Pipestone NM, Final General Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota Emergency Alert System Statewide Plan 2016

Minnesota Emergency Alert System Statewide Plan 2016 MINNESOTA EAS STATEWIDE PLAN Revision 9 Basic Plan 11/9/2016 I. REASON FOR PLAN The State of Minnesota is subject to major emergencies and disasters, natural, technological and criminal, which can pose a significant threat to the health and safety of the public. The ability to provide citizens with timely emergency information is a priority of emergency managers statewide. The Emergency Alert System (EAS) was developed by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to provide emergency information to the public via television, radio, cable systems and wire line providers. The Integrated Public Alert and Warning System, (IPAWS) was created by FEMA to aid in the distribution of emergency messaging to the public via the internet and mobile devices. It is intended that the EAS combined with IPAWS be capable of alerting the general public reliably and effectively. This plan was written to explain who can originate EAS alerts and how and under what circumstances these alerts are distributed via the EAS and IPAWS. II. PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVES OF PLAN A. Purpose When emergencies and disasters occur, rapid and effective dissemination of essential information can significantly help to reduce loss of life and property. The EAS and IPAWS were designed to provide this type of information. However; these systems will only work through a coordinated effort. The purpose of this plan is to establish a standardized, integrated EAS & IPAWS communications protocol capable of facilitating the rapid dissemination of emergency information to the public. B. Objectives 1. Describe the EAS administrative structure within Minnesota. (See Section V) 2. -

Tattler for Pdf 11/1

Volume XXIX • Number 5 • January 31, 2003 Grand Rapids Fall Book. Clear Channel’s Country WBCT is on top once again! WBCT 9.9-9.6, WSNX 8.1-6.8, WLAV 7.3-6.4, WOOD-FM THETHE 4.9-5.7, WOOD-AM 5.1-5.5, WLHT 4.6-5.2, WGRD 6.4-5.0, WKLQ 5.8- 4.7, WTRV 3.7-4.2, WBFX 3.8-4.0, WODJ 3.9-3.6, WJQK 2.5-2.8, WVTI MAIN STREET 2.8-2.3, WFGR 1.6-2.2, WBBL-AM 1.7-2.1, WMUS 1.5-1.8, WFUR 1.3- CommunicatorNetwork 1.7, WMJH-AM 1.6-1.3, WJNZ-AM 1.1-1.0, WTKG-AM 1.1-1.0, WHTC- AM 0.5-0.7, WGHN 0.5-0.7, WKWM-AM 0.5-0.6, WYGR-AM 1.2-0.6, A T T L E WYVN 0.4-0.5, WMRR 0.8-0.5. Fall books found in this TATTLER are TT A T T L E RR 12+ persons, 6A-12P, M-Su, 6A-mid, Summer 2002 – Fall 2002 com- parisons, unless otherwise noted. Copyright © 2002, The Arbitron Com- TheThe intersectionintersection ofof radioradio && musicmusic sincesince 19741974 pany. These results may not be used without permission from Arbitron. TomTom KayKay -- ChrisChris MozenaMozena -- BradBrad SavageSavage The Conclave gives the 2 minute warning!! Make that, the 2 week Congrats to former Conclave Board member – and longtime Conclave warning. The Conclave wants EVERYONE to know it is STILL accepting agenda committee head – Rob Sisco as he ascends to the post of Presi- applications from high school students throughout the Upper Midwest dent, Nielsen Music and COO, Nielsen Retail Entertainment Infor- and Great Lakes region interested in studying for a career in the radio or mation (REI). -

Minnesota Emergency Alert System Statewide Plan 2018

Minnesota Emergency Alert System Statewide Plan 2018 MINNESOTA EAS STATEWIDE PLAN Revision 10 Basic Plan 01/31/2019 I. REASON FOR PLAN The State of Minnesota is subject to major emergencies and disasters, natural, technological and criminal, which can pose a significant threat to the health and safety of the public. The ability to provide citizens with timely emergency information is a priority of emergency managers statewide. The Emergency Alert System (EAS) was developed by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to provide emergency information to the public via television, radio, cable systems and wire line providers. The Integrated Public Alert and Warning System, (IPAWS) was created by FEMA to aid in the distribution of emergency messaging to the public via the internet and mobile devices. It is intended that the EAS combined with IPAWS be capable of alerting the general public reliably and effectively. This plan was written to explain who can originate EAS alerts and how and under what circumstances these alerts are distributed via the EAS and IPAWS. II. PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVES OF PLAN A. Purpose When emergencies and disasters occur, rapid and effective dissemination of essential information can significantly help to reduce loss of life and property. The EAS and IPAWS were designed to provide this type of information. However; these systems will only work through a coordinated effort. The purpose of this plan is to establish a standardized, integrated EAS & IPAWS communications protocol capable of facilitating the rapid dissemination of emergency information to the public. B. Objectives 1. Describe the EAS administrative structure within Minnesota. (See Section V) 2. -

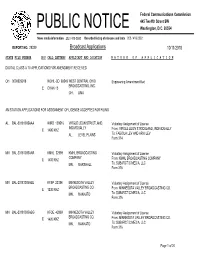

Broadcast Applications 10/11/2018

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 29339 Broadcast Applications 10/11/2018 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N DIGITAL CLASS A TV APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED OH 0000029918 WOHL-CD 68549 WEST CENTRAL OHIO Engineering Amendment filed BROADCASTING, INC. E CHAN-15 OH , LIMA AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING AL BAL-20181005AAA WIRB 129516 VIRGLE LEON STRICTLAND, Voluntary Assignment of License INDIVIDUALLY E 1490 KHZ From: VIRGLE LEON STRICKLAND, INDIVIDUALLY AL , LEVEL PLAINS To: FABIOLA LEV AND ARIK LEV Form 314 MN BAL-20181005AAR KMHL 32999 KMHL BROADCASTING Voluntary Assignment of License COMPANY E 1400 KHZ From: KMHL BROADCASTING COMPANY MN , MARSHALL To: SUBARCTIC MEDIA, LLC Form 316 MN BAL-20181005ABE KFSP 20386 MINNESOTA VALLEY Voluntary Assignment of License BROADCASTING CO. E 1230 KHZ From: MINNESOTA VALLEY BROADCASTING CO. MN , MANKATO To: SUBARCTIC MEDIA, LLC Form 316 MN BAL-20181005ABG KTOE 42899 MINNESOTA VALLEY Voluntary Assignment of License BROADCASTING CO. E 1420 KHZ From: MINNESOTA VALLEY BROADCASTING CO. MN , MANKATO To: SUBARCTIC MEDIA, LLC Form 316 Page 1 of 24 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 29339 Broadcast Applications 10/11/2018 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING HI BAL-20181005ABQ KUAI 58938 OHANA BROADCAST COMPANY Voluntary Assignment of License LLC E 570 KHZ From: OHANA BROADCAST COMPANY LLC HI , ELEELE To: PACIFIC RADIO GROUP, INC. -

Integrated Public Alert and Warning System Committee

STATEWIDE EMERGENCY COMMUNICATIONS BOARD INTEGRATED PUBLIC ALERT AND WARNING SYSTEM COMMITTEE Thursday, May 17, 2018 Call-in Number: 844-302-0362 1:00 – 3:00 p.m. Access Code: 745 498 588 Join WebEx Meeting WebEx password: IPAWS CHAIR: Trevor Hamdorf / VICE-CHAIR: Lillian McDonald MEETING LOCATION / WebEx and Conference Call AGENDA Call to Order Approval of Agenda Approval of Previous Meeting’s Minutes • April 2018 Announcements Standing Committee Reports • Policy Work Group ............................................................................................Lillian McDonald o Multi-lingual Survey Results • Infrastructure ........................................................................................................... John Dooley o Overview of EAS Report and Order from FCC 10APR18 o Overview of Stevens County Exercise Special Reports • Public Information .................................................................................. Amber Schindeldecker Old Business New Business • IPAWS Committee Strategic Planning for 2019-21 Session Outcomes ............. Discussion Item • IPAWS Committee Work Plan ............................................................................ Discussion Item o Identify / Choose leadership for the new work groups . Alerting Authorities . EAS Participants o Dividing up the work between the new workgroups o FCC addition of Blue Alert: planning for – course of action o EAS Plan Report and Order – changes that could affect our work plan timeline IPAWS Committee May 17, 2018 Page 1 STATEWIDE -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

Registration Information and Weather Related Announcements

Registration Information and Weather Related Announcements REGISTRATION FORMS Available on the appropriate page for conferences and competitions on our website, as well as in conference brochures. Complete form and email it, or print the form and then fax or mail it Submission of a registration is a commitment to participate and an obligation to pay the registration fee REGISTRATION DEADLINES AND FEES Register by early deadline for reduced fee No registrations accepted after the final deadline Districts may pay as they register or they will be billed after the event Parents must pay registration fees prior to conference CANCELLATION AND REFUND POLICY Cancellation requests must be postmarked (fax or mail) by final registration deadline for a refund, less a $10/person or $15/team service charge After the final deadline, no refunds will be processed (Thanks for understanding!) If a participant is unable to attend, send someone in their place and notify us of the change If you registered but do not attend, you are still responsible for payment ANNOUNCEMENTS Weather related announcements will be broadcast on the following radio stations: KARL FM 105.5 – Marshall KQIC FM 102.5 – Willmar KARZ FM 107.5 – Marshall KWLM AM 1340 – Willmar KKCK FM 99.7 – Marshall KITN FM 93.5 – Worthington KMHL AM 1400 – Marshall STUDENTS WITH SPECIAL NEEDS The SW/WC Service Cooperative, in accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), are dedicated to making conference activities accessible to all students. If a student has significant challenges, please contact Andrea for help in selecting appropriate classes and making needed accommodations prior to the final deadline. -

Cougar Chronicle for More Information

Cougar Chronicle October 16, 2019 Upcoming Events: No School: There will be no school on Thursday and Friday as our teachers will be attending the Minnesota District Teacher’s Conference at Bethany College in Mankato. Thur Oct 17 NO SCHOOL MVL Volleyball Tournament Champions! Congratulations to our Cougar volleyball team as they took first place in the MVL volleyball tournament last Saturday. Good job Fri Oct 18 girls and coaches! NO SCHOOL Sun Oct 20 Fire Poster Winners: Our school had winners for the Marshall Fire Department’s 8 & 10:30 am annual fire prevention poster contest. Anna Manian was named the 3rd grade winner Worship and Myra Kobylinski was named the overall winner! Way to go Anna and Myra! 9:15 am Sunday School MAP Testing: We began our standardized testing this week. We will again be using Wed Oct 23 MAP (Measures of Academic Progress) Testing which is done on the computers. Just a 8:30 am Chapel reminder that with these tests the questions will gradually get harder or easier depending on if students answer correctly or incorrectly to try and give a better indication of where each student is at academically. Each classroom will be staggering when they take the tests so that computers can be in each classroom for when they need to take the tests. We will get you the results of the testing once all the tests are complete and we have had time to review them. Please contact Mr. Obry with any questions. Cougar Wear: For those of you interested in ordering Samuel Lutheran Cougar wear, Borch's Sporting Goods has set up an online store for us. -

FY 2004 AM and FM Radio Station Regulatory Fees

FY 2004 AM and FM Radio Station Regulatory Fees Call Sign Fac. ID. # Service Class Community State Fee Code Fee Population KA2XRA 91078 AM D ALBUQUERQUE NM 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KAAA 55492 AM C KINGMAN AZ 0430$ 525 25,001 to 75,000 KAAB 39607 AM D BATESVILLE AR 0436$ 625 25,001 to 75,000 KAAK 63872 FM C1 GREAT FALLS MT 0449$ 2,200 75,001 to 150,000 KAAM 17303 AM B GARLAND TX 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KAAN 31004 AM D BETHANY MO 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KAAN-FM 31005 FM C2 BETHANY MO 0447$ 675 up to 25,000 KAAP 63882 FM A ROCK ISLAND WA 0442$ 1,050 25,001 to 75,000 KAAQ 18090 FM C1 ALLIANCE NE 0447$ 675 up to 25,000 KAAR 63877 FM C1 BUTTE MT 0448$ 1,175 25,001 to 75,000 KAAT 8341 FM B1 OAKHURST CA 0442$ 1,050 25,001 to 75,000 KAAY 33253 AM A LITTLE ROCK AR 0421$ 3,900 500,000 to 1.2 million KABC 33254 AM B LOS ANGELES CA 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KABF 2772 FM C1 LITTLE ROCK AR 0451$ 4,225 500,000 to 1.2 million KABG 44000 FM C LOS ALAMOS NM 0450$ 2,875 150,001 to 500,000 KABI 18054 AM D ABILENE KS 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KABK-FM 26390 FM C2 AUGUSTA AR 0448$ 1,175 25,001 to 75,000 KABL 59957 AM B OAKLAND CA 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KABN 13550 AM B CONCORD CA 0427$ 2,925 500,000 to 1.2 million KABQ 65394 AM B ALBUQUERQUE NM 0427$ 2,925 500,000 to 1.2 million KABR 65389 AM D ALAMO COMMUNITY NM 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KABU 15265 FM A FORT TOTTEN ND 0441$ 525 up to 25,000 KABX-FM 41173 FM B MERCED CA 0449$ 2,200 75,001 to 150,000 KABZ 60134 FM C LITTLE ROCK AR 0451$ 4,225 500,000 to 1.2 million KACC 1205 FM A ALVIN TX 0443$ 1,450 75,001 -

Plum Creek Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement

Plum Creek Wind Project Final Environmental Impact Statement The Human and Environmental Impacts of Constructing and Operating a 414 MW Wind Farm and Associated 345 kV Transmission Project April 2021 eDocket Nos. IP-6997/CN-18-699; IP-6997/WS-18-700; and IP-6997/TL-18-701 Abstract Responsible Government Unit Project Applicant Minnesota Department of Commerce Plum Creek Wind Farm, LLC Energy Environmental Review and 8400 Normandale Lake Blvd Analysis Suite 1200 85 7th Place East, Suite 280 Bloomington, MN 55437 Saint Paul, MN 55101 Department Representative Project Representatives William Cole Storm Melissa Schmit Environmental Review Manager Jenny Monson-Miller 651-539-1844 952-988-9000 [email protected] [email protected] Plum Creek Wind Farm, LLC (Plum Creek or Applicant) is proposing to build a 414-megawatt wind farm in Cottonwood, Murray, and Redwood Counties in southwest Minnesota. The applicant is also proposing to build approximately 30-mile long 345-kilovolt high-voltage transmission line to connect the wind farm to the electric grid. Plum Creek anticipates that construction will take approximately 12 months to complete, and the project will be in- service in late 2022. In order to build the project, Plum Creek must obtain three approvals from the Public Utilities Commission (Commission): a certificate of need (CN) for the project as a whole, a site permit for the wind farm, and a route permit for the transmission line. The purpose of this environmental impact statement (EIS) is to provide information the Commission needs to make these permit decisions. This final EIS addresses the issues and mitigation measures identified in the Department’s scoping decision of November 4, 2020 and reflects comments received on draft EIS (January 11, 2021). -

Annual EEO Public File Report Subarctic Media, Inc. Covering The

Annual EEO Public File Report Subarctic Media, Inc. Covering the Period from December, 2018 to November, 2019 Stations comprising Station Employment Unit KKCK-FM, KMHL-AM, KNSG-FM, KARZ-FM, KARL-FM Vacancy Information The following are all full-time job vacancies filled between December 1, 2018 and November 30, 2019, identified by job title and indicating the recruitment source that referred the successful candidate. Full-time Positions Total # Recruitment Recruitment Filled by Job Title DOE Interviewed Source of Hire Sources Utilized Market Manager 4/1/2019 2x Indeed .com Radio ads Indeed.com Facebook Personal Referral Account Executive 4/1/2019 2x Referral Radio ads Indeed.com Referrals Facebook Recruitment Sources: #Interviews Type Contact Address Method of Contact from Source 1. Marshall Radio Matt Ketelsen 255 Cedardale Drive Owatonna, MN 55060 507-444-9224 2 2. Indeed.com Christine Dyr 6433 Champion Grandview Way Austin, TX 78750 Website 1 3. Personal Referral 1 4. Facebook.com Molly Penny-Johnson www.facebook.com/KOWZFM Website 0 SUPPLEMENTAL RECRUITMENT INITATIVES – 2019 KKCK-FM, KMHL-AM, KNSG-FM, KARZ-FM, KARL-FM Internship- Two students from Marshall Senior High School conducted a job shadow experiences with Marshall Radio to gain knowledge on what a career in radio broadcasting would include. One job shadow experience was in sports broadcasting and the other was with the music director. Staff Members gave 3 group tours to local groups who wanted to see the radio station and learn about radio. Career Exploration Fair Staff member Keith Petermeier attended the 2019 Southwest Minnesota Careerforce Expo. The event involves 1800 students over two days from 30 high schools. -

Plum Creek Application, Nov 12 2019

Public Utilities Commission Route Permit Application for a 345 kV Transmission Line Plum Creek Wind Farm, LLC Docket No. IP6997 / TL-18-701 November 2019 Public Utilities Commission Application for Route Permit for a 345 kV Transmission Line Plum Creek Wind Farm, LLC Cottonwood, Murray, and Redwood Counties, Minnesota Docket No. IP6997 / TL-18-701 November 2019 7650 Edinborough Way Suite 725 Edina, MN 55435 Application for Route Permit Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 HVTL Project Ownership ........................................................................................... 1 1.2 Permittee ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Certificate of Need Process ......................................................................................... 2 1.4 State Routing Process .................................................................................................. 2 1.5 Request for Joint Proceeding with Certificate of Need Application ........................... 3 2.0 HVTL PROJECT INFORMATION ...................................................................................... 4 2.1 HVTL Project Proposal ............................................................................................... 4 2.2 Route Width ...............................................................................................................