Berio's Words on Music Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ut Contemporary Music Festival

UT CONTEMPORARY MUSIC FESTIVAL UT CONTEMPORARY MUSIC FESTIVAL WEDNESDAY, MARCH 4 MORNING PRESENTATIONS 9 a.m. HMC 244 Aaron Hunt - 9:05 - 9:25 a.m. "Rhythmic Hypnosis: A Theory of Rhythm and Meter in the Music of Tool" Fabio Fabbri - 9:30 - 10:05 a.m. "Techniques and Terminology for the Analysis of Electroacoustic Music and More" Ian Evans Guthrie - 10:10 - 10:30 a.m. “Rhythm as a Function" Robert Strobel - 10:35 a.m. - 11 a.m. "The Dangers of Excessive Conceptuality in Theory and Composition" EMILY KOH AND TRAVIS ALFORD PRESENTATIONS 2 - 4 p.m. HMC 110 CONCERT ONE 6 - 7:30 p.m. Sandra G. Powell Recital Hall The Outside Mark Engebretson Mark Engebretson, alto saxophone postcards Chin Ting Chan Yu-Fang Chen, violin Finding the Right Words Aaron Hunt Vicki Leona, percussion UT CONTEMPORARY MUSIC FESTIVAL Lemoncholy Gabriel Brady Gabriel Brady, piano LIGO Alissa Voth Bethany Padgett, flute Kae So Wae Train Vicki Leona Turner McCabbe and Vicki Leona, percussion Cullen Burke, Aaron Hunt, and Claire Terrell, perspectives (voice) one final gyre Alex Burtzos Allison Adams and Corey Martin, saxophone THURSDAY, MARCH 5 CONCERT TWO 11 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. Sandra G. Powell Recital Hall A Farewell Elegy Ian Evans Guthrie Ian Evans Guthrie, piano Breathe Slow, Breathe Deep Ed Martin Jeri-Mae G. Astolfi, piano Ctrl C Adam Stanovic fixed media Isaac's World Filipe Leitao fixed media Missing Memories John Baxter John Baxter, piano UT CONTEMPORARY MUSIC FESTIVAL London 2012 Hunter Prueger Hunter Prueger , alto saxophone Confab Andrew Hannon Joseph Brown, trombone RITA D'ARCANGELO FLUTE MASTERCLASS 12:40 - 1:55 p.m. -

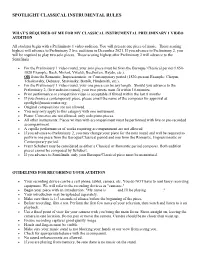

Spotlight Classical Instrumental Rules

SPOTLIGHT CLASSICAL INSTRUMENTAL RULES WHAT’S REQUIRED OF ME FOR MY CLASSICAL INSTRUMENTAL PRELIMINARY 1 VIDEO AUDITION All students begin with a Preliminary 1 video audition. You will present one piece of music. Those scoring highest will advance to Preliminary 2 live auditions in December 2021. If you advance to Preliminary 2, you will be required to play two solo pieces. Those scoring highest after Preliminary 2 will advance to the Semifinals • For the Preliminary 1 video round, your solo piece must be from the Baroque/ Classical period (1650- 1820 Example: Bach, Mozart, Vivaldi, Beethoven, Haydn, etc.). OR from the Romantic, Impressionistic, or Contemporary period (1820-present Example: Chopin, Tchaikovsky, Debussy, Stravinsky, Bartók, Hindemith, etc.). • For the Preliminary 1 video round, your one piece can be any length. Should you advance to the Preliminary 2, (live audition round), your two pieces must fit within 10-minutes. • Prior performance or competition video is acceptable if filmed within the last 8 months • If you choose a contemporary piece, please email the name of the composer for approval at [email protected]. • Original compositions are not allowed. • You may only apply to this category with one instrument. • Piano: Concertos are not allowed; only solo piano pieces. • All other instruments: Pieces written with accompaniment must be performed with live or pre-recorded accompaniment. • A capella performances of works requiring accompaniment are not allowed. • If you advance to Preliminary 2, you may change your piece for the next round and will be required to perform one piece from the Baroque/Classical period and one from the Romantic, Impressionistic or Contemporary period. -

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio's

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia Richard Lee-Thai 30024611 MUSI 333: Late Romantic and Modern Music Dr. Freidemann Sallis Due Date: Friday, April 6th 1 | P a g e Luciano Berio (1925-2003) is an Italian composer whose works have explored serialism, extended vocal and instrumental techniques, electronic compositions, and quotation music. It is this latter aspect of quotation music that forms the focus of this essay. To illustrate how Berio approaches using musical and literary quotations, the third movement of Berio’s Sinfonia will be the central piece analyzed in this essay. However, it is first necessary to discuss notable developments in Berio’s compositional style that led up to the premiere of Sinfonia in 1968. Berio’s earliest explorations into musical quotation come from his studies at the Milan Conservatory which began in 1945. In particular, he composed a Petite Suite for piano in 1947, which demonstrates an active imitation of a range of styles, including Maurice Ravel, Sergei Prokofiev and the neoclassical language of an older generation of Italian composers.1 Berio also came to grips with the serial techniques of the Second Viennese School through studying with Luigi Dallapiccola at the Tanglewood Music Festival in 1952 and analyzing his music.2 The result was an ambivalence towards the restrictive rules of serial orthodoxy. Berio’s approach was to establish a reservoir of pre-compositional resources through pitch-series and then letting his imagination guide his compositional process, whether that means transgressing or observing his pre-compositional resources. This illustrates the importance that Berio’s places on personal creativity and self-expression guiding the creation of music. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Conrad Schnitzler / Pole Con-Struct

CONRAD SCHNITZLER / POLE CON-STRUCT CD / LP (+ CD) / Digital March 24th 2017 Who is Conrad Schnitzler? Conrad Schnitzler (1937–2011), composer and concept artist, is one of the most important representatives of Germany’s electronic music avant-garde. A student of Joseph Beuys, he founded Berlin’s legendary Zodiak Free Arts Lab, a subculture club, in 1967/68, was a member of Tangerine Dream (together with Klaus Schulze and Edgar Froese) and Kluster (with Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius) and also released countless solo albums. Who is Pole? The Düsseldorf-native musician, producer, remixer and mastering engineer Stefan Betke looks back on a steady two decade career in abstract electronic club music. Together with Barbara Preisinger he created the label „scape Records” and his own mastering studio „scape-mastering”. What is the concept of the Con-Struct series? Conrad Schnitzler liked to embark on daily excursions through the sonic diversity of his synthesizers. Finding exceptional sounds with great regularity, he preserved them for use in combination with each other in subsequent live performances. He thus amassed a vast sound archive of his discoveries over time. When Jens Strüver, the producer of the Con-Struct series, was granted access to this audio library at the outset of the 2010 decade, he came up with the idea of con-structing new compositions, not remixes, from the archived material. On completion of the first Con-Struct album, he decided to develop the concept into a series, with different electronic musicians invited into Schnitzler’s unique world of sound. A few words from Pole on his con-structions To be honest, in earlier times I never quite warmed to Conrad Schnitzler's work. -

A Method for the Transcription and Analysis of Electroacoustic Music

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2014 Emerging Musical Structures: A method for the transcription and analysis of Electroacoustic Music Mario Mazzoli Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/71 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EMERGING MUSICAL STRUCTURES: A METHOD FOR THE TRANSCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS OF ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC. by MARIO MAZZOLI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii © 2014 MARIO MAZZOLI All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________ _________________________ Date Professor Jeff Nichols Chair of Examining Committee ________________ _________________________ Date Professor Norman Carey Executive Officer Distinguished Professor Joseph N. Straus Professor Mark Anson-Cartwright Professor David Olan Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract EMERGING MUSICAL STRUCTURES: A METHOD FOR THE TRANSCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS OF ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC. by MARIO MAZZOLI Advisor: Distinguished Professor Joseph N. Straus This dissertation proposes a method for transcribing “electroacoustic” music, and subsequently a number of methods for its analysis, utilizing the transcription as main ground for investigation. -

Invenzione Festival Berio

INVENZIONE FESTIVAL BERIO Du 2 au 20 décembre 2013 www.cnsmd-lyon.fr , Paris DES SIGNES DES : conception graphique conception Invenzione festival Berio du 2 au 20 décembre 2013 La musique n’est pas pressée : elle vit dans notre culture, le temps des arbres et des forêts, de la mer et des grandes villes. Luciano Berio Luciano Berio (1925-2003) Luciano Berio a marqué pour toujours la musique de la seconde moitié du XXe siècle. Son œuvre, sans frontières et d’une incroyable diversité, a mis à profit toutes les techniques, du sérialisme à l’électroacoustique. L’homme ne s’est laissé enfermer dans aucun clan, parti pris théorique ou gratuité abstraite. Son intelligence prend appui sur la vie, un esprit d’invention et une imagination généreuse. Il réinventa les continuités en gardant une curiosité insatiable pour les expériences exploratoires. Ses dialogues avec littérature, linguistique, anthropologie ou ethnomusicologie ont nourri son inventivité et c’est en tant que compositeur qu’il s’est approprié les matières qui le fascinaient afin d’en extraire des effets parfois fort éloignés de leur contexte d’origine. Berio a aussi sondé des domaines originaux et longtemps oubliés de notre culture occidentale, en particulier celui de la voix féminine qui a pris de plus en plus de place dans ses œuvres ; le chant impliquant un texte, Berio a collaboré avec des poètes tels que Sanguineti. Passionné par le potentiel des timbres instrumentaux, il a écrit une vaste série de pièces pour instruments solo, les fameuses Sequenza, puis s’est attaché dès les années 60 à explorer les plus improbables combinaisons de timbres. -

Vocality and Listening in Three Operas by Luciano Berio

Clare Brady Royal Holloway, University of London The Open Voice: Vocality and Listening in three operas by Luciano Berio Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2017 The Open Voice | 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Patricia Mary Clare Brady, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: February 1st 2017 The Open Voice | 2 Abstract The human voice has undergone a seismic reappraisal in recent years, within musicology, and across disciplinary boundaries in the humanities, arts and sciences; ‘voice studies’ offers a vast and proliferating array of seemingly divergent accounts of the voice and its capacities, qualities and functions, in short, of what the voice is. In this thesis, I propose a model of the ‘open voice’, after the aesthetic theories of Umberto Eco’s seminal book ‘The Open Work’ of 1962, as a conceptual framework in which to make an account of the voice’s inherent multivalency and resistance to a singular reductive definition, and to propose the voice as a site of encounter and meaning construction between vocalist and receiver. Taking the concept of the ‘open voice’ as a starting point, I examine how the human voice is staged in three vocal works by composer Luciano Berio, and how the voice is diffracted through the musical structures of these works to display a multitude of different, and at times paradoxical forms and functions. In Passaggio (1963) I trace how the open voice invokes the hegemonic voice of a civic or political mass in counterpoint with the particularity and frailty of a sounding individual human body. -

Music-Program-Sheet.Pdf

MUSIC TECHNOLOGY Music Technology Associate in Science Major Code 2206 Program Description Entrance Requirements The Associate in Science degree in Music Technology is HS Diploma or GED designed for students who intend to seek employment in the commercial music field and for those who are presently Music Student Advising employed in the music technology field and desire Prior to seeking general academic advisement on their home advancement. Some of the careers, to which this sequence campuses, AA students majoring in music, and AS students may lead, are recording engineer, sound designer, live sound majoring in music production must first seek advisement reinforcement engineer and producer. on the music course of study through the office of the Visual & Performing Arts Department on Central Campus (Building Related Programs 4, Room 130). Auditions for performance and registration for Audio Technology Certificate Major Code 6309 music courses will be handled in the V&PA offices only. Broward College is accredited by the National Association of Vocal Studies Students Language Requirement Schools of Music (NASM), 11250 Roger Bacon Drive, Suite All Broward College music students who are majoring in vocal 21 Reston, VA 20190-5248. Telephone: 703-437-0700, E- studies MUST as a required part of their studies take one of the following languages: French, German and/or mail: [email protected] Italian. Courses in these languages are available through the communications department at Broward College. First Year, Term I Second Year, Term I MUS1360 -

Music (MUSIC) 1

Music (MUSIC) 1 Music (MUSIC) Courses MUSIC 103. Music Technology Tools. 1 Credit. An introduction to music software and technology commonly used by musicians. P: conc enr Music 151 Fall Only. MUSIC 115. Ear Training and Sight Singing I. 1 Credit. Concentrated drill in all aspects of musicianship. Emphasis on sight singing and aural perception in intervals, melodies, chords and rhythms. Fall Only. MUSIC 116. Ear Training and Sight Singing II. 1 Credit. Concentrated drill in all aspects of musicianship. Emphasis on sight singing and aural perception in intervals, melodies, chords and rhythms. P: MUSIC 115 Spring. MUSIC 120. Video Game Music. 3 Credits. This course will equip students to understand the interdisciplinary role, historical progression, musical methodology, technological application, and unique artistry of music in video games. Students will contribute to the class learning environment by researching and presenting a game music composer from an interdisciplinary perspective. Through guided instruction, students will also compose their own basic game music. (No musical background required!) Spring. MUSIC 121. Survey of Western Music. 3 Credits. The musical styles of several well-known composers as evident in selected compositions; review of a basic repertoire of musical compositions of various forms and styles. Fall Only. MUSIC 122. Electronic Music Production. 3 Credits. This project-based course will teach the basic principles of modern music production using the Ableton Live software platform. Topics covered include audio and MIDI tracking, clip editing, software instruments, effects, synthesis, sampling, and elementary editing and mixing. Fall and Spring. MUSIC 151. Music Theory I. 3 Credits. The materials of which Western music is made are viewed not only in structural terms, but also in psychological, aesthetic and social perspective. -

Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(S): Miguel A

Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(s): Miguel A. Roig-Francolí Source: Indiana Theory Review, Vol. 33, No. 1-2 (Summer 2017), pp. 36-68 Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.02 Accessed: 03-09-2018 01:27 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press, Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Theory Review This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Mon, 03 Sep 2018 01:27:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First-Century Students Miguel A. Roig-Francolí University of Cincinnati ost-tonal music has a pr problem among young musicians, and many not-so-young ones. Anyone who has recently taught a course on the theory and analysis of post-tonal music to a general Pmusic student population mostly made up of performers, be it at the undergraduate or master’s level, will probably immediately understand what the title of this article refers to. -

Fylkingen's Text-Sound Festivals 1968–1974

Fylkingen’s Text-Sound Festivals 1968–1974 Teddy Hultberg Abstract In the 1960s the concept and the genre of “text-sound composition” were born in Sweden. Being an offspring of sound poetry in various forms and of the new electro- acoustic music of the post-war years, it took shape as an intermedia art form par excel- lence. This essay traces the emergence of text-sound in a Swedish context and especially its appearance at the internationally renowned text-sound festivals held at Fylkingen in Stockholm during the years 1968–1974. By the time the term was invented in the 1960, text-sound composition, as an aesthetic practice, was already an international phenomenon. The Swedish version of this intermedia genre was given an international plat- form through the famous text-sound festivals that were organised by Fylkingen in Stockholm between 1968 and 1974. Founded as a chamber music society in 1933, Fylkingen had at this time developed into an organisa- tion that promoted all the new events in music, dance and theatre. And in this context sound poetry and text-sound composition appeared to be typi- cal art forms of the time – art forms that would explore the interstices between word and sound, poetry and music, and which would further the investigation of the electro-acoustic landscape staked out in avant-garde music from the post-war period by composers such as Pierre Schaeffer, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Luciano Berio. In short, the history of text-sound composition can be seen as the history of how technology during the early 1960s changed the poetic expression when it opened the literary field to a new kind of sound poetry.