Remembering St. Thomas More's Vocation Veryl Victoria Miles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

Anniversary Season

th ASOLO REPERTORY THEATRE o ANNIVERSARY6 SEASON ASOLO REPERTORY THEATRE th 6oANNIVERSARY DINNER November 26, 2018 The Westin | Sarasota 6pm | Cocktail Reception 7pm | Dinner, Presentation and Award Ceremony • Vic Meyrich Tech Award • Bradford Wallace Acting Award 03 HONOREES Honoring 12 artists who made an indelible impact on the first decade and beyond. 04-05 WELCOME LETTER 06-11 60 YEARS OF HISTORY 12-23 HONOREE INTERVIEWS 24-27 LIST OF PRODUCTIONS From 1959 through today rep 31 TRIBUTES o l aso HONOREES Steve Hogan Assistant Technical Director, 1969-1982 Master Carpenter, 1982-2001 Shop Foreman, 2001-Present Polly Holliday Resident Acting Company, 1962-1972 Vic Meyrich Technical Director, 1968-1992 Production Manager, 1992-2017 Production Manager & Operations Director, 2017-Present Howard Millman Actor, 1959 Managing Director, Stage Director, 1968-1980 Producing Artistic Director, 1995-2006 Stephanie Moss Resident Acting Company, 1969-1970 Assistant Stage Manager, 1972-1990 Bob Naismith Property Master, 1967-2000 Barbara Redmond Resident Acting Company, 1968-2011 Director, Playwright, 1996-2003 Acting Faculty/Head of Acting, FSU/Asolo Conservatory, 1998-2011 Sharon Spelman Resident Acting Company, 1968-1971 and 1996-2010 Eberle Thomas Director, Actor, Playwright, 1960-1966 rep Co-Artistic Director, 1966-1973 Director, Actor, Playwright, 1976-2007 Brad Wallace o Resident Acting Company, 1961-2008 l Marian Wallace Box Office Associate, 1967-1968 Stage Manager, 1968-1969 Production Stage Manager, 1969-2010 John M. Wilson Master Carpenter, 1969-1977 asolorep.org | 03 aso We are grateful you are here tonight to celebrate and support Asolo Rep — MDE/LDG PHOTO WHICH ONE ??? Nationally renowned, world-class theatre, made in Sarasota. -

Clothes Playbill

Ticketing Services Provided By WHITE HORSE THEATER COMPANY PRESENTS..... White Horse Theater website & the contents of this playbill (excluding the front cover) are designed, produced and maintained by Right Side of NY. www.WhiteHorseTheater.com February 5 to 21, 2010 ❖ Hudson Guild Theatre “Life ended for me when Zelda and I crashed. If she could get well, I would be happy again. Otherwise, never.” - SPECIAL POST-SHOW DISCUSSION ON F. Scott Fitzgerald* SUNDAY, FEB 14TH! With Renowned Williams Scholar Dr. Annette J. Saddik "I determined to find an impersonal escape, a world in which I and Nancy Milford, author of Zelda could express myself and walk without the help of somebody who was always far from me." - Zelda Fitzgerald** Moderated by Jennifer-Scott Mobley, Ph.D. Candidate in Theater History & Criticism, CUNY Graduate Center Clothes for a Summer Hotel, Mr. Williams’ highly theatrical and evocative “ghost play”, imagines an ethereal final meeting Dr. Saddik is an Associate Professor in the English between the restless ghosts of literary great F. Scott Fitzgerald Department at New York City College of Technology and his wife Zelda. Set on a windy hilltop at the gates of the Asheville, NC asylum where Zelda was institutionalized before her (CUNY), a teacher in the Ph.D. Program in Theatre at the death by fire in 1948, a desperate Scott pleads for CUNY Graduate Center and the author of Contemporary reconciliation while Zelda blames him for her failed writing American Drama and The Politics of Reputation: The career and ensuing madness. Taking extraordinary liberties with time and place, Clothes fuses the past, present and future as Critical Reception of Tennessee Williams’ Later Plays. -

Robert Bolt Playwright

Robert Bolt Playwright Robert Oxton Bolt was born in Sale in Manchester on 15 August 1924, the son of a shopkeeper. Early education at Manchester Grammar School was followed by a history degree at Manchester University. After serving in the Royal Air Force in World War II, Bolt qualified as a teacher and taught English at the prestigious private school Millfield between 1950 and 1958. It was here that, in his spare time, he wrote both radio and stage plays. Many of his radio plays received an airing and he also did some producing. In 1958, encouraged by the London success of his play Flowering Cherry , he gave up teaching to concentrate full time on his writing. In 1960 he had two plays running in London, The Tiger and The Horse and A Man for All Seasons . The eponymous role of Sir Thomas More shot actor Paul Scofield to stardom, and A Man for All Seasons proved a huge hit both in London’s West End and on Broadway, where in 1962 it was voted Best Foreign Play of the Year. This success attracted the attention of Hollywood, and producer Sam Spiegel approached Bolt to revise Michael Wilson’s script for Lawrence of Arabia . Directed by David Lean, it was Bolt’s first successful screenplay and he received an Academy Award nomination for it. Bolt won his first Oscar for his next collaboration with Lean, Doctor Zhivago in 1965. In 1966 his screen adaptation of A Man for All Seasons won him a second Oscar. Meanwhile, on stage, Bolt produced Gentle Jack in 1963 and a play for children, The Thwarting of Baron Bolligrew at Christmas 1965. -

A Legal Career for All Seasons: Remembering St. Thomas Moreâ

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 2006 A Legal Career for All Seasons: Remembering St. Thomas More’s Vocation Veryl Victoria Miles The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Veryl Victoria Miles, A Legal Career for All Seasons: Remembering St. Thomas More’s Vocation, 20 NOTRE DAME J. L. ETHICS & PUB. POL’Y 419 (2006). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A LEGAL CAREER FOR ALL SEASONS: REMEMBERING ST. THOMAS MORE'S VOCATION VERYL VICTORIA MILES* The vast majority of the work taking place in most law schools is the preparation of law students for the practice of law; namely, to teach legal theory and doctrine, legal analysis, writing, and advocacy. In sum, the goal of most law schools is to teach the many different skills required in law practice and the profes- sional rules of legal ethics. What appears to be lacking in the preparation of future lawyers are lessons on how to incorporate this vast amount of specialized learning and skill in ways that will be harmonious with the personal, moral, and ethical values that they possessed at the commencement of their legal education. -

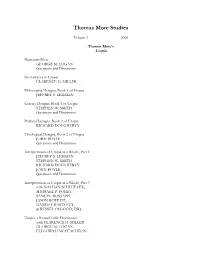

Thomas More Studies 1 (2006) 3 Thomas More Studies 1 (2006) George M

Thomas More Studies Volume 1 2006 Thomas More’s Utopia Humanist More GEORGE M. LOGAN Questions and Discussion No Lawyers in Utopia CLARENCE H. MILLER Philosophic Designs, Book 1 of Utopia JEFFREY S. LEHMAN Literary Designs, Book 1 of Utopia STEPHEN W. SMITH Questions and Discussion Political Designs, Book 2 of Utopia RICHARD DOUGHERTY Theological Designs, Book 2 of Utopia JOHN BOYLE Questions and Discussion Interpretation of Utopia as a Whole, Part 1 JEFFREY S. LEHMAN STEPHEN W. SMITH RICHARD DOUGHERTY JOHN BOYLE Questions and Discussion Interpretation of Utopia as a Whole, Part 2 with NATHAN SCHLUETER, MICHAEL P. FOLEY, SAMUEL BOSTAPH, JASON BOFETTI, GABRIEL BARTLETT, & RUSSEL OSGOOD, ESQ. Utopia, a Round Table Discussion with CLARENCE H. MILLER GEORGE M. LOGAN ELIZABETH MCCUTCHEON The Development of Thomas More Studies Remarks CLARENCE H. MILLER ELIZABETH MCCUTCHEON GEORGE M. LOGAN Interrogating Thomas More Interrogating Thomas More: The Conundrums of Conscience STEPHEN D. SMITH, ESQ. Response JOSEPH KOTERSKI, SJ Reply STEPHEN D. SMITH, ESQ. Questions and Discussion Papers On “a man for all seasons” CLARENCE H. MILLER Sir Thomas More’s Noble Lie NATHAN SCHLUETER Law in Sir Thomas More’s Utopia as Compared to His Lord Chancellorship RUSSEL OSGOOD, ESQ. Variations on a Utopian Diversion: Student Game Projects in the University Classroom MICHAEL P. FOLEY Utopia from an Economist’s Perspective SAMUEL BOSTAPH These are the refereed proceedings from the 2005 Thomas More Studies Conference, held at the University of Dallas, November 4-6, 2005. Intellectual Property Rights: Contributors retain in full the rights to their work. George M. Logan 2 exercises preparing himself for the priesthood.”3 The young man was also extremely interested in literature, especially as conceived by the humanists of the period. -

Lessons from Thomas More's Dilemma of Conscience: Reconciling the Clash Between a Lawyer's Beliefs and Professional Expectations

St. John's Law Review Volume 78 Number 4 Volume 78, Fall 2004, Number 4 Article 1 Lessons From Thomas More's Dilemma of Conscience: Reconciling the Clash Between a Lawyer's Beliefs and Professional Expectations Blake D. Morant Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES LESSONS FROM THOMAS MORE'S DILEMMA OF CONSCIENCE: RECONCILING THE CLASH BETWEEN A LAWYER'S BELIEFS AND PROFESSIONAL EXPECTATIONS BLAKE D. MORANTt TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODU CTION .................................................................................... 966 I. JURISPRUDENTIAL ROOTS OF THE CLASH BETWEEN PERSONAL BELIEFS AND PROFESSIONAL EXPECTATIONS ................................ 972 A. More's Beliefs as Natural Law Conceptualizations................ 975 B. Expectations of the Sovereign-Henry VIII's Proclamationsas PositiveLaw ............................................... 981 C. Contextualism-The Searchfor Accommodation or Compromise Between Conflicting Beliefs and Expectations ..................................................................... 985 D. More's Tacit Embrace of Contextualism................................. 990 II. THE RELEVANCE OF THOMAS MORE'S DILEMMA TO THE CONTEMPORARY PRACTICE OF LAW .............................................. 993 A. Adherence to Conviction Versus Accommodation of the Sovereign-A ContemporaryNarrative .................................. 994 t Professor of Law and Director of the Frances Lewis Law Center, Washington and Lee University School of Law. B.A. and J.D., University of Virginia. The inspiration for this Article was the invitation to deliver a lecture during the July 6, 2003 Saint Thomas More Commemorative Service at St. -

Peninsula Players Theatre Will Present a Reading of "The Trip to Bountiful

Peninsula Players Theatre will present a reading of "The Trip to Bountiful" by Horton Foote, a moving and riveting story from one of our country's greatest writers, at Björklunden 7p.m., Monday, Feb. 3. The play readings are produced with support and in coordination with Door County Reads and its exploration of "The Memory of Old Jack" by Wendell Berry. Join the Players reading and travel with widow Carrie Watts who yearns to go back to the Gulf Coast town where she grew up and raised her family. Admission is free. Berry, a noted poet, novelist, farmer and conservationist, is often described as a 21st century Henry David Thoreau. His native Kentucky and its rural values have inspired his more than 40 books. "Berry is very interested in what urbanization and industrialization have done to our country and its agricultural community," said Players Artistic Director Greg Vinkler. "And he is also involved in conservation, ecology, poetry - a wide variety of interests interconnected by his interest in the human equation in all this. "In selecting our play to read in conjunction with Berry's book, I decided to go in a direction in which memory, change, being an individual and the importance of one's roots in one's life (things which play an enormous role in 'The Memory of Old Jack') all play a part." Greg Vinkler - Artistic Director President Clinton noted when awarding Horton Foote the National Medal of Arts in 2000: "His work is rooted in the tales, the troubles, the heartbreak, and the hopes of all he heard and saw. -

A Study Guide, with Theatrical Emphasis, for Robert Bolt's Play a Man for All Seasons For

A Study Guide, with Theatrical Emphasis, For Meg for Robert Bolt’s Play A Man for All Seasons by Arthur Kincaid V. Questions for Discussion and Essay Writing…..….…....…105 Contents VI. List of Works Consulted……………….………..………..109 I. Introduction…………………………..……….………..….5 II. General Background 1. Thomas More…………………………..….……...……..6 2. Henry VIII and Thomas More…...……….…….….…..10 3. Renaissance Humanism…...……………....…….….…..12 4. Robert Bolt…………………………………...….…..…13 5. Theatrical Influences………………………….......…....15 III. Classroom & Theatre Performance 1. What Is Theatre?……………...………….….…….....…19 2. Aspects of a Play...……………………………………..22 3. Classroom Performance………...………………..…......30 4. Full Performance………………………………………31 5. Acting Exercises……………….……..………….....…..37 IV. Notes and Questions for Study and Performance 1. Act 1, A Man for All Seasons……………...…….....…..….47 2. Act 2, A Man for All Seasons……………....……..…....….74 5 www.thomasmorestudies.org Kincaid’s Guide: A Man for All Seasons 6 II. General Background I. Introduction 1. Sir Thomas More This guide is designed to give a performance orientation to the study of Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons. It attempts to encourage teachers Nobody wants to be a hero. You go through life giving up and students to discover the work as a play to be performed. You can use parts of yourself – a hope, a dream, an ambition, a belief, a liking, this guide for inactive classroom study if you wish, but it would be much a piece of self-respect. But in every man there is something he more interesting and productive to use it as a stimulus to performance cannot give up and still remain himself – a core, an identity, a work of some sort, whether it be rehearsing a scene in class or a full thing that is summed up for him by the sound of his own name on his own ears. -

Historical Theater Programs Collection MS-87 Wright State

Historical Theater Programs Collection (MS-87) Guide This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 21, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Wright State University Libraries, Special Collections and Archives Special Collections and Archives 3640 Colonel Glenn Hwy Dayton, OH 45435-0001 [email protected] URL: http://www.libraries.wright.edu/special Historical Theater Programs Collection (MS-87) Guide Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Contents ...................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement ............................................................... .................................................................. 3 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................... 4 Collection Inventory ............................................................... ...................................................... 4 Series 1: Plays and Musicals ............................................................... ....................................... 4 Series 2: Animal Shows & Races ............................................................................................. 29 Series 3: Concerts ............................................................... ..................................................... -

THE FATHER Promises to Be a Profoundly Moving, Memorable Evening of Theatre

CONTACT: Nancy Richards – 917-873-6389 (cell) /[email protected] MEDIA PAGE: www.northcoastrep.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE: NORTH COAST REP PRESENTS WEST COAST PREMIERE OF INTERNATIONAL AWARD-WINNING SENSATION THE FATHER By Florian Zeller Translated By Christopher Hampton Performances Beginning Wednesday, May 30, 2018 Running Through Sunday, June 24, 2018 Directed by David Ellenstein Solana Beach, CA, San Diego audiences will be treated to a play that the London Telegraph called “an unqualified triumph” as North Coast Rep stages the West Coast premiere of THE FATHER. A sensation in Paris, London and New York, and honored with a war chest of awards including a Tony nomination for Best Play, THE FATHER promises to be a profoundly moving, memorable evening of theatre. André was once a tap dancer who lives with his daughter Anne and her husband Antoine. Or was he an engineer whose daughter Anne lives in London with her new lover, Pierre? The thing is, he is still wearing his pajamas, and he can’t find his watch. He is starting to wonder if he’s losing control. This is must-see theatre for the discerning theatre- goer. David Ellenstein directs James Sutorius,* Robyn Cohen, Matthew Salazar-Thompson, Jacque Wilke,* Richard Baird,* and Shana Wride.* The design team includes Marty Burnett (Scenic Design), Matthew Novotny (Lighting Design), Melanie Chen Cole (Sound), Elisa Benzoni (Costumes), and Holly Gillard (Prop Design). Aaron Rumley* is the Stage Manager. *The actor or stage manager appears through the courtesy of Actors’ Equity Association, the union of professional actors and stage managers in the United States. -

Download Playbill

Max McLean, Founder & Artistic Director a Man for all easons Sby Robert Bolt Max McLean, Founder & Artistic Director Presents a for Man all easons Sby Robert Bolt With John Ahlin Harry Bouvy Todd Cerveris Michael Countryman Trent Dawson Sean Dugan Carolyn McCormick David McElwee Kevyn Morrow Kim Wong Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Composer/Sound Design Steven C. Kemp Theresa Squire Aaron Porter John Gromada Dialect Coach Casting Director Claudia Hill-Sparks McCorkle Casting Ltd Marketing & Advertising Press Relations The Pekoe Group Matt Ross Public Relations Production Manager General Management Stage Manager Lew Mead Aruba Productions Kelly Burns Executive Producer Ken Denison Directed by Christa Scott-Reed CAST OF CHARACTERS (in order of appearance) The Common Man .................................................................... Harry Bouvy Sir Thomas More ......................................................... Michael Countryman Richard Rich ......................................................................... David McElwee The Duke of Norfolk .............................................................. Kevyn Morrow Lady Alice More/Woman ................................................Carolyn McCormick Margaret More ..............................................................................Kim Wong Cardinal Wolsey/Sigñor Chapuys ................................................. John Ahlin Thomas Cromwell .................................................................. Todd Cerveris William Roper/Archbishop