Sanctuary City Pynchon's Subjunctive New York in Bleeding Edge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metamodern Writing in the Novel by Thomas Pynchon

INTERLITT ERA RIA 2019, 24/2: 495–508 495 Bleeding Edge of Postmodernism Bleeding Edge of Postmoder nism: Metamodern Writing in the Novel by Thomas Pynchon SIMON RADCHENKO Abstract. Many different models of co ntemporary novel’s description arose from the search for methods and approaches of post-postmodern texts analysis. One of them is the concept of metamodernism, proposed by Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker and based on the culture and philosophy changes at the turn of this century. This article argues that the ideas of metamodernism and its main trends can be successfully used for the study of contemporary literature. The basic trends of metamodernism were determined and observed through the prism of literature studies. They were implemented in the analysis of Thomas Pynchon’s latest novel, Bleeding Edge (2013). Despite Pynchon being usually considered as postmodern writer, the use of metamodern categories for describing his narrative strategies confirms the idea of the novel’s post-postmodern orientation. The article makes an endeavor to use metamodern categories as a tool for post-postmodern text studies, in order to analyze and interpret Bleeding Edge through those categories. Keywords: meta-modernism; postmodernism; Thomas Pynchon; oscillation; new sincerity How can we study something that has not been completely described yet? Although discussions of a paradigm shift have been around long enough, when talking about contemporary literary phenomena we are still using the categories of feeling rather than specific instruments. Perception of contemporary lit era- ture as post-postmodern seems dated today. However, Joseph Tabbi has questioned the novelty of post-postmodernism as something new, different from postmodernism and proposes to consider the abolition of irony and post- modernism (Tabbi 2017). -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

About Fresh Kills

INTERNATIONAL DESIGN COMPETITION : 2001 ABOUT FRESH KILLS Fresh Kills Landfill is located on the western shore of Staten Island. Approximately half the 2,200-acre landfill is composed of four mounds, or sections, identified as 1/9, 2/8, 3/4 and 6/7 which range in height from 90 feet to approximately 225 feet. These mounds are the result of more than 50 years of landfilling, primarily household waste. Two of the four mounds are fully capped and closed; the other two are being prepared for final capping and closure. Fresh Kills is a highly engineered site, with numerous systems put in place to protect public health and environmental safety. However, roughly half the site has never been filled with garbage or was filled more than twenty years ago. These flatter areas and open waterways host everything from landfill infrastructure and roadways to intact wetlands and wildlife habitats. The potential exists for these areas, and eventually, the mounds themselves, to support broader and more active uses. With effective preparation now, the city can, over time, transform this controversial site into an important asset for Staten Island, the city and the region. Before dumping began, Fresh Kills Landfill was much like the rest of northwest Staten Island. That is, most of the landfill was a salt or intertidal marsh. The topography was low-lying, with a subsoil of clay and soils of sand and silt. The remainder of the area was originally farmland, either actively farmed, or abandoned and in stages of succession. Although Fresh Kills Landfill is not a wholly natural environment, the site has developed its own unique ecology. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. However, the thesis incorporates, to the extent indicated below, material already submitted as part of required coursework and/ or for the degree of: Masters in English Literary Studies, which was awarded by Durham University. Sign ature: Incorporated material: Some elements of chapter three, in particular relating to the discussion of teeth and dentistry, formed part of an essay submitted for my MA at Durham CniYersiry. This material has, however, been significantly reworked and re,,ised srnce then. Dismantling the face in Thomas Pynchon’s Fiction Zachary James Rowlinson Submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex November 2015 i Summary Thomas Pynchon has often been hailed, by those at wont to make such statements, as the most significant American author of the past half-century. -

Arlington Marsh

Arlington Marsh Harbor Estuary Program Restoration Site: Site: Arlington Marsh Watershed: Arthur Kill, NY Protection Status: Restorations ongoing and completed at Saw Mill Creek, Old Place Marsh, Gulfport Marsh, Mariner's Marsh, Chelsea Road Bridge, and Wilpon Pond Acreage: No data Project Summary: Salt Marsh Restoration/Non-Point Source Reduction Contact: Michael Feller, NYC Parks/NRG Contact Phone: (212) 360-1424 Website: www.nycgovparks.org/sub_about/parks_divisions/nrg/nrg_home.html HEP Website: www.harborestuary.org Email Corrections or Updates to [email protected] Source: NY/NJ Harbor Estuary Program, 2003 Arlington Marsh (Adapted from “An islanded Nature: Natural Area Conservation and Restoration in Western Staten Island, including the Harbor Herons Region” by Peter P. Blanchard III and Paul Kerlinger, published by The Trust for Public Land and the NYC Audubon Society.) Size, ecological importance, restoration potential, contiguity with existing parkland, and a high degree of development threat are all characteristics that place Arlington Marsh at the highest level of priority for conservation. Arlington Marsh is the largest remaining, intact salt marsh on the Kill van Kull in Staten Island. Despite development at its southern boundary, a DOT facility on the landward end of its eastern peninsula, and a marina on its eastern flank, Arlington Marsh provides more habitat, and in greater variety, for flora and fauna than it might initially appear. Arlington Marsh’s importance within the fabric of remaining open space in northwestern and western Staten Island continues to be recognized. In Significant Habitats and Habitat Complexes of the New York Bright Watershed (1998), the U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service identified Arlington Marsh as “one of the main foraging areas for birds of the Harbor Herons complex.” In September 1999, the site was recommended as a high priority of acquisition by the NY/NJ HEP Acquisition and Restoration Sub workgroup. -

What Is the Natural Areas Initiative?

NaturalNatural AAreasreas InitiativeInitiative What are Natural Areas? With over 8 million people and 1.8 million cars in monarch butterflies. They reside in New York City’s residence, New York City is the ultimate urban environ- 12,000 acres of natural areas that include estuaries, ment. But the city is alive with life of all kinds, including forests, ponds, and other habitats. hundreds of species of flora and fauna, and not just in Despite human-made alterations, natural areas are spaces window boxes and pet stores. The city’s five boroughs pro- that retain some degree of wild nature, native ecosystems vide habitat to over 350 species of birds and 170 species and ecosystem processes.1 While providing habitat for native of fish, not to mention countless other plants and animals, plants and animals, natural areas afford a glimpse into the including seabeach amaranth, persimmons, horseshoe city’s past, some providing us with a window to what the crabs, red-tailed hawks, painted turtles, and land looked like before the built environment existed. What is the Natural Areas Initiative? The Natural Areas Initiative (NAI) works towards the (NY4P), the NAI promotes cooperation among non- protection and effective management of New York City’s profit groups, communities, and government agencies natural areas. A joint program of New York City to protect natural areas and raise public awareness about Audubon (NYC Audubon) and New Yorkers for Parks the values of these open spaces. Why are Natural Areas important? In the five boroughs, natural areas serve as important Additionally, according to the City Department of ecosystems, supporting a rich variety of plants and Health, NYC children are almost three times as likely to wildlife. -

16 BRIAN JARVIS Thomas Pynchon Thomas Pynchon Is Perhaps Best

16 BRIAN JARVIS Thomas Pynchon Thomas Pynchon is perhaps best known for knowing a lot and not being known. His novels and the characters within them are typically engaged in the manic collection of information. Pynchon’s fiction is crammed with erudition on a vast range of subjects that includes history, science, technology, religion, the arts, and popular culture. Larry McMurtry recalls a legend that circulated in the sixties that Pynchon “read only the Encyclopaedia Britannica.”1 While Pynchon is renowned for the breadth and depth of his knowledge, he has performed a “calculated withdrawal” from the public sphere.2 He has never been interviewed. He has been photographed on only a handful of occasions (most recently in 1957). Inevitably, this reclusion has enhanced his cult status and prompted wild speculation (including the idea that Pynchon was actually J. D. Salinger). Reliable information about Pynchon practically disappears around the time his first novel was published in 1963. While Pynchon the author is a conspicuous absence in the literary marketplace, his fiction is a commanding presence. His first major work, V. (1963), has a contrapuntal structure in which two storylines gradually converge. The first line, set in New York in the 1950s, follows Benny Profane and a group of his bohemian acquaintances self-designated the “Whole Sick Crew.” The second line jumps between moments of historical crisis, from the Fashoda incident in 1898 to the Second World War and centers on Herbert Stencil’s quest for a mysterious figure known as “V.” Pynchon's second novel, The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), is arguably his most accessible work and has certainly been the most conspicuous on university syllabuses. -

View/Download Entire Issue Here

ISSN 1904-6022 www.otherness.dk/journal Otherness and the Urban Volume 7 · Number 1 · March 2019 Welcoming the interdisciplinary study of otherness and alterity, Otherness: Essays and Studies is an open-access, full-text, and peer-reviewed e-journal under the auspices of the Centre for Studies in Otherness. The journal publishes new scholarship primarily within the humanities and social sciences. ISSUE EDITOR Dr. Maria Beville Coordinator, Centre for Studies in Otherness GENERAL EDITOR Dr. Matthias Stephan Aarhus University, Denmark ASSOCIATE EDITORS Dr. Maria Beville Coordinator, Centre for Studies in Otherness Susan Yi Sencindiver, PhD Aarhus University, Denmark © 2019 Otherness: Essays and Studies ISSN 1904-6022 Further information: www.otherness.dk/journal/ Otherness: Essays and Studies is an open-access, non-profit journal. All work associated with the journal by its editors, editorial assistants, editorial board, and referees is voluntary and without salary. The journal does not require any author fees nor payment for its publications. Volume 7 · Number 1 · March 2019 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Maria Beville 1 ‘Some people have a ghost town, we have a ghost city’: 9 Gothic, the Other, and the American Nightmare in Lauren Beukes’s Broken Monsters Carys Crossen 2 Sanctuary City: 27 Pynchon’s Subjunctive New York in Bleeding Edge Inger H. Dalsgaard 3 Anthony Bourdain’s Cosmopolitan Table: 47 Mapping the ethni(C)ity through street food and television Shelby E. Ward 4 Eyeing Fear and Anxiety: 71 Postcolonial Modernity and Cultural Identity -

Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative

Overwhelmed and Underworked: Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative Miles Taylor A Thesis in The Department of Film Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada May 2020 © Miles Taylor 2020 Signature Page This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Miles Taylor Entitled: Overwhelmed and Underworked: Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative And submitted in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) Complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: Examiner Luca Caminati Examiner Mary Esteve Supervisor Martin Lefebvre Approved by Marc Steinberg 2020 Rebecca Duclos Taylor iii Abstract Overwhelmed and Underworked: Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative Miles Taylor This thesis proposes an artistic mode called aproductivity, which arises with the secular crisis of capitalism in the early 1970’s. It reads aproductivity as the aesthetic reification of Theodor Adorno’s negative dialectics, a peculiar form of philosophy that refuses to move forward, instead producing dialectics without synthesis. The first chapter examines the economic history aproductivity grows out of, as well as its relation to Francis Fukuyama’s concept of “The End of History.” After doing so, the chapter explores negative dialectics and aproductivity in relation to Adam Phillips’ concept of the transformational object. In the second chapter, the thesis looks at the Thomas Pynchon novel Inherent Vice (2009), as well as the 2014 Paul Thomas Anderson adaptation of the same name. -

Music in Thomas Pynchon's Mason & Dixon

ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): John Joseph Hess Affiliation(s): Independent Researcher Title: Music in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon Date: 2014 Volume: 2 Issue: 2 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/75 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/orbit.v2.2.75 Abstract: Through Pynchon-written songs, integration of Italian opera, instances of harmonic performance, dialogue with Plato’s Republic and Benjamin Franklin’s glass armonica performance, Mason & Dixon extends, elaborates, and investigates Pynchon’s own standard musical practices. Pynchon’s investigation of the domestic, political, and theoretical dimensions of musical harmony in colonial America provides the focus for the novel’s historical, political, and aesthetic critique. Extending Pynchon’s career-long engagement with musical forms and cultures to unique levels of philosophical abstraction, in Mason & Dixon’s consideration of the “inherent Vice” of harmony, Pynchon ultimately criticizes the tendency in his own fiction for characters and narrators to conceive of music in terms that rely on the tenuous and affective communal potentials of harmony. Music in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon John Joseph Hess Few readers of Thomas Pynchon would dispute William Vesterman’s claim that “poems and particularly songs, make up a characteristic part of Pynchon’s work: without them a reader’s experience would not be at 1 all the same.” While Vesterman was specifically interested in Pynchon’s poetic practice, Pynchon’s fifty year career as a novelist involves a sustained engagement with a range of musical effects. Music is a formal feature with thematic significance in Pynchon’s early short fiction and in every novel from V. -

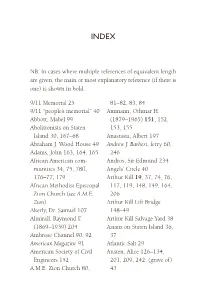

In Cases Where Multiple References of Equivalent Length Are Given, the Main Or Most Explanatory Reference (If There Is One) Is Shown in Bold

index NB: In cases where multiple references of equivalent length are given, the main or most explanatory reference (if there is one) is shown in bold. 9/11 Memorial 25 81–82, 83, 84 9/11 “people’s memorial” 40 Ammann, Othmar H. Abbott, Mabel 99 (1879–1965) 151, 152, Abolitionists on Staten 153, 155 Island 30, 167–68 Anastasia, Albert 197 Abraham J. Wood House 49 Andrew J. Barberi, ferry 60, Adams, John 163, 164, 165 246 African American com- Andros, Sir Edmund 234 munities 34, 75, 78ff, Angels’ Circle 40 176–77, 179 Arthur Kill 19, 37, 74, 76, African Methodist Episcopal 117, 119, 148, 149, 164, Zion Church (see A.M.E. 206 Zion) Arthur Kill Lift Bridge Akerly, Dr. Samuel 107 148–49 Almirall, Raymond F. Arthur Kill Salvage Yard 38 (1869–1939) 204 Asians on Staten Island 36, Ambrose Channel 90, 92 37 American Magazine 91 Atlantic Salt 29 American Society of Civil Austen, Alice 126–134, Engineers 152 201, 209, 242; (grave of) A.M.E. Zion Church 80, 43 248 index Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing- Boy Scouts 112 Room Companion 76 Breweries 34, 41, 243 Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Bridges: 149, 153 Arthur Kill Lift 148–49 Barnes, William 66 Bayonne 151–52, 242 Battery Duane 170 Goethals 150, 241 Battery Weed 169, 170, Outerbridge Crossing 150, 171–72, 173, 245 241 Bayles, Richard M. 168 Verrazano-Narrows 112, Bayley-Seton Hospital 34 152–55, 215, 244 Bayley, Dr. Richard 35, 48, Brinley, C. Coapes 133 140 British (early settlers) 159, Bayonne Bridge 151–52, 176; (in Revolutionary 242 War) 48, 111, 162ff, 235 Beil, Carlton B. -

Arthur Kill Wader Colonies

NYC Audubon Harbor Herons Program 31st Annual Survey Wading Bird, Cormorant, and Gull Nesting Activity in 2015 Tod Winston1, Susan Elbin1, and Elizabeth Craig1,2 1) NYC Audubon & 2) Cornell University Harbor Herons Annual Subcommittee Meeting: Greater NY/NJ Harbor Colonial Waterbirds Working Group December 3, 2015 Acknowledgements Study PI: Susan Elbin Our past survey leader: Liz Craig Numerous collaborators and volunteers: • Fieldwork! Annie Barry, John Burke, Liz Craig, Marisa Dedominicis, Melanie Del Rosario, Greg Elbin, Mike Feller, Laura Francoeur, Stefan Guelly, Tom Heinimann, Sarah Heintz, Jeff Kolodzinski, Debra Kriensky, Dave Künstler, Andrew Maas, Melissa Malloy, Ritamary McMahon, Melissa Murgittroyd, Ellen Pehek, Don Riepe, Erica Santana, Susan Stanley, Alex Summers • Permits and administration! George Frame, Dave Taft, Kathy Garofalo, Ellen Pehek, Hanem Abouelezz, Susan Stanley, Marit Larson, Joe Pane • NYC Parks and Recreation • National Park Service • NJ Audubon • Huckleberry Indians • American Littoral Society/Jamaica Bay Guardian Survey Area May 18-29, 2015 Wading birds of the NY/NJ Harbor Islands 10 species of long-legged waders: 7 observed in 2015 Great Blue Heron, Area herodias Great Egret, Ardea alba Snowy Egret, Egretta thula Little Blue Heron, Egretta caerulea Tricolored Heron, Egretta tricolor Cattle Egret, Bubulcus ibis Green Heron, Butorides virescens Black-Crowned Night-Heron, Nycticorax nycticorax Yellow-Crowned Night-Heron, Nyctanassa violacea Glossy Ibis, Plegadis falcinellus Other Nesting Species Colonial