Integrity and Isolation of Costa Rica's National Parks and Biological Reserves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica: National Parks & Tropical Forests January 19 - 31, 2019 (13 Days) with Hamilton Professor of Biology Emeritus Dr

Costa Rica: National Parks & Tropical Forests January 19 - 31, 2019 (13 Days) with Hamilton Professor of Biology Emeritus Dr. Ernest H. Williams An exclusive Hamilton Global Adventure for 16 alumni, parents, and friends. © by Don Mezzi © T R Shankar Raman © by Steve © by Lars0001 3 San Carlos Rio Frio Costa Rica Altamira Village Dear Hamilton Alumni, Parents, and Friends, Lake Arenal I am delighted to invite you to join me in January 2019 for Monteverde Tortuguero 3 Cloud Forest National Park a wonderful trip to Costa Rica. As we travel from volcanic Reserve Doka Estate mountain ranges to misty cloud forests and bountiful jungles, San José our small group of no more than sixteen travelers, plus an Hacienda 2 Nosavar Santa Ana expert local Trip Leader and me, will explore these habitats up- close. Quepos San Gerardo 2 The biodiversity found in Costa Rica is astonishing for a country with Manuel de Dota 2 Antonio an area of just 20,000 square miles (approximately four times the size of National Park Finca don Connecticut): more than 12,000 species of plants, including a dazzling variety Tavo of trees and orchids; 237 species of mammals, including jaguars and four Main Tour species of monkeys; more species of birds (800!) than in all of North America; Optional Extensions more species of butterflies than on the entire continent of Africa; and five # of Hotel Nights genera of sea turtles as well as the endangered American crocodile. Corcovado Airport Arrival/ National Park Our travels will merge daily nature observations with visits to Costa Rican Departure national parks, farms, villages, beaches, cloud forest, and the capital city, San Jose. -

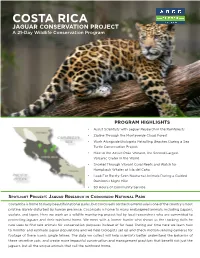

COSTA RICA JAGUAR CONSERVATION PROJECT a 21-Day Wildlife Conservation Program

COSTA RICA JAGUAR CONSERVATION PROJECT A 21-Day Wildlife Conservation Program PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS • Assist Scientists with Jaguar Research in the Rainforests • Zipline Through the Monteverde Cloud Forest • Work Alongside Biologists Patrolling Beaches During a Sea Turtle Conservation Project • Hike to the Active Poás Volcano, the Second Largest Volcanic Crater in the World • Snorkel Through Vibrant Coral Reefs and Watch for Humpback Whales at Isla del Caño • Look For Rarely-Seen Nocturnal Animals During a Guided Rainforest Night Hike • 30 Hours of Community Service SPOTLIGHT PROJECT: JAGUAR RESEARCH IN CORCOVADO NATIONAL PARK Costa Rica is home to many beautiful national parks, but Corcovado on the Osa Peninsula is one of the country’s most pristine. Barely disturbed by human presence, Cocorvado is home to many endangered animals, including jaguars, ocelots, and tapirs. Here we work on a wildlife monitoring project led by local researchers who are committed to protecting jaguars and their rainforest home. We meet with a former hunter who shows us the tracking skills he now uses to find rare animals for conservation purposes instead of for food. During our time here we learn how to monitor and estimate jaguar populations and we help biologists set up and check motion-sensing cameras for footage of these iconic jungle felines. The data we collect will help scientists better understand the behavior of these secretive cats, and create more impactful conservation and management practices that benefit not just the jaguars, but all the unique animals that call the rainforest home. SAMPLE ITINERARY DAY 1 TRAVEL DAY AND POAS VOLCANO Participants are met by their leaders in either Miami or San Jose, Costa Rica on the first day of the program (students have an option to take a group flight out of Miami). -

A VISIT to OSA MOUNTAIN VILLAGE Arrival in Costa Rica Navigating

TRAVEL TIPS: A VISIT TO OSA MOUNTAIN VILLAGE Arrival in Costa Rica This document will help you plan your trip to Osa Mountain Village and has been developed from the experience of many individuals who have come here in the past. The goal is to make it easy and relaxing for you by knowing what to expect and how to plan your trip. Planning ahead will help but you also do not have to have every detail accounted for as flexibility in your itinerary will also lend itself to an enjoyable trip. Contact Information: To call these numbers from the states you must dial 011-506 and the number. Jim Gale 8832-4898 Sales Ricardo 8718-3878 Sales - On-site Eric J & Bill H 8760-2168 Guest Services Skip 8705-7168 Sales - San José liaison Toll free from the USA and Canada for Guest Services: 888-68Osa Mt (888-686-7268) Be sure to coordinate your visit with Jim Gale or one of the Osa Mountain Village sales staff in advance. Osa Mountain Village is located in the South Pacific zone near the west coast. From San Jose you have the option to take a bus from the MUSOC bus terminal ($5) in San José for a 3 hour ride to the city of San Isidro de El General. There you can meet up with Jim, where he can drive you from San Isidro to Osa Mountain Village for the tour. Or you can rent your own car, and drive down to Osa Mountain Village yourself – meeting at the Osa Mountain Village & Canopy Tour office. -

The Factors for the Extinction of Jaguars and Cougars in El Salvador Michael Campbell* Department of Geography, Simon Fraser University Burnaby V5A 1S6, Canada

ioprospe , B cti ity ng rs a e n iv d d D o i e Campbell, J Biodivers Biopros Dev 2016, 3:1 v B e f l Journal of Biodiversity, Bioprospecting o o l p DOI: 10.4172/2376-0214.1000154 a m n r e n u t o J ISSN: 2376-0214 and Development ResearchReview Article Article OpenOpen Access Access The Factors for the Extinction of Jaguars and Cougars in El Salvador Michael Campbell* Department of Geography, Simon Fraser University Burnaby V5A 1S6, Canada Abstract The jaguar (Panthera onca, Linnaeus 1758) and cougar (Puma concolor, Linnaeus 1771) are the largest cats in the Americas and are listed as uniquely extinct in El Salvador, Central America. The contributory factors for this event are little understood and/or ignored. This omission hampers conservation planning for declining big cat populations in other countries. A thorough review and analysis of the literature reveals important gaps that impede assessment of the factors for big cat extinction, and also possible meliorative efforts. The evidence questions the commonly blamed civil war and deforestation, and critically assesses a wider set of factors mostly not linked to big cat extinction; dense human population, small national territory, border porosity, cat adaptability to modified land cover and the actual importance of connecting forested corridors. The evidence from other countries shows possibilities of cat adaptability to all possible factors for extinction, but also hints at the possibility of the lack of connecting corridors as uniquely negative in El Salvador. Reintroductions of big cats in El Salvador must include internationalized assessments of their ecology and public tolerance of cat presence. -

Costa Rica Discovery

COSTA RICA • WILDERNESS & WILDLIFE TOURS COSTA RICA Positioned between two continents, Costa Rica is home to more species of wildlife than any other place on earth: Scarlet Macaws, sea turtles, colourful fish, butterflies, monkeys and sloths to name a few. Active volcanoes tower above impenetrable jungle and the pristine seas are perfect for snorkelling. Keel Billed Toucan © Shutterstock Monteverde Sky Walk Hanging Bridge © Latin Trails Day 4 Arenal COSTA RICA Day at leisure to take advantage of the many DISCOVERY activities on offer. B Days 5/6 Monteverde 7 days/6 nights Travel by boat across the lake from Arenal to From $2896 per person twin share Monteverde. The rest of the afternoon is at leisure Departs daily ex San Jose to enjoy the many optional activates available. On day 6 enjoy a guided walk along the Sky Walk Price per person from:* Twin A Tortuga Lodge & Gardens/Arenal Nayara/ $4005 hanging bridges. Overnight in Monterverde. B Monteverde Lodge Day 7 Tour ends San Jose B Manatus Hotel/Tabacon Grand Spa/ $3140 Transfer by road to San Jose. Tour ends. B Nestled in Cloud Forest © El Establo Lodge Hotel Belmar C Mawamba Lodge/Lost Iguana/Hotel el Establo $2896 HOTEL EL ESTABLO *Min 2. Single travellers prices are available on request. Nestled in the misty Cloud Forest of Monteverde, this hotel combines adventure and relaxation. There INCLUSIONS Return scheduled road and boat transfers San Jose are plenty of unique experiences on offer, including to Tortuguero, private road transfer Tortuguero to the tree top canopy tour and exciting night walks Arenal/Monteverde, 6 nights accommodation, meals and in search of forest nightlife. -

High Altitude Cloud Forest: a Suitable Habitat for Sloths?

High altitude cloud forest: a suitable habitat for sloths? Wouter Meijboom Cloudbridge Nature Reserve October 3th, 2013 2 High altitude cloud forest: a suitable habitat for sloths? A field research on the suitability of a high altitude cloud forest in Costa Rica as a habitat for sloths. Student: Wouter Meijboom Organisation: Cloudbridge Nature Reserve External technical coach: Tom Gode University of applied science: Van Hall Larenstein Major coordinator and internal coach: Jaap de Vletter Date: October 3th, 2013 3 Abstract Protected areas play an important role in the conservation of biodiversity worldwide (Bruner, Gullison, Rice and da Fonseca 2000). Sloths (Bradypus variegatus and Choloepus hoffmanni) play a meaningful role in the ecosystems of the tropical forests of Costa Rica. This research focuses on Cloudbridge Nature Reserve (Cloudbridge NR), a protected area of 250 hectare tropical forest in South Central Costa Rica. The management of Cloudbridge NR wants to get back to the original state of the forest. Sloths used to live in and around Cloudbridge NR, but are not seen nowadays. That is why there is a wish to get sloths back in the area of Cloudbridge NR. This research is designed to investigate the possibilities for sloths to live again in Cloudbridge NR. The research question to investigate this is: Can Cloudbridge NR sustain an independent and healthy population of sloths? The methodology of this research consists of in depth interviews, literature reviews and a tree inventory using plots. Interviews and the literature study are used to identify the preferences of sloths and the possible threats to sloths. The interviews are also used to investigate the situation in the past, regarding to sloths in and around Cloudbridge NR. -

Ecoadventures Central American Travel Brochure Third Edition

to Costa Rica… Welcome National Parks, Biological & Wildlife Reserves and Protected Areas Highlands: 1 Braulio Carrillo National Park 2 Arenal National Park 3 Monteverde Biological Reserve Caribbean Coast: 4 Tortugero National Park 5 Cahuita National Park Pacific Coast: 6 Guanacaste National Park 7 Rincon de la Vieja National Park 8 Las Baulas Protected Area (turtle nesting beach) 9 Tamarindo Wildlife Refuge 10 Carara Biological Reserve 11 Manuel Antonio National Park 12 Corcovado National Park COSTA RICA COSTA PAGE San Jose Hotels & Activities 6 F riendly, peaceful Costa Rica has an immense range of climates, Xandari Plantation & Peace Lodge 7 flora and fauna of particular interest to naturalists from around La Selva Verde & Pacuare Lodge 8, 9 the world. In 1948 Costa Rica voted to abolish its army and today proudly spends 60% of its budget on social services. It boasts a Caribbean Coast high level of sanitation and education, and is one of the most Tortuguero, Puerto Viejo/Punta Cocles 9, 10 literate nations on earth. Highlands of Costa Rica Deeply committed to ecology, Costa Rica has set aside nearly 30% Arenal 11-13 of its land as national parks or as private reserves. It has long, Monteverde 14, 15 sandy beaches on both coasts which are ideal for an active or relaxing vacation. Costa Rica is an excellent family destination. Pacific Coast Once you have savored the misty mountains, tropical rainforests, Northern Pacific: Tamarindo & Papagayo 16, 17 and warm, friendly “Ticos,” you will wonder why you stayed away Central Pacific: Jaco, Esterillos, Herradura 18 so long! Southern Pacific: Quepos/Manuel Antonio 19, 20 Osa Peninsula: Lapa Rios & Casa Corcovado 21 Suggested Itineraries 22-25 4. -

Panama to Costa Rica PRISTINE PARKS ABOARD the VOYAGER FEBRUARY 22 – MARCH 4, 2019 Corcovado National Park

Panama to Costa Rica PRISTINE PARKS ABOARD THE VOYAGER FEBRUARY 22 – MARCH 4, 2019 Corcovado National Park Emberá village Bay-headed tanager Orchid MASSACHUSETTS AUDUBON Mass Audubon’s roots were established in 1896 by Founding Mothers Harriet Lawrence Hemenway and Minna B. Hall, who persuaded ladies of fashion to forgo the cruelly harvested plumage that adorned their hats. Noted ornithologist William Brewster was enlisted as the Massachusetts Audubon Society’s first president (1896-1913) to advance legislation to restrict the killing of birds and sale of their plumage. Environmental education and advocacy for conservation were driving forces from our beginnings. Mass Audubon continues 120+ years later, as a strong conservation leader. Mass Audubon Natural History Travel program began in the early 1960’s with the mission to share world-class birding with broader education about the natural world. We—as an organization and individuals—are deeply committed to getting people connected to nature. However, the effects of climate change are evident, and we, as travelers, are often conflicted with our desire to explore new places while wanting to be responsible stewards of the natural world. Mass Audubon works to fight climate change, but we know we can do even more. So in fall 2017, we teamed up with NativeEnergy to offset the carbon costs of all flights for Mass Audubon’s tours. NativeEnergy calculates the carbon footprint of all Mass Audubon tour related flights. These funds then finance carbon-reducing projects with strong social and environmental benefits. Fatimella Emesis butterfly Emberá children Turquoise-browed Motmot Three-toed sloth Yellow warbler Coiba National Park MASS AUDUBON HAS BEEN TAKING TRAVELERS TO COSTA RICA AND PANAMA FOR OVER 40 YEARS! But rarely do we get the opportunity to explore these fascinatingly diverse birding destinations by ship! This new and very special cruise - aboard the yacht Voyager - explores the rich Pacific coast – beginning at the world-famous Pipeline Road and remote Darién National Park in Panama. -

Annual Report 2020 2 a Message from the Executive Director

2020 Report Osa Birds Staff - Top Photo left to right: Andrea Johnson - Vice President Board of Directors; Pilar Bernal - Program Coordinator; Karen Leavelle - Director. Bottom Photo Left to right: Yolanda Staff Rodriguez, Assistant program Karen M. Leavelle, MSc.., Executive Director Coordinator; Nuria Urena Pizarro - Pilar Bernal Castro, Program Coordinator Assistant Program Coordinator. Yolanda Rodríguez Corrales, Assistant coordinator, Monitoring Program Rancho Quemado Nuria Ureña Pizzara, Assistant coordinator, Monitoring Program Rancho Quemado Research and Monitoring Personnel Víctor Rodríguez Mora Luz María Ureña Pizarro Nuria Ureña Pizzara Yolanda Rodríguez Corrales Neftalí Chavarría Villagra Edward Jesús Montiel Chavarría José Ángel Calderón Trejos Yendri Rojas Santamaria Arlet Quiros Calvo Board of Directors In This Report Andrea Johnson Guido Saborio The First Debt for Nature Swap 4 - 6 Nina Koch Black-cheeked Ant-Tanager Studies 7 - 8 Janina Schan Carissa Cox The MoSI Project 9 - 10 Nito Paniagua Karen Leavelle World Migratory Bird Day Festival (WMBD) 11 - 12 Audubon Christmas Bird Count (CBC) 13 - 14 Financials 15 Partners 15 Osa Birds needs your support! We want to thank you for all of the support you have shown to Osa Birds. We are grateful for your generous contributions. Please consider making a On the Cover: Broad-winged Hawk (Buteo contribution to help us fulfill our mission to protect birds and their habitats in Platypterus) is a Neotropical migratory bird that the Osa region of Costa Rica. Spread the word to friends and family as well! spends the winter months from Oct - April in You can ways to donate at www.osabirds.org. Costa Rica. Photo by: Dennis Atencio Osa Birds Annual Report 2020 2 A Message from the Executive Director Hello to our Dear Friends and Colleagues! We are so grateful for you, for your generous giving and shared love of birds, a senti- ment gown over time and compounded as we enter the holiday season. -

A Case Study of Oreros and the Corcovado National Park in Costa Rica

Dependent Environmentalism: A Case Study of Oreros and the Corcovado National Park in Costa Rica Scott Anderson State University of New York, Cortland I use the phrase "dependent environmentalism" to describe the process in which a conjuncture of three interests-local envi ronmental elites, international environmental elites, and the state-structures and shapes environmental conservation in less developed countries. In the case study presented, the imposi tion of a U.S. national park model and a U.S. environmental ethic of "wilderness thinking" in the establishment and man agement of Costa Rica's Corcovado National Park had deleteri ous effects on the local gold-mining-based economy and peas ant oreros (gold miners). This paper examines the environmen tal, economic, and social context of the park's establishment and demonstrates a need for more inclusive strategies of natu ral resource protection that show more concern for affected populations of rural poor. Introduction CosTA RicA IS for many reasons one of the most remarkable countries in the world. Two achievements set it apart: the abolition of a stand ing army after a civil war in 1948, and the dedication of its govern ment and leaders to environmental conservation and preservation. This paper takes a sympathetic but critical look at one of Costa Rica's celebrated environmental achievements. Costa Rica's achievements have, at least statistically, taken on ex traordinary dimensions. Over a period spanning just three decades, a succession of Costa Rican governments has set aside more than a fourth (28 percent) of the country as protected land. This includes 11 percent of the country in national parks (Figure 1), 4 percent in indigenous reserves, and 13 percent for a variety of purposes in cluding national forests, monuments, wildlife refuges, and biologi cal reserves. -

Dominical Tours & Activities 2021 Index

Dominical Tours & Activities 2021 Index Corcovado National Park..........3 Whales & Dolphins..........4 Snorkeling Cano Island..........5 Terraba-Sierpe Boat Mangrove..........6 Snorkeling Tour Ballena National Park..........7 Inshore - Fishing Trip - Half Day..........8 3 Corcovado National Park Jan 1 until Jul 1 until jun 30, 2021 nov 30, 2021 Adult Child Adult Child Rate Rate Rate Rate $160 $86 $161 $89 Duration: Full Day Minimum: 6 pax Includes: Bilingual certified guide, safety equipment, water, fresh tropical fruits, lunch, and the Corcovado National Park entrance fee. Difficulty Level: Hard What to bring: Small bags to safeguard personal belongings, sunscreen, hiking attire, swinsuit, towel, sandals or flip flops, during the rainy months (June to November) we recommend bringing a rain coat or poncho. Notes: Rates for children apply from 3 to 10 years. The Corcovado National Park Full Day Nature Tour departs from Punta Uvita at 7:00 AM and arrives approximately 1 ½ hours later at San Pedrillo Ranger Station in the Corcovado National Park. Upon arrival you will prepare for two guided nature tour hikes along two different trails and observe beautiful flora and fauna. Each hike takes around 2 hours. During the hikes you will be able to see many mammals such as spider, howler, and white-faced monkeys, sloths, coatis, raccoons, and tapirs as well as a great variety of birds, plants, and trees with over one hundred years of existence and in danger of extinction. After the first hike, we serve a picnic lunch near the San Pedrillo ranger station and then we begin the second trek. During boat transit from Punta Uvita beach to Corcovado National Park you may observe whales, dolphins, turtles, marine birds and fantastic views of the southern pacific Osa coastline. -

Central America 18.01.11 - 17.02.11 from Cancun (Mexico) to Belize and Guatemala

Central America 18.01.11 - 17.02.11 from Cancun (Mexico) to Belize and Guatemala. Central America 5.01.12- 21.03.12 from Cancun (Mexico) to Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Guatemala and Costa Rica. Dominique BRUGIERE In 2011 I arrived in Cancun (Mexico) and I have visited the following places: in Belize: Shipstern reserve near Sarteneja, Crooked Tree wildlife sanctuary, La Milpa station in Rio Bravo Conservation area, Cokscomb basin wildlife sanctuary west of Maya Centre. in Guatemala: Tikal national park, Biotopo del Quetzal south of Coban, Atitlan lake, Los Tarrales lodge at the base of Atitlan volcano, Corazon del Bosque reserve near Panajachel), Rio Dulce to Livingston of the atlantic coast. In 2012 I arrived again in Cancun (Mexico) where I stayed 5 days: I visited Coba and Chichen Itza, but except a few birds I have not seen any mammal. These places were crowded of tourists. I visited the following places: In Belize Cokscomb basin Wildlife Sanctuary, Monkey Bay and the Tropical Education Center. In Guatemala: Tikal, Biotopo del Quetzal, Los Tarrales Lodge, Monterrico. In Honduras I visited only Mountain of Celaque national park near Gracias, Cuero y Salado national park near la Ceiba, Cerro Azul y Meambar national park south of San Pedro de Sula. All these parks were very disappointing and I saw very few birds and just a few squirrels. Security is a problem everywhere; In Cuero y Salado and Cerro Azul y Meambar you are guarded by the army. I stayed only 8 days in this country. In Nicaragua I went to Cosinguine volcano reserve west of Leon, Lagunas de Apoyo and Masaya volcano, Lagunas de Apoyo near Masaya, Mambocho volcano near Granada, Isla de Ometepe in the middle of lake Nicaragua.