“Reading” Tool Marks on Furniture by Don Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chainsaw Safety

QUICK CARDTM Chainsaw Safety Operating a chainsaw can be hazardous. Potential injuries can be minimized by using proper personal protective equipment and safe operating procedures. Before Starting a Chainsaw • Check controls, chain tension, and all bolts and handles to ensure that they are functioning properly and that they are adjusted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. • Make sure that the chain is always sharp and that the oil tank is full. • Start the saw on the ground or on another firm support. Drop starting is never allowed. • Start the saw at least 10 feet from the fueling area, with the chain’s brake engaged. Fueling a Chainsaw • Use approved containers for transporting fuel to the saw. • Dispense fuel at least 10 feet away from any sources of ignition when performing construction activities. No smoking during fueling. • Use a funnel or a flexible hose when pouring fuel into the saw. • Never attempt to fuel a running or HOT saw. Chainsaw Safety • Clear away dirt, debris, small tree limbs and rocks from the saw’s chain path. Look for nails, spikes or other metal in the tree before cutting. • Shut off the saw or engage its chain brake when carrying the saw on rough or uneven terrain. • Keep your hands on the saw’s handles, and maintain balance while operating the saw. • Proper personal protective equipment must be worn when operating the saw, which includes hand, foot, leg, eye, face, hearing and head protection. • Do not wear loose-fitting clothing. • Be careful that the trunk or tree limbs will not bind against the saw. -

Hand Saws Hand Saws Have Evolved to fill Many Niches and Cutting Styles

Source: https://www.garagetooladvisor.com/hand-tools/different-types-of-saws-and-their-uses/ Hand Saws Hand saws have evolved to fill many niches and cutting styles. Some saws are general purpose tools, such as the traditional hand saw, while others were designed for specific applications, such as the keyhole saw. No tool collection is complete without at least one of each of these, while practical craftsmen may only purchase the tools which fit their individual usage patterns, such as framing or trim. Back Saw A back saw is a relatively short saw with a narrow blade that is reinforced along the upper edge, giving it the name. Back saws are commonly used with miter boxes and in other applications which require a consistently fine, straight cut. Back saws may also be called miter saws or tenon saws, depending on saw design, intended use, and region. Bow Saw Another type of crosscut saw, the bow saw is more at home outdoors than inside. It uses a relatively long blade with numerous crosscut teeth designed to remove material while pushing and pulling. Bow saws are used for trimming trees, pruning, and cutting logs, but may be used for other rough cuts as well. Coping Saw With a thin, narrow blade, the coping saw is ideal for trim work, scrolling, and any other cutting which requires precision and intricate cuts. Coping saws can be used to cut a wide variety of materials, and can be found in the toolkits of everyone from carpenters and plumbers to toy and furniture makers. Crosscut Saw Designed specifically for rough cutting wood, a crosscut saw has a comparatively thick blade, with large, beveled teeth. -

Tula Adze Download

Australian Artefact Fact Sheet Tula adze Tula adzed dish Tula adze slug Tula adze slug Where? Across most of Australia with a focus on Central and Western Australia. The name tula or tuhla comes from the Wangkangurru people of the Simpson Desert. What? The tula adze is a hafted flaked stone tool mostly used for wood working (scraping, adzing and hardwood such as Acacias and Eucalypts. They were also used to butcher animals and to chop plants. When they are used to adze hard wood they blunt quickly and were then resharpened repeatedly by knocking off small flakes along the working edge. In archaeological sites they are usually found as exhausted slugs that have been removed from their hafting, discarded and then replaced. When? Tools such as tulas are rare in archaeological sites and especially places that can be dated. This has meant that there are small numbers that have been securely dated. The oldest dated tula adzes come from rockshelters in the Hamersley Ranges near Newman and Packsaddle dated to between 3,700 and 3,500 years ago. How? Tula adzes are made by flaking a core. They have a wide flat top (platform) that allows easy hafting and they have a curved shaped back (convex). The adzes were usually hafted into the ends of a wooden stick or spear thrower encasing the end of the stick/spear thrower in a resin glue made from spinifex or grevillea resin, kangaroo poo and sand. It took about two tulas to make a boomerang and an undecordated spear thrower would take about eight hours to make with a tula adze. -

The Bow and Arrow in the Book of Mormon

The Bow and Arrow in the Book of Mormon William J. Hamblin The distinctive characteristic of missile weapons used in combat is that a warrior throws or propels them to injure enemies at a distance.1 The great variety of missiles invented during the thousands of years of recorded warfare can be divided into four major technological categories, according to the means of propulsion. The simplest, including javelins and stones, is propelled by unaided human muscles. The second technological category — which uses mechanical devices to multiply, store, and transfer limited human energy, giving missiles greater range and power — includes bows and slings. Beginning in China in the late twelfth century and reaching Western Europe by the fourteenth century, the development of gunpowder as a missile propellant created the third category. In the twentieth century, liquid fuels and engines have led to the development of aircraft and modern ballistic missiles, the fourth category. Before gunpowder weapons, all missiles had fundamental limitations on range and effectiveness due to the lack of energy sources other than human muscles and simple mechanical power. The Book of Mormon mentions only early forms of pregunpowder missile weapons. The major military advantage of missile weapons is that they allow a soldier to injure his enemy from a distance, thereby leaving the soldier relatively safe from counterattacks with melee weapons. But missile weapons also have some signicant disadvantages. First, a missile weapon can be used only once: when a javelin or arrow has been cast, it generally cannot be used again. (Of course, a soldier may carry more than one javelin or arrow.) Second, control over a missile weapon tends to be limited; once a soldier casts a missile, he has no further control over the direction it will take. -

Comparative Study of NZ Pine & Selected SE Asian Species

(FRONT COVER) A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF NEW ZEALAND PINE AND SELECTED SOUTH EAST ASIAN SPECIES (INSIDE FRONT COVER) NEW ZEALAND PINE - A RENEWABLE RESOURCE NZ pine (Pinus radiata D. Don) was introduced to New Zealand (NZ) from the USA about 150 years ago and has gained a dominant position in the New Zealand forest industry - gradually replacing timber from natural forests and establishing a reputation in international trade. The current log production from New Zealand forests (1998) is 17 million m3, of which a very significant proportion (40%) is exported as wood products of some kind. Estimates of future production indicate that by the year 2015 the total forest harvest could be about 35 million m3. NZ pine is therefore likely to be a major source of wood for Asian wood manufacturers. This brochure has been produced to give prospective wood users an appreciation of the most important woodworking characteristics for high value uses. Sponsored by: Wood New Zealand Ltd. Funded by: New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade Written by: New Zealand Forest Research Institute Ltd. (Front page - First sheet)) NEW ZEALAND PINE - A VERSATILE TIMBER NZ pine (Pinus radiata D.Don) from New Zealand is one of the world’s most versatile softwoods - an ideal material for a wide range of commercial applications. Not only is the supply from sustainable plantations increasing, but the status of the lumber as a high quality resource has been endorsed by a recent comparison with six selected timber species from South East Asia. These species were chosen because they have similar end uses to NZ pine. -

COTI Guide to Crew Leadership for Trails

COTI Guide to Crew Leadership for Trails Produced by Colorado Outdoor Training Initiative (COTI) Funded in part by Great Outdoors Colorado (GOCO) through the Colorado State Parks Trails Program. Second printing 2006 Acknowledgements THANK YOU COTI would like to acknowledge the people and organizations that volunteered their time and resources to the research, review, editing and piloting of these training materials. The content and illustrations of this document is a compilation of pre-existing sources, with a majority of the information provided by Larry Lechner, Protected Area Management Services; Crew Leader Manual, 5th Ed., Volunteers for Outdoor Colorado; Trail Construction and Maintenance Notebook. 2000 Ed. USDA Forest Service; and all of the other resources that are referenced at the end of each section. The COTI Instructor’s Guide to Teaching Crew Leadership for Trails was open to a statewide review prior to pilot training and publication. COTI would like to thank everyone who dedicated time to the review process. The following people provided valuable feedback on the project. CURRICULUM COMMITTEE MEMBERS Project Leader: Terry Gimbel, Colorado State Parks Final content editing 2005 Edition: Pamela Packer, COTI 2006 Edition: Hugh Duffy and Hugh Osborne, National Park Service; Mick Syzek, Continental Divide Trail Alliance Alice Freese, Colorado Outdoor Training Initiative Scott Gordon, Bicycle Colorado Sarah Gorecki, Colorado Fourteeners Initiative Jon Halverson, USFS-Medicine Bow-Routt National Forest David Hirt, Boulder County -

Tools of the Cabinetmaker, but Also Like the Cartwright, the Hatchet (Handbeil) and the Drawknife (Schneidemesser)

CHAPTER FIVE The Chairmaker The chairmaker bears the name in common with English chairmakers presumably because his trade is originally transplanted from England to Germany, or because several types of chairs that are made in his workshop have been common first in England. In the making of chairs, the settee (Canape), and sofa, he wields not only the plane and other tools of the cabinetmaker, but also like the cartwright, the hatchet (Handbeil) and the drawknife (Schneidemesser). I. In most regions, and especially in the German coastal cities, chairmakers make their chairs out of red beech wood, in Magdeburg out of linden wood, and in Berlin out of serviceberry wood (Elsenholz). Red beech is lacking in our area, and the cabinetmaker, who before the arrival to Berlin of chairmakers that made wooden chair frames, chose therefore serviceberry wood in place of red beech. Likewise the chairmakers, when they arrived in Berlin, found that circumstances also compelled them to build their chairs out of serviceberry wood. If the customer explicitly requires it, and will pay especially for it, they sometimes build chairs out of walnut, plum wood, pearwood, and mahogany wood, and for very distinguished and wealthy persons out of cedarwood. The chairmaker obtains the serviceberry wood partly in boards that are one to five inches thick and partly in logs. The farmer in the [town of] Mark Brandenburg brings this wood, partly in logs and also in boards, to Berlin to sell, but the strongest and best comes from Poland. If the wood has not sufficiently dried when purchased by the chairmaker it must stay some time longer and properly dry. -

Carpenters of Japanese Ancestry in Hawaii Hisao Goto Kazuko

Craft History and the Merging of Tool Traditions: Carpenters of Japanese Ancestry in Hawaii Hisao Goto Kazuko Sinoto Alexander Spoehr For centuries the Japanese have made extensive use of wood as the main raw material in the construction of houses and their furnishings, temples, shrines, and fishing boats. As a wood-worker, the carpenter is one of the most ancient of Japanese specialists. He developed a complex set of skills, a formidable body of technical knowledge, and a strong tradition of craftsmanship to be seen and appreciated in the historic wood structures of contemporary Japan.1 The first objective of this study of carpenters of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii is to throw light on how the ancient Japanese craft of carpentry was transplanted from Japan to a new social, cultural, and economic environment in Hawaii through the immigration of Japanese craftsmen and the subsequent training of their successors born in Hawaii. Despite its importance for the understanding of economic growth and develop- ment, the craft history of Hawaii has not received the attention it deserves. The second objective of the study is more anthropological in nature and is an attempt to analyze how two distinct manual tool traditions, Japanese and Western, met and merged in Hawaii to form a new composite tool tradition. This aspect of the study falls in a larger field dealing with the history of technology and of tool traditions in general. Carpentry today, both in Japan and in the United States, relies heavily on power rather than hand tools. Also, carpenters tend to be specialized, and construction is to a major degree a matter of assembling prefabricated parts. -

Code of Practice for Wood Processing Facilities (Sawmills & Lumberyards)

CODE OF PRACTICE FOR WOOD PROCESSING FACILITIES (SAWMILLS & LUMBERYARDS) Version 2 January 2012 Guyana Forestry Commission Table of Contents FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Wood Processing................................................................................................................................. 8 1.2 Development of the Code ................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Scope of the Code ............................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Objectives of the Code ...................................................................................................................... 10 1.5 Implementation of the Code ............................................................................................................. 10 2.0 PRE-SAWMILLING RECOMMENDATIONS. ............................................................................................. 11 2.1 Market Requirements ....................................................................................................................... 11 2.1.1 General .......................................................................................................................................... -

Building Practices and Carpenters' Tools That Created Alexandria's Kent Plantation House

Building Practices and Carpenters' Tools That Created Alexandria's Kent Plantation House By N. H. Sand and Peter Koch SouthernForest ExperimentStation Forest Service. U. S. Departmentof Agriculture I t is the year 1796or thereabouts. ily, and he succeeds so well that designed and made with good Louisiana is a Spanish colony with the dwelling still remains sound and materials. French traditions and culture. attractive after 175 years, a very Now known (from a later owner) Pierre Baillio II, of a prominent great age for a house in America. asthe Kent PlantationHouse, Bail- French family, has a sizeable grant To reach it takes good luck-escape lio's home has recently beenmade of land along the Red River near from fire, flood and the Civil War. into a museum in Alexandria, a a small town called EI Rapido. Continuous occupancy and the care short distance from where it was Baillio undertakes to have a that goes with it also helps. Most originally constructed. There it house built for himself and his fam- of all, the house must be soundly standsas testimony to the skins of early Louisiana carpenter crafts- men. In contrast to architects, who seemto leapinto print with no great difficulty, carpenters are a silent tribe. They come to the job with their tool chests, exercise many skins of construction and some of design, and then pass on. Often their works are their only record. Occasionally some tools survive and, after generationsof neglectand abuse,these may find their way int() antique shopsor museums. Thus it is difficult to speakin de- tail of the builders of any given house. -

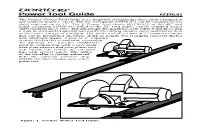

Power Tool Guide 05J50.01

Power Tool Guide 05J50.01 The Veritas® Power Tool Guide is a collapsible straightedge that can be clamped to any material under 1" thick. The 52" tool guide (05J50.03) can be clamped across sheet material up to 52". The 8' Power Tool Guide (05J50.01), or the 48" tool guide extension (05J50.04) added to the 52" tool guide, can be clamped across sheet material up to 100". The advantage this guide has over other 8' guides is that it may be dismantled quickly and easily for cutting smaller sheet material as well as for easier storage or transport. The guide includes a pair of 1" capacity clamps that can be positioned anywhere along its length. For clamping material thicker than plywood sheets, a pair of 2" capacity clamps (05J50.09) is available separately. An optional 12" traveller (05J50.02) used in conjunction with a user-made base plate ensures that your power tool will effortlessly follow the intended line with greater safety. The utility of the traveller is further enhanced with the optional position stop (05J50.10) that clamps onto either guide rail. Figure 1: Veritas® Power Tool Guide. Safety Rules These safety instructions are meant to complement those that came with your power tool. We suggest that you reread those, in addition to these listed here before you begin to use this product. To use this product safely, always follow both sets of safety and general instructions. 1. Read the manual. Learn the tool’s applications and limitations as well as the specific hazards related to the tool. -

Spring 2016 RECENT PUBLICITY HIGHLIGHTS

Tuttle New Titles and Backlist Highlights Spring 2016 RECENT PUBLICITY HIGHLIGHTS North Korea Confidential…page 62 “‘North Korea Confidential’ gives us a deeply informed close-up.” —New York Times Japan Restored…page 62 “Labor economist Prestowitz (Rogue Nation) projects visions of Japan’s future in this well-handled study of sensitive politico-economic issues disguised as a love letter to the country.” —Publishers Weekly All About the Philippines…page 57 “The large format and attractive, cartoonlike illustrations provide an inviting look at a country not often included in many other resources for children.” —Kirkus The Cambodian Dancer…page 57 Once Upon A Time in Japan…page 57 “A general purchase for libraries needing picture books on Cambodian “Will likely delight young readers.” culture and history and those looking —Booklist to diversify their shelves.” —School Library Journal w w AWARD WINNERS! Evergreen Medal For The Chinese American Creative Child Magazine Creative Child Magazine World Peace Librarians Association (CALA) —2015 Creative Play —2015 Preferred Choice Award —Silver Best Book Award Recipients of the Year Award MY FIRST ORIGAMI KIT THE PEACE TREE FROM —Honorable Mention ORIGAMI TOY MONSTERS KIT page 27 HIROSHIMA MEI-MEI’S LUCKY BIRTHDAY page 27 page 57 NOODLES page 56 FRONT COVER: Image from Floating World Japanese Prints Coloring Book,PAGEs"!#+#/6%2)MAGEFROMEco Living Japan, page 37 Don’t Miss . Contents New Titles and Backlist Highlights Floating World Japanese Prints Coloring Book…3 Art, Antiques & Collectibles. 2 Religion & Health . 10 Culture, Graphic Novels & Humor . 12 Crafts & Origami . 14 Cooking . 28 Japanese Tattoos…5 Travel . 32 Architecture, Gardening & Interior Design .