1 Technology and Femininity in Marcel L'herbier's L'inhumaine Katherine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mezzo-Soprano Onstage and Offstage: a Cultural History of the Voice-Type, Singers and Roles in the French Third Republic (1870–1918)

The mezzo-soprano onstage and offstage: a cultural history of the voice-type, singers and roles in the French Third Republic (1870–1918) Emma Higgins Dissertation submitted to Maynooth University in fulfilment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Maynooth University Music Department October 2015 Head of Department: Professor Christopher Morris Supervisor: Dr Laura Watson 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page number SUMMARY 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 LIST OF FIGURES 5 LIST OF TABLES 5 INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER ONE: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO AS A THIRD- 19 REPUBLIC PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN 1.1: Techniques and training 19 1.2: Professional life in the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique 59 CHAPTER TWO: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO ROLE AND ITS 99 RELATIONSHIP WITH THIRD-REPUBLIC SOCIETY 2.1: Bizet’s Carmen and Third-Republic mores 102 2.2: Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila, exoticism, Catholicism and patriotism 132 2.3: Massenet’s Werther, infidelity and maternity 160 CHAPTER THREE: THE MEZZO-SOPRANO AS MUSE 188 3.1: Introduction: the muse/musician concept 188 3.2: Célestine Galli-Marié and Georges Bizet 194 3.3: Marie Delna and Benjamin Godard 221 3.3.1: La Vivandière’s conception and premieres: 1893–95 221 3.3.2: La Vivandière in peace and war: 1895–2013 240 3.4: Lucy Arbell and Jules Massenet 252 3.4.1: Arbell the self-constructed Muse 252 3.4.2: Le procès de Mlle Lucy Arbell – the fight for Cléopâtre and Amadis 268 CONCLUSION 280 BIBLIOGRAPHY 287 APPENDICES 305 2 SUMMARY This dissertation discusses the mezzo-soprano singer and her repertoire in the Parisian Opéra and Opéra-Comique companies between 1870 and 1918. -

Georgette Leblanc

UNE MUSE DE MAETERLINCK GEORGETTE LEBLANC Evoquer un Maurice Maeterlinck, familier, intime, est entre• prise malaisée : une telle gloire a besoin d'infiniment de respect. Certaine vérité conserve ses droits. Enfant, puis adolescent, j'ai bien connu Maurice Maeterlinck, soit chez mon père Lucien Descaves, soit chez mon oncle le Dr Crépel, qui fut l'un des premiers à préconiser et à utiliser les traitements à l'électricité, et qui comptait dans sa clientèle les plus hautes personnalités du monde de la Politique, des Arts et des Lettres : de Briand à Clemenceau, de Tristan Bernard à Pierre Loti, de Gémier à Claude Debussy. Les relations entre Lucien Descaves et Maurice Maeterlinck dataient du Théâtre Libre, au lendemain du fameux article d'Octave Mirbeau, paru dans le Figaro du 24 août 1890 : « M. Maurice Maeterlinck nous a donné l'œuvre la plus géniale et la plus naïve aussi, comparable et — oserai-je le dire ? — supé• rieure en beauté à ce qu'il y a de plus beau dans Shakespeare. Cette œuvre s'appelle La Princesse Maleine. Existe-t-il dans le monde vingt personnes qui la connaissent ? » C'était alors, un solide garçon de vingt-huit ans, de belle carrure, fier de ses biceps, de ses exploits sportifs : cyclisme, boxe, natation et dont les tenues, un peu voyantes, étonnaient la galerie : panta• lons bouffants, chemises chamarées ; et fier, à l'époque, d'une mous• tache — à la gauloise — attribut conquérant qu'il fit rapidement disparaître. Il s'assagit également dans l'ordre de ses recherches vestimentaires. Quand je le vis, pour la première fois, aux environs de mes 214 UNE MUSE DE MAETERLINCK huit ans, dans le pavillon paternel de la rue de la Santé, il arrivait paré de tous les prestiges ; c'était « Monsieur — le — Poète » qu'avait lancé Mirbeau. -

'L'isle Joyeuse'

Climax as Orgasm: On Debussy’s ‘L’isle Joyeuse’ Esteban Buch To cite this version: Esteban Buch. Climax as Orgasm: On Debussy’s ‘L’isle Joyeuse’. Music and Letters, Oxford Univer- sity Press (OUP), 2019, 100 (1), pp.24-60. 10.1093/ml/gcz001. hal-02954014 HAL Id: hal-02954014 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02954014 Submitted on 30 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Esteban Buch, ‘Climax as Orgasm: On Debussy’s “L’isle Joyeuse”’, Music and Letters 100/1 (February 2019), p. 24-60. Climax as Orgasm: On Debussy’s L’isle joyeuse This article discusses the relationship of musical climax and orgasm by considering the case of L’isle joyeuse, a piano piece that Claude Debussy (1862-1918) began in 1903, completing it in the Summer of 1904 soon after starting a sentimental relationship with Emma Bardac, née Moyse (1862-1934), his second wife and the mother of his daughter Claude-Emma, alias ‘Chouchou’ (1905-1919). By exploring the genesis of the piece, I suggest that the creative process started as the pursuit of a solitary exotic male fantasy, culminating in Debussy’s sexual encounter with Emma and leading the composer to inscribe their shared experience in the final, revised form of the piece. -

Maeterlinck Et Robert Scheffer. À Propos D'un

Maeterlinck et Robert Scheffer. À propos d’un compte rendu du Chemin nuptial (1895) Fabrice van de Kerckhove Archives et Musée de la littérature Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique Méditant sur sa propre personne, sur le futur et l’absolu, M. Maeterlinck commença par opiner que le monde n’est que drame et ténèbres. Pour y voir clair il alluma une lanterne sourde; et dès lors ce fut devant ses yeux le plus étrange défilé d’êtres falots, s’agitant confusément dans la pénombre, se cherchant et ne se trouvant pas, se lamentant, petit peuple de farfadets élégiaques aspirant à la grande lumière en murmurant, qui sa complainte, qui sa chanson de nourrice, qui son frêle amour, tous leur angoisse. […] Conformément à la vision qu’il venait d’avoir, il agença des scènes de lanterne magique, suavement effroyables. Avec des gestes d’automates, les mêmes personnages peints sur papier huilé, @nalyses, vol. 7, nº 3, automne 2012 se disaient des choses, des choses... indicibles. Avant tout les intriguait ce qui peut bien se passer derrière une porte close; rien que de redoutable, évidemment. Ce pourquoi, ils allaient y voir, et, tels des rats pris au piège, expiraient, en grignotant des alexandrins blancs, de Bruxelles. D’ailleurs, ils avaient tous une infirmité, l’un était aveugle, l’autre sourd, le troisième boiteux, celui-là, vraiment déraisonnablement vieux; ce qui expliquait bien des catastrophes. Quant aux héroïnes, autant de blondes miss angéliquement pures, décalquées de Botticelli, et tombant dans la gueule du loup avec des froissements de robe neigeuse, des éparpillements de fleur d’oranger, et le cri suprême : « oh maman! » Elles avaient en général pour compagnon un petit mouton blanc qui bêlait des « lieder » de Gabriel Fabre. -

MUSIC and the ECLIPSE of MODERNISM By

SIGNAL TO NOISE: MUSIC AND THE ECLIPSE OF MODERNISM By MATTHEW FRIEDMAN A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of T.J. Jackson Lears and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Signal to Noise: Music and the Eclipse of Modernism By MATTHEW FRIEDMAN Dissertation Director: T.J. Jackson Lears There was danger in the modern American soundscape; the danger of interruption and disorder. The rhetoric of postwar aural culture was preoccupied with containing sounds and keeping them in their appropriate places. The management and domestication of noise was a critical political and social issue in the quarter century following the Second World War. It was also an aesthetic issue. Although technological noise was celebrated in modern American literature, music and popular culture as a signal of technological sublime and the promise of modern rationality in the US, after 1945 noise that had been exceptional and sublime became mundane. Technological noise was resignified as "pollution" and narrated as the aural detritus of modernity. Modern music reinforced this project through the production of hegemonic fields of representation that legitimized the discursive boundaries of modernity and delegitimized that which lay outside of them. Postwar American modernist composers, reconfigured as technical specialists, developed a hyper-rational idiom of "total control" which sought to discipline aural disorder and police the boundaries between aesthetically- acceptable music and sound and disruptive noise. -

Stony Brook Opera 2016-2017 Season

LONG ISLAND OPERA GUILD NEWSLETTER &$%( ! &$%'"&$%( Debussy’s original opera, the Recital Hall is ideally suited for an intimate chamber production of Impressions de Pelléas. The opera will be sung in the original French language, with projected titles in English. For our chamber opera production on Friday, This issue of our Newsletter is devoted entirely to February 24 in the Recital Impressions de Pelléas, and includes background articles Hall (with a repeat performance at the Second about Debussy’s original opera and Peter Brook’s 1992 Presbyterian Church in Manhattan on Saturday, Paris production of Impressions, a synopsis, and brief February 25), we are pleased to present Impressions de bios of our artists, with their photos. I am convinced that Pelléas, Peter Brook’s and Marius Constant’s brilliant this will be a wonderful evening in the theater. Tickets adaptation of Claude Debussy’s operatic masterpiece for the Stony Brook performance are available at the Pelléas et Mélisande. Impressions de Pelléas Staller Center Box Office for $10 each. (Impressions of Pelléas) is scored for a cast of six, two pianos, and percussion. Soprano Catherine Sandstedt and Finally, my sincere thanks to all of you who have made tenor Jeremy Little play the title roles of Mélisande and tax-deductible contributions to the Long Island Opera Pelléas, while baritone Alexander Hahn performs the Guild in support of our 2016-2017 season. If you have role of Golaud, mezzo soprano Kristin Starkey that of been meaning to make a contribution but have not yet Geneviève, and Elyse Saucier that of the child Yniold. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 43,1923-1924, Trip

SANDERS THEATRE • . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY Thursday Evening, December 6, at 8.00 %. S§V r's'i W ffM^p BOSTON SYMPHONY ORQ1ESTRK INC. FQRTY-THIRD SEASON I923-J924 PR5GRHAME 13 % M. STEINERT &. SONS New England Distributors for STEINWAY STEINERT JEWETT WOODBURY PIANOS Duo -ART Reproducing Pianos Pianola Pianos JIMITTflTflti VICTROLAS VICTOR RECORDS DeForest Radio Merchandise STEINERT HALL 162 Boylston Street IH)s]()N MASS. SANDERS THEATRE . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY FORTY-THIRD SEASON, 1923-1924 INC. PIERRE MONTEUX, Conductor SEASON 1923-1924 THURSDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 6, at 8.00 o'clock WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1923, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. FREDERICK P. CABOT President GALEN L. STONE ....:. Vice-President ERNEST B. DANE . Treasurer ALFRED L. AIKEN ARTHUR LYMAN FREDERICK P. CABOT HENRY B. SAWYER ERNEST B. DANE GALEN L. STONE M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE BENTLEY W. WARREN JOHN ELLERTON LODGE E. SOHIER WELCH W. H. BRENNAN, Manager G. E. JUDD, Assistant Manager l — '-BEETHOYt \ and c \itu/x ' Ar J\T : STEINWAY T/7£ INSTRUMENT OF THE IMMORTAL T the 26th of March, 1827, died Liszt and Rubinstein, for \X agncr, Ber ONLudwig van l'>cthovcn,of whom and Gounod. And today, a still grc it has been said that he was the Steinway than these great men kn« st of all musicians. A generation responds to the touch of Pa. lati-r was born the Stein way Piano, which Rachmaninoff and Hofmann. Such if ackno" tO be the greatest of all fact, are the fortunes ol time, that tod pianofortes. -

REHEARSAL and CONCERT

Boston Symphony Orchestra. SYMPHONY Hall, boston, HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES. (Telephone, 1492 Back Bay.) TWENTY-FIFTH SEASON, I905-J906. WILHELM GERICKE, CONDUCTOR. programme OF THE SIXTH REHEARSAL and CONCERT WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE. FRIDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER 24, AT 2.30 O'CLOCK. SATURDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 25, AT 8.00 O'CLOCK. Published by C. A. ELLIS, Maiuger. 381 HAROLD BAUER Who gives his first Boston Recital of this season in Jordan Hall on Monday Afternoon, November 27, writes as follows of the iiasini&3|araltn PIANO Messrs. Mason & Hamlin, Boston. Gentlemen : In a former letter to you I expressed my delight and satisfaction with your magnifi- cent pianofortes, and I have once more to thank you and to admire your untiring efforts to attain an artistic ideal. Your latest model, equipped with the centri(>etal tendon bars, has developed and intensified the qualities of its precursors and has surpassed my highest expectations. As you know, I have used these instruments under many different conditions, in recital, with orchestra, in small and in large halls, and their adaptability to all require- ments has equally astonished and delighted me. The tone is, as always, one of never- failing beauty, the action is wonderful in its delicacy and responsiveness, and I consider that, as an instrument for bringing into prominence the individual qualities of tone and touch of the player, the Mason & Hamlin piano stands absolutely pre-eminent. The vertical grand (style O) is the only instrument of its kind, as far as I am aware, capable of giving complete satisfaction lo any one accustomed to play upon a grand, and I have no hesitation in saying that it is without exception the finest upright piano I have ever met with. -

Au-Delà Du Film D'art. Sur Deux Films Retrouvés À La Cinémathèque De

1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze Revue de l'association française de recherche sur l'histoire du cinéma 56 | 2008 Le film d'Art & les films d'art en Europe (1908-1911) Au-delà du film d’art. Sur deux films retrouvés à la Cinémathèque de Toulouse Beyond film d’art. On two films rediscovered at the Cinémathèque de Toulouse Christophe Gauthier Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/1895/4083 DOI : 10.4000/1895.4083 ISBN : 978-2-8218-0990-1 ISSN : 1960-6176 Éditeur Association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma (AFRHC) Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 décembre 2008 Pagination : 337-334 ISBN : 978-2-913758-57-5 ISSN : 0769-0959 Référence électronique Christophe Gauthier, « Au-delà du film d’art. Sur deux films retrouvés à la Cinémathèque de Toulouse », 1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze [En ligne], 56 | 2008, mis en ligne le 01 décembre 2011, consulté le 23 septembre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/1895/4083 ; DOI : 10.4000/1895.4083 © AFRHC Au-delà du film d’art Sur deux films retrouvés à la Cinémathèque de Toulouse par Christophe Gauthier 1895 / n° 56 décembre 2008 Prologue Dans les années 1970, Raymond Borde fit entrer dans les collections de la Cinémathèque de 327 Toulouse un ensemble de films nitrate des années 1909-1915, issus entre autres des séries d’art produites par Pathé. On y recense notamment la Vengeance du sire de Guildo de Gérard Bourgeois (1909), Fouquet, l’homme au masque de fer de Camille de Morlhon (1910) ou encore le Siège de Calais d’Henri Andréani (1910). -

VOCAL 78 Rpm Discs Minimum Bid As Indicated Per Item

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs Minimum bid as indicated per item. Listings “Just about 1-2” should be considered as mint and “Cons. 2” with just slight marks. For collectors searching top copies, you’ve come to the right place! The further we get from the era of production (in many cases now 100 years or more), the more difficult it is to find such excellent extant pressings. Some are actually from mint dealer stocks and others the result of having improved copies via dozens of collections purchased over the past fifty years. * * * For those looking for the best sound via modern reproduction, those items marked “late” are usually of high quality shellac, pressed in the 1950-55 period. A number of items in this particular catalogue are excellent pressings from that era. Also featured are many “Z” shellac Victors, their best quality surface material (later 1930s) and PW (Pre-War) Victor, almost as good surface material as “Z”. Likewise laminated Columbia pressings (1923- 1940) offer particularly fine sound. * * * Please keep in mind that the minimum bids are in U.S. Dollars, a benefit to most collectors. * * * “Text label on verso.” For a brief period (1912-‘14), Victor pressed silver-on-black labels on the reverse sides of some of their single-faced recordings, usually featuring translations of the text or similarly related comments. VERTICALLY CUT RECORDS. There were basically two systems, the “needle-cut” method employed by Edison, which was also used by Aeolian-Vocalion and Lyric and the “sapphire ball” system of Pathé, also used by Rex. and vertical Okeh. -

Rehearsal and Concert

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON (S-MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES _, , . ( Ticket Office, 1492 J „ , Telephones ^^'^^ ^^^^^ J Administration Offices, 3200 } THIRTIETH SEASON, 1910 AND 1911 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor Programme nf % Nineteenth Rehearsal and Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE ^NOTES BYi^PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON, MARCH 17 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, MARCH 18 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK COPYRIGHT, 1910, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A.ELLIS, MANAGER WM. L. WHITNEY International School for Vocalists BOSTON NEW YORK SYMPHONY CHAMBERS 134 CARNEQIE HALL 246 HUNTINQTON AVE. CORNER OP S7th AND 7th AVE. PORTLAND HARTFORD Y. M. C. A. BUILDING HARTFORD SCHOOL OP MUSIC ' CONGRESS SQUARE 8 SPRING STREET Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL Thirtieth Season, 1910-1911 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor Violins. Witek, A., Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Ceneert-master. Kuntz, D. Krafft, F. W. Noack, S. jm.iuiiu<mm.m>M<^<^.M.<V

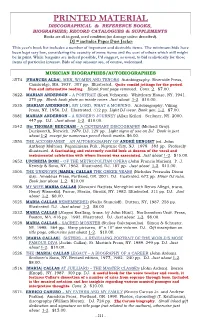

THE RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE Given Below Is the Featured Artist(S) of Each Issue (D=Discography, B=Biographical Information)

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, BIOGRAPHIES; RECORD CATALOGUES & SUPPLEMENTS Books are all in good, used condition (no damage unless described). DJ = includes Paper Dust Jacket This year’s book list includes a number of important and desirable items. The minimum bids have been kept very low, considering the scarcity of some items and the cost of others which still might be in print. While bargains are indeed possible, I’d suggest, as usual, to bid realistically for those items of particular interest. Bids of any amount are, of course, welcomed. MUSICIAN BIOGRAPHIES/AUTOBIOGRAPHIES 3574. [FRANCES ALDA]. MEN, WOMEN AND TENORS. Autobiography. Riverside Press, Cambridge, MA. 1937. 307 pp. Illustrated. Quite candid jottings for the period. Fun and informative reading. Blank front page removed. Cons. 2. $7.00. 3622. MARIAN ANDERSON – A PORTRAIT (Kosti Vehanen). Whittlesey House, NY. 1941. 270 pp. Blank book plate on inside cover. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3535. [MARIAN ANDERSON]. MY LORD, WHAT A MORNING. Autobiography. Viking Press, NY. 1956. DJ. Illustrated. 312 pp. Light DJ wear. Book gen. 1-2. $7.00. 3581. MARIAN ANDERSON – A SINGER’S JOURNEY (Allan Keiler). Scribner, NY. 2000. 447 pp. DJ. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3542. [Sir THOMAS] BEECHAM – A CENTENARY DISCOGRAPHY (Michael Gray). Duckworth, Norwich. 1979. DJ. 129 pp. Light signs of use on DJ. Book is just about 1-2 except for numerous pencil check marks. $6.00. 3550. THE ACCOMPANIST – AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ANDRÉ BENOIST (ed. John Anthony Maltese). Paganiniana Pub., Neptune City, NJ. 1978. 383 pp. Profusely illustrated. A fascinating and extremely candid look at dozens of the vocal and instrumental celebrities with whom Benoist was associated.