). Improving solution to optimality was carried out using The Modified Distribution Method (MODI). The production was modelled as a balanced transportation problem and solved using an excel solver to obtain the optimal production schedule and the results reported. -

View Annual Report

Diageo Annual Report 2008 ANNUAL REPORT 2008 Diageo plc 8 Henrietta Place London W1G 0NB United Kingdom Tel +44 (0) 20 7927 5200 Fax +44 (0) 20 7927 4600 www.diageo.com Registered in England No. 23307 © 2008 Diageo plc. All rights reserved. All brands mentioned in this Annual Report are trademarks and are registered and/or CELEBRATING LIFE, otherwise protected in accordance with applicable law. EVERY DAY, EVERYWHERE CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT P4 CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S REVIEW P6 OUTSTANDING BRANDS P8 OUR MARKETS P10 PERFORMANCE SUMMARY 68 Market risk sensitivity analysis 148 Accounting policies of the company 2 Highlights 69 Critical accounting policies 149 Notes to the company financial statements 4 Chairman’s statement 71 Adoption of IFRS 151 Principal group companies 6 Chief executive’s review 71 New accounting standards 8 Outstanding brands ADDITIONAL INFORMATION FOR 10 Our markets GOVERNANCE SHAREHOLDERS 12 Historical information 73 Our board of directors and the 153 Legal proceedings executive committee 153 Related party transactions BUSINESS DESCRIPTION 74 Directors and senior management 153 Material contracts 17 Strategy 76 Directors’ remuneration report 153 Debt securities 18 Premium drinks 88 Corporate governance report 153 Share capital 24 Disposed businesses 94 Directors’ report 155 Memorandum and articles of association 24 Risk factors 158 Exchange controls 27 Cautionary statement concerning FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 158 Documents on display forward-looking statements 97 Independent auditor’s report to the 158 Taxation members of -

Branding Agricultural Commodities: the Development Case for Adding Value Through Branding

Project: Series: Author: New Business Models for Topic Brief Series Chris Docherty Sustainable Trading Relationships Branding Agricultural Commodities: The development case for adding value through branding i This paper is part of a publication series generated by the New Business Models for Sustainable Trading Relationships project. The partners in the four-year project – the Sustainable Food Laboratory, Rainforest Alliance, the International Institute for Environment and Development, the International Center for Tropical Agriculture, and Catholic Relief Services – are working together to develop, pilot, and learn from new business models of trading relationships between small-scale producers and formal markets. By working in partnership with business and looking across a diversity of crop types and market requirements – fresh horticulture, processed vegetables, pulses, certified coffee and cocoa – the collaboration aims to synthesize learning about how to increase access, benefits, and stability for small-scale producers while generating consistent and reliable supplies for buyers. For further information see: www.sustainablefoodlab.org/projects/ ag-and-development and www.linkingworlds.org/ Please contact Abbi Buxton at [email protected] if you have any questions or comments. ISBN 978-1-84369-846-3 Available to download at www.iied.org/pubs ©International Institute for Environment and Development/Sustainable Food Lab 2012 All rights reserved Chris Docherty is Chairman of the West Indies Sugar & Trading Company Ltd, Barbados and a director of Windward Strategic Ltd based in Bath, UK. His background is in establishing sustainable brands in commodity markets with an emphasis on adding value to agricultural producers in the developing world. He has extensive experience in the sugar and oil industries and has held global positions with Shell International. -

Alcohol Industry in Latin America and the Caribbean

THE ALCOHOL INDUSTRY’S COMMERCIAL AND POLITICAL ACTIVITIES in Latin America and the Caribbean IMPLICATIONS FOR PUBLIC HEALTH ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was written by Katherine Robaina, MPH, University of Auckland (New Zealand) Thomas Babor, PhD, University of Connecticut School of Medicine (USA); Board Member, Global Alcohol Policy Alliance Ilana Pinsky, PhD, Comite para Regulacao do Alcool (CRA) - Faculdade de Ciencias Medicas da Santa Casa de Sao Paulo, (Brazil) Paula Johns, MSc, ACT Health Promotion, Rio de Janeiro (Brazil); Board Member, Global Alcohol Policy Alliance and NCD Alliance The authors wish to thank the following individuals for their advice and peer review of this report: Lucy Westerman (NCD Alliance), Øystein Bakke (GAPA/FORUT), Dr. Beatriz Champagne Healthy Latin America Coalition (CLAS), Prof Rohan Maharaj (Healthy Caribbean Coalition), Sir Trevor Hassell (Healthy Caribbean Coalition), Maisha Hutton (Healthy Caribbean Coalition). The authors wish to thank the following organisations for supporting the publication and dissemination of this report: NCD Alliance, FORUT, Global Alcohol Policy Alliance (GAPA), Healthy Latin America Coalition (CLAS), Healthy Caribbean Coalition, ACT Health Promotion, and Mexico Salud-Hable. © 2020 NCD Alliance, Global Alcohol Policy Alliance, Healthy Latin America Coalition, Healthy Caribbean Coalition Published by the NCD Alliance, Global Alcohol Policy Alliance, Healthy Latin America Coalition, and Healthy Caribbean Coalition Copy editing of this report was carried out by the authors -

Pop the Soda Shop

POP THE SODA SHOP - PRODUCTS Product Name Pkg #Btls Size 18pk RAMUNE CARBONATED SOFT DRINK FROM JAPAN with GLASS BALL ON TOP 18/200ml Glass 18 200ML 18pk RAMUNE GRAPE SODA FROM JAPAN WITH MARBLE STOPPER 18x200ml "Gu-Re-Pu Is Good 4 U" Glass 18 200ML 18pk RAMUNE MELON SODA FROM JAPAN GLASS BALL ON TOP 18/200ml Drink RaMuNe & You'll Be Glass 18 200ML 18pk RAMUNE ORANGE JAPANESE SOFT DRINK with GLASS BALL ON TOP 18/200ml Glass 18 200ML 18pk RAMUNE PLUM SODA w/ MARBLE TOP FROM JAPAN "Ram-Umé"! We Begged Them To Make It! Glass 18 200ML 18pk RAMUNE STRAWBERRY SODA IN GLASS BOTTLE WITH MARBLE ON TOP 18/200ml FROM JAPAN Glass 18 200ML A&W ROOT BEER LONGNECKS 6x4x12oz "That Frosty Mug Taste" But Neither 'Frostie' nor 'Mug' Glass 24 12 OZ ABITA ROOT BEER OF LOUISIANA w/cane sugar "A Cajun Brew" Glass 24 12 OZ ABSTRACT ENERGY 24x12oz LONGNECKS "Makes You Feel Like Salvador Dali With A Paintball Gun" Glass 24 12 OZ ABU ABED MANGO ENERGY DRINK FROM LEBANON 24x266ml "Abu Abed Recommends It!" Glass 24 266ML ABU ABED ORANGE ENERGY DRINK FROM LEBANON 24x266ml "Curls up the ends of your moustache" Glass 24 266ML ABU ABED ORIGINAL ENERGY DRINK FROM LEBANON 24x266ml LONGNECKS "It'll Make Your Fez Glass 24 266ML ABU ABED PEACH ENERGY DRINK FROM LEBANON 24x266ml "Peachy Power From The Land Of Cedars" Glass 24 266ML AJ STEPHANS BIRCH BEER FROM BOSTON 24/12oz "White Birch is the Right Birch" Glass 24 12 OZ AJ STEPHANS BLACK CHERRY FROM CAPE PORPOISE, MAINE "old style" 24x12oz BOTTLES Glass 24 12 OZ AJ STEPHANS BUTTERSCOTCH CREAM "Sweet & Buttery Like A Boston -

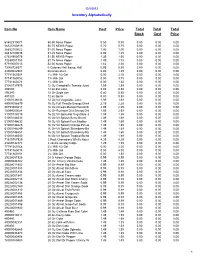

Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Stock Total

12/5/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 65652510071 $0.50 News Paper 0.50 0.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 56525100819 $0.75 NEWS Paper 0.70 0.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 26832100022 $1.00 News Paper 1.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 26832100039 $1.25 News Paper 0.00 1.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 67324900075 $1.50 NEWS Paper 1.35 1.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 73249001758 $1.75 News Paper 1.49 1.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 97910007013 $2.00 News Paper 1.82 2.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 13008728571 0 Calories Half & Half 0.99 0.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 44000022983 0reocakesters 0.80 1.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360304 1% Milk 1/2 Gal 0.00 2.15 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360052 1% Milk Gal 0.00 3.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360274 1% Milk Qrt. 0.00 1.30 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000137975 12 Oz Campbell's Tomato Juice 1.59 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 496580 12 oz diet coke 0.80 0.80 0.00 0.00 0.00 496340 12 Oz Soda can 0.80 0.80 0.00 0.00 0.00 491320 12 oz Sprite 0.80 0.80 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000138033 12 Oz V8 Vegetable Juice 1.59 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 49000036879 16 Oz Full Throttle Energy Drink 2.19 2.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 80793803613 16 Oz Omega Mango Passionfruit Energy 2.09 Drink 2.09 0.00 0.00 0.00 18094000024 16 Oz Rockstar Diet Energy Drink 1.55 2.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000138019 16 Oz V8 SpicyHot Vegetable Juice 1.59 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146533 16 Oz V8 Splash Berry Blend 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146632 16 Oz V8 Splash Fruit Medley 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146625 16 Oz V8 Splash Orange Pineapple 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146649 16 Oz V8 Splash Strawberry Banana 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146557 16 Oz V8 Splash Strawberry Kiwi 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 51000146540 16 Oz V8 Splash Tropical Blend 1.49 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 71610757929 2 Pack Grenadiers Whiffs Natural Imported 4.29 Wrapper 4.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 23269142373 2 vanilla sunday fudge 1.29 1.89 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360168 2% Milk 1/2 Gal 0.00 2.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360014 2% Milk Gal 0.00 4.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 77741360151 2% Milk Qrt. -

“SARSAPARILLA” and “BIRCH BEER” Don't Go to Jetro

ROOT BEER… SEE ALSO “SARSAPARILLA” AND “BIRCH BEER” stop getting canned and get real! SPARKY’S FRESH DRAFT ROOT BEER with Velvet Carbonation IN 22oz BOMBER BOTTLES 12/22oz & 24/12oz Sparkitos!! FAMILY MICROBREW OF PACIFIC GROVE NEAR MONTEREY; 20 YEARS’ WORK; WE THINK THE BEST ROOT BEER EVER; THEY DON’T MAKE ANYTHING BUT ROOT BEER! BAVARIAN NUTMEG IMPORTED VIRGIL’S SPECIAL EDITION ROOT BEER WITH CERAMIC TOP 16/500ml BREWED IN BAVARIA, CERTAINLY THE WORLD’S MOST EXPENSIVE HANDCRAFTED ROOT BEER. ALSO ONE OF THE BEST ROOT BEERS WE’VE TASTED. ABITA ROOT BEER BREWED NEAR NEW ORLEANS WITH PURE LOUISIANA CANE SUGAR 4/6/12oz A CLASSIC AMERICAN HOMETOWN MICROBREW; THE ONLY SOFT DRINK FROM THE ABITA BREWING COMPANY AND ONE OF THE BEST ROOT BEERS OF ALL TIME VIRGIL’S BREWED ROOT BEER 6/4/12oz ALMOST AS GOOD AS THE BAVARIAN NUTMEG; EXPENSIVE BUT A BIT MORE AFFORDABLE EXCELLENT ROOT BEER OLDE RHODE ISLAND MOLASSES BREWED ROOT BEER 24/12oz THE BEST MOLASSES ROOT BEER THERE IS; ALL THE WAY FROM OLDE RHODE ISLAND ROUTE 66 ROOT BEER “my way or the highway” 24/12oz ONE FOR THE ROAD; IF DRINK & DRIVE, DRINK ROUTE 66 ROOT BEER, CREAM,OR, BLK CH, LIME CAPT’N ELI’S ROOT BEER FROM PORTLAND, MAINE ENJOY THE MAINE EVENT IN YOUR OWN HOME; ALL THE WAY FROM THE SHIPYARD BREWERY! DOG N SUDS ROOT BEER from the Dog N Suds Hot Dog Stands of Avon, Indiana 24/12oz & 12/32ozHOT DAWG! YOU’LL FOAM AT THE MOUTH! GALES ROOT BEER MADE BY CHEF GALE GAND 24/12ozMADE BY THE FAMOUS CHICAGO PASTRY CHEF GALE GAND WHO LOVES ROOT BEER! THOMAS KEMPER MICROBREWED ROOT BEER OF SEATTLE 4/6/12oz -

Designing for the Hispanic Demographic P

COVER STORY Crossing Borders: Designing for the Hispanic Demographic By Kimberly J. Decker For despite its oversimplification, Salsa: a case study Contributing Editor the story encapsulates a larger truth So does salsa’s success send a mes- about the changing flavor of North sage to food manufacturers about the undits in search of a pithy American life: Hispanics are the coun- value of courting Hispanic-American metaphor for the Latiniza- try’s largest, fastest-growing ethnic food dollars? Yes, but the message tion of the United States minority. At nearly 40 million strong isn’t as straightforward as manufac- P often seize upon the para- already — 44 million, if you count turers might think. The northward ble of the two competing Puerto Rico — the demographic is spread of Hispanic culture may have condiments. As the story goes, the year increasing at a rate of 7%, or 500,000 set the stage for salsa’s stellar sales, was 1992 and Packaged Facts, New households, annually, outpacing the but Hispanic-American consumers York, reported a 14% rise in salsa sales U.S. Census Bureau’s 1999 forecasts. haven’t necessarily driven those sales over the previous year. But while the And with their growth rate expected themselves. spicy sauce raked in a record $640 mil- to exceed the general population’s by “The biggest consumers of canned lion, sales of ketchup, America’s best at least a factor of 10 in coming years, or jarred salsas are Anglos,” says seller for nearly a century, lagged behind Hispanics will account for one-third Veronica Kraushaar, consultant to Texa at a mere $600 million. -

Annual Report 2010 About Diageo 2010 Was Characterised Diageo Plc Is the World’S Leading Premium Drinks Business with an Outstanding Collection by Variability

Annual Report 2010 About Diageo 2010 was characterised Diageo plc is the world’s leading premium drinks business with an outstanding collection by variability. Diageo’s of beverage alcohol brands across spirits, wines and beer categories. These brands include Johnnie Walker, Guinness, Smirnoff , J&B, Baileys, Tanqueray, Captain Morgan, Crown Royal, brand positions, global Gordon’s , Beaulieu Vineyard and Sterling Vineyards wines. The company also has distribution rights for Jose Cuervo. scale and agility in Diageo is a global company, with its products sold in more than 180 markets around the response to changing world. The management team expects to continue the strategy of investing behind Diageo’s global brands, launching innovative new products, and seeking to expand selectively through conditions delivered partnerships or acquisitions that add long term value for shareholders. The company is listed on both the New York Stock Exchange (DEO) and the London Stock Exchange (DGE). a good performance For more information about Diageo, its people and its brands, visit www. diageo.com. in the year. For Diageo’s global resource that promotes responsible drinking through the sharing of best practice tools, information and initiatives, visit www.DRINKiQ.com. 2 1 3 Go online and view 1 Online Review our 2010 reports 2 Annual Report www.diageo.com 3 Corporate Citizenship Report This is the Annual Report of Diageo plc for the year Diageo’s consolidated fi nancial statements have been ended 30 June 2010 and it is dated 25 August 2010. prepared in accordance with International Financial It includes information that is required by the US Reporting Standards (IFRS) as endorsed and adopted Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for Diageo’s for use in the European Union (EU) and IFRS as issued US fi ling of its Annual Report on Form 20-F.