The Power Wall and Multicore Computers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accelerating HPL Using the Intel Xeon Phi 7120P Coprocessors

Accelerating HPL using the Intel Xeon Phi 7120P Coprocessors Authors: Saeed Iqbal and Deepthi Cherlopalle The Intel Xeon Phi Series can be used to accelerate HPC applications in the C4130. The highly parallel architecture on Phi Coprocessors can boost the parallel applications. These coprocessors work seamlessly with the standard Xeon E5 processors series to provide additional parallel hardware to boost parallel applications. A key benefit of the Xeon Phi series is that these don’t require redesigning the application, only compiler directives are required to be able to use the Xeon Phi coprocessor. Fundamentally, the Intel Xeon series are many-core parallel processors, with each core having a dedicated L2 cache. The cores are connected through a bi-directional ring interconnects. Intel offers a complete set of development, performance monitoring and tuning tools through its Parallel Studio and VTune. The goal is to enable HPC users to get advantage from the parallel hardware with minimal changes to the code. The Xeon Phi has two modes of operation, the offload mode and native mode. In the offload mode designed parts of the application are “offloaded” to the Xeon Phi, if available in the server. Required code and data is copied from a host to the coprocessor, processing is done parallel in the Phi coprocessor and results move back to the host. There are two kinds of offload modes, non-shared and virtual-shared memory modes. Each offload mode offers different levels of user control on data movement to and from the coprocessor and incurs different types of overheads. In the native mode, the application runs on both host and Xeon Phi simultaneously, communication required data among themselves as need. -

Chapter 1: Computer Abstractions and Technology 1.6 – 1.7: Performance and Power

Chapter 1: Computer Abstractions and Technology 1.6 – 1.7: Performance and power ITSC 3181 Introduction to Computer Architecture https://passlaB.githuB.io/ITSC3181/ Department of Computer Science Yonghong Yan [email protected] https://passlab.github.io/yanyh/ Lectures for Chapter 1 and C Basics Computer Abstractions and Technology • Lecture 01: Chapter 1 – 1.1 – 1.4: Introduction, great ideas, Moore’s law, aBstraction, computer components, and program execution • Lecture 02: C Basics; Memory and Binary Systems • Lecture 03: Number System, Compilation, Assembly, Linking and Program Execution ☛• Lecture 04: Chapter 1 – 1.6 – 1.7: Performance, power and technology trends • Lecture 05: – 1.8 - 1.9: Multiprocessing and Benchmarking 2 § 1.6 Performance 1.6 Defining Performance • Which airplane has the best performance? Boeing 777 Boeing 777 Boeing 747 Boeing 747 BAC/Sud BAC/Sud Concorde Concorde Douglas Douglas DC- DC-8-50 8-50 0 100 200 300 400 500 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 Passenger Capacity Cruising Range (miles) Boeing 777 Boeing 777 Boeing 747 Boeing 747 BAC/Sud BAC/Sud Concorde Concorde Douglas Douglas DC- DC-8-50 8-50 0 500 1000 1500 0 100000 200000 300000 400000 Cruising Speed (mph) Passengers x mph 3 Response Time and Throughput • Response time çè Latency – How long it takes to do a task • Throughput çè Bandwidth – Total work done per unit time • e.g., tasks/transactions/… per hour • How are response time and throughput affected by – Replacing the processor with a faster version? – Adding more processors? • We’ll focus on response time for now… 4 Relative Performance • Define Performance = 1/Execution Time • “X is n time faster than Y”, i.e. -

45-Year CPU Evolution: One Law and Two Equations

45-year CPU evolution: one law and two equations Daniel Etiemble LRI-CNRS University Paris Sud Orsay, France [email protected] Abstract— Moore’s law and two equations allow to explain the a) IC is the instruction count. main trends of CPU evolution since MOS technologies have been b) CPI is the clock cycles per instruction and IPC = 1/CPI is the used to implement microprocessors. Instruction count per clock cycle. c) Tc is the clock cycle time and F=1/Tc is the clock frequency. Keywords—Moore’s law, execution time, CM0S power dissipation. The Power dissipation of CMOS circuits is the second I. INTRODUCTION equation (2). CMOS power dissipation is decomposed into static and dynamic powers. For dynamic power, Vdd is the power A new era started when MOS technologies were used to supply, F is the clock frequency, ΣCi is the sum of gate and build microprocessors. After pMOS (Intel 4004 in 1971) and interconnection capacitances and α is the average percentage of nMOS (Intel 8080 in 1974), CMOS became quickly the leading switching capacitances: α is the activity factor of the overall technology, used by Intel since 1985 with 80386 CPU. circuit MOS technologies obey an empirical law, stated in 1965 and 2 Pd = Pdstatic + α x ΣCi x Vdd x F (2) known as Moore’s law: the number of transistors integrated on a chip doubles every N months. Fig. 1 presents the evolution for II. CONSEQUENCES OF MOORE LAW DRAM memories, processors (MPU) and three types of read- only memories [1]. The growth rate decreases with years, from A. -

Intel Cirrascale and Petrobras Case Study

Case Study Intel® Xeon Phi™ Coprocessor Intel® Xeon® Processor E5 Family Big Data Analytics High-Performance Computing Energy Accelerating Energy Exploration with Intel® Xeon Phi™ Coprocessors Cirrascale delivers scalable performance by combining its innovative PCIe switch riser with Intel® processors and coprocessors To find new oil and gas reservoirs, organizations are focusing exploration in the deep sea and in complex geological formations. As energy companies such as Petrobras work to locate and map those reservoirs, they need powerful IT resources that can process multiple iterations of seismic models and quickly deliver precise results. IT solution provider Cirrascale began building systems with Intel® Xeon Phi™ coprocessors to provide the scalable performance Petrobras and other customers need while holding down costs. Challenges • Enable deep-sea exploration. Improve reservoir mapping accuracy with detailed seismic processing. • Accelerate performance of seismic applications. Speed time to results while controlling costs. • Improve scalability. Enable server performance and density to scale as data volumes grow and workloads become more demanding. Solution • Custom Cirrascale servers with Intel Xeon Phi coprocessors. Employ new compute blades with the Intel® Xeon® processor E5 family and Intel Xeon Phi coprocessors. Cirrascale uses custom PCIe switch risers for fast, peer-to-peer communication among coprocessors. Technology Results • Linear scaling. Performance increases linearly as Intel Xeon Phi coprocessors “Working together, the are added to the system. Intel® Xeon® processors • Simplified development model. Developers no longer need to spend time optimizing data placement. and Intel® Xeon Phi™ coprocessors help Business Value • Faster, better analysis. More detailed and accurate modeling in less time HPC applications shed improves oil and gas exploration. -

Nvidia Tesla P40 Gpu Accelerator

NVIDIA TESLA P40 GPU ACCELERATOR HIGH-PERFORMANCE VIRTUAL GRAPHICS AND COMPUTE NVIDIA redefined visual computing by giving designers, engineers, scientists, and graphic artists the power to take on the biggest visualization challenges with immersive, interactive, photorealistic environments. NVIDIA® Quadro® Virtual Data GPU 1 NVIDIA Pascal GPU Center Workstation (Quadro vDWS) takes advantage of NVIDIA® CUDA Cores 3,840 Tesla® GPUs to deliver virtual workstations from the data center. Memory Size 24 GB GDDR5 H.264 1080p30 streams 24 Architects, engineers, and designers are now liberated from Max vGPU instances 24 (1 GB Profile) their desks and can access applications and data anywhere. vGPU Profiles 1 GB, 2 GB, 3 GB, 4 GB, 6 GB, 8 GB, 12 GB, 24 GB ® ® The NVIDIA Tesla P40 GPU accelerator works with NVIDIA Form Factor PCIe 3.0 Dual Slot Quadro vDWS software and is the first system to combine an (rack servers) Power 250 W enterprise-grade visual computing platform for simulation, Thermal Passive HPC rendering, and design with virtual applications, desktops, and workstations. This gives organizations the freedom to virtualize both complex visualization and compute (CUDA and OpenCL) workloads. The NVIDIA® Tesla® P40 taps into the industry-leading NVIDIA Pascal™ architecture to deliver up to twice the professional graphics performance of the NVIDIA® Tesla® M60 (Refer to Performance Graph). With 24 GB of framebuffer and 24 NVENC encoder sessions, it supports 24 virtual desktops (1 GB profile) or 12 virtual workstations (2 GB profile), providing the best end-user scalability per GPU. This powerful GPU also supports eight different user profiles, so virtual GPU resources can be efficiently provisioned to meet the needs of the user. -

Power Measurement Tutorial for the Green500 List

Power Measurement Tutorial for the Green500 List R. Ge, X. Feng, H. Pyla, K. Cameron, W. Feng June 27, 2007 Contents 1 The Metric for Energy-Efficiency Evaluation 1 2 How to Obtain P¯(Rmax)? 2 2.1 The Definition of P¯(Rmax)...................................... 2 2.2 Deriving P¯(Rmax) from Unit Power . 2 2.3 Measuring Unit Power . 3 3 The Measurement Procedure 3 3.1 Equipment Check List . 4 3.2 Software Installation . 4 3.3 Hardware Connection . 4 3.4 Power Measurement Procedure . 5 4 Appendix 6 4.1 Frequently Asked Questions . 6 4.2 Resources . 6 1 The Metric for Energy-Efficiency Evaluation This tutorial serves as a practical guide for measuring the computer system power that is required as part of a Green500 submission. It describes the basic procedures to be followed in order to measure the power consumption of a supercomputer. A supercomputer that appears on The TOP500 List can easily consume megawatts of electric power. This power consumption may lead to operating costs that exceed acquisition costs as well as intolerable system failure rates. In recent years, we have witnessed an increasingly stronger movement towards energy-efficient computing systems in academia, government, and industry. Thus, the purpose of the Green500 List is to provide a ranking of the most energy-efficient supercomputers in the world and serve as a complementary view to the TOP500 List. However, as pointed out in [1, 2], identifying a single objective metric for energy efficiency in supercom- puters is a difficult task. Based on [1, 2] and given the already existing use of the “performance per watt” metric, the Green500 List uses “performance per watt” (PPW) as its metric to rank the energy efficiency of supercomputers. -

Clock Rate Improves Roughly Proportional to Improvement in L • Number of Transistors Improves Proportional to L2 (Or Faster)

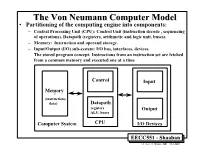

TheThe VonVon NeumannNeumann ComputerComputer ModelModel • Partitioning of the computing engine into components: – Central Processing Unit (CPU): Control Unit (instruction decode , sequencing of operations), Datapath (registers, arithmetic and logic unit, buses). – Memory: Instruction and operand storage. – Input/Output (I/O) sub-system: I/O bus, interfaces, devices. – The stored program concept: Instructions from an instruction set are fetched from a common memory and executed one at a time Control Input Memory - (instructions, data) Datapath registers Output ALU, buses Computer System CPU I/O Devices EECC551 - Shaaban #1 Lec # 1 Winter 2001 12-3-2001 Generic CPU Machine Instruction Execution Steps Instruction Obtain instruction from program storage Fetch Instruction Determine required actions and instruction size Decode Operand Locate and obtain operand data Fetch Execute Compute result value or status Result Deposit results in storage for later use Store Next Determine successor or next instruction Instruction EECC551 - Shaaban #2 Lec # 1 Winter 2001 12-3-2001 HardwareHardware ComponentsComponents ofof AnyAny ComputerComputer Five classic components of all computers: 1. Control Unit; 2. Datapath; 3. Memory; 4. Input; 5. Output } Processor Computer Keyboard, Mouse, etc. Processor Memory Devices (active) (passive) Control Input (where Unit programs, data Disk Datapath live when Output running) Display, Printer, etc. EECC551 - Shaaban #3 Lec # 1 Winter 2001 12-3-2001 CPUCPU OrganizationOrganization • Datapath Design: – Capabilities & performance characteristics of principal Functional Units (FUs): • (e.g., Registers, ALU, Shifters, Logic Units, ...) – Ways in which these components are interconnected (buses connections, multiplexors, etc.). – How information flows between components. • Control Unit Design: – Logic and means by which such information flow is controlled. – Control and coordination of FUs operation to realize the targeted Instruction Set Architecture to be implemented (can either be implemented using a finite state machine or a microprogram). -

Towards Better Performance Per Watt in Virtual Environments on Asymmetric Single-ISA Multi-Core Systems

Towards Better Performance Per Watt in Virtual Environments on Asymmetric Single-ISA Multi-core Systems Viren Kumar Alexandra Fedorova Simon Fraser University Simon Fraser University 8888 University Dr 8888 University Dr Vancouver, Canada Vancouver, Canada [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT performance per watt than homogeneous multicore proces- Single-ISA heterogeneous multicore architectures promise to sors. As power consumption in data centers becomes a grow- deliver plenty of cores with varying complexity, speed and ing concern [3], deploying ASISA multicore systems is an performance in the near future. Virtualization enables mul- increasingly attractive opportunity. These systems perform tiple operating systems to run concurrently as distinct, in- at their best if application workloads are assigned to het- dependent guest domains, thereby reducing core idle time erogeneous cores in consideration of their runtime proper- and maximizing throughput. This paper seeks to identify a ties [4][13][12][18][24][21]. Therefore, understanding how to heuristic that can aid in intelligently scheduling these vir- schedule data-center workloads on ASISA systems is an im- tualized workloads to maximize performance while reducing portant problem. This paper takes the first step towards power consumption. understanding the properties of data center workloads that determine how they should be scheduled on ASISA multi- We propose that the controlling domain in a Virtual Ma- core processors. Since virtual machine technology is a de chine Monitor or hypervisor is relatively insensitive to changes facto standard for data centers, we study virtual machine in core frequency, and thus scheduling it on a slower core (VM) workloads. saves power while only slightly affecting guest domain per- formance. -

Atmega165p Datasheet

Features • High Performance, Low Power Atmel® AVR® 8-Bit Microcontroller • Advanced RISC Architecture – 130 Powerful Instructions – Most Single Clock Cycle Execution – 32 × 8 General Purpose Working Registers – Fully Static Operation – Up to 16 MIPS Throughput at 16 MHz – On-Chip 2-cycle Multiplier • High Endurance Non-volatile Memory segments – 16 Kbytes of In-System Self-programmable Flash program memory – 512 Bytes EEPROM – 1 Kbytes Internal SRAM 8-bit – Write/Erase cyles: 10,000 Flash/100,000 EEPROM(1)(3) – Data retention: 20 years at 85°C/100 years at 25°C(2)(3) Microcontroller – Optional Boot Code Section with Independent Lock Bits In-System Programming by On-chip Boot Program with 16K Bytes True Read-While-Write Operation – Programming Lock for Software Security In-System • JTAG (IEEE std. 1149.1 compliant) Interface – Boundary-scan Capabilities According to the JTAG Standard Programmable – Extensive On-chip Debug Support – Programming of Flash, EEPROM, Fuses, and Lock Bits through the JTAG Interface Flash • Peripheral Features – Two 8-bit Timer/Counters with Separate Prescaler and Compare Mode – One 16-bit Timer/Counter with Separate Prescaler, Compare Mode, and Capture Mode – Real Time Counter with Separate Oscillator –Four PWM Channels ATmega165P – 8-channel, 10-bit ADC – Programmable Serial USART ATmega165PV – Master/Slave SPI Serial Interface – Universal Serial Interface with Start Condition Detector – Programmable Watchdog Timer with Separate On-chip Oscillator – On-chip Analog Comparator Preliminary – Interrupt and Wake-up -

Comparing the Power and Performance of Intel's SCC to State

Comparing the Power and Performance of Intel’s SCC to State-of-the-Art CPUs and GPUs Ehsan Totoni, Babak Behzad, Swapnil Ghike, Josep Torrellas Department of Computer Science, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA E-mail: ftotoni2, bbehza2, ghike2, [email protected] Abstract—Power dissipation and energy consumption are be- A key architectural challenge now is how to support in- coming increasingly important architectural design constraints in creasing parallelism and scale performance, while being power different types of computers, from embedded systems to large- and energy efficient. There are multiple options on the table, scale supercomputers. To continue the scaling of performance, it is essential that we build parallel processor chips that make the namely “heavy-weight” multi-cores (such as general purpose best use of exponentially increasing numbers of transistors within processors), “light-weight” many-cores (such as Intel’s Single- the power and energy budgets. Intel SCC is an appealing option Chip Cloud Computer (SCC) [1]), low-power processors (such for future many-core architectures. In this paper, we use various as embedded processors), and SIMD-like highly-parallel archi- scalable applications to quantitatively compare and analyze tectures (such as General-Purpose Graphics Processing Units the performance, power consumption and energy efficiency of different cutting-edge platforms that differ in architectural build. (GPGPUs)). These platforms include the Intel Single-Chip Cloud Computer The Intel SCC [1] is a research chip made by Intel Labs (SCC) many-core, the Intel Core i7 general-purpose multi-core, to explore future many-core architectures. It has 48 Pentium the Intel Atom low-power processor, and the Nvidia ION2 (P54C) cores in 24 tiles of two cores each. -

Performance of a Computer (Chapter 4) Vishwani D

ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Computer Architecture and Design Fall 2013 Performance of a Computer (Chapter 4) Vishwani D. Agrawal & Victor P. Nelson epartment of Electrical and Computer Engineering Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849 ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 1 What is Performance? Response time: the time between the start and completion of a task. Throughput: the total amount of work done in a given time. Some performance measures: MIPS (million instructions per second). MFLOPS (million floating point operations per second), also GFLOPS, TFLOPS (1012), etc. SPEC (System Performance Evaluation Corporation) benchmarks. LINPACK benchmarks, floating point computing, used for supercomputers. Synthetic benchmarks. ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 2 Small and Large Numbers Small Large 10-3 milli m 103 kilo k 10-6 micro μ 106 mega M 10-9 nano n 109 giga G 10-12 pico p 1012 tera T 10-15 femto f 1015 peta P 10-18 atto 1018 exa 10-21 zepto 1021 zetta 10-24 yocto 1024 yotta ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 3 Computer Memory Size Number bits bytes 210 1,024 K Kb KB 220 1,048,576 M Mb MB 230 1,073,741,824 G Gb GB 240 1,099,511,627,776 T Tb TB ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 4 Units for Measuring Performance Time in seconds (s), microseconds (μs), nanoseconds (ns), or picoseconds (ps). Clock cycle Period of the hardware clock Example: one clock cycle means 1 nanosecond for a 1GHz clock frequency (or 1GHz clock rate) CPU time = (CPU clock cycles)/(clock rate) Cycles per instruction (CPI): average number of clock cycles used to execute a computer instruction. -

Chap01: Computer Abstractions and Technology

CHAPTER 1 Computer Abstractions and Technology 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Eight Great Ideas in Computer Architecture 11 1.3 Below Your Program 13 1.4 Under the Covers 16 1.5 Technologies for Building Processors and Memory 24 1.6 Performance 28 1.7 The Power Wall 40 1.8 The Sea Change: The Switch from Uniprocessors to Multiprocessors 43 1.9 Real Stuff: Benchmarking the Intel Core i7 46 1.10 Fallacies and Pitfalls 49 1.11 Concluding Remarks 52 1.12 Historical Perspective and Further Reading 54 1.13 Exercises 54 CMPS290 Class Notes (Chap01) Page 1 / 24 by Kuo-pao Yang 1.1 Introduction 3 Modern computer technology requires professionals of every computing specialty to understand both hardware and software. Classes of Computing Applications and Their Characteristics Personal computers o A computer designed for use by an individual, usually incorporating a graphics display, a keyboard, and a mouse. o Personal computers emphasize delivery of good performance to single users at low cost and usually execute third-party software. o This class of computing drove the evolution of many computing technologies, which is only about 35 years old! Server computers o A computer used for running larger programs for multiple users, often simultaneously, and typically accessed only via a network. o Servers are built from the same basic technology as desktop computers, but provide for greater computing, storage, and input/output capacity. Supercomputers o A class of computers with the highest performance and cost o Supercomputers consist of tens of thousands of processors and many terabytes of memory, and cost tens to hundreds of millions of dollars.