Navigating the Crisis in Local and Regional News: a Critical Review of Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Journalism Matters a Media Standards Trust Series

Why Journalism Matters A Media Standards Trust series Lionel Barber, editor of the Financial Times The British Academy, Wednesday 15 th July These are the best of times and the worst of times if you happen to be a journalist, especially if you are a business journalist. The best, because our profession has a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to report, analyse and comment on the most serious financial crisis since the Great Crash of 1929. The worst of times, because the news business is suffering from the cyclical shock of a deep recession and the structural change driven by the internet revolution. This twin shock has led to a loss of nerve in some quarters, particularly in the newspaper industry. Last week, during a trip to Colorado and Silicon Valley, I was peppered with questions about the health of the Financial Times . The FT was in the pink, I replied, to some surprise. A distinguished New York Times reporter remained unconvinced. “We’re all in the same boat,” he said,”but at least we’re all going down together.” My task tonight is not to preside over a wake, but to make the case for journalism, to explain why a free press and media have a vital role to play in an open democratic society. I would also like to offer some pointers for the future, highlighting the challenges facing what we now call the mainstream media and making some modest suggestions on how good journalism can not only survive but thrive in the digital age. Let me begin on a personal note. -

University Microfilms. a XER0K Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

72-11430 BRADEN, James Allen, 1941- THE LIBERALS AS A THIRD PARTY IN BRITISH POLITICS, 1926-1931: A STUDY IN POLITICAL COMMUNICATION. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 History, modern University Microfilms. A XER0K Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan (^Copyright by James Allen Braden 1971 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE LIBERALS AS A THIRD PARTY IN BRITISH POLITICS 1926-1931: A STUDY IN POLITICAL COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By James Allen Braden, B. S., M. A. * + * * The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by ment of History PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages haveIndistinct print. Filmed asreceived. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS Sir, in Cambria are we born, and gentlemen: Further to boast were neither true nor modest, Unless I add we are honest. Belarius in Cymbeline. Act V, sc. v. PREFACE In 1927 Lloyd George became the recognized leader of the Liberal party with the stated aim of making it over into a viable third party. Time and again he averred that the Liberal mission was to hold the balance— as had Parnell's Irish Nationalists— between the two major parties in Parlia ment. Thus viewed in these terms the Liberal revival of the late 1920's must be accounted a success for at no time did the Liberals expect to supplant the Labour party as the party of the left. The subtitle reads: "A Study in Political Communi cation " because communications theory provided the starting point for this study. But communications theory is not im posed in any arbitrary fashion, for Lloyd George and his fol lowers were obsessed with exploiting modern methods of commu nications. -

Newspaper Distribution List

Newspaper Distribution List The following is a list of the key newspaper distribution points covering our Integrated Media Pro and Mass Media Visibility distribution package. Abbeville Herald Little Elm Journal Abbeville Meridional Little Falls Evening Times Aberdeen Times Littleton Courier Abilene Reflector Chronicle Littleton Observer Abilene Reporter News Livermore Independent Abingdon Argus-Sentinel Livingston County Daily Press & Argus Abington Mariner Livingston Parish News Ackley World Journal Livonia Observer Action Detroit Llano County Journal Acton Beacon Llano News Ada Herald Lock Haven Express Adair News Locust Weekly Post Adair Progress Lodi News Sentinel Adams County Free Press Logan Banner Adams County Record Logan Daily News Addison County Independent Logan Herald Journal Adelante Valle Logan Herald-Observer Adirondack Daily Enterprise Logan Republican Adrian Daily Telegram London Sentinel Echo Adrian Journal Lone Peak Lookout Advance of Bucks County Lone Tree Reporter Advance Yeoman Long Island Business News Advertiser News Long Island Press African American News and Issues Long Prairie Leader Afton Star Enterprise Longmont Daily Times Call Ahora News Reno Longview News Journal Ahwatukee Foothills News Lonoke Democrat Aiken Standard Loomis News Aim Jefferson Lorain Morning Journal Aim Sussex County Los Alamos Monitor Ajo Copper News Los Altos Town Crier Akron Beacon Journal Los Angeles Business Journal Akron Bugle Los Angeles Downtown News Akron News Reporter Los Angeles Loyolan Page | 1 Al Dia de Dallas Los Angeles Times -

Monopoly, Power and Politics in Fleet Street: the Controversial Birth of IPC Magazines, 1958-63

Monopoly, Power and Politics in Fleet Street: The Controversial Birth of IPC Magazines, 1958-63 Howard Cox and Simon Mowatt Britain’s newspaper and magazine publishing business did not fare particularly well during the 1950s. With leading newspaper proprietors placing their desire for political influence above that of financial performance, and with working practices in Fleet Street becoming virtually ungovernable, it was little surprise to find many leading periodical publishers on the verge of bankruptcy by the decade’s end. A notable exception to this general picture of financial mismanagement was provided by the chain of enterprises controlled by Roy Thomson. Having first established a base in Scotland in 1953 through the acquisition of the Scotsman newspaper publishing group, the Canadian entrepreneur brought a new commercial attitude and business strategy to bear on Britain’s periodical publishing industry. Using profits generated by a string of successful media activities, in 1959 Thomson bought a place in Fleet Street through the acquisition of Lord Kemsley’s chain of newspapers, which included the prestigious Sunday Times. Early in 1961 Thomson came to an agreement with Christopher Chancellor, the recently appointed chief executive of Odhams Press, to merge their two publishing groups and thereby create a major new force in the British newspaper and magazine publishing industry. The deal was never consummated however. Within days of publicly announcing the merger, Odhams found its shareholders being seduced by an improved offer from Cecil King, Chairman of Daily Mirror Newspapers, Ltd., which they duly accepted. The Mirror’s acquisition of Odhams was deeply controversial, mainly because it brought under common ownership the two left-leaning British popular newspapers, the Mirror and the Herald. -

Great Britain Newspaper Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8d224gm No online items Inventory of the Great Britain newspaper collection Hoover Institution Archives Staff Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2019 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: https://www.hoover.org/library-archives Inventory of the Great Britain 2019C144 1 newspaper collection Title: Great Britain newspaper collection Date (inclusive): 1856-2001 Collection Number: 2019C144 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: In English, Estonian, Danish, Dutch, Norwegian, German, French and Greek. Physical Description: 452 oversize boxes(686.7 Linear Feet) Abstract: The newspapers in this collection were originally collected by the Hoover Institution Library and transferred to the Archives in 2019. The Great Britain newspaper collection (1856-2001) comprises ninety-seven different titles of publication in English, Estonian, Danish, Dutch, Norwegian, German, French, and Greek. All titles within this collection have been further analyzed in Stanford University Libraries catalog. Hoover Institution Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights Due to the assembled nature of this collection, copyright status varies across its scope. Copyright is assumed to be held by the original newspaper publications, which should be contacted wherein public domain has not yet passed. The Hoover Institution can neither grant nor deny permission to publish or reproduce materials from this collection. Acquisition Information Materials were acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 2019 from the Hoover Institution Library. Preferred Citation The following information is suggested along with your citation: [Title/Date of Publication], Great Britain newspaper collection [Box no.], Hoover Institution Archives. -

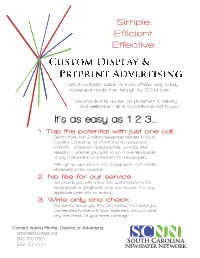

It's As Easy As 1-2-3

Simple. Efficient. Effective. There is no faster, easier, or more efficient way to buy newspaper media than through the SCNN team. We provide rate quotes, ad placement & delivery, and verification - all at no additional cost to you. It’s as easy as 1-2-3... 1. Tap the potential with just one call Reach more than 2 million newspaper readers in South Carolina. Contact us for information on newspaper markets – circulation, demographics, ad rates and research – whether you want to run in one newspaper or any combination of more than 100 newspapers. Although we specialize in S.C. newspapers, out-of-state placement is also available. 2. No fee for our service We provide you with a free rate quote tailored to the newspapers or geographic area you request. You pay applicable rates with no markup. 3. Write only one check Our service saves you time and money. We’ll send you one itemized invoice with your tearsheets and you write only one check for your entire campaign. Contact Alanna Ritchie, Director of Advertising: [email protected] 803.750.9561 South Carolina 888.727.7377 Newspaper Network S.C. Press Association Member Newspapers ABBEVILLE DORCHESTER MARION The Press and Banner, Abbeville The Eagle-Record, St. George Marion County News Journal, Marion AIKEN The Summerville Journal Scene, Marion Star & Mullins Enterprise, Marion Aiken Standard, Aiken ■ Summerville MARLBORO The Star, North Augusta EDGEFIELD Marlboro Herald Advocate, Bennettsville ALLENDALE The Edgefi eld Advertiser, Edgefi eld MCCORMICK The Allendale Sun FAIRFIELD McCormick -

Crisis in Britain's Press

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY June 1, 1957 From the London End Crisis in Britain's Press THE dwindling number of resulted in the 'Herald's' deci ing revenue becomes increasing British provincial daily sion to choose the former in the ly dependent on the circulation newspapers, the persistent talk hope that circulation will in levels and the class of readers of rising costs and merges in crease but since its readers find which particular newspaper's Fleet Street, the particularly that they obtain more for their reach. For example, the famous high casualty rate among week money for this type of journal Hulton Survey of 1955 showed lies and now the impending ism in the 'Daily Mirror', the that 17.4 per cent of the 1.3 amalgamation of the two na 'Herald' is losing both types of million of "well-to-do" readers tional dailies—'News Chronicle' readers so that today it has a in the country bought the and the 'Daily Herald' brings to circulation of no more than 1½. 'Times'. The majority of this the open a crisis, which for some million compared to over 2¼ income group (53 per cent) years was, in terms of news, million in 1948. The circulation however read the less ponderous confined to the editorial rooms of the 'Chonicle' too has ten but starkly conservative 'Daily or the private meetings of ded to fall over the past 10 Mail' and 'Daily Telegraph'. The anxious boards of directors. The years. It is now being suggested "working class or the poor" crisis takes the broadest possi that the circulation of these group who represented 26,3 ble character. -

City Research Online

Hunter,, F.N. (1982). Grub Street and academia : the relationship between journalism and education, 1880-1940, with special reference to the London University Diploma for Journalism, 1919-1939. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) City Research Online Original citation: Hunter,, F.N. (1982). Grub Street and academia : the relationship between journalism and education, 1880-1940, with special reference to the London University Diploma for Journalism, 1919-1939. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/8229/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. Grub Street and Academia: The relationship between TOTIrnalism and education,' 1880-1940, with special reference to the London University Diploma for Journalism, 1919-1939. Frederic Newlands Hunter, M.A. -

Breaking News

BREAKING NEWS First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE canongate.co.uk This digital edition first published in 2018 by Canongate Books Copyright © Alan Rusbridger, 2018 The moral right of the author has been asserted British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library ISBN 978 1 78689 093 1 Export ISBN 978 1 78689 094 8 eISBN 978 1 78689 095 5 To Lindsay and Georgina who, between them, shared most of this journey Contents Introduction 1. Not Bowling Alone 2. More Than a Business 3. The New World 4. Editor 5. Shedding Power 6. Guardian . Unlimited 7. The Conversation 8. Global 9. Format Wars 10. Dog, Meet Dog 11. The Future Is Mutual 12. The Money Question 13. Bee Information 14. Creaking at the Seams 15. Crash 16. Phone Hacking 17. Let Us Pay? 18. Open and Shut 19. The Gatekeepers 20. Members? 21. The Trophy Newspaper 22. Do You Love Your Country? 23. Whirlwinds of Change Epilogue Timeline Bibliography Acknowledgements Also by Alan Rusbridger Notes Index Introduction By early 2017 the world had woken up to a problem that, with a mixture of impotence, incomprehension and dread, journalists had seen coming for some time. News – the thing that helped people understand their world; that oiled the wheels of society; that pollinated communities; that kept the powerful honest – news was broken. The problem had many different names and diagnoses. Some thought we were drowning in too much news; others feared we were in danger of becoming newsless. -

Capturing the Public Value of Heritage

Capturing the Public Value of Heritage THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE LONDON CONFERENCE 25–26 January 2006 Fig 1 In 1986 Stonehenge was among the first places in the UK to be inscribed as a World Heritage Site – in the language of UNESCO, a place of Outstanding Universal Value. Since then the future of this iconic monument, severed from its surrounding prehistoric landscape by two busy roads and serviced by an ugly and intrusive visitor centre, has been the subject of endless debate. Now, 20 years on, the concept of public value – what the public values – may at last be one of the keys to a better future for England’s most famous archaeological site. © English Heritage Capturing the Public Value of Heritage THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE LONDON CONFERENCE 25–26 January 2006 Edited by Kate Clark Acknowledgements The conference was organised jointly by Kate Clark (Heritage Lottery Fund), Frances MacLeod (Department for Culture, Media and Sport), Duncan McCallum (English Heritage) and Tony Burton (National Trust). The event was managed by Jane Callaghan and her team from Multimedia Ventures and was held at the Royal Geographical Society in London. We owe a real debt of gratitude to Jane and her team, and to the staff of the RGS for making the event such a success. We would like to thank each of the speakers and in particular our guests – David Throsby from Australia, Christina Cameron from Canada and Randall Mason from the USA. Special thanks also go to the members of the Citizens' Juries – Bunney Hayes, Dolly Tank, Michael Rosser and Leila Seton. -

The Future of Investigative Journalism

HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on Communications 3rd Report of Session 2010–12 The future of investigative journalism Report Ordered to be printed 31 January 2012 and published 16 February 2012 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords London : The Stationery Office Limited £14.50 HL Paper 256 The Select Committee on Communications The Select Committee on Communications was appointed by the House of Lords on 22 June 2010 with the orders of reference “to consider the media and the creative industries.” Current Membership Lord Bragg Lord Clement-Jones Baroness Deech Baroness Fookes Lord Gordon of Strathblane Lord Inglewood (Chairman) Lord Macdonald of Tradeston Bishop of Norwich Lord Razzall Lord St John of Bletso Earl of Selborne Lord Skelmersdale Declaration of Interests See Appendix 1. A full list of Members’ interests can be found in the Register of Lords’ Interests: http://www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/standards-and-interests/register-of-lords-interests Publications All publications of the Committee are available on the internet at: http://www.parliament.uk/hlcommunications Parliament Live Live coverage of debates and public sessions of the Committee’s meetings are available at: www.parliamentlive.tv General Information General Information about the House of Lords and its Committees, including guidance to witnesses, details of current inquiries and forthcoming meetings is on the internet at: http://www.parliament.uk/business/lords Committee Staff The current staff of the Committee are Anna Murphy (Clerk), Alan Morrison (Policy Analyst) and Rita Logan (Committee Assistant). Contact Details All correspondence should be addressed to the Clerk of the Select Committee on Communications, Committee Office, House of Lords, London SW1A 0PW. -

Proquest Dissertations

001214 UNION LIST OF NQN-CAiJADIAN NEWiiPAPLRJl HELD BY CANADIAN LIBRARIES - CATALOGUE CQLLECTIF DES JOURNAUX NQN-CANADIMS DANS LES BIBLIOTHEQUES DU CANADA by Stephan Rush Thesis presented to the Library School of the University of Ottawa as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Library Science :. smtiOTHlQUS 5 •LIBRARIES •%. ^/ty c* •o** Ottawa, Canada, 1966 UMI Number: EC55995 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC55995 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was prepared under the supervision of Dr» Gerhard K. Lomer, of the Library school of the Univ ersity of Ottawa. The writer Is indebted to Dr. W. Kaye Lamb, the National Librarian of Canada, and to Miss Martha Shepard, Chief of the Reference Division of the National Library, for their Interest and support in his project, to Dr. Ian C. Wees, and to Miss Flora E. iatterson for their sugges tions and advice, and to M. Jean-Paul Bourque for the translation of form letters from English into French, It was possible to carry out this project only because of Miss Martha Shepard1s personal letter to the Canadian libraries and of the wholehearted co-operation of librarians across Canada in filling out the question naires.