Community Protected Areas and the Conservation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle

THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Michelle Haughey August 2011 © 2011 Sarah Michelle Haughey THE ‘BESTLI’ OUTLAW: WILDERNESS AND EXILE IN OLD AND MIDDLE ENGLISH LITERATURE Sarah Michelle Haughey, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation, The ‘Bestli’ Outlaw: Wilderness and Exile in Old and Middle English Literature explores the reasons for the survival of the beast-like outlaw, a transgressive figure who highlights tensions in normative definitions of human and natural, which came to represent both the fears and the desires of a people in a state of constant negotiation with the land they inhabited. Although the outlaw’s shelter in the wilderness changed dramatically from the dense and menacing forests of Anglo-Saxon England to the bright, known, and mapped greenwood of the late outlaw romances and ballads, the outlaw remained strongly animalistic, other, and liminal, in strong contrast to premodern notions of what it meant to be human and civilized. I argue that outlaw narratives become particularly popular and poignant at moments of national political and ecological crisis—as they did during the Viking attacks of the Anglo-Saxon period, the epoch of intense natural change following the Norman Conquest, and the beginning of the market revolution at the end of the Middle Ages. Figures like the Anglo-Saxon resistance fighter Hereward, the exiled Marcher lord Fulk Fitz Waryn, and the brutal yet courtly Gamelyn and Robin Hood, represent a lost England imagined as pristine and forested. -

Costa Rica: National Parks & Tropical Forests January 19 - 31, 2019 (13 Days) with Hamilton Professor of Biology Emeritus Dr

Costa Rica: National Parks & Tropical Forests January 19 - 31, 2019 (13 Days) with Hamilton Professor of Biology Emeritus Dr. Ernest H. Williams An exclusive Hamilton Global Adventure for 16 alumni, parents, and friends. © by Don Mezzi © T R Shankar Raman © by Steve © by Lars0001 3 San Carlos Rio Frio Costa Rica Altamira Village Dear Hamilton Alumni, Parents, and Friends, Lake Arenal I am delighted to invite you to join me in January 2019 for Monteverde Tortuguero 3 Cloud Forest National Park a wonderful trip to Costa Rica. As we travel from volcanic Reserve Doka Estate mountain ranges to misty cloud forests and bountiful jungles, San José our small group of no more than sixteen travelers, plus an Hacienda 2 Nosavar Santa Ana expert local Trip Leader and me, will explore these habitats up- close. Quepos San Gerardo 2 The biodiversity found in Costa Rica is astonishing for a country with Manuel de Dota 2 Antonio an area of just 20,000 square miles (approximately four times the size of National Park Finca don Connecticut): more than 12,000 species of plants, including a dazzling variety Tavo of trees and orchids; 237 species of mammals, including jaguars and four Main Tour species of monkeys; more species of birds (800!) than in all of North America; Optional Extensions more species of butterflies than on the entire continent of Africa; and five # of Hotel Nights genera of sea turtles as well as the endangered American crocodile. Corcovado Airport Arrival/ National Park Our travels will merge daily nature observations with visits to Costa Rican Departure national parks, farms, villages, beaches, cloud forest, and the capital city, San Jose. -

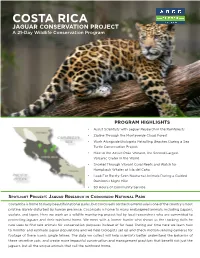

COSTA RICA JAGUAR CONSERVATION PROJECT a 21-Day Wildlife Conservation Program

COSTA RICA JAGUAR CONSERVATION PROJECT A 21-Day Wildlife Conservation Program PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS • Assist Scientists with Jaguar Research in the Rainforests • Zipline Through the Monteverde Cloud Forest • Work Alongside Biologists Patrolling Beaches During a Sea Turtle Conservation Project • Hike to the Active Poás Volcano, the Second Largest Volcanic Crater in the World • Snorkel Through Vibrant Coral Reefs and Watch for Humpback Whales at Isla del Caño • Look For Rarely-Seen Nocturnal Animals During a Guided Rainforest Night Hike • 30 Hours of Community Service SPOTLIGHT PROJECT: JAGUAR RESEARCH IN CORCOVADO NATIONAL PARK Costa Rica is home to many beautiful national parks, but Corcovado on the Osa Peninsula is one of the country’s most pristine. Barely disturbed by human presence, Cocorvado is home to many endangered animals, including jaguars, ocelots, and tapirs. Here we work on a wildlife monitoring project led by local researchers who are committed to protecting jaguars and their rainforest home. We meet with a former hunter who shows us the tracking skills he now uses to find rare animals for conservation purposes instead of for food. During our time here we learn how to monitor and estimate jaguar populations and we help biologists set up and check motion-sensing cameras for footage of these iconic jungle felines. The data we collect will help scientists better understand the behavior of these secretive cats, and create more impactful conservation and management practices that benefit not just the jaguars, but all the unique animals that call the rainforest home. SAMPLE ITINERARY DAY 1 TRAVEL DAY AND POAS VOLCANO Participants are met by their leaders in either Miami or San Jose, Costa Rica on the first day of the program (students have an option to take a group flight out of Miami). -

Integrity and Isolation of Costa Rica's National Parks and Biological Reserves

Biological Conservation 109 (2003) 123–135 www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Integrity and isolation of Costa Rica’s national parks and biological reserves: examining the dynamics of land-cover change G. Arturo Sa´ nchez-Azofeifaa,*, Gretchen C. Dailyb, Alexander S.P. Pfaffc, Christopher Buschd aDepartment of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Earth Observation Systems Laboratory, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E3 bDepartment of Biological Sciences, Center for Conservation Biology, 371 Serra Mall, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-5020 USA cDepartment of International and Public Affairs, Department of Economics, and Center for Environmental Research and Conservation, Columbia University, 420 W, 118th Streeet, Room 1306, New York, NY 10027 USA dDepartment of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Received 26 August 2001; received in revised form 11 February 2002; accepted 25 April 2002 Abstract The transformation and degradation of tropical forest is thought to be the primary driving force in the loss of biodiversity worldwide. Developing countries are trying to counter act this massive lost of biodiversity by implementing national parks and biological reserves. Costa Rica is no exception to this rule. National development strategies in Costa Rica, since the early 1970s, have involved the creation of several National Parks and Biological Reserves. This has led to monitoring the integrity of and interactions between these protected areas. Key questions include: ‘‘Are these areas’ boundaries respected?’’; ‘‘Do they create a functioning network?’’; and ‘‘Are they effective conservation tools?’’. This paper quantifies deforestation and secondary growth trends within and around protected areas between 1960 and 1997. We find that inside of national parks and biological reserves, deforestation rates were negligible. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Economy and Rhetoric of Exchange in Early Modern Spain Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5nf7w72p Author Ruiz, Eduardo German Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Economy and Rhetoric of Exchange in Early Modern Spain by Eduardo German Ruiz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Ignacio Navarrete, Chair Professor Emilie Bergmann Professor David Landreth Fall 2010 1 Abstract Economy and Rhetoric of Exchange in Early Modern Spain by Eduardo German Ruiz Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Ignacio Navarrete, Chair In this dissertation I analyze four canonical works (Lazarillo de Tormes, La Vida es Sueño, “El Celoso Extremeño,” and Heráclito Cristiano) with the goal of highlighting material- economic content and circumstantial connections that, taken together, come to shape selfhood and identity. I use the concept of sin or scarcity (lack) to argue that Lazarillo de Tormes grounds identity upon religious experience and material economy combined. In this process the church as institution depends on economic forces and pre-capitalistic profit motivations as well as rhetorical strategies to shape hegemonic narratives. Those strategies have economic and moral roots that, fused together through intimate exchanges, surround and determine the lacking selfhood represented by the title character. La Vida es Sueño begins with defective selfhoods, too. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Haec Templa: Religion in Cicero’s Orations A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY NICHOLAS ROBERT WAGNER IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Spencer Cole April 2019 © NICHOLAS WAGNER 2019 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my advisor, Spencer Cole, who provided helpful feedback and recommendations throughout the entire process of this dissertation and deserves singular acknowledgement. The project originated with a 2013 course on Roman religion. That, along with numerous meetings and emails, has been fundamental to my approach to the subject. I would also like to thank my other committee members, Christopher Nappa, Andrew Gallia, and Richard Graff, all of whom provided immensely useful feedback at various stages, both in the scope of the project and future directions to train my attention. Next, thanks are due to the faculty and the graduate students in the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Studies at the University of Minnesota. Their support over the years has been invaluable, both academically and socially. Special thanks are due to current student Joshua Reno and former student Rachael Cullick. Lunches with them, where they patiently heard my ideas in its earliest stages, will be ever-cherished. Finally, I would like to thank my parents and siblings for their endless support over the years. Sometimes a nice meal or a break at the movies is exactly what was needed. i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents and their parents. ii Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Cicero and Lived Religion ........................................................................................................ -

A VISIT to OSA MOUNTAIN VILLAGE Arrival in Costa Rica Navigating

TRAVEL TIPS: A VISIT TO OSA MOUNTAIN VILLAGE Arrival in Costa Rica This document will help you plan your trip to Osa Mountain Village and has been developed from the experience of many individuals who have come here in the past. The goal is to make it easy and relaxing for you by knowing what to expect and how to plan your trip. Planning ahead will help but you also do not have to have every detail accounted for as flexibility in your itinerary will also lend itself to an enjoyable trip. Contact Information: To call these numbers from the states you must dial 011-506 and the number. Jim Gale 8832-4898 Sales Ricardo 8718-3878 Sales - On-site Eric J & Bill H 8760-2168 Guest Services Skip 8705-7168 Sales - San José liaison Toll free from the USA and Canada for Guest Services: 888-68Osa Mt (888-686-7268) Be sure to coordinate your visit with Jim Gale or one of the Osa Mountain Village sales staff in advance. Osa Mountain Village is located in the South Pacific zone near the west coast. From San Jose you have the option to take a bus from the MUSOC bus terminal ($5) in San José for a 3 hour ride to the city of San Isidro de El General. There you can meet up with Jim, where he can drive you from San Isidro to Osa Mountain Village for the tour. Or you can rent your own car, and drive down to Osa Mountain Village yourself – meeting at the Osa Mountain Village & Canopy Tour office. -

The Factors for the Extinction of Jaguars and Cougars in El Salvador Michael Campbell* Department of Geography, Simon Fraser University Burnaby V5A 1S6, Canada

ioprospe , B cti ity ng rs a e n iv d d D o i e Campbell, J Biodivers Biopros Dev 2016, 3:1 v B e f l Journal of Biodiversity, Bioprospecting o o l p DOI: 10.4172/2376-0214.1000154 a m n r e n u t o J ISSN: 2376-0214 and Development ResearchReview Article Article OpenOpen Access Access The Factors for the Extinction of Jaguars and Cougars in El Salvador Michael Campbell* Department of Geography, Simon Fraser University Burnaby V5A 1S6, Canada Abstract The jaguar (Panthera onca, Linnaeus 1758) and cougar (Puma concolor, Linnaeus 1771) are the largest cats in the Americas and are listed as uniquely extinct in El Salvador, Central America. The contributory factors for this event are little understood and/or ignored. This omission hampers conservation planning for declining big cat populations in other countries. A thorough review and analysis of the literature reveals important gaps that impede assessment of the factors for big cat extinction, and also possible meliorative efforts. The evidence questions the commonly blamed civil war and deforestation, and critically assesses a wider set of factors mostly not linked to big cat extinction; dense human population, small national territory, border porosity, cat adaptability to modified land cover and the actual importance of connecting forested corridors. The evidence from other countries shows possibilities of cat adaptability to all possible factors for extinction, but also hints at the possibility of the lack of connecting corridors as uniquely negative in El Salvador. Reintroductions of big cats in El Salvador must include internationalized assessments of their ecology and public tolerance of cat presence. -

Revocation High on Fire Horrendous Monster

ONCE HUMAN FIT FOR A KING PYREXIA HORRENDOUS REVOCATION STAGE OF EVOLUTION DARK SKIES UNHOLY REQUIEM IDOL THE OUTER ONES EARMUSIC SOLID STATE RECORDS UNIQUE LEADER RECORDS SEASON OF MIST METAL BLADE Evolution was not just the title of Once Human’s No matter the pristine picture of self-worth we Long standing New York death metal legends Pyrexia Horrendous explode out of the underground with Pushing both the death metal and progressive elements sophomore release last year — it was an armor-plated project, in the unquenchable pursuit of recognition return with its newest and, arguably, most devastating its incredible new album Idol. Drawing inspiration of its signature sound harder than ever, The Outer Ones declaration. And it evolved into something big. Stage and affirmation, the gnawing anxiousness of guilt and album, Unholy Requiem. Recorded, mixed, and from both personal and national crises, Idol’s music represents Revocation at its boldest, most aggressive Of Evolution is the consequential mutation of the brokenness chews away at our spirits, uncovering mastered by guitarist Chris Basile, Unholy Requiem is a methodical and unapologetic take on dynamic, and complex. Moving away from the societal and Evolution album from studio to stage. “I know it’s new pain and vulnerability. Dark Skies is Fit For A finds Pyrexia revisiting its filthy, pulverizing, classic progressive death metal. Thematically, the ambitious historical themes that informed 2016’s Great is Our Sin, uncommon for a band who is not headlining to record King’s evocative declaration of a hard won victory. sound. Basile said of the album, “This album is definitely new album is an exploration of defeat, of the gods we vocalist/guitarist Dave Davidson has immersed himself a live album,” says Logan Mader, who metalheads “This album is far from happy. -

Costa Rica Discovery

COSTA RICA • WILDERNESS & WILDLIFE TOURS COSTA RICA Positioned between two continents, Costa Rica is home to more species of wildlife than any other place on earth: Scarlet Macaws, sea turtles, colourful fish, butterflies, monkeys and sloths to name a few. Active volcanoes tower above impenetrable jungle and the pristine seas are perfect for snorkelling. Keel Billed Toucan © Shutterstock Monteverde Sky Walk Hanging Bridge © Latin Trails Day 4 Arenal COSTA RICA Day at leisure to take advantage of the many DISCOVERY activities on offer. B Days 5/6 Monteverde 7 days/6 nights Travel by boat across the lake from Arenal to From $2896 per person twin share Monteverde. The rest of the afternoon is at leisure Departs daily ex San Jose to enjoy the many optional activates available. On day 6 enjoy a guided walk along the Sky Walk Price per person from:* Twin A Tortuga Lodge & Gardens/Arenal Nayara/ $4005 hanging bridges. Overnight in Monterverde. B Monteverde Lodge Day 7 Tour ends San Jose B Manatus Hotel/Tabacon Grand Spa/ $3140 Transfer by road to San Jose. Tour ends. B Nestled in Cloud Forest © El Establo Lodge Hotel Belmar C Mawamba Lodge/Lost Iguana/Hotel el Establo $2896 HOTEL EL ESTABLO *Min 2. Single travellers prices are available on request. Nestled in the misty Cloud Forest of Monteverde, this hotel combines adventure and relaxation. There INCLUSIONS Return scheduled road and boat transfers San Jose are plenty of unique experiences on offer, including to Tortuguero, private road transfer Tortuguero to the tree top canopy tour and exciting night walks Arenal/Monteverde, 6 nights accommodation, meals and in search of forest nightlife. -

High Altitude Cloud Forest: a Suitable Habitat for Sloths?

High altitude cloud forest: a suitable habitat for sloths? Wouter Meijboom Cloudbridge Nature Reserve October 3th, 2013 2 High altitude cloud forest: a suitable habitat for sloths? A field research on the suitability of a high altitude cloud forest in Costa Rica as a habitat for sloths. Student: Wouter Meijboom Organisation: Cloudbridge Nature Reserve External technical coach: Tom Gode University of applied science: Van Hall Larenstein Major coordinator and internal coach: Jaap de Vletter Date: October 3th, 2013 3 Abstract Protected areas play an important role in the conservation of biodiversity worldwide (Bruner, Gullison, Rice and da Fonseca 2000). Sloths (Bradypus variegatus and Choloepus hoffmanni) play a meaningful role in the ecosystems of the tropical forests of Costa Rica. This research focuses on Cloudbridge Nature Reserve (Cloudbridge NR), a protected area of 250 hectare tropical forest in South Central Costa Rica. The management of Cloudbridge NR wants to get back to the original state of the forest. Sloths used to live in and around Cloudbridge NR, but are not seen nowadays. That is why there is a wish to get sloths back in the area of Cloudbridge NR. This research is designed to investigate the possibilities for sloths to live again in Cloudbridge NR. The research question to investigate this is: Can Cloudbridge NR sustain an independent and healthy population of sloths? The methodology of this research consists of in depth interviews, literature reviews and a tree inventory using plots. Interviews and the literature study are used to identify the preferences of sloths and the possible threats to sloths. The interviews are also used to investigate the situation in the past, regarding to sloths in and around Cloudbridge NR. -

Ecoadventures Central American Travel Brochure Third Edition

to Costa Rica… Welcome National Parks, Biological & Wildlife Reserves and Protected Areas Highlands: 1 Braulio Carrillo National Park 2 Arenal National Park 3 Monteverde Biological Reserve Caribbean Coast: 4 Tortugero National Park 5 Cahuita National Park Pacific Coast: 6 Guanacaste National Park 7 Rincon de la Vieja National Park 8 Las Baulas Protected Area (turtle nesting beach) 9 Tamarindo Wildlife Refuge 10 Carara Biological Reserve 11 Manuel Antonio National Park 12 Corcovado National Park COSTA RICA COSTA PAGE San Jose Hotels & Activities 6 F riendly, peaceful Costa Rica has an immense range of climates, Xandari Plantation & Peace Lodge 7 flora and fauna of particular interest to naturalists from around La Selva Verde & Pacuare Lodge 8, 9 the world. In 1948 Costa Rica voted to abolish its army and today proudly spends 60% of its budget on social services. It boasts a Caribbean Coast high level of sanitation and education, and is one of the most Tortuguero, Puerto Viejo/Punta Cocles 9, 10 literate nations on earth. Highlands of Costa Rica Deeply committed to ecology, Costa Rica has set aside nearly 30% Arenal 11-13 of its land as national parks or as private reserves. It has long, Monteverde 14, 15 sandy beaches on both coasts which are ideal for an active or relaxing vacation. Costa Rica is an excellent family destination. Pacific Coast Once you have savored the misty mountains, tropical rainforests, Northern Pacific: Tamarindo & Papagayo 16, 17 and warm, friendly “Ticos,” you will wonder why you stayed away Central Pacific: Jaco, Esterillos, Herradura 18 so long! Southern Pacific: Quepos/Manuel Antonio 19, 20 Osa Peninsula: Lapa Rios & Casa Corcovado 21 Suggested Itineraries 22-25 4.