PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joshua's Long Day - Skip to the Long Version

Joshua's Long Day - Skip to the Long Version Joshua 10 10:12 "Then spake Joshua to the LORD in the day when the LORD delivered up the Amorites before the children of Israel, and he said in the sight of Israel, sun stand thou still upon Gibeon; and thou, moon upon Ajalon. 10:13 And the sun stood still, and the moon stayed, until the people had avenged themselves upon their enemies. Is not this written in the book of Jasher? So the sun stood still in the midst of heaven, and hasted not to go down a whole day. 10:14 And there was no day like that before it or after it, that the LORD hearkened unto the voice of a man: for the LORD fought for Israel." NASA states on their web site: "According to the laws of physics, there are only two possible explanations for having the Sun stand still in the sky for a day: (1) the Earth would essentially have to stop spinning on its axis...for which there is no evidence. -or- (2) the Sun would have to start moving about in the solar system in a very specific way so that it appeared to us on our spinning Earth to be standing still. There is no evidence of this occurring either." The Sun standing still at noon for Joshua for a day may have been produced by God moving the Sun around the Earth. The history and the working model are given here. God may have moved the sun around the earth with earth's rotation to make the sun stand still in the sky. -

Underwater Antiquities INDEX

Die approbierte Originalversion dieser Diplom-/ Masterarbeit ist in der Hauptbibliothek der Tech- nischen Universität Wien aufgestellt und zugänglich. http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at The approved original version of this diploma or master thesis is available at the main library of the Vienna University of Technology. http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at/eng DIPLOMARBEIT MUSEUM OF UNDERWATER ANTIQUITIES MOUA ausgeführt zum Zwecke der Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Diplom-Ingenieurin unter der Leitung von O. Univ. Prof. Dipl. - Ing William Alsop Institut für Architektur und Entwerfen E253 Abteilung Hochbau und Entwerfen E253.4 eingereicht an der Technischen Universität Wien Fakultät für Architektur und Raumplanung von Despoina Charalampidou 1228419 Wien, am März 2015 DIPLOMARBEIT transformation of the old Cereals Stock house building Complex into a Museum of Underwater Antiquities. BETREUER O. Univ. Prof. Dipl. - Ing William Alsop _Acknowledgements I want to kindly thank my Prof. William Alsop for the important support and help he assisted me during the completion of my Diplomarbeit. Thank you for the helpful suggestions and the kind cooperation. The Diplomarbeit is dedicated to my Father. Kurzfassung Das neue Museum für Unterwasserantiquitäten befindet sich auf dem historischen Hafen von Piräus, auf der südöstlichen Seite der Ietonia Küste Docks und steht deswegen in direkter Verbindung mit dem Meer, den Reisen, der Entdeckung, den Expeditionen, der Erforschung, den Erkenntnissen und dem wachsenden Selbstbewusstsein. Ein Museum, das sich aus menschlichen Abenteuern, historischen Andenken und kollektiven Identitäten ergibt. Das Silo-Gebäude, ein bedeutendes Denkmal der griechischen Industriekultur und -tradition, wird weiterhin eine lebenden Zelle der Stadt sein, das für die neue Funktionalität des Hafens und die umfassenden Entwicklung- sziele im Bereich des Kulturtourismus angepasst wird. -

Humbler Craft: Rafts of the Egyptian Nile, 17Th-20Th Centuries AD’, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 40(2): 344-360

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Wiley Blackwell in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (IJNA), appearing online on 26 October 2010 and in print in Volume 40, Issue 2, in September 2011. The published version is available online at doi: 10.1111/j.1095- 9270.2010.00295.x. Please use the IJNA version in any citations: Cooper, J.P. 2011. ‘Humbler Craft: Rafts of the Egyptian Nile, 17th-20th Centuries AD’, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 40(2): 344-360 Humbler Craft: Rafts of the Egyptian Nile, 17th-20th Centuries AD John P. Cooper The MARES Project, Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, University of Exeter, Stocker Road, Exeter, EX4 4ND, UK, [email protected] Abstract Written accounts and images created by foreign travellers on the Egyptian Nile over the past four centuries indicate the widespread use of rafts and floats for both local and long-distance Nile travel. Many of the materials employed are poor survivors in archaeological deposits, or are otherwise easily overlooked as components of river-craft: moreover, several of these raft types were built for a single season or journey, then dismantled. Well- preserved wooden boats belonging to the pharaonic élite have commanded the attention of maritime archaeologists of the Nile. But these traveller accounts alert us to a class of vessels not yet recognized in archaeological deposits, and which point to a humbler quotidian experience of Nile navigation than the royal ships of antiquity. Key words: Egypt, Nile, Boat, Raft, Navigation, Landscape. Introduction When it comes to the watercraft of the Egyptian Nile, scholarly and popular attention has so far been drawn powerfully towards high-status, wooden- hulled vessels of the Pharaonic period. -

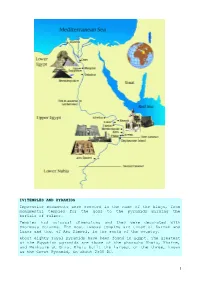

1 IV)TEMPLES and PYRAMIDS Impressive Monuments Were

IV)TEMPLES AND PYRAMIDS Impressive monuments were erected in the name of the kings, from monumental temples for the gods to the pyramids marking the burials of rulers. Temples had colossal dimensions and they were decorated with enormous columns. The most famous temples are those of Karnak and Luxor and that of Abu Simbel, in the south of the country. About eighty royal pyramids have been found in Egypt. The greatest of the Egyptian pyramids are those of the pharaohs Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure at Giza. Khufu built the largest of the three, known as the Great Pyramid, in about 2500 BC. 1 Pyramids The first Egyptian tombs were known as mastabas. These were rectangular structures of brick or stone built over a grave. The mastaba was the most popular tomb in the Old Kingdom. In about 2650 BC King Djoser built a step pyramid. The step pyramid is a series of stone rectangulars, one built on top of the other. In the early 26th century BC King Snefru built the first smooth-sided pyramid, at Meidum, 30 miles south of Memphis. Pharaohs built pyramids in the Old Kingdom and in the Middle Kingdom, but later rulers abandoned them in favour of less noticeable rock-cut tombs. New Kingdom pharaohs built these tombs in the Valley of the Kings. To date 62 tombs have been identified including that of Tutankamon. Giza is the site of some of the most impressive ancient monuments in the world. The greatest Egyptian pyramid at Gizah was built over a period of 20 years. Perhaps as many as 100,000 men built the pyramid. -

Walk to Jerusalem Spring Week 5 We Had Another Great Week This Week

Walk to Jerusalem Spring Week 5 We had another great week this week. We had 53 participants and walked 1072.5 miles! The map below shows our progress through the end of week five (purple line). At the end of week four we had arrived at Zahedan, Iran, just over the border from Pakistan. On Monday, March 1, we proceeded to trek across Iran, hoping to arrive in Iraq by Sunday. I had no idea when I planned this tour last November that the Pope would be in Iraq when we arrived, nor was I certain we would reach Iraq in time to see him in person but we did! A note about Persians versus Arabs: Iranians view themselves as Persian, not Arabs. Persia at one point was one of the greatest empires of all time (see map on page 2). From this great culture we gained beautiful art seen in the masterful woven Persian carpets, melodic poetic verse, and modern algebra. It is referred to as an “ancient” empire, but, in fact, some Persian practices, such as equal rights for men and women and the abolishment of slavery, were way ahead of their time. The Persian Solar calendar is one of the world’s most accurate calendar systems. Persians come from Iran while Arabs come from the Arabia Peninsula. The fall Persia’s great dynasty to Islamic control occurred from 633-656 AD. Since that time surrounding Arab nations have forced the former power to repeatedly restructure, changing former Persia into present day Iran. But with history and culture this rich, it is to no surprise that Persians want to be distinguished from others including their Arab neighbors. -

Languages by Date Before 1000 BC

Languages by Date Before 1000 BC Further information: Bronze Age writing Writing first appeared in the Near East at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. A very limited number of languages are attested in the area from before the Bronze Age collapse and the rise of alphabetic writing: the Sumerian, Hurrian, Hattic and Elamite language isolates, Afro-Asiatic in the form of the Egyptian and Semitic languages and Indo-European (Anatolian languages and Mycenaean Greek). In East Asia towards the end of the second millennium BC, the Sino- Tibetan family was represented by Old Chinese. There are also a number of undeciphered Bronze Age records: Proto-Elamite script and Linear Elamite the Indus script (claimed to record a "Harappan language") Cretan hieroglyphs and Linear A (encoding a possible "Minoan language")[3][4] the Cypro-Minoan syllabary[5] Earlier symbols, such as the Jiahu symbols, Vinča symbols and the marks on the Dispilio tablet, are believed to be proto-writing, rather than representations of language. Date Language Attestation Notes "proto-hieroglyphic" Egyptian hieroglyphs inscriptions from in the tomb of Seth- about 3300 BC c. 2690 BC Egyptian Peribsen (2nd (Naqada III; see Dynasty), Umm el- Abydos, Egypt, Qa'ab[6] Narmer Palette) Instructions of "proto-literate" period Shuruppak, the Kesh from about 3500 BC 26th century BC Sumerian temple hymn and (see Kish tablet); other cuneiform texts administrative 1 | P a g e Languages by Date from Shuruppak and records at Uruk and Abu Salabikh (Fara Ur from c. 2900 BC. period)[7][8] Some proper names attested in Sumerian A few dozen pre- texts at Tell Harmal Sargonic texts from from about 2800 c. -

ART and ARCHAEOLOGY Vocabulary ART and ARCHAEOLOGY Vocabulary Version 1.1 (Last Updated : Jan

- Institute for scientific and technical information - ART and ARCHAEOLOGY Vocabulary ART and ARCHAEOLOGY Vocabulary Version 1.1 (Last updated : Jan. 22, 2018) This resource contains 1960 entries. Controlled vocabulary used for indexing bibliographical records for the "Art and Archaeology" FRANCIS database (1972-2015, http://pascal-francis.inist.fr/ ). This vocabulary is browsable online at: https://www.loterre.fr Legend • Syn: Synonym. • →: Corresponding Preferred Term. • FR: French Preferred Term. • ES: Spanish Preferred Term. • DE: German Preferred Term. • URI: Concept's URI (link to the online view). This resource is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license: LIST OF ENTRIES List of entries English French Page • 10th century AD Xe siècle apr. J.-C. 46 • 10th dynasty Xe dynastie 46 • 11th century AD XIe siècle apr. J.-C. 46 • 11th century BC XIe siècle av. J.-C. 46 • 11th dynasty XIe dynastie 46 • 12th century AD XIIe siècle apr. J.-C 46 • 12th century BC XIIe siècle av. J.-C 46 • 12th dynasty XIIe dynastie 46 • 13th century AD XIIIe siècle apr. J.-C 46 • 13th century BC XIIIe siècle av. J.-C 46 • 13th dynasty XIIIe dynastie 46 • 14th century AD XIVe siècle apr. J.-C 46 • 14th century BC XIVe siècle av. J.-C 46 • 14th dynasty XIVe dynastie 46 • 15th century AD XVe siècle apr. J.-C 46 • 15th century BC XVe siècle av. J.-C 46 • 15th dynasty XVe dynastie 46 • 16th century AD XVIe siècle apr. J.-C 46 • 16th century BC XVIe siècle av. J.-C 46 • 16th dynasty XVIe dynastie 46 • 17th century AD XVIIe siècle apr. -

Sophiology As an Example of Integral Science and Education in the Slavonic Tradition

SOPHIOLOGY AS AN EXAMPLE OF INTEGRAL SCIENCE AND EDUCATION IN THE SLAVONIC TRADITION Emil Páleš Received December 4 2014 - Revised February 12 2015 - Accepted February 20 2015 ABSTRACT Several thinkers among the Slavs and in the Orthodox East have been led by the vision of Sophia – integral wisdom. Sophiology is an effort to integrate different sources of knowl- edge: revelation, reason and sensory experience. Its intention is to overcome the split among the psychic components of the human personality, which is echoed in the split among social processes and institutions. Such effort is of importance for the education of independent and morally responsible (wo)men and for the renewal of society’s weakened fundamental values. Sophiology’s basic intuition is the unity of creation; nature and society are shaped by the same beings or principles that are manifested and also operate within the human soul. Thanks to this, one can understand the external world by drawing on one’s inner ex- perience and vice versa, and give meaning to things by means of all-pervading analogies. This epistemological presupposition has been all but abandoned recently as a relic of a romantic or even older medieval way of thinking. In Slovakia, this has been reflected in the argument within the Štúrovci group concerning the principle of spiritual vision, which played a vital role in its Slavonic science project. We shall demonstrate that knowledge of this kind is still possible. It is possible, for ex- ample, to understand and effectively predict cultural epochs in history from the sequence and contents of psychic configurations during the biographical development of an indi- vidual. -

United States

Hanoi 191208 Wikipedia SyHung2020 United States From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses of terms redirecting here, see US (disambiguation), USA (disambiguation), and United States (disambiguation) The United States of America (commonly referred to as the United States, the U.S., the USA, or America) is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district. The country is situated mostly in central North America, where its forty-eight contiguous states and Washington, D.C., the capital district, lie between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, bordered by Canada to the north and Mexico to the south. The state of Alaska is in the northwest of the continent, with Canada to its east and Russia to the west across the Bering Strait. The state of Hawaii is an archipelago in the mid-Pacific. The country also possesses several territories, or insular areas, scattered around the Caribbean and Pacific. At 3.79 million square miles (9.83 million km²) and with about 305 million people, the United States is the third or fourth largest country by total area, and third largest by land area and by population. The United States is one of the world's most ethnically diverse and multicultural nations, the product of large-scale immigration from many countries.[7] The U.S. economy is the largest national economy in the world, with an estimated 2008 gross domestic product (GDP) of US$14.3 trillion (23% of the world total based on nominal GDP and almost 21% at purchasing power parity).[4][8] .. The nation was founded by thirteen colonies of Great Britain located along the Atlantic seaboard. -

Early Dynastic III a Dynasties ( = Historical Period) Ca

Chronology of the first half of the 3rd millennium IN Southern Mesopotamia According to excavations in the Diyala Valley: Early Dynastic I period: 2900–2750 BC Early Dynastic II period: 2750–2600 BC Early Dynastic III a period: 2600–2500 BC Early Dynastic III b period: ca. 2500–2334 BC According to Nippur startigraphy two phases: Early Dynastic I = I + II Early Dynastic III Predynastic kings before the deluge event according to the Sumerian King List "After the kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Eridug. In Eridug, Alulim became king; he ruled for 28800 years.„ Alulim 8 sars (28,800 years) Alalngar 10 sars (36,000 years) "Then Eridug fell and the kingship was taken to Bad-tibira." En-men-lu-ana 12 sars (43,200 years) En-men-gal-ana 8 sars (28,800 years) Dumuzid, the Shepherd "the shepherd" 10 sars (36,000 years) "Then Bad-tibira fell and the kingship was taken to Larag." En-sipad-zid-ana 8 sars (28,800 years) "Then Larag fell and the kingship was taken to Zimbir." En-men-dur-ana 5 sars and 5 ners (21,000 years) "Then Zimbir fell and the kingship was taken to Shuruppag." Ubara-Tutu 5 sars and 1 ner (18,600 years) "Then the flood swept over." Post-deluge dynasties (Early Dynastic I – II) according to the Sumerian King List First Dynasty of KISH after ca. 2900 BC "After the flood had swept over, and the kingship had descended from heaven, the kingship was in Kish.„ Ngushur 1200 years Kullassina-bel 960 years Nangishlishma 670 years En-tarah-ana 420 years Babum 300 years Puannum 840 years Kalibum 960 years Kalumum 840 years -

Sumer, Babylon, and Hittites 1

SUMER, BABYLON, AND HITTITES 1 Sumer, Babylon, and Hittites Get any book for free on: www.Abika.com Get any book for free on: www.Abika.com SUMER, BABYLON, AND HITTITES 2 Sumer, Babylon, and Hittites Sumer Sargon the Akkadian Sumerian Revival Sumerian Literature Epic of Gilgamesh Isin, Larsa, Eshnunna, Mari, Assur, and Babylon Hammurabi's Babylon Kassites, Hurrians, and Assyria Babylonian Literature Hittites Although cereals were being harvested with flint-bladed sickles and ground by limestone in the Nile valley more than 15,000 years ago, plants and animals were not domesticated for food until about 10,000 years ago in the fertile crescent of southwestern Asia and soon after that in Mesoamerica, Peru, and China. While the ice was melting and the climate was warming up, the reindeer and horses retreated to the north, and the mammoths disappeared. Forests spread, and those animals were replaced by red deer, wild pigs, and cattle. Dogs had already been domesticated for a few thousand years. Sedentary communities settled down in southwest Asia about a thousand years before wheat and barley were domesticated, supported by herds of wild sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs, which were all domesticated by 6000 BC. Women were probably responsible for learning how to cultivate plants, as they seemed to have done most of the plant gathering. Women also probably invented potting, spinning, and weaving. Men used to hunting probably took care of the herds and, after the plow was invented, castrated bulls to use oxen to pull plows and carts, though a Sumerian poem refers to a woman in the fields with the plow. -

Book of Centuries, They Are for Your Information on How to Use the Book

Mapping History A Timeline Book of the Centuries by Michele Quigley Contents: • Cover page • Introduction • Labeling worksheet sample • Blank labeling worksheet • 2 page spread sample pages - 13th century BC • 2 page spread sample pages - 13th century AD • Full color cover • Bookplate page • 3 blank pages • 48 lined, columned pages • 3 blank pages Printing Instructions: The left side of every page is intended to be blank. Therefore you will simply print this file as is and your book will be complete. After printing you can either 3 hole punch the pages and put them in a binder of take them to a printer to be bound together Please note: The first eight pages --cover page, introduction, labeling worksheets and sample pages-- are not meant to be included in the actual book of centuries, they are for your information on how to use the book. The Book of Centuries begins with the full color cover on page 9. © 2013 Michele Quigley. For Personal Use Only. Students in the PNEU schools would begin a “Book of the Centuries” around the age of 10 and keep the book throughout their school years. A child should have a concept of time and the past before beginning his centuries book. If you wish to begin earlier, you might consider making a “family” book of centuries. Each two page spread represents 100 years of history. The left side is blank, the right side is lined and columned. (see sample pages) On the right the child will record historical events, names and dates on and on the left he will make illustrations of artifacts, tools, pottery, clothing, etc., of the time period.