Runway Safety Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOPLIN REGIONAL AIRPORT February 2021 Essential Air Service Bid Comparison

JOPLIN REGIONAL AIRPORT February 2021 Essential Air Service Bid Comparison FEBRUARY 2021 JOPLIN 2020 EAS BID CONTEXT ▪ American Airlines had provided air service at Joplin since 2011; - Service was supported by the EAS program until March of 2019, when American saw no further need for subsidy - American traffic grew 76% from 2011 (54,146 passengers) to 2019 (95,148 passengers) - American placed dual class 76-seat RJs in the market beginning in 2017 - American and Joplin executed a separate MRG agreement to facilitate Chicago ORD service as of June of 2019. ▪ The Covid-19 pandemic caused the suspension of ORD service in March of 2020. American filed notice of intent to terminate all Joplin service on 8/28/2020, which triggered Joplin’s reentry into the EAS program. ▪ On 9/24/2020 the DOT issued Order 2020-9-23, holding American to provide basic EAS service at Joplin until a EAS bid proceeding results in the selection of and placement of an EAS designated carrier at Joplin. The Hold-in Order has now been extended to March 1, 2021 1, 2021. ▪ Order 2020-9-23 also called for carrier proposals to provide EAS service at Joplin, with or without subsidy, with proposals due on 10/26/2020. ▪ EAS proposals were received from three airlines, American, Boutique and SkyWest (United) and the DOT requested community comments on the three proposals by November 30, 2020. ▪ Joplin submitted the recommendation of SkyWest bid to DOT on November 23, 2020. 22 COMPARISON OF EAS PROPOSAL METRICS • American Airlines has submitted a proposal to provide Joplin air service, with subsidy • American Airlines proposed service to DFW hub, with annual subsidy of $1,528,913 for 12 round trips per week with 50-seat ERJ aircraft. -

Clovis Municipal Airport

Clovis Municipal Airport BAirportigBear MasterCityAi Planrport Master Plan Planning Services BigBearCityAirport Master Plan Planning Services Prepared by: In association with AIRPORT MASTER PLAN for Clovis Municipal Airport Clovis, New Mexico Prepared for City of Clovis, New Mexico by KSA, Inc. in association with CDM Smith, Inc. DRAFT FINAL September 2015 The preparation of this document was financially support, in part, through a grant provided by the New Mexico Department of Transportation. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the NMDOT or Federal Aviation Administration. Acceptance of this report by the NMDOT or FAA does not in any way constitute a commitment on the part of the State of New Mexico or United States to participate in any development depicted therein nor does it indicate that the proposed development is environmentally acceptable or would have justification in accordance with appropriate public laws. PLAN Table of Contents Chapter One: Inventory of Existing Conditions 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Overview of the Airport .......................................................................... 1-2 1.2.1 CVN Location .................................................................................1-2 1.2.2 CVN Sponsor Management ..............................................................1-4 1.2.3 CVN History ....................................................................................1-5 -

Summary Appraisal Report

Appraisal Report of the Benchmark Fair Market Rental Values for the State of Hawaii County of Kauai Airports As of July 1, 2016 County of Kauai Airports APPRAISAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TRANSMITTAL LETTER TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 I. CERTIFICATION 3 II. LIMITING CONDITIONS AND ASSUMPTIONS 5 III. ASSIGNMENT AND SUMMARY 8 Purpose of Appraisal 8 Function of Report 8 Interest Appraised 9 Intended Use and User of the Report 9 Scope of Work 9 Definitions 10 Airport Rental Categories 11 Rental Conclusions 12 IV. ECONOMIC ANALYSIS (State and County of Kauai) 16 V. BENCHMARK PROPERTY TYPES FOR ALL HAWAII STATE AIRPORTS 19 A. Spaces and Areas in Buildings 19 B. Industrial Lands 20 C. Parking Stalls 20 D. Aircraft Storage (Tie Downs) 21 VI. ASSUMPTIONS FOR ALL HAWAII STATE AIRPORTS 22 A. Utilities 22 B. Special Conditions - Buildings 22 C. Special Conditions - Lands 22 VII. VALUATION METHODOLOGY FOR ALL HAWAII STATE AIRPORTS 24 A. Building Spaces and Areas within the Airport or Adjacent to the Airport 26 1. Retail Rental Market Considerations 27 2. Office Rental Market Considerations 27 3. Industrial Rental Market Considerations 28 4. Calculation of Benchmark Rental Values for Retail, Office, and Industrial Spaces at Small Airports 28 5. Calculation of Rental Values for T-Hangars 29 Hastings, Conboy & Associates, Ltd. Page 1 County of Kauai Airports APPRAISAL REPORT B. Undeveloped Lands 29 1. General 29 (a) Valuation of Improved Unpaved Industrial Land 30 (b) Calculation of Paving Cost Recovery 31 (c) Valuation of Unimproved Industrial Land 32 2. Estimating Fee Simple Land Value 32 3. -

+/- 167.45 Acres for SALE Route 47 & Wheeler Sugar Grove, Illinois

+/- 167.45 Acres FOR SALE Route 47 & Wheeler Sugar Grove, Illinois Ideal Business Park Location! • Approx. 2 Miles to new I-88 interchange scheduled for 2019 • Approx. 1 Mile to Rt 56/30 Bypass • Only 1 stoplight from Interstate access • Sewer and water adjacent • Planned Business Park/Corridor Commercial Dan Flanagan, ALC Managing Broker Phone: 630-388-8522 Fax: 630-443-1239 email: [email protected] http://www.flanaganland.com Flanagan Realty, LLC represents the seller in this transaction and will not be acting as a dual agent or representative of the buyer unless specifically stated in writing. The information contained herein is from sources considered reliable, but is not guaranteed and is subject to change without notice. Buyers are advised to independently verify all information and perform their own due diligence. This offering may be withdrawn or subject to a change in price or terms without advance notice. Seller reserves the right to reject any and all offers. +/- 167.45 Acres FOR SALE Route 47 & Wheeler Sugar Grove, Illinois 17 Reasons to Consider This Sugar Grove Property for Industrial Development: 1. Less than 1 mile to Rt 56/U.S. 30 bypass to I-88 eastbound. 2. Less than 1 mile to westbound Rt 56/U.S. 30 with no tolls. 3. Only one stoplight away from interstate access. 4. <2.25 miles to full I-88 interchange at Rt 47 planned for 2019. 5. < 1/4 mile from proposed 500,000 sq ft manufacturing facility. 6. Within 30 miles of I-39, I-80, I-55, I-90, I-294 and O’Hare. -

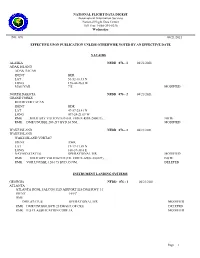

Page 1 NATIONAL FLIGHT DATA DIGEST Aeronautical Information

NATIONAL FLIGHT DATA DIGEST Aeronautical Information Services National Flight Data Center Toll Free 1-866-295-8236 Wednesday NO. 076 04/21/2021 EFFECTIVE UPON PUBLICATION UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED BY AN EFFECTIVE DATE NAVAIDS ALASKA NFDD 076 - 1 04/21/2021 ADAK ISLAND ADAK TACAN IDENT BER LAT 51-52-16.43 N LONG 176-40-26.8 W MAG VAR 7 E MODIFIED NORTH DAKOTA NFDD 076 - 2 04/21/2021 GRAND FORKS RED RIVER TACAN IDENT RDR LAT 47-57-25.41 N LONG 097-24-21.69 W RMK ....MILITARY VALIDATED (FIL FIDEX-RDR-200033).... NOTE RMK DME UNUSBL 209-219 BYD 30 NM. MODIFIED WAKE ISLAND NFDD 076 - 3 04/21/2021 WAKE ISLAND WAKE ISLAND VORTAC IDENT AWK LAT 19-17-11.69 N LONG 166-37-38.4 E NAVAID STATUS OPERATIONAL IFR MODIFIED RMK ....MILITARY VALIDATED (FIL FIDEX-AWK-200127).... NOTE RMK VOR UNUSBL 120-175 BYD 35 NM. DELETED INSTRUMENT LANDING SYSTEMS GEORGIA NFDD 076 - 1 04/21/2021 ATLANTA ATLANTA RGNL FALCON FLD AIRPORT ILS/DME RWY 31 IDENT I-FFC DME DME STATUS OPERATIONAL IFR MODIFIED RMK DME UNUSBL BYD 25 DEGS L OF CRS. DELETED RMK ILS CLASSIFICATION CODE IA. MODIFIED Page 1 AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL TOWERS MICHIGAN NFDD 076 - 1 04/21/2021 SAGINAW MBS INTL-ATCT IDENT MBS FREQUENCIES FREQUENCY 118.45 DELETED FREQUENCY USE ASR DELETED APCH/DEP CALL GREAT LAKES FREQUENCY 120.95 DELETED FREQUENCY USE APCH/S DEP/S DELETED AIRPORT ALASKA NFDD 076 - 1 04/21/2021 ATQASUK ATQASUK EDWARD BURNELL SR MEML AIRPORT ( ATK ) 50044.5A LATITUDE - 70-28-01.6 N LONGITUDE - 157-26-08.4 W RMK COLD TEMPERATURE RESTRICTED AIRPORT. -

Photo Courtesy of Travaasa Hana, Maui TM C

C Photo courtesy of Travaasa Hana, Maui TM C www.MokuleleAirlines.com A message from Ron Hansen, CEO of Mokulele Airlines What’s Inside? Not Even E komo mai! 6 Once Thank you for choosing Muralist Ken “East 3” Mokulele for your summer travel. It is our pleasure to have Nishimura teams up with you on board. the Hawaii Meth Project This is an exciting time for our to deliver an important airline. On July 1, we began message to kids offering daily service between Kalaeloa Airport on O‘ahu and Kahului Airport on Maui. Kalaeloa is located at the former Barber’s Point Naval Air Base John Rogers Field, and our grand opening and inaugural flight took Biggest Little place 15 years to the day that the former base was 10 Airshow closed. It was an historic occasion and we would like to extend our sincere appreciation to all who attended. Pacific Aviation Museum Pearl Harbor’s popular RC We’re also about to begin our renovations to our Kahului commuter terminal to make traveling to and event set to return bigger from this popular destination even more convenient and and better than ever comfortable for our passengers. This issue of Island Hopper has a strong emphasis on giving back to the community. You’ll learn about muralist Ken “East 3” Nishimura and his great work Recipe for with the Hawaii Meth Project to warn kids about the dangers of drugs. Our story on Chef Paul Onishi shows 14 Success how he helps at-risk kids turn their lives around through Chef Paul Onishi uses his dedication and determination. -

(Asos) Implementation Plan

AUTOMATED SURFACE OBSERVING SYSTEM (ASOS) IMPLEMENTATION PLAN VAISALA CEILOMETER - CL31 November 14, 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Weather Service / Office of Operational Systems/Observing Systems Branch National Weather Service / Office of Science and Technology/Development Branch Table of Contents Section Page Executive Summary............................................................................ iii 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................... 1 1.1 Background.......................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose................................................................................. 2 1.3 Scope.................................................................................... 2 1.4 Applicable Documents......................................................... 2 1.5 Points of Contact.................................................................. 4 2.0 Pre-Operational Implementation Activities ............................ 6 3.0 Operational Implementation Planning Activities ................... 6 3.1 Planning/Decision Activities ............................................... 7 3.2 Logistic Support Activities .................................................. 11 3.3 Configuration Management (CM) Activities....................... 12 3.4 Operational Support Activities ............................................ 12 4.0 Operational Implementation (OI) Activities ......................... -

Notice of Adjustments to Service Obligations

Served: May 12, 2020 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTINUATION OF CERTAIN AIR SERVICE PURSUANT TO PUBLIC LAW NO. 116-136 §§ 4005 AND 4114(b) Docket DOT-OST-2020-0037 NOTICE OF ADJUSTMENTS TO SERVICE OBLIGATIONS Summary By this notice, the U.S. Department of Transportation (the Department) announces an opportunity for incremental adjustments to service obligations under Order 2020-4-2, issued April 7, 2020, in light of ongoing challenges faced by U.S. airlines due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) public health emergency. With this notice as the initial step, the Department will use a systematic process to allow covered carriers1 to reduce the number of points they must serve as a proportion of their total service obligation, subject to certain restrictions explained below.2 Covered carriers must submit prioritized lists of points to which they wish to suspend service no later than 5:00 PM (EDT), May 18, 2020. DOT will adjudicate these requests simultaneously and publish its tentative decisions for public comment before finalizing the point exemptions. As explained further below, every community that was served by a covered carrier prior to March 1, 2020, will continue to receive service from at least one covered carrier. The exemption process in Order 2020-4-2 will continue to be available to air carriers to address other facts and circumstances. Background On March 27, 2020, the President signed the Coronavirus Aid, Recovery, and Economic Security Act (the CARES Act) into law. Sections 4005 and 4114(b) of the CARES Act authorize the Secretary to require, “to the extent reasonable and practicable,” an air carrier receiving financial assistance under the Act to maintain scheduled air transportation service as the Secretary deems necessary to ensure services to any point served by that air carrier before March 1, 2020. -

Ktebcharts.Pdf

AirNav: KTEB - Teterboro Airport http://www.airnav.com/airport/KTEB 1255 users online Teterboro Airport KTEB Teterboro, New Jersey, USA GOING TO TETERBORO? Loc | Ops | Rwys | IFR | FBO | Links FAA INFORMATION EFFECTIVE 22 AUGUST 2013 Com | Nav | Svcs | Stats | Notes Location FAA Identifier: TEB Lat/Long: 40-51-00.4000N / 074-03-39.0000W 40-51.006667N / 074-03.650000W 40.8501111 / -74.0608333 (estimated) Elevation: 8.4 ft. / 2.6 m (surveyed) Variation: 12W (1980) From city: 1 mile SW of TETERBORO, NJ Time zone: UTC -4 (UTC -5 during Standard Time) Zip code: 07608 Airport Operations Airport use: Open to the public Activation date: 01/1947 Sectional chart: NEW YORK Control tower: yes ARTCC: NEW YORK CENTER FSS: MILLVILLE FLIGHT SERVICE STATION NOTAMs facility: TEB (NOTAM-D service available) Attendance: CONTINUOUS Pattern altitude: TPA 1500' MSL FOR LARGE/TURBINE ACFT; 1000' MSL FOR ALL OTHERS. Wind indicator: lighted Segmented circle: no Lights: SS-SR Beacon: white-green (lighted land airport) AIRPORT BEACON OBSCURED W SIDE. Operates sunset to sunrise. Landing fee: yes Fire and rescue: ARFF index A Airline operations: ARFF INDEX B EQUIPMENT COVERAGE PRVDD. Road maps at: MapQuest Bing International operations: customs landing rights airport Google Yahoo! Airport Communications Aerial photo WARNING: Photo may not be TETERBORO GROUND: 121.9 current or correct TETERBORO TOWER: 119.5 125.1 NEW YORK APPROACH: 127.6 NEW YORK DEPARTURE: 126.7 119.2 CLEARANCE DELIVERY: 128.05 D-ATIS: 114.2 132.85 EMERG: 121.5 243.0 VFR-ADV: 119.5 WX AWOS-3 at JRB (9 nm S): 128.175 (212-425-1534) WX ASOS at LGA (10 nm SE): PHONE 718-672-6317 Photo courtesy of WX ASOS at CDW (10 nm W): PHONE 973-575-4417 StephenTaylorPhoto.com Photo taken 08-Sep-2013 WX AWOS-3 at LDJ (16 nm SW): 124.025 (908-862-7383) looking southwest. -

Acceptance Criteria of Airfield Concrete Pavement Using Seismic and Maturity Concepts

An IPRF Research Report Innovative Pavement Research Foundation Airport Concrete Pavement Technology Program Report IPRF-01-G-002-02-2 Acceptance Criteria of Airfield Concrete Pavement Using Seismic and Maturity Concepts Programs Management Office 5420 Old Orchard Road Skokie, IL 60077 May, 2006 An IPRF Research Report Innovative Pavement Research Foundation Airport Concrete Pavement Technology Program Report IPRF-01-G-002-02-2 Acceptance Criteria of Airfield Concrete Pavement Using Seismic and Maturity Concepts Principal Investigator Soheil Nazarian, PhD, PE Contributing Authors Deren Yuan, PhD Kurt Smith, PE Farhad Ansari, PhD Carlos Gonzalez, PE Programs Management Office 5420 Old Orchard Road Skokie, IL 60077 May, 2006 This report has been prepared by the Innovative Pavement Research Foundation under the Airport Concrete Pavement Technology Program. Funding is provided by the Federal Aviation Administration under Cooperative Agreement Number 01-G-002. Dr. Satish Agrawal is the Manager of the FAA Airport Technology R&D Branch and the Technical Manager of the Cooperative Agreement. Mr. Jim Lafrenz, P.E. is the Program Director for the IPRF. The Innovative Pavement Research Foundation and the Federal Aviation Administration thanks the Technical Panel that willingly gave of their expertise and time for the development of this report. They were responsible for the oversight and the technical direction. The names of those individuals on the Technical Panel follow. Mr. Jeff Rapol Federal Aviation Administration Dr. Kevin MacDonald, P.E. Cemstone Products Mr. Robert Taylor American Concrete Pavement Association Dr. Wayne Seiler, P.E. All About Pavements, Inc. Ms. Susan Winslow, P.E. Delta Airport Consultants, Inc. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented within. -

CSRA REGIONAL PLAN 2035 Regional Assessment Stakeholder Involvement Program

CSRA REGIONAL PLAN 2035 Regional Assessment Stakeholder Involvement Program CSRA Regional Plan 2035 Table of Contents A. Regional Assessment 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….…..4 2. Potential Regional Issues and Opportunities………………………………………………..……….8 2.1 Population…….……………………………………………………………………………….....8 2.2 Housing…………………………………………………………………………………………...9 2.3 Economic Development………………………………………………………………….……9 2.4 Land Use………………………………………………………………………………………..10 2.5 Transportation and Community Facilities……………………………………………….11 2.6 Natural and Environmental Resources……………………………………………………12 2.7 Intergovernmental Coordination…………………………………………………………..12 3. Regional Development Patterns………………………………………………………………………14 3.1 Projected Development Patterns…………………………………………………………..15 3.2 Analysis…………………………………………………………………………………………17 3.3 Areas Requiring Special Attention………………………………………………………...17 4. Supporting Data………………………………………………………………………………………….21 4.1 Population………………………………………………………………………………………21 4.2 Housing………………………………………………………………………………………....25 4.3 Economic Development………………………………………………………………………27 4.4 Land Use………………………………………………………………………………………...50 4.5 Transportation and Community Facilities………………………………………………..52 4.6 Natural and Environmental Resources……………………………………………………58 B. Stakeholder Involvement Program………………………………………..…………………………74 C. Regional Agenda (pending) Appendix: Analysis of Quality Community Objectives……………………………………………..79 Regional Assessment and Stakeholder Involvement Program | CSRA Regional Commission | 1 CSRA Regional Plan -

May 7,2009 Be Available in the Near Future at Http

Monlo no De porlme nf of lronsoo rt oii on Jim Lvnch, Dîrector *ruhrylaùtlthNde 2701 Prospect Avenue Brîon Schweífzer, Gov ernor PO Box 201001 Heleno MT 59620-1001 May 7,2009 Ted Mathis Gallatin Field 850 Gallatin Field Road #6 Belgrade MT 59714 Subject: Montana Aimorts Economic knpact Study 2009 Montana State Aviation System Plan Dear Ted, I am pleased to announce that the Economic Impact Study of Montana Airports has been completed. This study was a two-year collaborative eflort between the Montana Department of Transportation (MDT) Aeronautics Division, the Federal Aviation Administration, Wilbur Smith and Associates and Morrison Maierle Inc. The enclosed study is an effort to break down aviation's significant contributions in Montana and show how these impacts affect economies on a statewide and local level. Depending on your location, you may also find enclosed several copies of an individual economic summary specific to your airport. Results ofthe study clearly show that Montana's 120 public use airports are a major catalyst to our economy. Montana enplanes over 1.5 million prissengers per year at our 15 commercial service airports, half of whom are visiting tourists. The economic value of aviation is over $1.56 billion and contributes nearly 4.5 percent to our total gross state product. There arc 18,759 aviation dependent positions in Montana, accounting for four percent of the total workforce and $600 million in wages. In addition to the economic benefits, the study also highlights how Montana residents increasingly depend on aviation to support their healtþ welfare, and safety. Montana airports support critical services for medical care, agriculture, recreation, emergency access, law enforcement, and fire fighting.