The Classical Catwalk: Fashioning the Ancient World on the Runway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtuososym Virtuoso Symposium South African Airways Cape Town 2016 Welcomes You to Cape Town

#VIRTUOSOSYM VIRTUOSO SYMPOSIUM SOUTH AFRICAN AIRWAYS CAPE TOWN 2016 WELCOMES YOU TO CAPE TOWN South Africa is delighted to host the 2016 Virtuoso Symposium. As the national April 17, 2016 carrier, South African Airways is honored to be chosen as the offi cial airline for the Symposium. We extend to you a warm welcome to Cape Town and thank you Dear Virtuosos, for your support. Welcome to Cape Town! How appropriate that we meet for our 36th annual Virtuoso Symposium in the Mother City, a destination known for its cultural diversity, warmth, and sense of community. When I first talked about communities last August at Virtuoso Travel Week, I quoted Simon Sinek’s definition: “A group who agrees to grow together.” In effect, we’re the 2016 Symposium community who are here to forge stronger bonds through shared travel experiences, so please take a moment to join me in thanking our Symposium sponsor partners who play such an integral role in how we’ll experience South Africa together. They’re all featured in the pages that follow. The Virtuoso Events team and our Cape Town hosts have really outdone themselves with spectacular venues and personal touches topped with a myriad of Design Your Day activities to fully immerse your- self in South Africa. Whether wine lands or peninsula, sidecar ride or city walk, philanthropic or retail therapy, we’ve got you covered. Of course, we have you covered on the business side of Symposium as well. We’ll hear from three com- pelling speakers: Eric McNulty – Director of Research, Harvard’s National Preparedness Leadership Ini- tiative, Dave Pavelko – Partnerships Director, Travel – Google Inc., and David Scowsill – President and CEO, World Travel & Tourism Council. -

INSIDE THIS ISSUE Fashion Lion

the Albright College FAshion DepArtment neWsletter • FAll 2011 FASHION LION What’s Hot at Albright? African Textile Design INSIDE THIS ISSUE Designers and Mass Marketing Meet the Faculty: Kendra Meyer, M.F.A. Letter from the Editor EVERYTHI NG by Mary Rose Davis ’15 Dear Readers, Welcome to our first issue of the Fashion OLD Lion! Previously, the fashion newsletter was Incorporating vintage fashion into modern looks is easy. called Seventh on Thirteenth, a play on words that mimicked Seventh on Sixth where “Thanks, it’s vintage,” is possibly one of the coolest things you can say when New York City’s Fashion Week was held receiving a compliment on your outfit. for many years. With the relocation of the With fashion trends from the past becoming more popular, it’s important to fashion week events uptown to the Lincoln know how to incorporate these trends into your style without looking “dated.” Center, we held a contest this semester to come up with a new Once you do, you’ll have a whole new — or old as the case may be — look. name for the newsletter. Congratulations to fashion design and First, you can’t wear it if you don’t own it. So get your fashionable self to the merchandising major Monica Tulay ’12 for the winning entry. closest thrift store or just raid your parents’ closet and find that perfect piece for For me, this change in name serves as a symbol of my years you. One thing to keep in mind is that it’s always easier to start with smaller items at Albright. -

CCP Coercion of U.S. Companies V3

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Coercion of U.S. Companies The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) frequently pressures and coerces U.S. compa- nies to conform to its political values and foreign policy. Because of China’s market size, individual companies often feel as though they have no option but to comply with CCP demands. 1. Tiffany & Co. (October 8, 2019) Tiffany & Co. removed a tweeted advertisement featuring a Chinese model wearing a Tiffany ring and covering her right eye with her right hand, a pose many Chinese social media accounts claimed referenced a pose that has come to be associated with the Hong Kong protest movement. 2. Activision Blizzard (October 8, 2019) Activision Blizzard suspended Hong Kong-based Chung Ng Wai, a professional player of one of its online games, after Chung expressed support for Hong Kong protesters in a post-game interview. In addition to making Chung ineligible to receive prize money he had earned in 2019, the company fired the two individuals who conducted the interview with Chung. 3. South Park (October 8, 2019) Comedy Central’s “South Park” was removed from major video streaming plat- forms in China after the cartoon aired an episode satirizing the PRC government’s retaliation against U.S. companies for statements in support of Hong Kong. 4. Houston Rockets/NBA (October 6-8, 2019) After Daryl Morey, General Manager of National Basketball Association (NBA) team the Houston Rockets, tweeted an image with the caption “Fight for Freedom. Stand with Hong Kong,” the PRC consulate in Houston “lodged representations” and demanded the team “correct the error” and “eliminate the adverse impact.” Soon thereafter, the Chinese Basketball Association, Chinese sportswear brand Li-Ning, Shanghai Pudong Development Bank Credit Card Center, Chinese tech companies Tencent and Vivo, and PRC state media outlet CCTV suspended cooperation with the team. -

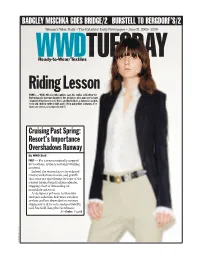

Riding Lesson

BADGLEY MISCHKA GOES BRIDGE/2 BURSTELL TO BERGDORF’S/2 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’TUESDAY Daily Newspaper • June 21, 2005• $2.00 Ready-to-Wear/Textiles Riding Lesson PARIS — While Nicolas Ghesquière says his cruise collection for Balenciaga is baroque-inspired, the designer also appears to have channeled the horsey set. Here, an illustration: a Javanese jacket, ecru silk chiffon ruffled shirt and cotton gabardine jodhpurs. For more on cruise, see pages 6 and 7. Cruising Past Spring: Resort’s Importance Overshadows Runway By WWD Staff PARIS — For a season originally inspired by vacations, cruise is certainly working overtime. Indeed, the season has so far eclipsed runway collections in scale and growth that some are questioning the logic of the current international fashion calendar, stopping short of demanding an immediate upheaval. As designers put more fashion into their pre-collection deliveries, retailers are less and less dependent on runway shipments to drive sales and profitability, said Jim Gold, Bergdorf Goodman’s See Cruise, Page8 PHOTO DOMINIQUE BY MAITRE 2 WWD, TUESDAY, JUNE 21, 2005 WWD.COM Badgley Mischka Sets Bridge Line By Rosemary Feitelberg decision was far from rash. enues that more people can af- WWDTUESDAY “We’ve been doing Badgley ford to buy,” Mischka said. Ready-to-Wear/Textiles NEW YORK — Spring, the sea- Mischka for 16 years. Yes, we’re Many customers can afford to son for renewal, has not been ready,” he said. “This is some- buy only one couture piece a sea- GENERAL lost on Mark Badgley and James thing we have wanted to do for a son even though they have many For a season originally inspired by vacations, cruise is certainly working Mischka, considering the pair long time. -

JANET HERNANDEZ 933 2Nd St

JANET HERNANDEZ 933 2nd St. #202 Santa Monica, CA 90403 . 3104036051 . [email protected] A focused independent self- starter, motivated, highly creative individual with great trend/fashion eye with passionate entrepreneurial-like views and opinions. Established an effective network within the fashion industry with key PR/marketers, thought-leaders, stylists, photographers and dreamers! PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE styleLUST August 2013 – Current Santa Monica, California Owner/Designer & Creative Consultant – Swimwear/Resortwear/Activewear/Sportswear • SPANX - Consultant & Creative Direction - Brand relaunch of Swimwear & Activewear • Erland Creative – Business Card Design Perry Ellis International – LAUNDRY by Shelli Segal /JANTZEN Los Angeles, California Designer - Swimwear/Cover-Ups/Resortwear March 2010 – Nov 2013 • Launched and managed the successful debut of Laundry by Shelli Segal Swimwear Cruise 2012. • Create a compelling lifestyle brand experience for consumers and buyers: Cruise/Spring/ Summer 2012, 2013 and currently 2014 collections (Laundry by Shelli Segal). • Responsible for steady market growth with leading vendors. • Design and direct Jantzen 2014 Cruise Collection as of Aug 2012-Nov 2013. • Manage and execute all aspects of design- from concept to production, trend research and development, color analysis and direction, print/fabric/trim design and development, draping, pattern and garment construction knowledge, garment fittings, targeting fit and quality problems, identify and resolve issues, manage and direct assistant -

Vogue Magazine the Glossy Has Spawned an Industry of Imitators, Two Documentaries, a Major Hollywood Film And, Perhaps Most Enduringly, a Modern Dance Craze

Lookout By the Numbers Vogue Magazine The glossy has spawned an industry of imitators, two documentaries, a major Hollywood film and, perhaps most enduringly, a modern dance craze. Itís also gone through some serious changes over the course of its 121 years in print. In recent years, the fashion bible has traded willowy models for celebrities of all kinds, a trend that reached its apex in April when the left-leaning, Chanel-shaded Brit Anna Wintour (the magazineís seventh editor in chief) decided to put ó gasp! ó a reality star on its cover. But even with young upstarts nipping at its Manolos, the periodical that popularized tights and the L.B.D. continues to thrive under its time-tested principle. That is, while other magazines 15 teach women whatís new in fashion, Vogue teaches them whatís in vogue. Approx. age at which Anna Wintour Here, a look at the facts and figures behind fashionís foremost franchise. — JEFF OLOIZIA established her signature bob $200,000 13% Wintour’s rumoredored annual clothing allowance of covers featuring celebrities during Wintour’s first five years 916 PagesP in the Favorite cover model by editor: SeptemberSepte 2012 issue, Anna Wintour: Vogue’sVogue largest to date 93% AMBER VALLETTA Vogue’sVoVogue’gue’ longest tenuredd editors:editors: of covers featuringg celebritiesc 17x over the last five years (still on the masthead)d) Diana Vreeland: Anna Wintour – 29 years A samplingsampling BRIGITTE BAUER Phyllis Posnick – 27 years of the 19 exotic exotic & animalsanimalsimals in fashionfashi on JEAN SHRIMPTON Grace Coddington – 26 years 19x each spreadsspreads Hamish Bowles – 22 years alongsideala ongside famous famous Reigning cover queen ladies:ladies:dies: 37 CheetahC (Kim Basinger, April ‘88) Number of years the longest ElephantEle (Keira Knightley, June ‘07) 26 reigning editor in chief served (Edna Woolman Chase, 1914-1951) SkunkSk (Reese Witherspoon, June ‘03) Number of times Lauren Hutton has fronted the magazine GibbonGi (Marisa Berenson, March ‘65) 8 (Nastassja Kinski, Oct. -

Versace's Native American

VERSACE’S NATIVE AMERICAN A COLONIZED FEMALE BODY IN THE NAME OF AESTHETIC AND DYNASTIC GLORY 1 In this contemporary moment fashion designers have the means to collaborate with Native American fashion designers. However, there is still a flourishing fashion market that refuses to recognize Native American tribes as owners of intellectual property.1 While some brands may initially start on the right track via collaboration with Native artists, it may not always end in success.2 Most recently, Versace has included Native American designs in their ready-to-wear fashion for the 2018 Spring-Summer season. This component of the collection belongs to a tribute honoring Gianni Versace and his original FW ’92 Native American print (Figures 1 and 2).3 I will be discussing the implications of the revived Native American print and how it affects Native North American men and women. In this essay, I will look at Versace’s legacy and his original print; the new Native American Tribute Collection by Donatella Versace; and Donna Karan’s collaboration with Pueblo artist, Virgil Ortiz. I argue that respectful recognition of Native North American property is thrown aside for aesthetic and dynastic glory, which in turn, allows non-Native designers to colonize the ‘exotic’ Native woman’s body by denying Native North American men and women the opportunity to represent themselves to the global fashion community. Virgil Ortiz’s collaboration with Donna Karan illustrates how respectful collaboration can shape the dominant society’s perception of Native North American women. If we use Native North American fashion as a framework to understand how Native designers are working to dismantle mainstream stereotypes, it is imperative that global designers 1 “Navajo Nation Sues Urban Outfitters,” Business Law Daily, March 18, 2012. -

Luxottica Admitted to the Cooperative Compliance Scheme with the Italian Revenue Agency

Luxottica admitted to the Cooperative Compliance scheme with the Italian Revenue Agency Milan, 29 December 2020 – Luxottica was admitted by the Italian Revenue Agency to the Cooperative Compliance scheme under legislative decree no. 128/2015. The aim of the Cooperative Compliance scheme, in accordance with current legislation to prevent tax risk and permit a further increase in the level of certainty regarding important fiscal matters, is to strengthen the relationship of trust and transparency between Luxottica and the Italian Revenue Agency. The admission to the scheme was preceded by an assessment performed by the Revenue Agency examining the full adequacy of Tax Governance and the Tax Control Framework adopted by Luxottica for the detection, measurement, management, and control of potential tax risk. Adherence to this regime is part of a wider Luxottica strategy aimed at the preventative management of risk based on transparency with financial administrations at a global level for the benefit of all stakeholders. Contacts: Oriana Pagano Group Corporate Media Relations Manager Email: [email protected] Luxottica Group S.p.A. About Luxottica Group Luxottica is a leader in the design, manufacture and distribution of fashion, luxury and sports eyewear. Its portfolio includes proprietary brands such as Ray-Ban, Oakley, Costa, Vogue Eyewear, Persol, Oliver Peoples and Alain Mikli, as well as licensed brands including Giorgio Armani, Burberry, Bulgari, Chanel, Coach, Dolce&Gabbana, Ferrari, Michael Kors, Prada, Ralph Lauren, Tiffany & Co., Valentino and Versace. The Group’s global wholesale distribution network covers more than 150 countries and is complemented by an extensive retail network of approximately 9,000 stores, with LensCrafters and Pearle Vision in North America, OPSM, LensCrafters and Spectacle Hut in Asia -Pacific, GMO and Óticas Carol in Latin America, Salmoiraghi & Viganò in Italy and Sunglass Hut worldwide. -

Virtuoso Members

VIRTUOSO MEMBERS Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 Group 4 Group 5 Aladdin Travel 6 Degrees 4 Seasons Travel Inc Alatur Viagens e Turismo Admiral Travel International, Inc. Andromeda Viajes Andavo Travel - Alabama Aldine Travel, Inc. All Aboard Travel, Inc. Andavo Travel Blue Skies Travel Assistant Privé au Voyage All World Travel, Inc. - Albuquerque Andrew Harper LLC Avenue Two Travel Boarding Pass Classic Travel Service, Inc. Allure Travel by CTM Anywhere Travel bcmviajes Charlotte Travel CoSport Brasil Atlàntida Viatges BTS Travel Group - Travel Experts Coastline Travel Advisors Creative Travel, Inc. Cruises Etc. Travel LLC Century Travel, Inc. CADENCE Colletts Travel Limited Direct Travel Luxe EFR Travel Group Cruise Vacations International Camelback Odyssey Travel Carlson Wagonlit Travel dnata Gateway Travel Service For Travelers Only Columbus Travel Distinctive Journeys Forest Travel Agency Helloworld Newcastle (HTG Corporate) Greatways Travel, Inc. First in Service Travel Executive Edge Travel + Events Global International Travel Service Jebsen Travel Group KK Travels Worldwide Great Getaways Travel Herff Travel, Inc. Global Travel Jim Eraso Travel, Inc. L'Espace Tours Huffman Travel, Ltd Lake Shore Travel Manchester Travel Company, Inc. McCabe World Travel, Inc. Lux Travel Consultants ILTM Largay Travel Paul Klein Travel Montecito Village Travel MTA - Mobile Travel Agents Lozano Travel de Mexico, S.A. de C.V. Metropolitan Touring C.A. PrimeTour agencia de Viagens e Turismo Ltda Q Cruise + Travel Ovation Vacations Odyssey Travel - ORMOND BEACH Post Haste Travel Service, Inc Rudi Steele Travel, Inc. Sanders Travel Centre Renshaw Travel Ovation Travel & Cruise Planners Quintessentially Travel Sabra Travel Sevilla Sol Viajes S.A. de C.V. Royal Int'l Travel Service Inc Plenia Travel Group RACT Travel Simplexity Travel Management The Local Foreigner Strong Travel Services Posh Travel, Ltd. -

Fashion Design Merchandising Strands and Standards

STRANDS AND STANDARDS FASHION DESIGN MERCHANDISING Course Description The Fashion Merchandising course is an introductory class that teaches the concepts of entry- level business and fashion fundamentals. The following list of skill strands prepares the student in fashion merchandising in the fundamentals of basic fashion concepts and marketing terminology, fashion cycles, key components of the fashion industry shuc a s fashion designers, fashion capitals and fashion week, retail merchandise categories, fashion promotion including advertising and social media, and fashion careers. Student leadership and competitive events (FCCLA and/or DECA) may be an integral part of the course. Intended Grade Level 10-12 Units of Credit .50 Core Code 34.01.00.00.145 Concurrent Enrollment Core Code NA Prerequisite Fashion Design Studio Skill Certification Test Number 405 Test Weight 0.5 License Type CTE and/or Secondary Education 6-12 Required Endorsement(s) Endorsement 1 Family & Consumer Sciences Endorsement 2 Fashion/Textiles/Apparel ADA Compliant: April 2021 FASHION DESIGN MERCHANDISING STRAND 1 Students will recognize basic fashion concepts and terminology. Standard 1 Review fashion terms. (Fashion Design Studio Standard 1) Accessories, apparel, avant-garde, classic, composite, design detail, draped, fad, fashion, fashion cycle, fit, garment type, haute couture, ready to wear, silhouette, style, tailored, trend, wardrobe. Standard 2 Identify fashion products. • Goods – tangible items that are made, manufactured, or grown. They include apparel, textiles, accessories, and other fashion products. • Services – intangible things that people do, such as tasks performed for customers. They include tailoring, cosmetology services, and stylist. STRAND 2 Students will examine the basics of fashion marketing and associated careers. -

Less Than a Decade After Launching Her Own Label, Tory Burch C'88 Is

Less than a decade after launching her own label, Tory Burch C’88 is one of the most recognizable names in fashion. Through mentoring and microloans, the Tory Burch Foundation is empowering other women entrepreneurs to follow in her footsteps. By Kathryn Levy Feldman From Brand to RoleModel a recent evening at Tory Burch LLC in downtown Manhattan, the resort collection of bright, classic, ON and preppy-chic clothing and accessories was not getting much attention from the 75 women gathered in the trademark orange-and-green showroom. In fact, the clothing racks had been pushed to the sides of the mirrored space to make way for 11 glass-topped tables, where the women—aged 20 to 60, and each the owner of her own small business—were engaged in a networking forum modeled on speed dating and organized by the Tory Burch Foundation and its micro-financing partner, Accion. The evening was one of about a dozen similar mentoring events Burch’s foundation has held in locations such as New York, Chicago, and Hawaii. Every 20 minutes, the women moved from table to table to tap the expertise of a different mentor in fields including (that evening) retail, hospitality, real estate, insurance, and marketing. Burch herself circulated among the tables, listening in on conversations and beaming. 44 NOV | DEC 2012 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE PHOTOGRAPH BY PATRICK DEMARCHELIER From Brand to “I’m lucky to have had many mentors throughout my career,” Burch says. THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE NOV | DEC 2012 45 “For our mentoring events, we focus Certainly she has demonstrated hers. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS About this Source Book 3 What is CLIA? 5 Facts about CLIA 7 Profile of the U.S. Cruise Industry 9 CLIA Leadership & Committees 11 Other North American Cruise Industry Associations • Florida-Caribbean Cruise Association 13 • North West CruiseShip Association 15 • Alaska Cruise Association 17 Roster of CLIA Member Lines 19 Profiles of CLIA Member Lines 21 CLIA Fleet by Member Line (as of January 1, 2011) 71 CLIA Fleet by Ship (as of January 1, 2011) 77 1 2 ABOUT THIS SOURCE BOOK The Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA) is pleased to present this guide as a reference tool for journalists and professional researchers. The 2011 Cruise Industry Source Book profiles CLIA’s 25 member cruise lines and contains general information about CLIA, its history and purpose. Each cruise line profile features the names of company principals and spokespersons, with phone numbers and e-mail addresses. Also included are descriptions of each line’s history and philosophy, as well as the destinations served by each company. The Source Book lists CLIA member-line ships in two ways: by individual company and by ship. In addition, it provides the names and phone numbers of key contacts at the other North American cruise industry associations – the Florida-Caribbean Cruise Association, the North West CruiseShip Association and the Alaska Cruise Association. The information contained in this guide was provided by the cruise lines and the associations. We welcome your feedback and appreciate hearing your comments. If you need additional information on CLIA, please contact Lanie Fagan, CLIA’s director of communications, at (754) 224-2202 or [email protected].