CAZA) Accreditation Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captive Orcas

Captive Orcas ‘Dying to Entertain You’ The Full Story A report for Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS) Chippenham, UK Produced by Vanessa Williams Contents Introduction Section 1 The showbiz orca Section 2 Life in the wild FINgerprinting techniques. Community living. Social behaviour. Intelligence. Communication. Orca studies in other parts of the world. Fact file. Latest news on northern/southern residents. Section 3 The world orca trade Capture sites and methods. Legislation. Holding areas [USA/Canada /Iceland/Japan]. Effects of capture upon remaining animals. Potential future capture sites. Transport from the wild. Transport from tank to tank. “Orca laundering”. Breeding loan. Special deals. Section 4 Life in the tank Standards and regulations for captive display [USA/Canada/UK/Japan]. Conditions in captivity: Pool size. Pool design and water quality. Feeding. Acoustics and ambient noise. Social composition and companionship. Solitary confinement. Health of captive orcas: Survival rates and longevity. Causes of death. Stress. Aggressive behaviour towards other orcas. Aggression towards trainers. Section 5 Marine park myths Education. Conservation. Captive breeding. Research. Section 6 The display industry makes a killing Marketing the image. Lobbying. Dubious bedfellows. Drive fisheries. Over-capturing. Section 7 The times they are a-changing The future of marine parks. Changing climate of public opinion. Ethics. Alternatives to display. Whale watching. Cetacean-free facilities. Future of current captives. Release programmes. Section 8 Conclusions and recommendations Appendix: Location of current captives, and details of wild-caught orcas References The information contained in this report is believed to be correct at the time of last publication: 30th April 2001. Some information is inevitably date-sensitive: please notify the author with any comments or updated information. -

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List – Updated July 1, 2021 The following AZA-accredited institutions have agreed to offer a 50% discount on admission to visiting Santa Barbara Zoo Members who present a current membership card and valid picture ID at the entrance. Please note: Each participating zoo or aquarium may treat membership categories, parking fees, guest privileges, and additional benefits differently. Reciprocation policies subject to change without notice. Please call to confirm before you visit. Iowa Rosamond Gifford Zoo at Burnet Park - Syracuse Alabama Blank Park Zoo - Des Moines Seneca Park Zoo – Rochester Birmingham Zoo - Birmingham National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium - Staten Island Zoo - Staten Island Alaska Dubuque Trevor Zoo - Millbrook Alaska SeaLife Center - Seaward Kansas Utica Zoo - Utica Arizona The David Traylor Zoo of Emporia - Emporia North Carolina Phoenix Zoo - Phoenix Hutchinson Zoo - Hutchinson Greensboro Science Center - Greensboro Reid Park Zoo - Tucson Lee Richardson Zoo - Garden Museum of Life and Science - Durham Sea Life Arizona Aquarium - Tempe City N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher - Kure Beach Arkansas Rolling Hills Zoo - Salina N.C. Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores - Atlantic Beach Little Rock Zoo - Little Rock Sedgwick County Zoo - Wichita N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island - Manteo California Sunset Zoo - Manhattan Topeka North Carolina Zoological Park - Asheboro Aquarium of the Bay - San Francisco Zoological Park - Topeka Western N.C. (WNC) Nature Center – Asheville Cabrillo Marine Aquarium -

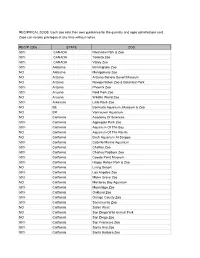

2006 Reciprocal List

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

Black-Footed Ferret Media

coming soon to Canada The black-footed ferret returns to the Canadian prairies The black-footed ferret is one of North America’s most endangered animals and just a few decades ago, was thought to be extinct. Now after several years of international effort, the black-footed ferret will be reintroduced into the wild in Canada in Fall 2009. In 2004, the Toronto Zoo, in partnership with Parks Canada, US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), Calgary Zoo, private stakeholders and other organizations established a joint Black-footed Ferret/Black-tailed Prairie Dog Canadian Recovery Team to look at the potential for reintroducing black-footed ferrets into Grasslands National Park (GNP) in Saskatchewan. After a lot of hard work on many levels, reintroduction of black-footed ferrets into black-footed ferret kits GNP is now planned for the fall of 2009. 4 spring 2009 collections back from near-extinction The black-footed ferret is the only native ferret known to North America and is listed as one of North America’s most endangered species. Ferrets prey almost exclusively on prairie dogs and inhabit prairie dog burrows. Loss of prairie dogs due to wide-scale extermination, agricultural conversion of their habitat, and epidemics of sylvatic plague (black plague) have resulted in the loss of about 95% of the ferret range since the 1800s. The black-footed ferret was thought to be extinct in the mid 1970s but in 1981 there was a dramatic discovery of a small population in Meetetse, Wyoming. Between 1985 and 1987, 18 ferrets were brought into captivity for the purpose of setting up a captive breeding and reintroduction program to save the species. -

State City Zoo Or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact

Updated March 25th, 2021 State City Zoo or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone # CANADA Calgary -Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Katie Frost 403-232-9386 Granby - Quebe Granby Zoo 50% Mireille Forand 450-372-9113 x2103 Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Membership Dept 416-392-9101 Winnipeg - ManiAssiniboine Park Zoo 50% Leah McDonald 204-927-6062 If the zoo or aquarium to which MEXICO León Parque Zoológico de León 50% David Rocha 52-477-210-2335 you belong has 50% in the Reciprocity column, you can Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Patty Pendleton 205-879-0409 x232 expect to receive a 50% discount Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% Shannon Wolf 907-224-6355 on admission at all the zoos and Arizona Phoenix Phoenix Zoo 50% Membership Dept 602-914-4393 aquariums on this list (except, of course, those that are FREE TO Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Membership Dept 877-526-3960 THE PUBLIC). Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Membership Dept 520-881-4753 ALWAYS CALL AHEAD* Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Kelli Enz 501-371-4589 If the zoo or aquarium to which California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 100% & 50% Becky Maxwell 805-461-5080 x2105 you belong has 100% and 50% Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 100% & 50% Kathleen Juliano 707-441-4263 in the Reciprocity column, you can expect to receive free Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Membership Office559-498-5921 admission to the zoos and Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Membership Dept 323-644-4759 aquariums that also have 100% Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Membership Dept 510-632-9525 x160 and 50% in the Reciprocity column and those that are FREE Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Elisa Escobar 760-346-5694 x2111 TO THE PUBLIC; and a 50% Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Membership Dept 916-808-5888 discount on admission to the San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Jaz Cariola 415-623-5310 zoos and aquariums that have 50% in the Reciprocity column. -

Killer Whale (Aka Orca) Orcinus Orca

PGAV Zoo Design SDT Animal of the Month Killer Whale (aka Orca) Orcinus orca 1. Animal Type: Mammal 2. Conservation Status: Endangered (Southern resident population only—Others: Status unknown) a. Range/Habitat i. From the open sea to coasts, from equator to polar areas. ii. The most distributed of all cetaceans, it occurs in all oceans and seas. 3. Size a. Male: 10 tons and 19’ long b. Female: 7.5 tons and 16’ long c. At birth: 6 ½ feet to 8 feet 4. Social Structure a. Killer whales are a social species living in pods of 3-25 b. Killer whales use their calls to coordinate hunting behavior and to maintain contact with other members of their pod. Clicks are used by all toothed whales for echolocation, and they may also be used to communicate. i. With orcas, several resident pods may join to form a community. Each pod has a unique dialect, similar to other pods in its community. It is quite different from the dialects of other pods with which they are not in contact. ii. Studies of the orca show the subtlety and variety of whale language. They use discrete calls – distinct sounds separated into characteristic types that can be heard 5 miles away. Those in the northwest use between 7-17 calls each. They make different noises when playing or socializing. 5. Reproduction a. Gestation period is thought to be 12-16 months, with most calves born between October and March. b. Orcas have long childhoods, reaching maturity about 15 years old. c. A female can produce as many as 5 calves over a 25 year period. -

While Rome Burns…A Report Into Conditions in the Zoos of Ontario

While Rome Burns … A Report into Conditions in the Zoos of Ontario Prepared by: Samantha Lindley, BVSc, MRCVS September 1998 Published by: Zoocheck Canada Inc. 2646 St. Clair Avenue East Toronto, Ontario M4B 3M1 (Canada) Ph (416) 285-1744 Fax (416) 285-4670 Email: [email protected] Web Site: www.zoocheck.com World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA) Canada 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Ste. 960 Toronto, Ontario M4P 1Y3(Canada) Ph (416) 369-0044 Fax (416) 369-0147 Email: [email protected] Web Site: www.wspa.ca While Rome Burns…A Report into Conditions in the Zoos of Ontario Table of Contents Foreword …………………………………………………………………………. i About the Author ………………………………………………………………… iii While Rome Burns . Introduction ……………………..……..……………….. 1 Zoos in Ontario: A Discussion ………………………………………………….. 3 The “Ideal” Zoo? ………………………………………………………………… 3 Get-aways ……………………………………………………………………….. 3 Safety and Security ……………………………………………………………… 3 Education ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Behaviour ………………………………………………………………………… 5 Stereotypic Behaviour ……………………………………………………………. 5 Stereotypic Behaviour vs. Displacement Behaviour …………………………….. 6 The Conservation Argument …………………………………………………….. 7 The Welfare Issue ……………………………………………………………….. 8 Zoos in Ontario Bergeron’s Exotic Animal Sanctuary …………………………………………… 11 Greenview Aviaries, Park and Zoo ……………………………………………… 15 The Killman Zoo ………………………………………………………………… 19 Lazy Acre Farm …………………………………………………………………. 25 Marineland of Canada …………………………………………………………… 29 Northwoods Buffalo and Exotic Animal Ranch ………………………………… 35 Pineridge -

Stopping the Use, Sale and Trade of Whales and Dolphins in Canada How Protection Is Consistent with WTO Obligations

Stopping the use, sale and trade of whales and dolphins in Canada How protection is consistent with WTO obligations Prepared by Leesteffy Jenkins, Attorney at Law 219 West Main St., P.O. Box 634 Hillsborough, NH 03244-0634 Phone (603) 464-4395 For ZOOCHECK CANADA INC. 3266 Yonge Street, Suite 1417 Toronto, Ontario M4N 3P6 (416) 285-1744 (p) (416) 285-4670 (f ) [email protected] www.zoocheck.com This legal analysis was commissioned by Zoocheck Canada as part of a research initiative looking into how trade laws impact the trade and use of whales and dolphins in Canada, and to educate the public about the same. Page 1 April 25, 2003 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether a Canadian ban on the import and export of live cetaceans, wild-caught, captive born or those caught earlier in the wild and now considered captive, would violate Canada's obligations pursuant to the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreements. CONCLUSION It is my understanding that there is currently no specific Canadian legislation banning the import/export of live cetaceans. Based on the facts* presented to me, however, it is my opinion that such legislation could be enacted consistent with WTO rules. This memorandum attempts to outline both the conditions under which Canadian regulation of trade in live cetaceans may be consistent with the WTO Agreements, as well as provide some guidance in the crafting of future legislation. PEER REVIEW & COMMENTS Chris Wold, Steve Shrybman, Esq Clinical Professor of Law and Director Sack, Goldblatt, Mitchell International Environmental Law Project 20 Dundas Street West, Ste 1130 Northwestern School of Law Toronto, Ontario M5G 2G8 Lewis and Clark College Tel.: (416) 979-2235 10015 SW Terwilliger Blvd Email: [email protected] Portland, Oregon, U.S.A. -

Recommendations for the Care and Maintenance of Marine Mammals © Canadian Council on Animal Care, 2014

Recommendations for the care and maintenance of marine mammals © Canadian Council on Animal Care, 2014 ISBN: 978-0-919087-57-6 Canadian Council on Animal Care 190 O’Connor St., Suite 800 Ottawa ON K2P 2R3 http://www.ccac.ca Acknowledgements The development of the Recommendations for the care and maintenance of marine mammals was com- missioned to the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC) by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). To complete this task, the CCAC Standards Committee created the ad hoc subcommittee on marine mammals. We acknowledge and thank all the members of the subcommittee who worked together to develop, review, and guide this document through to publication: Dr. Pierre-Yves Daoust, University of Prince Edward Island Mr. John Ford, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Mr. Henrik Kreiberg, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Dr. Clément Lanthier, Calgary Zoo Dr. Kay Mehren, Veterinarian Emeritus, Toronto Zoo Ms. Tracy Stewart, Marineland of Canada Mr. Clint Wright, Vancouver Aquarium Dr. Gilly Griffin, Canadian Council on Animal Care We would also like to take this opportunity to recognize the dedication and vision of Dr. Jon Lien (Memo- rial University, deceased 2010), the Committee’s first Chair. Jon played a pivotal role in the creation of this document. It was the Lien Report: A review of live- capture and captivity of marine mammals in Canada that inspired DFO to request that CCAC develop recommendations for the care and maintenance of marine mammals. His vision became a collective goal - to improve the quality of life for all marine mammals held in captivity. -

A Summary of the Effects of Captivity on Orcas

A Summary of the Effects of Captivity on Orcas PEOPLE FOR THE ETHICAL TREATMENT OF ANIMALS Contents The Eff ects of Captivity on Tilikum and Orcas Generally at SeaWorld…………..................................…………......3 I. Orcas Are Extremely Intelligent Mammals Whose Brains Are Highly Developed in Areas Responsible for Complex Cognitive Functions, Including Self-Awareness, Social Cognition, Culture, and Language …………………………………………...............................................................................................…...4 II. Tilikum Is Deprived of Every Facet of His Culture and the Opportunity to Engage in Natural Behavior, Causing Extreme Stress and Suff ering….…………….….......................................................5 A. The Tanks at SeaWorld Provide Inadequate Space and Result in Stress……….…...........................5 B. SeaWorld’s Constant Manipulation of Tilikum’s Social Structure Results in Stress.................7 C. The Tanks at SeaWorld Create a Distressing Acoustic Environment…….………..….........................9 III. The Stressors of the Captive Environment at SeaWorld Result in Aggressiveness, Self- Injury, and Other Physical and Behavioral Abnormalities………………….……..............................................10 A. Aggression Between Orcas and Between Orcas and Humans……..……………..............................……10 B. Stereotypic Behavior………………….……………………………………….......................................................................….…..13 1. Painful Dental Problems Caused by Chewing Metal Gates and Concrete Tanks.....14 2. -

10 Worst Zoos for Elephants 2019

10 Worst Zoos for Elephants 2019 Zoo Domination of Elephants Must End For elephants, life in a zoo is one of continual domination by humans. Placed on perpetual display in cramped enclosures, deprived of purpose and subjected to endless boredom, unable to choose their mates or friends and often separated from those with whom they have bonded - these defining features of captivity demand the ceaseless bending of elephants' wills to their human captors. The cumulative effects of domination contributes to the physical and psychological trauma that often leads to illness and premature death. The zoos on this year's 10 Worst Zoos for Elephants list are striking examples of the different ways that zoos harmfully dominate elephants, including separating long-bonded individuals and family members, repeatedly forcibly inseminating females, and condemning others to lives of extremely unnatural solitude. In cold-climate facilities, elephants spend winters shut inside cramped indoor enclosures, many of which force elephants to stand on unyielding concrete which can lead to debilitating foot and leg diseases and even death. Zoos often downplay animal welfare concerns and conceal their harmful domination of elephants from the public. Through campaigns of misleading advertising and skewed educational programs, zoos frequently depict elephants as content, and pretend that elephants somehow agree to, and even enjoy these living conditions. Yet in reality, captive elephants suffer as many of their needs go unmet. Physical and psychological harm is virtually unavoidable in zoosʼ domination of elephants and is the reason zoos are unable to improve the health and wellbeing of elephants under their control. No amount of space, financial investment or “enrichment” in public display facilities takes away the daily pain that zoo captivity inflicts on elephants. -

Organization City State Admission Additional Discount

Organization City State Admission Additional Discount Calgary Zoo Calgary - Alberta Canada 50% Granby Zoo Granby - Quebec Canada 50% Toronto Zoo Toronto - Ontario Canada 50% Parque Zoologico de Leon Leon Mexico 50% Birmingham Zoo Birmingham Alabama 50% Alaska SeaLife Center Seward Alaska 50% The Phoenix Zoo Phoenix Arizona 50% Reid Park Zoo Tucson Arizona 50% Little Rock Zoo Little Rock Arkansas 50% Charles Paddock Zoo Atascadero California 50% Sequoia Park Zoo Eureka California 50% Fresno Chaffee Zoo Fresno California 50% Los Angeles Zoo Los Angeles California 50% Oakland Zoo Oakland California 50% The Living Desert Palm Desert California 50% Sacramento Zoo Sacramento California 50% Aquarium of the Bay San Francisco California 50% San Francisco Zoo San Francisco California 50% Happy Hollow Zoo San Jose California 50% CuriOdyssey (Coyote Point Museum) San Mateo California 50% Cabrillo Marine Aquarium San Pedro California FREE 10% discount at gift shop Santa Ana Zoo Santa Ana California 50% Santa Barbara Zoo Santa Barbara California 50% Pueblo Zoo Pueblo Colorado 50% Connecticut's Beardsley Zoo Bridgeport Connecticut 50% Smithsonian's National Zoological Park Washington DC DC FREE 10% discount at gift shops on-site Brandywine Zoo Wilmington Delaware 50% Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens Jacksonville Florida 50% Brevard Zoo Melbourne Florida 50% Zoo Miami Miami Florida 50% Central Florida Zoo & Botanical Gardens Sanford Florida 50% Mote Marine Aquarium Sarasota Florida 50% Saint Augustine Alligator Farm St. Augustine Florida 50% The Florida Aquarium