Lexi Jennifer Weiner.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download YAM011

yetanothermagazine filmtvmusic aug2010 lima film festival 2010 highlights blockbuster season from around the world in this yam we review // aftershocks, inception, toy story 3, the ghost writer, taeyang, se7en, boa, shinee, bibi zhou, jing chang, the derek trucks band, time of eve and more // yam exclusive interview with songwriter diane warren film We keep working on that, but there’s toy story 3 pg4 the ghost writer pg5 so much territory to cover, and so You know the address: aftershocks pg6 very little of us. This is why we need [email protected] inception pg7 lima film festival// yam contributors. We know our highlights pg9 readers are primarily located in the amywong // cover// US, but I’m hoping to get people yam exclusive from other countries to review their p.s.: I actually spoke to Diane interview with diane warren pg12 local releases. The more the merrier, Warren. She's like the soundtrack music people. of our lives, to anyone of my the derek trucks band - roadsongs pg16 generation anyway. Check it out. se7en - digital bounce pg16 shinee - lucifer pg17 Yup, we’re grovelling for taeyang - solar pg17 contributors. I’m particularly eminem - recovery pg18 macy gray - the sellout pg18 interested in someone who is jing chang - the opposite me pg18 located in New York, since we’ve bibi zhou - i.fish.light.mirror pg18 nick chou - first album pg19 received a couple of screening boa - hurricane venus pg19 invites, but we got no one there. tv Interested? Hit me up. bad guy pg20 time of eve pg20 books uso. -

Twitterbrainz What Music Do People Share on Twitter?

TwitterBrainz what music do people share on Twitter? February 15, 2015 Open Data Project Research and Innovation Quim Llimona Àngel Farguell Modelling for Science and Engineering Abstract In this report we present TwitterBrainz, an interactive, real-time visualization of what songs are people posting on Twitter. Our system uses the MusicBrainz and Acous- ticBrainz APIs to identify the songs and extract acoustic metadata from them, which is displayed along with metadata from the tweet itself using a scatterplot metaphor for easy exploration. Clicking one of the dots/tweets/songs plays it back using the Tomahawk API, which can be used for reinventing our app into a music discovery tool. Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Previous similar works . 2 2 Development 3 2.1 Sources . 3 2.2 Pre-processing . 4 2.3 Visualization . 6 3 Product 6 3.1 Functionality . 6 3.2 Limitations . 8 3.3 Example uses . 9 4 Future improvements 11 1 1 Introduction The aim of this project is to build a web-based interactive visualization using Open Data tools. Since we are both musicians, we thought it had to be about visualizing music, in any of its forms. We knew about the AcousticBrainz API, which provides acoustic information about commercial songs, and found in Twitter a great opportunity for integration. The original idea was to find tweets from users that referenced the user was listening to a particular song, find metadata about that song, and then plot the metadata along with features extracted from the tweet itself, looking for correlations. For instance, one could expect that in work days people listen to more relaxed music than during the weekend. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Beets Documentation Release 1.5.1

beets Documentation Release 1.5.1 Adrian Sampson Oct 01, 2021 Contents 1 Contents 3 1.1 Guides..................................................3 1.2 Reference................................................. 14 1.3 Plugins.................................................. 44 1.4 FAQ.................................................... 120 1.5 Contributing............................................... 125 1.6 For Developers.............................................. 130 1.7 Changelog................................................ 145 Index 213 i ii beets Documentation, Release 1.5.1 Welcome to the documentation for beets, the media library management system for obsessive music geeks. If you’re new to beets, begin with the Getting Started guide. That guide walks you through installing beets, setting it up how you like it, and starting to build your music library. Then you can get a more detailed look at beets’ features in the Command-Line Interface and Configuration references. You might also be interested in exploring the plugins. If you still need help, your can drop by the #beets IRC channel on Libera.Chat, drop by the discussion board, send email to the mailing list, or file a bug in the issue tracker. Please let us know where you think this documentation can be improved. Contents 1 beets Documentation, Release 1.5.1 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Contents 1.1 Guides This section contains a couple of walkthroughs that will help you get familiar with beets. If you’re new to beets, you’ll want to begin with the Getting Started guide. 1.1.1 Getting Started Welcome to beets! This guide will help you begin using it to make your music collection better. Installing You will need Python. Beets works on Python 3.6 or later. • macOS 11 (Big Sur) includes Python 3.8 out of the box. -

Beets Documentation Release 1.3.3

beets Documentation Release 1.3.3 Adrian Sampson February 27, 2014 Contents i ii beets Documentation, Release 1.3.3 Welcome to the documentation for beets, the media library management system for obsessive-compulsive music geeks. If you’re new to beets, begin with the Getting Started guide. That guide walks you through installing beets, setting it up how you like it, and starting to build your music library. Then you can get a more detailed look at beets’ features in the Command-Line Interface and Configuration references. You might also be interested in exploring the plugins. If you still need help, your can drop by the #beets IRC channel on Freenode, send email to the mailing list, or file a bug in the issue tracker. Please let us know where you think this documentation can be improved. Contents 1 beets Documentation, Release 1.3.3 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Contents 1.1 Guides This section contains a couple of walkthroughs that will help you get familiar with beets. If you’re new to beets, you’ll want to begin with the Getting Started guide. 1.1.1 Getting Started Welcome to beets! This guide will help you begin using it to make your music collection better. Installing You will need Python. (Beets is written for Python 2.7, but it works with 2.6 as well. Python 3.x is not yet supported.) • Mac OS X v10.7 (Lion) and 10.8 (Mountain Lion) include Python 2.7 out of the box; Snow Leopard ships with Python 2.6. -

NOWHERE BOY UK/Canada 2009 98 Minutes

BRITISH SCHOOLS FILM FESTIVAL #5 NOWHERE BOY UK/Canada 2009 98 minutes Director Sam Taylor-Wood Cast John - Aaron Johnson Mimi - Kristin Scott Thomas Uncle George - David Threlfall Julia - Anne-Marie Duff Bobby - David Morrissey Paul - Thomas Brodie Sangster George - Sam Bell Selected Music Wild One performed by Jerry Lee Lewis Mr. Sandman performed by Dickie Valentine Shake, Rattle and Roll performed by Elvis Presley Rockin’ Daddy performed by Eddie Bond and The Stompers Hard Headed Woman performed by Wanda Jackson Hound Dog performed by Big Mama Thornton Hello Little Girl (song by John Lennon and Paul McCartney) performed by The Nowhere Boys Mother performed by John Lennon FSK: 12, recommended age: 14+ English with German subtitles Study Guide by Julian Name, 2010 Themes society, youth culture, coming of age, parents, music Questions for the class are organized in two categories: before viewing (bv) and after viewing (av). A work sheet with planned activities is also attached. Synopsis Directed by Sam Taylor-Wood, Nowhere Boy is a film about the life and growing up pains of a rather young rebellious dreamer called John Lennon. Set in Liverpool, the film begins in the mid-1950s, when John is a brash 15 year old schoolboy, always getting into trouble. The film ends two years later with him going to Hamburg, accompanied by his newly-formed band, The Beatles (interestingly, not mentioned in the film). Within these two years, John goes through a remarkable change. A change shaped largely by the two most important people in John’s life: both, women of extraordinary strength. -

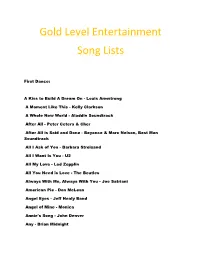

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists First Dance: A Kiss to Build A Dream On - Louis Armstrong A Moment Like This - Kelly Clarkson A Whole New World - Aladdin Soundtrack After All - Peter Cetera & Cher After All is Said and Done - Beyonce & Marc Nelson, Best Man Soundtrack All I Ask of You - Barbara Streisand All I Want Is You - U2 All My Love - Led Zepplin All You Need is Love - The Beatles Always With Me, Always With You - Joe Satriani American Pie - Don McLean Angel Eyes - Jeff Healy Band Angel of Mine - Monica Annie's Song - John Denver Any - Brian Midnight As Long as I'm Rocking With You - John Conlee At Last - Celine Dion At Last - Etta James At My Most Beautiful - R.E.M. At Your Best - Aaliyah Battle Hymn of Love - Kathy Mattea Beautiful - Gordon Lightfoot Beautiful As U - All 4 One Beautiful Day - U2 Because I Love You - Stevie B Because You Loved me - Celine Dion Believe - Lenny Kravitz Best Day - George Strait Best In Me - Blue Better Days Ahead - Norman Brown Bitter Sweet Symphony - Verve Blackbird - The Beatles Breathe - Faith Hill Brown Eyes - Destiny's Child But I Do Love You - Leann Rimes Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle By My Side - Ben Harper By Your Side - Sade Can You Feel the Love - Elton John Can't Get Enough of Your Love, Babe - Barry White Can't Help Falling in Love - Elvis Presley Can't Stop Loving You - Phil Collins Can't Take My Eyes Off of You - Frankie Valli Chapel of Love - Dixie Cups China Roses - Enya Close Your Eyes Forever - Ozzy Osbourne & Lita Ford Closer - Better than Ezra Color My World - Chicago Colour -

Disk Catalog by Category

DVD Karaoke 1-800-386-5743 KaraokeStar.com DVD DVD DVD DVD Why I Love You So Much Monica Lo Dijo El Corazon Sebastian, Joan Abrazame Fernandez, Alejandro Vocal Guides: Yes BOD0001 Lyric Sheet: No Can't Help Falling In Love Presley, Elvis Hasta Que Amanezca Sebastian, Joan Jamas Te Vi Tan Linda Fernandez, Alejandro I Will Beatles Julian Sebastian, Joan Madie Simplemente Nadie Fernandez, Alejandro Band On A Disc KaraokeStar.com Elvis Presley Lucky One Grant, Amy Amor De Luna Fernandez, Alejandro $19.99 Vocal Guides: No Love Is A Wonderful Thing Bolton, Michael DOK8502 Lyric Sheet: No Quiereme Fernandez, Alejandro CC Rider Presley, Elvis Emotion Bee Gees La Mitad Que Me Faltaba Fernandez, Alejandro Canta Combo DVD KaraokeStar.com Devil In Disguise Presley, Elvis Last Christmas Wham Que Seas Muy Feliz Fernandez, Alejandro Juan Gabriel $22.99 Don't Be Cruel Presley, Elvis Dust In The Wind Kansas Don't Presley, Elvis I Finally Found Someone Streisand, Barbra Amor Eterno Gabriel, Juan Vocal Guides: No DOK8507 Lyric Sheet: No Hawaiian Wedding Song Presley, Elvis Where Do You Go No Mercy Hjasta Que Te Conoci Gabriel, Juan Canta Combo DVD KaraokeStar.com I Wan You I Need You I Love Yo Presley, Elvis Real Thing Unknown Si Quieres Gabriel, Juan Super Hits Vol 1 $22.99 Lawdy Miss Clawdy Presley, Elvis Crazy Dream Unknown Cosas De Enamorados Gabriel, Juan Long Tall Sally Presley, Elvis When You Say Nothing At All Krauss, Alison La Farsante Gabriel, Juan Asereje Las Ketchup Mean Woman Blues Presley, Elvis In The Summertime Mungo, Jerry Debo Hacerlo -

Release V2.5.6

MusicBrainz Picard Release v2.5.6 Feb 16, 2021 MusicBrainz Picard User Guide by Bob Swift is licensed under CC0 1.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Picard Can. ...........................................2 1.2 Picard Cannot. .........................................2 1.3 Limitations...........................................2 2 Contributing to the Project3 3 Acknowledgements4 3.1 Editor and English Language Lead..............................4 3.2 Translation Teams.......................................4 3.3 Contributors..........................................4 4 Glossary of Terms 6 5 Getting Started 10 5.1 Download & Install Picard................................... 10 5.2 Main Screen.......................................... 12 5.3 Status Icons........................................... 18 6 Configuration 20 6.1 Screen Setup.......................................... 20 6.2 Action Options......................................... 21 6.3 Option Settings......................................... 21 7 Tags & Variables 66 7.1 Basic Tags........................................... 66 7.2 Advanced Tags......................................... 70 7.3 Basic Variables......................................... 72 7.4 File Variables.......................................... 73 7.5 Advanced Variables...................................... 74 7.6 Classical Music Tags...................................... 75 7.7 Tags from Plugins...................................... -

Big Shots 1X01 - Pilot.Pdf

ACT ONE 1 EXT. FIRMWOOD COUNTRY CLUB - DAY 1 We PUSH up the driveway, along the tennis court and swimming pool, and into the barbecue, past the perfectly-manicured grounds and the monied MEMBERS and GUESTS mingling on the patio under a banner that reads -- “ANNUAL LABOR DAY BARBECUE.” This is Firmwood, an exclusive country club located amongst the monied estates of Westchester, New York, just north of New York City, where many of our most successful CEOS -- and CEOs to-be -- live, work and play. Amidst the snippets of dialogue -- “No, the insider trading charges were dropped,” “She was a wonderful nanny until she was deported,” “I have the X3 and the X5. One day I hope to get the X7.” -- we HEAR something slightly more interesting -- the SOUNDS of SEX. And we’re -- 2 INT. WINE CELLAR - FIRMWOOD - CONTINUOUS 2 A COUPLE is engaged in passionate love-making. DUNCAN, early 40s and dapper, has LISBETH, also early 40s and classically attractive -- pinned amidst the aging wine bottles. LISBETH Do you think they’re going to hear us? DUNCAN Only if we keep doing it right... Another beat of lovemaking. We’re not quite sure who this pair of lovers is until... LISBETH Oh...I forgot to mention -- you need to talk to Cameron. She dropped out of school last week. Duncan looks at her. Lisbeth nods. But he stays focused on the task at hand. And Lisbeth seems to be enjoying it too. LISBETH (CONT’D) God. If we did it like this when we were married, we might still be married. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Verses from Jordan a Play About Chasing

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-15-2009 Verses from Jordan A Play About Chasing Bradley Troll University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Troll, Bradley, "Verses from Jordan A Play About Chasing" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 932. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/932 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Verses from Jordan A Play About Chasing A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts In English Creative Writing, Playwriting by Bradley Troll B.S. McNeese State University, 2001 M.A. McNeese State University, 2006 May, 2009 - Characters - *Four actors play all the roles: The actor playing JORDAN. The actor playing JAKE as well as JORDAN’S DOUBLE and various characters behind the scrim.