All My Sins by Craig Ryan a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pizzas $ 99 5Each (Additional Toppings $1.40 Each)

AJW Landscaping • 910-271-3777 July 7 - 13, 2018 Mowing – Edging – Pruning – Mulching FREE Estimates – Licensed – Insured – Local References Home sweet MANAGEr’s SPECIAL home EDIUM OPPING Patricia Clarkson stars in “Sharp Objects” 2 M 2-T Pizzas $ 99 5EACH (Additional toppings $1.40 each) 1352 E Broad Ave. 1227 S Main St. Rockingham, NC 28379 Laurinburg, NC 28352 (910) 997-5696 (910) 276-6565 *Not valid with any other offers Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street Laurinburg, NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, July 7, 2018 — Laurinburg Exchange Into the fire: A crime reporter is drawn home in ‘Sharp Objects’ By Francis Babin for the big screen in 2014 by Acad- We are living in a glorious era TV Media emy Award-nominated director of small-screen book adaptations. David Fincher to great acclaim In the past, Hollywood bigwigs n recent years, we’ve seen a real from critics and audiences alike. believed that the go-to medium Irenaissance of the television mini- The adaptation was a smash suc- was the big screen, yet the tide series. These limited series dominat- cess and turned Flynn into a has turned in recent years; some ed the ‘70s and ‘80s, with such household name. stories are just better suited for heavy hitters as “Rich Man, Poor The following year, her third and television (last year’s “The Dark Man,” “Roots,” “Shogun” and most recent novel, “Dark Places,” Tower” didn’t get the memo). “North and South” winning numer- was successfully adapted into a fea- Originally envisioned as a feature ous awards and drawing viewers by ture film starring Academy Award film, “Sharp Objects” was re- the millions. -

Hollywood Nights Mark Wright and Hollywood Actor Tamer Hassan Join Forces to Raise Money with Celebrity Charity Soccer

Hollywood Nights Mark Wright and Hollywood Actor Tamer Hassan Join Forces To Raise Money with Celebrity Charity Soccer Submitted by: Butterfly PR Thursday, 26 July 2012 For immediate release 26 July 2012 Hollywood Nights Mark Wright and Hollywood Actor Tamer Hassan Join Forces To Raise Money with Celebrity Charity Soccer. Hollywood actor and cult British favourite of films like The Football Factory and The Business, Tamer Hassan and Hollywood Nights Actor Mark Wright have joined forces to organise a celebrity charity soccer event. Hassan, will lead his team The Farnborough Celebrity XI against Mark Wright’s ‘Essex FC’’ to raise money for the children’s ward at Frimley Park Hospital. The event will honour ex Wimbledon player, Kevin Cooper’s family friend Irene Grinham, who is fighting the dreaded liver disease, she has months left to live. The match will take place on Sunday, 5th August 2012; kick off at 1 O’clock at Farnborough FC, followed by a gala dinner and celebrity auction led by Tamer Hassan, donations Joe Calzaghe, Luis Suarez, Lionel Messi, Darren Campbell, Frank Lampard, STEPS memorabilia and so much more. Money raised by the event will go towards Frimley Park Hospital children's unit who offer a wide range of facilities to care for children of different age groups including a dedicated teenage unit, funds will provide a once in a life time special opportunity to enable Irene Grinham to enjoy the remaining months of her life with her family. Tamer is not taking this game lightly, using his competitive spirit to select only the fittest celebs with the skills to take on ‘Essex FC’ legends. -

Line of Duty Series 5 Ep 1 Post Production Script

Line of Duty Series 5 - Episode 1 Post Production Script – UK TX Version. 18th March 2019. 09:59:30 VT CLOCK (30 secs) World Productions Line of Duty Series 5 - Episode 1 Prog no. DRII785T/01 09:59:57 CUT TO BLACK 10:00:00 EXT. EASTFIELD DEPOT. DAY. Music 10:00:00 DUR: 4’33”. Establisher Entrance Security Gates to Eastfield Specially Police Storage Facility. composed by Carly Paradis. CONTROL (O.S.) | (Out of radio.) | Control to all patrols involved in | this operation. I can confirm that | this is a covert channel at this | time. | | From out of a secure warehouse, a fork-lift | truck loads crates onto an unmarked lorry. | | The crates bear a code-number ED-905. | | Observing, 4 AFOs wait by a pair of unmarked | Armed Response Vehicles (ARVs), led by PS Jane | Cafferty. AFO 1, 2 and 3 are male - PC Kevin | Greysham, PC Ray Randhawa, PC Carl Waldhouse. | | Cafferty eyes the crates tensely as they go into | the lorry. | | CONTROL (O.S.) | (Out of radio. Male) | Charlie Zulu Five Five, sit rep. | | CAFFERTY | (Into radio.) | Charlie Zulu Five Five, loading up, | five minutes to depart. | | CONTROL (O.S.) | (Out of radio.) | Received, Five Five. | | Fully loaded, the lorry shutter is pulled down. | | 10:00:23 CUT TO BLACK: | | 10:00:23 SUPER CAPTION: STEPHEN GRAHAM | | CUT TO: | 1 10:00:25 EXT. EASTFIELD DEPOT. MOMENTS LATER. | | CONTROL (O.S.) | (Out of radio.) | Control, Charlie Zulu Five Five. | Please confirm enclosure secured | and you’re ready to go to State 5. | | Cafferty gives the Lorry Driver (in his cabin) a | nod. -

December 2020 Church Bell

St. John’s Lutheran Church December 2020 Church Bell From the Desk of Pastor Clark “I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full.” - John 10:10 In just a few weeks, we will be celebrating the coming of God’s own Son to this world. Why did Jesus come? He came to fulfill prophecy. He came in obedience to the Father. He came to testify to the Truth. But, most of all, He came because He loves us and wanted us to experience life to the full! This life is intended to be a fulfilling gift from our Maker. Unfortunately, too many people never experience it that way. Things like worry, bitterness, illness, fear, bad decisions, and a sense of meaninglessness make this life seem less like a gift and more like a daily grind. Jesus’ life and death dealt in full with all those things so that we might get that abundant life back. (Continued on pg. 3) 1 St. John’s Lutheran Church 302 NE 2nd Street Buffalo, MN 55313 Phone: 763-682-1883 Fax: 763-682-1936 Noah’s Ark Preschool: 763-682-1883 [email protected] Sharing a changeless Christ in a changing world. www.stjohnsbuffalo.org Rev. Ryan Clark, Pastor Tim Vergin [email protected] 845-549-0730 Kelly Thole, DCE, Director of [email protected] Family Ministry Kyle Bjork, Head Elder [email protected] Tracey Anderson Bill Elletson Chris Ryan, Vicar, Director of Dave Haggerty Youth Ministry Gabe Licht [email protected] Peter March Katherine Clark, Dir. of Special Ministries, Ryan Rutten Assimilation, Small Groups & Youth Tony Sabraski [email protected] -

September 2020 Church Bell

St. John’s Lutheran Church September 2020 Church Bell From the Desk of Pastor Clark Have you noticed how angry people are today? The vitriol on the news and on social media is maybe beyond anything I have seen in my lifetime. Why is that? Well, 2020 has been a perfect storm for anger, resentment, offense, etc. First of all, the worldwide pandemic has everyone scared and on-edge. Add to that the racial issues. Then, top it all off with a Presidential election, and you have the perfect storm! Beginning the weekend of September 13, we are starting a new sermon series entitled “The Defense against Offense.” Here we are going to be looking at wisdom from the Holy Scriptures about how to avoid getting sucked into the anger, hate, and resentment all around us. We hope you’ll join us for (Continued on pg. 3) 1 St. John’s Lutheran Church 302 NE 2nd Street Buffalo, MN 55313 Phone: 763-682-1883 Fax: 763-682-1936 Noah’s Ark Preschool: 763-682-1883 [email protected] Sharing a changeless Christ in a changing world. www.stjohnsbuffalo.org Rev. Ryan Clark, Pastor Tim Vergin [email protected] 845-549-0730 [email protected] Kelly Thole, DCE, Director of Kyle Bjork, Head Elder Family Ministry Tracey Anderson [email protected] Derek Annis Chris Ryan, Vicar, Director of Gregg Beckman Youth Ministry Bill Elletson Dave Haggerty [email protected] Gabe Licht Katherine Clark, Dir. of Special Ministries, Peter March Assimilation, Small Groups & Youth Ryan Rutten [email protected] Tony Sabraski Beth Peterson-Hane, -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M. -

Download the Press

Presents HERB ALPERT IS… Written and Directed by John Scheinfeld RT: 111 Minutes Publicity Contacts: Falco Ink. | 212-445-7100 Steven Beeman, [email protected] Adrianna Valentin, [email protected] “I think the ups and downs of my life can inspire others.” -Herb Alpert Herb Alpert is a multi-faceted man, a man of many passions. Short Synopsis With his trumpet he turned the Tijuana Brass into gold, earning 15 gold and 14 platinum records; He has won nine Grammys Awards between 1966 and 2014, and received the National Medal of Arts from President Barack Obama in 2012. Herb co-founded the indie label, A & M Records with his business partner, Jerry Moss, which recorded artists as varied as Carole King, Cat Stevens, The Carpenters, Janet Jackson, Peter Frampton, Joe Cocker, Quincy Jones, Sergio Mendes, and The Police. A&M would go on to become one of the most successful independent labels in history. He has shown his striking work as an abstract painter and sculptor, worldwide. And through the Herb Alpert Foundation, he has given significant philanthropic support of educational programs in the arts nationwide, from the Harlem School of the Arts and Los Angeles City College to CalArts and UCLA. John Scheinfeld’s documentary Herb Alpert is… profiles the artist, now 85, mostly from the perspective of colleagues like Questlove, Sting, and Bill Moyers. In their words, the shy, unassuming trumpeter is a musical, artistic and philanthropic heavyweight. Long Synopsis Herb Alpert was a shy third grader when his music appreciation teacher arranged instruments on a table and encouraged her students to experiment. -

Michael Hoppé Featuring the World Premiere of Requiem for Peace & Reconciliation

Michael Hoppé featuring the world premiere of Requiem for Peace & Reconciliation SEDONA ACADEMY OF CHAMBER SINGERS RYAN HOLDER, DIRECTOR TETRA STRING QUARTET . SUNDAY, JUNE 9, 2019 | 2:00PM THE CHURCH OF THE RED ROCKS 54 BOWSTRING DRIVE SEDONA, AZ 86336 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 PROGRAM 4 MEET THE COMPOSER 5 A NOTE FROM THE COMPOSER 6-7 TEXT & TRANSLATION 8-9 ABOUT US 10-14 MEET THE SINGERS 15 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Cover photo generously donated for SACS 2019 by local artist Chuck Claude through CClaude Photography© www.cclaudephotography.com Michael Hoppé featuring the world premiere of Requiem for Peace & Reconciliation SEDONA ACADEMY OF CHAMBER SINGERS Ryan Holder, Founding Artistic Director TETRA STRING QUARTET I. Some Other Time Moon Ghost Waltz Renouncement Michael Hoppé, piano Jenna Dalbey, cello II. The Parting Michael Hoppé, piano Heidi Wright, violin Jenna Dalbey, cello Lincoln’s Lament Jude’s Theme Michael Hoppé, piano Heidi Wright, violin III. Wish You Were Here Beneath Mexican Stars Children’s Waltz Michael Hoppé, piano INTERMISSION IV. Safe to Port (a cappella) I am the Moon (a cappella) Sedona Academy of Chamber Singers V. Requiem for Peace & Reconciliation* Introit Kyrie Sanctus Lacrimosa Pie Jesu Agnus Dei Lux Aeterna In Paradisum *World Premiere 3 MEET THE COMPOSER MICHAEL HOPPÉ Michael Hoppé is a GRAMMY nominated composer with an exceptional melodic talent, and distinctive evocative style. He has an extensive background in both pop and classical music which his recordings reflect. Hoppé’s music is performed and heard internationally including HBO’s “The Sopranos”, Oprah Winfrey Show, Michael Moore’s documentary “Sicko”, David Volach’s “My Father, My Lord”, “Misunderstood” (starring Gene Hackman), and the multi-award winning short “Eyes of the Wind” which reached the Oscar nomination short list. -

Vienna's Best Friends

ViennaViennaandand OaktonOakton Stalled Labor Market Slows County Budget News, Page 3 PetInside Connection Classifieds, Page 14 Classifieds, ❖ Sports, Page 12 ❖ Entertainment, Page 10 ❖ Opinion, Page 6 Vienna’s House Passes Best Friends Keam’s Bill on Pet Connection, Page 8 Food Allergies News, Page 4 From left: Jack O’Dell, Ryan O’Dell, Lauren Meier, Photo contributed Photo proud owner Alex Lanier holding Sandy, a golden retriever. www.ConnectionNewspapers.comFebruary 25 - MArch 3, 2015 onlineVienna/Oakton at www.connectionnewspapers.com Connection ❖ February 25 - March 3, 2015 ❖ 1 Faith Faith Notes are for announcements and Wednesday evenings at 6:30 p.m. for www.havenofnova.org. Rooms are open, every Saturday, 1-5 reading related to Centering Prayer, fol- events in the faith community. Send to anyone wanting encouragement and p.m., at 8200 Bell Lane. A team of Chris- lowed by a 20-minute prayer period. [email protected]. healing through prayers. People are McLean Bible Church Fitness Class tians is available to anyone requesting E-mail Martha Thomas at Deadline is Friday. available to pray with you or for you. at Body & Soul Fitness. Gain balance, prayer. Free and open to the public. 703- [email protected] or call the Antioch Christian Church is located at energy and strength at 9:45 a.m. Mon- 698-9779 or church at 703-759-3509. St. Francis Episcopal Church, 1860 Beulah Road in Vienna. days and Fridays. Free childcare for www.viennachristianhealingrooms.com. 9220 Georgetown Pike in Great Falls, www.antiochdoc.org registered students. The Jewish Federation of offers musical, educational, outreach and [email protected]. -

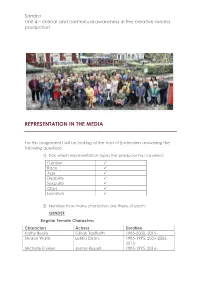

Representation in the Media

Sandra Unit 4 – critical and contextual awareness in the creative media production REPRESENTATION IN THE MEDIA For this assignment I will be looking at the cast of Eastenders answering the following questions: 1) Tick which representation types the producer has covered: Gender Race Age Disability Sexuality Class Location 2) Number how many characters are there of each: GENDER Regular Female Characters Characters Actress Duration Kathy Beale Gillian Taylforth 1985-2000, 2015- Sharon Watts Letitia Dean 1985-1995, 2001-2006, 2012- Michelle Fowler Jenna Russell 1985-1995, 2016- Susan Tully Dot Cotton June Brown 1985-1993, 1997- Sonia Fowler Natalie Cassidy 1993-2007, 2010-2011, 2014- Rebecca Fowler Jasmine Armfield 2000, 2002, 2005-2007, Jade Sharif 2014- Alex and Vicky Gonzalez Louise Mitchell Tilly Keeper 2001-2003, 2008, 2010, Brittany Papple 2016- Danni Bennatar Rachel Cox Jane Beale Laurie Brett 2004-2012, 2014- Stacey Slater Lacey Turner 2004-2012, 2014- Jean Slater Gillian Wright 2004- Honey Mitchell Emma Barton 2005-2008, 2014- Denise Fox Diana Parish 2006- Libby Fox Belinda Owusu 2006-2010, 2014- Abi Branning Lorna Fitzgerald 2006- Lauren Branning Jacqueline Jossa 2006- Madeline Duggan Shirley Carter Linda Henry 2006- Whitney Dean Shona McGarty 2008- Kim Fox Tameka Empson 2009- Glenda Mitchell Glynis Barber 2010-2011, 2016- Tina Carter Luisa Bradshaw-White 2013- Linda Carter Kellie Bright 2013- Donna Yates Lisa Hammond 2014- Carmel Kazemi Bonnie Langford 2015- Madison Drake Seraphina Beh 2017- Alexandra D‘Costa Sydney Craven -

Red Note New Music Festival Program, 2015 School of Music Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Red Note New Music Festival Music 2015 Red Note New Music Festival Program, 2015 School of Music Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/rnf Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation School of Music, "Red Note New Music Festival Program, 2015" (2015). Red Note New Music Festival. 2. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/rnf/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Red Note New Music Festival by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guest Composers & Guest Ensembles ILLINOIS STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC RED NOTE NEW MUSIC FESTIVAL 2015 SUNDAY, MARCH 29 - FRIDAY, APRIL 3 GUEST COMPOSER STEVEN STUCKY GUEST ENSEMBLES MOMENTA QUARTET THE CITY OF TOMORROW CARL SCHIMMEL, DIRECTOR 2 2015 RED NOTE MUSIC FESTIVAL CALENDAR OF EVENTS SUNDAY, MARCH 29TH 7 pm, Center for the Performing Arts Illinois State University Symphony Orchestra and Chamber Orchestra Dr. Glenn Block, conductor Music by Martha Horst, Steven Stucky, and Roger Zare $10.00 General admission, $8.00 Faculty/Staff, $6.00 Students/Seniors MONDAY, MARCH 30TH 8 pm, Kemp Recital Hall The City of Tomorrow Music by John Aylward, Nat Evans, David Lang, Andrew List, and Karlheinz Stockhausen TUESDAY, MARCH 31ST 8 pm, Kemp Recital Hall ISU Faculty and Students, with special guest pianist John Orfe Music of Steven Stucky, as well as the winning piece in the RED NOTE New Music Festival Chamber Composition Competition, push/pull, by Nicholas Omiccioli WEDNESDAY, APRIL 1ST 1 pm, Kemp Recital Hall READING SESSION – The City of Tomorrow Reading Session for ISU Student Composers 8 pm, Kemp Recital Hall The City of Tomorrow & Momenta Quartet A concert of premieres by the participants in the RED NOTE New Music Festival Composition Workshop: Weijun Chen, Viet Cuong, Brian Heim, Jae-Goo Lee, Ryan Lindveit, Carolyn O’Brien, and Corey Rubin.