CASE STUDY—What Happened to Kmart?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Retail Sector on Long Island Overlooked… Undervalued… Essential!

The Retail Sector on Long Island Overlooked… Undervalued… Essential! A Preliminary Report from the Long Island Business Council May 2021 Long Island “ L I ” The Sign of Success 2 | The Retail Sector on Long Island: Overlooked, Undervalued, Essential! Long Island Business Council Mission Statement The Long Island Business Council (LIBC) is a collaborative organization working to advocate for and assist the business community and related stakeholders. LIBC will create an open dialogue with key stakeholder groups and individuals to foster solutions to regional and local economic challenges. LIBC will serve as a community-focused enterprise that will work with strategic partners in government, business, education, nonprofit and civic sectors to foster a vibrant business climate, sustainable economic growth and an inclusive and shared prosperity that advances business attraction, creation, retention and expansion; and enhances: • Access to relevant markets (local, regional, national, global); • Access to a qualified workforce (credentialed workforce; responsive education & training); • Access to business/economic resources; • Access to and expansion of the regional supply chain; • A culture of innovation; • Commitment to best practices and ethical operations; • Adaptability, resiliency and diversity of regional markets to respond to emerging trends; • Navigability of the regulatory environment; • Availability of supportive infrastructure; • An attractive regional quality of life © 2021 LONG ISLAND BUSINESS COUNCIL (516) 794-2510 [email protected] -

What Went Wrong with Kmart?

What Went Wrong With Kmart? An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by Jacqueline Matyk Thesis Advisor Dr. Mark Myring Ball State University Muncie, Indiana December 2003 Graduation: December 21, 2003 Table of Contents Abstract. ........... ..................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................ 4 History ofKnlart .......................................................................... 4 Overview ofKnlart ................................... .................................. 6 Kmart's Problems That Led to Bankruptcy ....... ............... 6 Major Troubles in 2001 .................................................................. 7 2002 and Bankruptcy ..................................................................... 9 Anonymous Letters Lead to Stewardship Review .................................... 9 Emergence from Bankruptcy........................................................... 12 Charles Conaway's Role ................................................................ 14 The Case Against Enio Montini and Joseph Hofmeister ........................... 17 Conclusion.. ............................................................................. 19 Works Cited ............................................................................. 20 2 Abstract This paper provides an in depth look at Krnart Corporation. I will discuss how the company began its operations as a small five and dime store in Michigan and grew into one of the nation's largest retailers. -

Faulkner's Wake: the Emergence of Literary Oxford

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2004 Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford John Louis Fuller Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Fuller, John Louis, "Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford" (2004). Honors Theses. 2005. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2005 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faulkner’s Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford Bv John L. Fuller A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford April 2005 Advisor; Dr. Judson D. Wafson -7 ■ / ^—- Reader: Dr. Benjamin F. Fisher y. Reader: Dr. Andrew P. D^rffms Copyright © by John L. Fuller All Rights Reserved 1 For my parents Contents Abstract 5 I The Beginnings 9 (4Tell About the South 18 A Literary Awakening 25 II If You Build It, They Will Come 35 An Interview with Pochard Howorth 44Football, Faulkner, and Friends 57 An Interview with Barry Hannah Advancing Oxford’s Message 75 An Interview with Ann J. Abadie Oxford Tom 99 An Interview with Tom Franklin III Literary Grounds 117 Works cited 120 Abstract The genesis of this project was a commercial I saw on television advertising the University of Mississippi. “Is it the words that capture a place, or the place that captures the words?” noted actor and Mississippi native Morgan Freeman asked. -

Scrip Order Form

St. Thomas Aquinas SCRIP ORDER FORM Thank you! Your support is greatly appreciated! Please remember that we can sell only the amounts listed on the order form. Name:_______________________________________________Phone:___________________Date:_______________ Check# :_________________Amount:__________________ * Please make checks payable to: St. Thomas Aquinas * Filled by__________NEEDS:________________________________________________________________________ Retailer Profit Card Qty. Total Retailer Profit Card Qty. Total (c.o.a.) = certificate on account for Amount (c.o.a.) = certificate on for Amount school account school $5.00 $100 Claire’s $0.90 $10 All Seasons Gutter/New All Seasons Gutter/Topper $10.00 $100 Cold Stone $0.80 $10 Creamery American Eagle Outfitters $2.00 $25 Courtyard/Marriott $6.00 $50 Applebees $2.00 $25 Critter $0.50 $10 Nation(Dyvig’s) Arby’s $0.80 $10 Barnes & Noble/B. Dalton $1.00 $10 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $1.00 $25 Barnes & Noble/B. Dalton $2.50 $25 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $2.50 $50 Bath and Body Works $1.30 $10 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $5.00 $100 Bath and Body Works $3.25 $25 Dillard’s $2.25 $25 Bed, Bath and Beyond $1.75 $25 Dress Barn $2.00 $25 Best Buy $0.50 $25 Express $2.50 $25 Best Buy $2.00 $100 Fareway $0.50 $25 Big Time Cinema (Fridley’s) $1.00 $10 Fareway $1.00 $50 Borders/Waldenbooks $0.90 $10 Fareway $2.00 $100 Borders/Waldenbooks $2.25 $25 Fairfield Inn/Marriott $6.00 $50 Build-A-Bear $2.00 $25 Fazoli’s $1.75 $25 Burger King $0.50 $10 Finish Line $2.50 $25 Cabela’s $3.25 $25 Flower Cart (c.o.a.) $1.25 $25 Carlos O’Kelly $0.90 $10 Foot Locker $2.25 $25 Casey’s $0.30 $10 Fuhs Pastry $1.00 $10 Casey’s $0.75 $25 Gap/Old $2.25 $25 Navy/Banana Republic Casey’s $1.50 $50 GameStop $0.75 $25 Cheesecake Factory $1.25 $25 Gerber’s (c.o.a.) $2.50 $50 Chili’s/Macaroni Grill/On the $2.75 $25 Gerber’s (c.o.a.) $5.00 $100 Boarder Chuck E. -

We Help Our Friends Grow We Want to Help You Make More Meaningful Connections Through: PRINT Online • Social Media Partnerships • Email Marketing

2021 Media Kit Inspirational Art, Crafts & Lifestyle Magazines We Help Our Friends Grow We want to help you make more meaningful connections through: PRINT Online • Social Media Partnerships • Email Marketing A Somerset Holiday Art Journaling Art Quilting Studio Belle Armoire Jewelry GreenCraft In Her Studio Mingle Somerset Studio Willow and Sage & Special Editions 2 About the Publisher When it comes to the art of crafting, no one does it better than Stampington & Company. — Mr. Magazine™ Samir Husni Since 1994, Stampington & Company has been a Leading Source of Information and Inspiration for Artists and Crafts Lovers, Storytellers, and Photographers Around the World Known for its stunning full-color photography and step-by-step instructions, the company’s magazines provide a forum for both professional artists and hobbyists looking to share their beautiful handmade creations, tips, and techniques with one another. Our community loves to immerse themselves in our magazines. These magazines are meant to be curled up with, kept in libraries as a resource to reference, and to share years later with friends and family. The enthusiasm of our readers doesn’t end here. Our community loves to blog and post pictures across social media from a wide range of channels, showing off our exclusive stories and soul-stirring photography. Our Social Profile 100K+ Facebook fans 94K+ Instagram followers 2.7m Pinterest monthly viewers 25K+ Twitter followers Media Kit 3 What’s Inside This media kit contains a wealth of information. Take a moment to read each of our publication descriptions and audience information to find the perfect advertising venue for your products. -

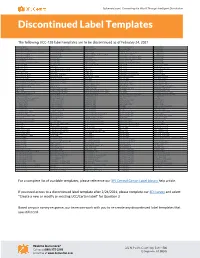

Discontinued Label Templates

3plcentral.com | Connecting the World Through Intelligent Distribution Discontinued Label Templates The following UCC-128 label templates are to be discontinued as of February 24, 2021. AC Moore 10913 Department of Defense 13318 Jet.com 14230 Office Max Retail 6912 Sears RIM 3016 Ace Hardware 1805 Department of Defense 13319 Joann Stores 13117 Officeworks 13521 Sears RIM 3017 Adorama Camera 14525 Designer Eyes 14126 Journeys 11812 Olly Shoes 4515 Sears RIM 3018 Advance Stores Company Incorporated 15231 Dick Smith 13624 Journeys 11813 New York and Company 13114 Sears RIM 3019 Amazon Europe 15225 Dick Smith 13625 Kids R Us 13518 Harris Teeter 13519 Olympia Sports 3305 Sears RIM 3020 Amazon Europe 15226 Disney Parks 2806 Kids R Us 6412 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13651 Sears RIM 3105 Amazon Warehouse 13648 Do It Best 1905 Kmart 5713 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13652 Sears RIM 3206 Anaconda 13626 Do It Best 1906 Kmart Australia 15627 Orchard Supply 1705 Sears RIM 3306 Associated Hygienic Products 12812 Dot Foods 15125 Lamps Plus 13650 Orchard Supply Hardware 13115 Sears RIM 3308 ATTMobility 10012 Dress Barn 13215 Leslies Poolmart 3205 Orgill 12214 Shoe Sensation 13316 ATTMobility 10212 DSW 12912 Lids 12612 Orgill 12215 ShopKo 9916 ATTMobility 10213 Eastern Mountain Sports 13219 Lids 12614 Orgill 12216 Shoppers Drug Mart 4912 Auto Zone 1703 Eastern Mountain Sports 13220 LL Bean 1702 Orgill 12217 Spencers 6513 B and H Photo 5812 eBags 9612 Loblaw 4511 Overwaitea Foods Group 6712 Spencers 7112 Backcountry.com 10712 ELLETT BROTHERS 13514 Loblaw -

The New Borders and Waldenbooks Visa Card

Double Rewards, One Card - The New Borders And Waldenbooks Visa Card Borders Group Inc., Bank One Combine Borders, Waldenbooks Rewards Programs WILMINGTON, Del. - July 31, 2003 - Earning rewards just became twice as nice for cardmembers of Borders* Platinum Visa* Card and Waldenbooks* Preferred Reader* Platinum Visa Card. Borders Group, Inc. [NYSE: BGP] and Bank One [NYSE: ONE] today announced that they've enhanced the Borders Platinum Visa Card to include Waldenbooks rewards. The new card is appropriately named the Borders and Waldenbooks Visa Card. The new card enables cardmembers to earn two points for every dollar in purchases at Borders and Waldenbooks stores, as well as their Web sites, and one point for every dollar in all other purchases. Every time cardmembers accumulate just 500 points, they will automatically receive a $5 Store Reward Certificate valid at any Borders or Waldenbooks store. Previously, cardmembers of Borders Platinum Visa Card could only earn double points for their purchases at Borders, and Waldenbooks Preferred Reader Platinum Visa cardmembers could only earn one point for every $5 in card purchases. In addition, consumers had to be enrolled in the Waldenbooks Preferred Reader Program to be eligible for the Waldenbooks credit card product. "We listened to our customers, which is why we worked with Bank One to combine both brands into one product offering that cardmembers can use at our more than 1,100 stores across the country," said Mike Spinozzi, executive vice president and chief marketing officer of Borders Group. "This is a great way for us to thank our customers for their loyalty and help them reap additional benefits from their everyday purchases." New cardmembers who apply for the card online or via an application available at any Borders or Waldenbooks store will receive a $20 gift card after their first purchase, which can be redeemed at any Borders or Waldenbooks store. -

Property Summary As of 12/31/05

Property Summary As of 12/31/05 Total Shopping Center GLA: Company Owned GLA Annualized Base Rent Year Constructed / Anchors: Acquired / Year of Total Non- Latest Renovation or Number Anchor Company Anchor Anchor Property Location Expansion (3) of Units Owned Owned GLA GLA Total Total Leased Occupancy Total PSF Anchors [8] Alabama Cox Creek Plaza Florence, AL 1984/1997/2000 5 102,445 92,901 195,346 7,600 202,946 100,501 100,501 100.0%$ 706,262 $ 7.03 Goody's, Toy's R Us, Old Navy, Home Depot [1] Total/Weighted Average 5 102,445 92,901 195,346 7,600 202,946 100,501 100,501 100.0%$ 706,262 $ 7.03 Florida Coral Creek Shops Coconut Creek, FL 1992/2002/NA 34 42,112 42,112 67,200 109,312 109,312 105,712 96.7%$ 1,492,867 $ 14.12 Publix Crestview Corners Crestview, FL 1986/1997/1993 15 79,603 79,603 32,015 111,618 111,618 109,218 97.8%$ 508,024 $ 4.65 Big Lots, Beall's Outlet, Ashley Home Center Kissimmee West Kissimmee, FL 2005/2005 19 184,600 67,000 251,600 48,586 300,186 115,586 102,704 88.9%$ 1,223,870 $ 11.92 Jo-Ann, Marshalls,Target [1] Lantana Shopping Center Lantana, FL 1959/1996/2002 22 61,166 61,166 61,848 123,014 123,014 123,014 100.0%$ 1,282,015 $ 10.42 Publix Marketplace of Delray [11] Delray Beach, FL 1981/2005/NA 48 116,469 116,469 129,911 246,380 246,380 217,455 88.3%$ 2,537,850 $ 11.67 David Morgan Fine Arts, Office Depot, Winn-Dixie Martin Square [11] Stuart, FL 1981/2005/NA 13 291,432 291,432 35,599 327,031 327,031 327,031 100.0%$ 2,032,426 $ 6.21 Home Depot, Howards Interiors, Kmart, Staples Mission Bay Plaza Boca Raton, FL -

Barnes and Noble History

Wingler 1 Brandon Wingler April 15th, 2015 Barnes & Noble: A Brief History from Reconstruction to the 21st Century Part I: The Origins of Barnes & Noble The story of Barnes & Noble starts as far back as 1873 in the modest town of Wheaton, Illinois, located about twenty-five miles west of Chicago. The area had first been settled in 1831 by Erastus Gary and, starting in 1839, his former neighbors Jesse and Warren Wheaton laid claim to about a thousand acres in what is now the town of Wheaton, Illinois. The Galena & Chicago Union Railroad first appeared in the town in 1849 and contributed to a small but noticeable rise in traffic and trade. In the first few years of the 1870s, Wheaton eclipsed the one- thousand mark for total population.1 In 1873, Charles Montgomery Barnes decided to open up a small bookstore in Wheaton. With the nearby Wheaton College and a new public school that had opened in 1874, Barnes’s business had a steady rate of demand for school books. It was only a short three years before Barnes elected to move his business eastward to Chicago and set up shop as C.M. Barnes & Company. After a couple of decades, Barnes decided to focus exclusively on school textbooks and reorganized the business in 1894. His son, William Barnes, and William’s father-in-law, John Wilcox, joined the company in the mid-1880s. Charles retired from the business in 1902 1 “Wheaton, IL.,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, accessed February 6th, 2015, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1350.html. -

YIR Retail Bankruptcy

The Year Brick & Mortar Got a Bankruptcy Makeover What Fashion and Luxury Goods Companies Need to Know About Restructuring and Bankruptcy Los Angeles / New York / San Francisco / Washington, DC arentfox.com Introduction Understanding the Issues, Causes, Tools for Distressed Retail Situations & What Lies Ahead for 2018 2017 was a watershed year for retail bankruptcies. More than 300 retailers fi led for bankruptcy in 2017,1 many being smaller “Mom & Pop” shops. As of the end of 2017, there have been no less than thirty major retail bankruptcy fi lings, exceeding the total number of major retail cases fi led in 2016.2 As of the end of the third quarter of 2017, more than 6,400 store closings occurred—triple the number of closings during the fi rst half of 2016.3 Analysts predict the total number of storing closings for the year ending 2017 will be between approximately 8,600 to more than 9,000, well above the 6,200 closings during the 2008 fi nancial crisis, and signifi cantly more than that of 2016.4 At this rate, at least 10% of the total physical US retail landscape is estimated to have closed during 2017. These cutbacks resulted in an estimated 76,084 job cuts by retail employers in 2017, a 26% increase over 2016, unseen in any other industry in 2017.5 Retailers are confronted with market pressures and unique legal issues in bankruptcy that make successful reorganizations more diffi cult to attain. It is clear that the trend of failing retailers will intensify before it improves. -

Year Developed Or Leasable Area Percent Leased Major

YEAR DEVELOPED LEASABLE PERCENT OR AREA LEASED MAJOR LEASES LOCATION PORTFOLIO ACQUIRED (SQ.FT.) (1) TENANT NAMEGLA TENANT NAME GLA TENANT NAME GLA BURLINGTON COAT BROWNSVILLE 2005 235,959 95.9 80,274 TJ MAXX 28,460 MICHAELS 21,447 FACTORY BURLESON 2011 280,430 100.0 KOHL'S 86,584 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 30,187 TJ MAXX 28,000 ASHLEY FURNITURE CONROE 2015 289,322 100.0 48,000 TJ MAXX 32,000 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 30,183 HOMESTORE CORPUS CHRISTI 1997 159,329 100.0 BEST BUY 47,616 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 34,000 BED BATH & BEYOND 26,300 DALLAS KIR 1998 83,867 97.4 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 28,160 OFFICEMAX 23,500 BIG LOTS 18,007 VITAMIN COTTAGE DALLAS PRU 2007 171,143 93.5 CVS 16,799 11,110 ULTA 3 10,800 NATURAL FOOD FORT WORTH 2015 291,121 93.6 MARSHALLS 38,032 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 30,079 OFFICE DEPOT 20,000 HOBBY LOBBY / SPROUTS FARMERS FRISCO 2006 231,697 96.9 81,392 HEMISPHERES 50,000 26,043 MARDELS MARKET GEORGETOWN OJV 2011 115,416 79.7 DOLLAR TREE 13,250 CVS 10,080 GRAND PRAIRIE 2006 244,264 90.5 24 HOUR FITNESS 30,000 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 29,931 MARSHALLS 28,000 HOUSTON 2005 41,576 100.0 MICHAELS 21,531 HOUSTON OIP 2006 237,634 100.0 TJ MAXX 32,000 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 30,187 BED BATH & BEYOND 30,049 HOUSTON 2015 144,055 100.0 BEST BUY 35,317 HOME GOODS 31,620 BARNES & NOBLE 25,001 HOUSTON 2015 350,836 97.7 MARSHALLS 30,382 BED BATH & BEYOND 26,535 PARTY CITY 23,500 HOUSTON 2013 149,065 93.1 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 30,176 OLD NAVY 19,222 PETCO 13,500 SPROUTS FARMERS HOUSTON 2015 165,268 98.1 29,582 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 26,000 GOODY GOODY LIQUOR 23,608 MARKET -

Ieg Sponsorship Report Ieg Sponsorship Report the Latest on Sports, Arts, Cause and Entertainment Marketing

IEG SPONSORSHIP REPORT IEG SPONSORSHIP REPORT THE LATEST ON SPORTS, ARTS, CAUSE AND ENTERTAINMENT MARKETING MONTH 00, 2013 WWW.IEGSR.COM RETAIL ACADEMY SPORTS GETS SCHOOLED ON SPONSORSHIP Retailer borrows equity from pro sports teams and college athletic programs to build local presence. Academy Sports + Outdoors is breathing new life into the otherwise lackluster sporting goods category. While The Sports Authority, Inc. and Dick’s Sporting Goods, Inc. are both active sponsors—and to a lesser extent, Foot Locker, Inc.—other players have largely dabbled in sponsorship based on the ups and downs in the economy. In a breath of fresh air, Academy Sports has significantly expanded its sponsorship portfolio over the last two years to support its growth ambitions. The Texas-based chain—which operates roughly 170 stores in 13 southeast and Midwestern states—is aligning WHERE SPORTS EQUIPMENT RETAILERS SPEND MONEY with pro sports teams and collegiate athletic programs to build presence in new markets. The company over the last three months has signed more than 10 deals in Florida, Kansas, North Carolina, Tennessee and other states. Case in point: Academy last month announced a multiyear agreement with The University of Memphis athletics to support the opening of its first Memphis-area store. The retailer in August inked new deals with two schools in Florida and three in Kansas. In Florida, Academy partnered with the University of ©2013 IEG, LLC. All rights reserved. Florida and Florida State University to support its growth in North Florida. The company—which operates two stores in Jacksonville—plans to open a third in the city by the end of the year.