The Early Chicago Tall Office Building: Artistically and Functionally Considered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago from 1871-1893 Is the Focus of This Lecture

Chicago from 1871-1893 is the focus of this lecture. [19 Nov 2013 - abridged in part from the course Perspectives on the Evolution of Structures which introduces the principles of Structural Art and the lecture Root, Khan, and the Rise of the Skyscraper (Chicago). A lecture based in part on David Billington’s Princeton course and by scholarship from B. Schafer on Chicago. Carl Condit’s work on Chicago history and Daniel Hoffman’s books on Root provide the most important sources for this work. Also Leslie’s recent work on Chicago has become an important source. Significant new notes and themes have been added to this version after new reading in 2013] [24 Feb 2014, added Sullivan in for the Perspectives course version of this lecture, added more signposts etc. w.r.t to what the students need and some active exercises.] image: http://www.richard- seaman.com/USA/Cities/Chicago/Landmarks/index.ht ml Chicago today demonstrates the allure and power of the skyscraper, and here on these very same blocks is where the skyscraper was born. image: 7-33 chicago fire ruins_150dpi.jpg, replaced with same picture from wikimedia commons 2013 Here we see the result of the great Chicago fire of 1871, shown from corner of Dearborn and Monroe Streets. This is the most obvious social condition to give birth to the skyscraper, but other forces were at work too. Social conditions in Chicago were unique in 1871. Of course the fire destroyed the CBD. The CBD is unique being hemmed in by the Lakes and the railroads. -

Vol 16 No 6 Lincoln Building

PRESERVATIONAND CONSERVATIONASSOCIATION Volume 16 November-December, 1996 Number 6 Focus on: Lincoln Building Located at the southwest comer of East Main and Market streets in downtown Champaign, the Lincoln Building was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places for Architecture as a local- ly significant example of the Commercial Style. With its tripartite division of base, shaft, and capital; fixed storefront sash and second story display sash, each with transoms; and regularly spaced double- hung upper story windows, the Lincoln Building represents a state-of-the-art store/ office building for early twentieth century Champaign. Five stories tall and fireproof in construction, the mottled brown brick building with Oassical North and east elevations of the Lincoln Building, 44 East Main Street, Champaign. (Alice Revival inspired brown terra cotta trim Novak, 1996) and a copper cornice includes fine materials and solid construction, an ap- the style of these evolving late nineteenth Characteristics of the Commercial Style propriately handsome building built by and turn of the century buildings may be include a building height of five to six- one of Champaign's most prominent open to debate, but typically, some teen stories; steel skeleton construction families. The interior of the Linmln Build- variety of these buildings get lumped into with masonry wall surfaces; minimal, if ing features an extensive use of marble, the term "Commercial Style." Marcus any, projections from the facade plane; terrazzo, and wood trim in its office cor- Whiffen credits the first use of the term in flat roofs; level parapets or mrnices; 1/1 ridors of intact suites with single light print to an anonymous editor of four double-hung sash; prismatic transoms; doors and three-light interior corridor volumes of IndustriJlIChicago,published and minimal applied ornament. -

The Rookery Chicago Illinois

VOLUME 25 NUMBER 1 JANUARY-MARCH 1995 OFFICE THE ROOKERY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS PROJECT TYPE An outstanding restoration of a historic, century-old, 12-story office building. The developer's strategy was to restore the 293,962-square-foot building's historic architectural interiors on the ground and mezzanine levels and to incorporate state-of-the-art HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning), electrical, elevator, security, and telecommunications systems into the upper floors of office space without losing the feeling of the old building. This project sets the standard for future commercial renovations and proves that the cost of expensive, high-quality restoration can be recovered in Class A rents. SPECIAL FEATURES Historic preservation Landmark office building Successful conversion of a vacant, deteriorated building into modern Class A office space DEVELOPER Baldwin Development Company 209 South LaSalle Street, Suite 400 Chicago, Illinois 60604 312-553-6100 OWNER Rookery Partners Limited Partnership 209 South LaSalle Street, Suite 400 Chicago, Illinois 60604 312-553-6100 RESTORATION ARCHITECT McClier Corporation 401 East Illinois, Suite 625 Chicago, Illinois 60611 312-836-7700 GENERAL DESCRIPTION Following one of the most extensive restorations of a historic office building ever undertaken, the 109-year-old Rookery Building, located in the heart of Chicago's financial district, has reclaimed its former splendor. With painstaking exactitude, Baldwin Development Company and its restoration architect have brought back elements of the Rookery's three eras—Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root's original 1886 design, Frank Lloyd Wright's 1905 modernization of the interior, and a 1931 remodeling by William Drummond—while at the same time renovating the office floors to compete with the most expensive, recently constructed office space inside Chicago's Loop. -

The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

The Invisible Triumph: The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 JAMES V. STRUEBER Ohio State University, AT1 JOHANNA HAYS Auburn University INTRODUCTION from Engineering Magazine, The World's Columbian Exposition (WCE) was the first world exposition outside of Europe and was to Thus has Chicago gloriously redeemed the commemorate the four hundredth anniversary of obligations incurred when she assumed the Columbus reaching the New World. The exhibition's task of building a World's Fair. Chicago's planners aimed at exceeding the fame of the 1889 businessmen started out to prepare for a Paris World Exposition in physical size, scope of finer, bigger, and more successful enter- accomplishment, attendance, and profitability.' prise than the world had ever seen in this With 27 million attending equaling approximately line. The verdict of the jury of the nations 40% of the 1893 US population, they exceeded of the earth, who have seen it, is that it the Paris Exposition in all accounts. This was partly is unquestionably bigger and undoubtedly accomplished by being open on Sundays-a much finer, and now it is assuredly more success- debated moral issue-the attraction of the newly ful. Great is Chicago, and we are prouder invented Ferris wheel, cheap quick nationwide than ever of her."5 transportation provided by the new transcontinental railroad system all helped to make a very successful BACKGROUND financial plans2Surprisingly, the women's contribu- tion to the exposition, which included the Woman's Labeled the "White City" almost immediately, for Building and other women's exhibits accounted for the arrangement of the all-white neo-Classical and 57% of total exhibits at the exp~sition.~In addition neo-High Renaissance architectural style buildings railroad development to accommodate the exposi- around a grand court and fountain poolI6 the WCE tion, set the heart of American trail transportation holds an ironic position in American history. -

Office Buildings of the Chicago School: the Restoration of the Reliance Building

Stephen J. Kelley Office Buildings of the Chicago School: The Restoration of the Reliance Building The American Architectural Hislorian Carl Condit wrote of exterior enclosure. These supporting brackets will be so ihe Reliance Building, "If any work of the structural arl in arranged as to permit an independent removal of any pari the nineteenth Century anticipated the future, it is this one. of the exterior lining, which may have been damaged by The building is the Iriumph of the structuralist and funclion- fire or otherwise."2 alist approach of the Chicago School. In its grace and air- Chicago architect William LeBaron Jenney is widely rec- iness, in the purity and exactitude of its proportions and ognized as the innovator of the application of the iron details, in the brilliant perfection of ils transparent eleva- frame and masonry curtain wall for skyscraper construc- tions, it Stands loday as an exciting exhibition of the poten- tion. The Home Insurance Building, completed in 1885, lial kinesthetic expressiveness of the structural art."' The exhibited the essentials of the fully-developed skyscraper Reliance Building remains today as the "swan song" of the on its main facades with a masonry curtain wall.' Span• Chicago School. This building, well known throughout the drei beams supported the exterior walls at the fourth, sixth, world and lisled on the US National Register of Historie ninth, and above the tenth levels. These loads were Irans- Places, is presenlly being restored. Phase I of this process ferred to stone pier footings via the metal frame wilhout which addresses the exterior building envelope was com- load-bearing masonry walls.'1 The strueture however had pleted in November of 1995. -

Columbian Exposition Long Version

THE WORLD’S COLUMBIAN EXPOSITION OF 1893 QUEST CLUB PAPER JANUARY 7, 2011 JOHN STAFFORD 2 3 THE WORLD’S COLUMBIAN EXPOSITION OF 1893 QUEST CLUB PAPER JANUARY 7, 2011 JOHN STAFFORD Introduction It is my pleasure to have been able to research and now deliver this paper on the World’s Columbian Exposition that was held in Chicago during the summer of 1893. I offer a sincere thank you to Bill Johnson for having proposed the topic. My father was born in Chicago and was raised just a few blocks from the site of the Exposition. I too was born in the Windy City and spent the first eight years of my childhood there. My academic training and profession is that of a “city planner” and, in so many respects, the Columbian Exposition is one of the historic landmarks of city planning in the United States. Daniel Burnham, who was a seminal figure in the design of the Fair, is generally regarded as one of the early pioneers of the profession. I anticipated enjoying the research, and I certainly was not disappointed. I suspect that many of you in the audience today have read The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson. It was Quester Karen Goldner who recommended the book to me several years ago. I devoured it then and did so a second time in preparing this paper. But as Cheryl Taylor cautioned, just using the Devil in the White City for background would be way too easy for a Quest paper. I did do much additional reading, but I must admit no one comes close to bringing the Exposition and its characters to life than does Larson and his research was spot on. -

Large Commercial-Industrial and Tax - Exempt Users As of 7/10/2018

Large Commercial-Industrial and Tax - Exempt Users as of 7/10/2018 User Account User Charge Facility Name Address City Zip Number Classification 20600 208 South LaSalle LCIU 208 S LaSalle Street Chicago 60604 27686 300 West Adams Management, LLC LCIU 300 W Adams Street Chicago 60606 27533 5 Rabbit Brewery LCIU 6398 W 74th Street Bedford Park 60638 27902 9W Halo OpCo L.P. LCIU 920 S Campbell Avenue Chicago 60612 11375 A T A Finishing Corp LCIU 8225 Kimball Avenue Skokie 60076 10002 Aallied Die Casting Co. of Illinois LCIU 3021 Cullerton Drive Franklin Park 60131 26752 Abba Father Christian Center TXE 2056 N Tripp Avenue Chicago 60639 26197 Abbott Molecular, Inc. LCIU 1300 E Touhy Avenue Des Plaines 60018 24781 Able Electropolishing Company LCIU 2001 S Kilbourn Avenue Chicago 60623 26702 Abounding in Christ Love Ministries, Inc. TXE 14620 Lincoln Avenue Dolton 60419 16259 Abounding Life COGIC TXE 14615 Mozart Avenue Posen 60469 25290 Above & Beyond Black Oxide Inc LCIU 1027-29 N 27th Avenue Melrose Park 60160 18063 Abundant Life MB Church TXE 2306 W 69th Street Chicago 60636 16270 Acacia Park Evangelical Lutheran Church TXE 4307 N Oriole Avenue Norridge 60634 13583 Accent Metal Finishing Co. LCIU 9331 W Byron Street Schiller Park 60176 26289 Access Living TXE 115 W Chicago Avenue Chicago 60610 11340 Accurate Anodizing LCIU 3130 S Austin Blvd Cicero 60804 11166 Ace Anodizing & Impregnating Inc LCIU 4161 Butterfield Road Hillside 60162 27678 Acme Finishing Company, LLC LCIU 1595 E Oakton Street Elk Grove Village 60007 18100 Addison Street -

Designated Historic and Natural Resources Within the I&M Canal

Designated historic and natural resources within the I&M Canal National Heritage Corridor Federal Designations National Cemeteries • Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery National Heritage Areas • Abraham Lincoln National Heritage Area National Historic Landmarks • Adler Planetarium (Chicago, Cook County) • Auditorium Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Carson, Pirie, Scott, and Company Store (Chicago, Cook County) • Chicago Board of Trade Building (LaSalle Street, Chicago, Cook County) • Depriest, Oscar Stanton, House (Chicago, Cook County) • Du Sable, Jean Baptiste Point, Homesite (Chicago, Cook County) • Glessner, John H., House (Chicago, Cook County) • Hegeler-Carus Mansion (LaSalle, LaSalle County) • Hull House (Chicago, Cook County) • Illinois & Michigan Canal Locks and Towpath (Will County) • Leiter II Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Marquette Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Marshall Field Company Store (Chicago, Cook County) • Mazon Creek Fossil Beds (Grundy County) • Old Kaskaskia Village (LaSalle County) • Old Stone Gate, Chicago Union Stockyards (Chicago, Cook County) • Orchestra Hall (Chicago, Cook County) • Pullman Historic District (Chicago, Cook County) • Reliance Building, (Chicago, Cook County) • Rookery Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Shedd Aquarium (Chicago, Cook County) • South Dearborn Street-Printing House Row North (Chicago, Cook County) • S. R. Crown Hall (Chicago, Cook County) • Starved Rock (LaSalle County) • Wells-Barnettm Ida B., House (Chicago, Cook County) • Williams, Daniel Hale, House (Chicago, Cook County) National Register of Historic Places Cook County • Abraham Groesbeck House, 1304 W. Washington Blvd. (Chicago) • Adler Planetarium, 1300 S. Lake Shore Dr., (Chicago) • American Book Company Building, 320-334 E. Cermak Road (Chicago) • A. M. Rothschild & Company Store, 333 S. State St. (Chicago) • Armour Square, Bounded by W 33rd St., W 34th Place, S. Wells Ave. and S. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name West Loop - LaSalle Street Historic District other names/site number 2. Location Roughly bounded by Wacker Drive, Wells Street, Van Buren Street street & number and Clark Street N/A not for publication N/A city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois code IL county Cook code 031 zip code 60601-60604 60606, 60610 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Signature of certifying official/Title Date State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

The 150 Favorite Pieces of American Architecture

The 150 favorite pieces of American architecture, according to the public poll “America’s Favorite Architecture” conducted by The American Institute of Architects (AIA) and Harris Interactive, are as follows. For more details on the winners, visit www.aia150.org. Rank Building Architect 1 Empire State Building - New York City William Lamb, Shreve, Lamb & Harmon 2 The White House - Washington, D.C. James Hoban 3 Washington National Cathedral - Washington, D.C. George F. Bodley and Henry Vaughan, FAIA 4 Thomas Jefferson Memorial - Washington D.C. John Russell Pope, FAIA 5 Golden Gate Bridge - San Francisco Irving F. Morrow and Gertrude C. Morrow 6 U.S. Capitol - Washington, D.C. William Thornton, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Charles Bulfinch, Thomas U. Walter FAIA, Montgomery C. Meigs 7 Lincoln Memorial - Washington, D.C. Henry Bacon, FAIA 8 Biltmore Estate (Vanderbilt Residence) - Asheville, NC Richard Morris Hunt, FAIA 9 Chrysler Building - New York City William Van Alen, FAIA 10 Vietnam Veterans Memorial - Washington, D.C. Maya Lin with Cooper-Lecky Partnership 11 St. Patrick’s Cathedral - New York City James Renwick, FAIA 12 Washington Monument - Washington, D.C. Robert Mills 13 Grand Central Station - New York City Reed and Stern; Warren and Wetmore 14 The Gateway Arch - St. Louis Eero Saarinen, FAIA 15 Supreme Court of the United States - Washington, D.C. Cass Gilbert, FAIA 16 St. Regis Hotel - New York City Trowbridge & Livingston 17 Metropolitan Museum of Art – New York City Calvert Vaux, FAIA; McKim, Mead & White; Richard Morris Hunt, FAIA; Kevin Roche, FAIA; John Dinkeloo, FAIA 18 Hotel Del Coronado - San Diego James Reid, FAIA 19 World Trade Center - New York City Minoru Yamasaki, FAIA; Antonio Brittiochi; Emery Roth & Sons 20 Brooklyn Bridge - New York City John Augustus Roebling 21 Philadelphia City Hall - Philadelphia John McArthur Jr., FAIA 22 Bellagio Hotel and Casino - Las Vegas Deruyter Butler; Atlandia Design 23 Cathedral of St. -

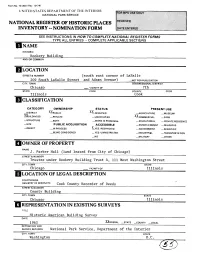

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ INAME HISTORIC Rookery Building___________________________________. AND/OR COMMON I LOCATION STREET & NUMBER (south east corner of LaSalle 209 South LaSalle Street and Adams Avenue) _NOTFOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Chicago _ VICINITY OF 7th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois Cook HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE YV _ DISTRICT ^PUBLIC A*_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE _ MUSEUM ^UILDING(S) __PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^COMMERCIAL _ PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME J. Parker Hall (land leased from City of Chicago) STREET& NUMBER Trustee under Rookery Building Trust A, 111 West Washington Street CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago VICINITY OF Illinois [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Cook County Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER ___County Building CITY, TOWN STATE Chicago Illinois REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Building Survey DATE 1963 XJ^EDERAL STATE _COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service, Department of the Interior CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS XX.ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Completed in 1886 at a cost of $1,500,000, the Rookery contained 4,765,500 cubic feet of space. -

Historic Greystone at 1463 Berwyn Avenue Saved!

Preservation Chicago Month-In-Review Newsletter October 2017 Historic Greystone at 1463 Berwyn Avenue Saved! 1436 W. Berwyn Avenue, Photo Credit Redfin UPDATE: The intense, sustained and widespread opposition to the planned demolition and redevelopment of the historic greystone at 1436 W. Berwyn Avenue has yielded a likely victory. The historic greystone at 1436 W. Berwyn Avenue is under contract to a new preservation-sensitive buyer who has plans to deconvert the two flat to a single family home and to restore its historic features. Additionally, the landscaped side yard and mature elm tree will be preserved. The sale of this historic property removes the property from the immediate threat posed by development plans to build out the site and create six-unit building with elements of the historic façade incorporated into the new construction. Without any historic landmark district protections and with existing zoning that allowed for a much larger, more dense building as-of-right, the path to a preservation outcome was highly unlikely. However, the extraordinary rapid response preservation advocacy efforts of Kathy Klink-Flores of the Lakewood Balmoral Residents Council, the East Andersonville Residents Council (EARC), Maureen Murnane of the Lakewood Balmoral Residents Council, and other community members and community organizations, which included well-attended public meetings, a petition drive, and other community organizing efforts deserves much of credit for this excellent preservation outcome. Page 1 of 38 Preservation Chicago Month-In-Review Newsletter October 2017 Preservation Chicago applauds the consistent support and leadership of 48th Ward Alderman Harry Osterman who played an important role in the preservation effort and outcome.