Irish Language As a Part of Cultural Identity of the Irish Anna Slatinská

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Counter-Aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing

Notes Chapter One Introduction: Taoibh Amuigh agus Faoi Ghlas: The Counter-aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing 1. Gerry Adams, “The Fire,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 37. 2. Ibid., 46. 3. Pat Magee, Gangsters or Guerillas? (Belfast: Beyond the Pale, 2001) v. 4. David Pierce, ed., Introduction, Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Reader (Cork: Cork University Press, 2000) xl. 5. Ibid. 6. Shiela Roberts, “South African Prison Literature,” Ariel 16.2 (Apr. 1985): 61. 7. Michel Foucault, “Power and Strategies,” Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980) 141–2. 8. In “The Eye of Power,” for instance, Foucault argues, “The tendency of Bentham’s thought [in designing prisons such as the famed Panopticon] is archaic in the importance it gives to the gaze.” In Power/ Knowledge 160. 9. Breyten Breytenbach, The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983) 147. 10. Ioan Davies, Writers in Prison (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 4. 11. Ibid. 12. William Wordsworth, “Preface to Lyrical Ballads,” The Norton Anthology of English Literature vol. 2A, 7th edition, ed. M. H. Abrams et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000) 250. 13. Gerry Adams, “Inside Story,” Republican News 16 Aug. 1975: 6. 14. Gerry Adams, “Cage Eleven,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 20. 15. Wordsworth, “Preface” 249. 16. Ibid., 250. 17. Ibid. 18. Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 27. 19. W. B. Yeats, Essays and Introductions (New York: Macmillan, 1961) 521–2. 20. Bobby Sands, One Day in My Life (Dublin and Cork: Mercier, 1983) 98. -

"Third Way" Republicanism in the Formation of the Irish Republic Kenneth Lee Shonk, Jr

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects "Irish Blood, English Heart": Gender, Modernity, and "Third Way" Republicanism in the Formation of the Irish Republic Kenneth Lee Shonk, Jr. Marquette University Recommended Citation Shonk, Jr., Kenneth Lee, ""Irish Blood, English Heart": Gender, Modernity, and "Third Way" Republicanism in the Formation of the Irish Republic" (2010). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 53. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/53 “IRISH BLOOD, ENGLISH HEART”: GENDER, MODERNITY, AND “THIRD-WAY” REPUBLICANISM IN THE FORMATION OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC By Kenneth L. Shonk, Jr., B.A., M.A., M.A.T. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2010 ABSTRACT “IRISH BLOOD, ENGLISH HEART”: GENDER, MODERNITY, AND “THIRD-WAY” REPUBLICANISM IN THE FORMATION OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC Kenneth L. Shonk, Jr., B.A., M.A., M.A.T. Marquette University, 2010 Led by noted Irish statesman Eamon de Valera, a cadre of former members of the militaristic republican organization Sinn Féin split to form Fianna Fáil with the intent to reconstitute Irish republicanism so as to fit within the democratic frameworks of the Irish Free State. Beginning with its formation in 1926, up through the passage of a republican constitution in 1937 that was recognized by Great Britain the following year, Fianna Fáil had successfully rescued the seemingly moribund republican movement from complete marginalization. Using gendered language to forge a nexus between primordial cultural nationalism and modernity, Fianna Fáil’s nationalist project was tantamount to efforts anti- hegemonic as well as hegemonic. -

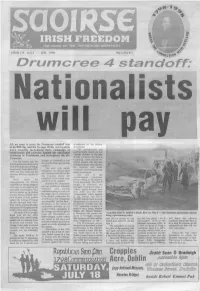

Drumcree 4 Standoff: Nationalists Will

UIMH 135 JULY — IUIL 1998 50p (USA $1) Drumcree 4 standoff: Nationalists will AS we went to press the Drumcree standoff was climbdown by the British in its fifth day and the Orange Order and loyalists government. were steadily increasing their campaign of The co-ordinated and intimidation and pressure against the nationalist synchronised attack on ten Catholic churches on the night residents in Portadown and throughout the Six of July 1-2 shows that there is Counties. a guiding hand behind the For the fourth year the brought to a standstill in four loyalist protests. Mo Mowlam British government looks set to days and the Major government is fooling nobody when she acts back down in the face of Orange caved in. the innocent and seeks threats as the Tories did in 1995, The ease with which "evidence" of any loyalist death 1996 and Tony Blair and Mo Orangemen are allowed travel squad involvement. Mowlam did (even quicker) in into Drurncree from all over the Six Counties shows the The role of the 1997. constitutional nationalist complicity of the British army Once again the parties sitting in Stormont is consequences of British and RUC in the standoff. worth examining. The SDLP capitulation to Orange thuggery Similarly the Orangemen sought to convince the will have to be paid by the can man roadblocks, intimidate Garvaghy residents to allow a nationalist communities. They motorists and prevent 'token' march through their will be beaten up by British nationalists going to work or to area. This was the 1995 Crown Forces outside their the shops without interference "compromise" which resulted own homes if they protest from British policemen for in Ian Paisley and David against the forcing of Orange several hours. -

Carloviana-No-34-1986 87.Pdf

SPONSORS ARD RI DRY CLEANERS ROYAL HOTEL, CARLOW BURRIN ST. & TULLOW ST., CARLOW. Phone 31935. SPONGING & PRESSING WHILE YOU WAIT, HAND FINISHED SERVICE A PERSONAL HOTEL OF QUALITY Open 8.30 to 6.00 including lunch hour. 4 Hour Service incl. Saturday Laundrette, Kennedy St BRADBURYS· ,~ ENGAGEMENT AND WEDDING RINGS Bakery, Confectionery, Self-Service Restaurant ~e4~{J MADE TO YOUR DESIGN TULLOW STREET, CARLOW . /lf' Large discount on Also: ATHY, PORTLAOISE, NEWBRIDGE, KILKENNY JEWELLERS of Carlow gifts for export CIGAR DIVAN TULLY'S TRAVEL AGENCY NEWSAGENT, CONFECTIONER, TOBACCONIST, etc. DUBLIN ST., CARLOW TULLOW ST., CARLOW. Phone 31257 BRING YOUR FRIENDS TO A MUSICAL EVENING IN CARLOW'S UNIQUE MUSIC LOUNGE EACH GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA SATURDAY AND SUNDAY. Phone No. 27159 NA BRAITHRE CRIOSTA], CEATHARLACH BUNSCOIL AGUS MEANSCOIL SMYTHS of NEWTOWN SINCE 1815 DEERPARK SERVICE STATION MICHAEL DOYLE TYRE SERVICE & ACCESSORIES BUILDERS PROVIDERS, GENERAL HARDWARE "THE SHAMROCK", 71 TULLOW ST., CARLOW DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. PHONE 31414 Phone 31847 THOMAS F. KEHOE Specialist Livestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Farm Sales and Lettings, SEVEN OAKS HOTEL Property and Estate Agent. DINNER DANCES* WEDDING RECEPTIONS* PRIVATE Agent for the Irish Civil Service Building Society. PARTIES * CONFERENCES * LUXURY LOUNGE 57 DUBLIN ST., CARLOW. Telephone 0503/31678, 31963 ATHY RD., CARLOW EILIS Greeting Cards, Stationery, Chocolates, AVONMORE CREAMERIES LTD. Whipped Ice Cream and Fancy Goods GRAIGUECULLEN, CARLOW. Phone 31639 138 TULLOW STREET DUNNY'$ MICHAEL WHITE, M.P.S.I. VETERINARY & DISPENSING CHEMIST BAKERY & CONFECTIONERY PHOTOGRAPHIC & TOILET GOODS CASTLE ST., CARLOW. Phone 31151 39 TULLOW ST., CARLOW. Phone 31229 CARLOW SCHOOL OF MOTORING LTD. A. O'BRIEN (VAL SLATER)* EXPERT TUITION WATCHMAKER & JEWELLER 39 SYCAMORE ROAD. -

The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather

Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall A Thesis in the PhD Humanities Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2012 © Heather Macdougall, 2012 ABSTRACT Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2012 This dissertation investigates the history of film production in the minority language of Irish Gaelic. The objective is to determine what this history reveals about the changing roles of both the national language and national cinema in Ireland. The study of Irish- language film provides an illustrative and significant example of the participation of a minority perspective within a small national cinema. It is also illustrates the potential role of cinema in language maintenance and revitalization. Research is focused on policies and practices of filmmaking, with additional consideration given to film distribution, exhibition, and reception. Furthermore, films are analysed based on the strategies used by filmmakers to integrate the traditional Irish language with the modern medium of film, as well as their motivations for doing so. Research methods included archival work, textual analysis, personal interviews, and review of scholarly, popular, and trade publications. Case studies are offered on three movements in Irish-language film. First, the Irish- language organization Gael Linn produced documentaries in the 1950s and 1960s that promoted a strongly nationalist version of Irish history while also exacerbating the view of Irish as a “private discourse” of nationalism. Second, independent filmmaker Bob Quinn operated in the Irish-speaking area of Connemara in the 1970s; his fiction films from that era situated the regional affiliations of the language within the national context. -

Sample Answers

Write an Essay | Sample Answers An Córas Oideachais (Education System) 1 Bochtanacht in Éirinn (Poverty in Ireland) 4 Na Meáin Chumarsáide (The Media) 7 Daoine Óga (The youth) 9 An Timpeallacht (Environmnent) 12 Cúrsaí Polaitiúla (Politics) 12 An Córas Oideachais (Education System) “Tá géarghá le córas nua oideachais in Éirinn” (We need a new education system in Ireland) Tá mé idir dhá cheann na meá (between two states of mind) mar gheall ar an gceist seo. Ní lia duine ná tuairim (everyone has their own opinion), ach creidim féin go pearsanta go mbaineann idir bhuntáistí agus mí-bhuntáistí leis an gcóras oideachais in Éirinn. Ní túisce (no sooner) a chonaic mé teideal na haiste seo ná rug mé greim ar mo pheann chun mo chuid tuairimí a bhreacadh síos. Ná dean dearmad go mbíonn dhá thaobh ar gach scéal. Ar an iomlán, ní aontaím leis an ráiteas go huile is go hiomlán (completely). Ar an gcéad dul síos, áfach, tá an córas oideachais ró-acadúil (too academic) dar liom. Tá dúshláin mhóra (big challenges) ann maidir le hoideachas triú leibhéal. Tá brú millteanach (enormous pressure) á chur ar scoláirí. Tá a lán fadhbanna ann chomh maith le córas na bpointí agus níl sé ceart ná Write an Essay | Sample Answers 1 cothrom (it’s not fair or just). Mar sin féin, imíonn sin agus tagann seo (times are changing), agus anois tá an córas ag feabhsú go mall (improving slowly). Ar dtús, breathnóidh mé ar (I will look at) na buntáistí a bhaineann leis an gcóras oideachais. Sa chóras atá againn, cuirtear béim ar (emphasis on) fhoghlaim teangacha. -

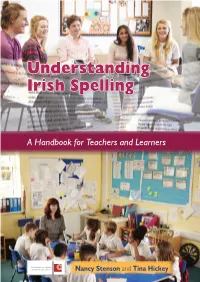

Understanding Irish Spelling

Understanding Irish Spelling A Handbook for Teachers and Learners Nancy Stenson and Tina Hickey Understanding Irish Spelling A Handbook for Teachers and Learners Nancy Stenson and Tina Hickey i © Stenson and Hickey 2018 ii Acknowledgements The preparation of this publication was supported by a grant from An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta, and we wish to express our sincere thanks to COGG, and to Muireann Ní Mhóráin and Pól Ó Cainín in particular. We acknowledge most gratefully the support of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship scheme for enabling this collaboration through its funding of an Incoming International Fellowship to the first author, and to UCD School of Psychology for hosting her as an incoming fellow and later an as Adjunct Professor. We also thank the Fulbright Foundation for the Fellowship they awarded to Prof. Stenson prior to the Marie Curie fellowship. Most of all, we thank the educators at first, second and third level who shared their experience and expertise with us in the research from which we draw in this publication. We benefitted significantly from input from many sources, not all of whom can be named here. Firstly, we wish to thank most sincerely all of the participants in our qualitative study interviews, who generously shared their time and expertise with us, and those in the schools that welcomed us to their classrooms and facilitated observation and interviews. We also wish to thank the participants at many conferences, seminars and presentations, particularly those in Bangor, Berlin, Brighton, Hamilton and Ottawa, as well as those in several educational institutions in Ireland who offered comments and suggestions. -

Cultural Connections Cultural Connections

Donegal County Council 2009 Donegal – 2014 Services Division Cultural Plan For Strategic Connections Cultural Cultural Connections Strategic Plan For Cultural Services Division Donegal County Council 2009 – 2014 Ceangail Cultúrtha Ceangail do Rannán na Seirbhísí Cultúrtha Plean Straitéiseach Chontae Dhún na nGall 2009 – 2014 Comhairle comhairle chontae dhún na ngall donegal county council The mission of the Cultural Services Division of Donegal County Council is to enrich life, enhance sense of identity, increase cultural and social opportunities and conserve cultural inheritance for present and future generations by maintaining and developing Library, Arts, Museum, Archive and Heritage Services. Library Arts Museum Heritage Archive Lough Veagh and The Derryveagh Mountains, Glenveagh National Park, Co. Donegal. Photo: Joseph Gallagher 2 Foreword 3 Preface 4 Introduction 5 Section 1 Description of Cultural Services Division 11 Section 2 Review 2001-2008. Key Achievements and Outputs 27 Section 3 Operating Environment, Policy and Legislative Context 35 Section 4 Consultation and Preparation of the Plan 41 Section 5 Statement of Strategy – Mission, Goals, Objectives, Actions 61 Section 6 Case Studies 71 Appendices Strategic Plan for Cultural Services Division Donegal County Council 1 Foreword This is the first cultural strategy for the Cultural Services Division of Donegal County Council in which the related though distinct areas of Libraries, Arts and Heritage work together to 5 common goals. Donegal County Council takes a proactive approach to the provision of cultural services in the county, continuously evolving to strengthen services, set up new initiatives, create and take up diverse opportunities to meet emerging needs. Donegal gains widespread recognition for this approach and the Council intends to continue to lead and support developments in this core area. -

National Library of Ireland

ABOUT TOWN (DUNGANNON) AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) No. 1, May - Dec. 1986 Feb. 1950- April 1951 Jan. - June; Aug - Dec. 1987 Continued as Jan.. - Sept; Nov. - Dec. 1988 AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Jan. - Aug; Oct. 1989 May 1951 - Dec. 1971 Jan, Apr. 1990 April 1972 - April 1975 All Hardcopy All Hardcopy Misc. Newspapers 1982 - 1991 A - B IL B 94109 ADVERTISER (WATERFORD) AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Mar. 11 - Sept. 16, 1848 - Microfilm See AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) ADVERTISER & WATERFORD MARKET NOTE ALLNUTT'S IRISH LAND SCHEDULE (WATERFORD) (DUBLIN) March 4 - April 15, 1843 - Microfilm No. 9 Jan. 1, 1851 Bound with NATIONAL ADVERTISER Hardcopy ADVERTISER FOR THE COUNTIES OF LOUTH, MEATH, DUBLIN, MONAGHAN, CAVAN (DROGHEDA) AMÁRACH (DUBLIN) Mar. 1896 - 1908 1956 – 1961; - Microfilm Continued as 1962 – 1966 Hardcopy O.S.S. DROGHEDA ADVERTISER (DROGHEDA) 1967 - May 13, 1977 - Microfilm 1909 - 1926 - Microfilm Sept. 1980 – 1981 - Microfilm Aug. 1927 – 1928 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1982 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1929 - Microfilm 1983 - Microfilm Incorporated with DROGHEDA ARGUS (21 Dec 1929) which See. - Microfilm ANDERSONSTOWN NEWS (ANDERSONSTOWN) Nov. 22, 1972 – 1993 Hardcopy O.S.S. ADVOCATE (DUBLIN) 1994 – to date - Microfilm April 14, 1940 - March 22, 1970 (Misc. Issues) Hardcopy O.S.S. ANGLO CELT (CAVAN) Feb. 6, 1846 - April 29, 1858 ADVOCATE (NEW YORK) Dec. 10, 1864 - Nov. 8, 1873 Sept. 23, 1939 - Dec. 25th, 1954 Jan. 10, 1885 - Dec. 25, 1886 Aug. 17, 1957 - Jan. 11, 1958 Jan. 7, 1887 - to date Hardcopy O.S.S. (Number 5) All Microfilm ADVOCATE OR INDUSTRIAL JOURNAL ANOIS (DUBLIN) (DUBLIN) Sept. 2, 1984 - June 22, 1996 - Microfilm Oct. 28, 1848 - Jan 1860 - Microfilm ANTI-IMPERIALIST (DUBLIN) AEGIS (CASTLEBAR) Samhain 1926 June 23, 1841 - Nov. -

Publications

Publications National Newspapers Evening Echo Irish Examiner Sunday Business Post Evening Herald Irish Field Sunday Independent Farmers Journal Irish Independent Sunday World Irish Daily Star Irish Times Regional Newspapers Anglo Celt Galway City Tribune Nenagh Guardian Athlone Topic Gorey Echo New Ross Echo Ballyfermot Echo Gorey Guardian New Ross Standard Bray People Inish Times Offaly Express Carlow Nationalist Inishowen Independent Offaly Independent Carlow People Kerryman Offaly Topic Clare Champion Kerry’s Eye Roscommon Herald Clondalkin Echo Kildare Nationalist Sligo Champion Connacht Tribune Kildare Post Sligo Weekender Connaught Telegraph Kilkenny People South Tipp Today Corkman Laois Nationalist Southern Star Donegal Democrat Leinster Express Tallaght Echo Donegal News Leinster Leader The Argus Donegal on Sunday Leitrim Observer The Avondhu Donegal People’s Press Letterkenny Post The Carrigdhoun Donegal Post Liffey Champion The Nationalist Drogheda Independent Limerick Chronnicle Tipperary Star Dublin Gazette - City Limerick Leader Tuam Herald Dublin Gazette - North Longford Leader Tullamore Tribune Dublin Gazette - South Lucan Echo Waterford News & Star Dublin Gazette - West Lucan Echo Western People Dundalk Democrat Marine Times Westmeath Examiner Dungarvan Leader Mayo News Westmeath Independent Dungarvan Observer Meath Chronnicle Westmeath Topic Enniscorthy Echo Meath Topic Wexford Echo Enniscorthy Guardian Midland Tribune Wexford People Fingal Independent Munster Express Wicklow People Finn Valley Post Munster Express Magazines -

The Call of the Wild Geese: an Ethnography of Diasporic Irish Language Revitalization in Southern and Eastern Ontario

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scholarship@Western Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-20-2013 12:00 AM The Call of the Wild Geese: An Ethnography of Diasporic Irish Language Revitalization in Southern and Eastern Ontario Jonathan R. Giles The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Tania Granadillo The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Jonathan R. Giles 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Linguistic Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Giles, Jonathan R., "The Call of the Wild Geese: An Ethnography of Diasporic Irish Language Revitalization in Southern and Eastern Ontario" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1448. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1448 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CALL OF THE WILD GEESE: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF DIASPORIC IRISH LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION IN SOUTHERN AND EASTERN ONTARIO Monograph by Jonathan Giles Graduate Program in Anthropology and Collaborative Graduate Program in Migration and Ethnic Relations A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jonathan Giles 2013 Abstract This research examines the ideological and social dynamics that govern the use of the Irish language by a network of speakers and learners in Southern and Eastern Ontario. -

Scéim Teanga Do RTÉ 2019-2022 Faoi Alt 15 D'acht Na Dteangacha

Scéim Teanga do RTÉ 2019-2022 Faoi Alt 15 d’Acht na dTeangacha Oifigiúla 2003 Language Scheme for RTÉ 2019-2022 Under Section 15 of the Official Languages Act 2003 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Introduction from RTÉ Director-General ............................................................................................... 3 Chapter One: Preparation of the RTÉ Language Scheme ................................................................. 4 Commencement date ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter Two: Overview of Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) ............................................................... 6 RTÉ’s Vision: ............................................................................................................................................. 7 RTÉ’s Mission is to: ................................................................................................................................ 7 RTÉ’s Values:............................................................................................................................................. 7 RTÉ’s organisational structure ................................................................................................................... 7 The Board of RTÉ .................................................................................................................................... 8 The RTÉ Executive .................................................................................................................................