Florida's Harmful Algal Bloom (HAB) Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinos, Toxins and Fears, Oh My!

Dinos, Toxins and Fears, Oh My! (a new algae adventure… we’re not in Delaware anymore) The Cast of Characters: UD Citizen Monitoring Program- Ed Whereat, Muns Farestad Graham Purchase, Capt. Dick Peoples and the “Spectacle” AG Robbins, and other volunteers. DNREC- Jack Pingree, Glenn King Jr., and DNREC’s HAB Monitoring Program UNCW- Dr, Carmelo Tomas FWRI-Leanne Flewelling and Jennifer Wolny Also, thanks to Bill Winkler Sr., and Dave Munchel (deceased) CIB STAC Nov 16, 2007 “Red Tide” Most “red tides” are caused by dinoflagellates which have a variety of pigments ranging from yellow-red-brown in addition to the green of Chlorophyll, so blooms of some dinoflagellates actually appear as red water. The dinoflagellate, Karenia brevis, is commonly called the “Florida red tide” even though blooms are usually yellow-green. The toxicity of K. brevis is well- documented. Blooms are associated with massive fish kills, shellfish toxicity, marine mammal deaths, and human respiratory irritation if exposed to salt-spray aerosols. There are several newly described species of Karenia, one being K. papilionacea, formerly known as K. brevis “butterfly-type”. Karenia papilionacea, K. brevis, and a few others are commonly found in the Gulf of Mexico, but these and yet other Karenia species are also found throughout the world. This summer, K. papilionacea and K. brevis were detected in Delaware waters. The potential for toxicity in K. papilionacea is low, but less is known about the newly described species. Blooms of K. brevis have migrated to the Atlantic by entrainment in Gulf Stream waters. Occasional blooms have been seen along the Atlantic coast of Florida since 1972. -

Molecular Data and the Evolutionary History of Dinoflagellates by Juan Fernando Saldarriaga Echavarria Diplom, Ruprecht-Karls-Un

Molecular data and the evolutionary history of dinoflagellates by Juan Fernando Saldarriaga Echavarria Diplom, Ruprecht-Karls-Universitat Heidelberg, 1993 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Botany We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA November 2003 © Juan Fernando Saldarriaga Echavarria, 2003 ABSTRACT New sequences of ribosomal and protein genes were combined with available morphological and paleontological data to produce a phylogenetic framework for dinoflagellates. The evolutionary history of some of the major morphological features of the group was then investigated in the light of that framework. Phylogenetic trees of dinoflagellates based on the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene (SSU) are generally poorly resolved but include many well- supported clades, and while combined analyses of SSU and LSU (large subunit ribosomal RNA) improve the support for several nodes, they are still generally unsatisfactory. Protein-gene based trees lack the degree of species representation necessary for meaningful in-group phylogenetic analyses, but do provide important insights to the phylogenetic position of dinoflagellates as a whole and on the identity of their close relatives. Molecular data agree with paleontology in suggesting an early evolutionary radiation of the group, but whereas paleontological data include only taxa with fossilizable cysts, the new data examined here establish that this radiation event included all dinokaryotic lineages, including athecate forms. Plastids were lost and replaced many times in dinoflagellates, a situation entirely unique for this group. Histones could well have been lost earlier in the lineage than previously assumed. -

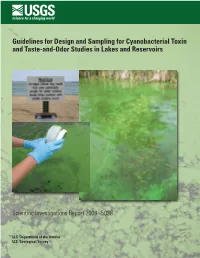

Guidelines for Design and Sampling for Cyanobacterial Toxin and Taste-And-Odor Studies in Lakes and Reservoirs

Guidelines for Design and Sampling for Cyanobacterial Toxin and Taste-and-Odor Studies in Lakes and Reservoirs Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5038 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Photo 1 Photo 3 Photo 2 Front cover. Photograph 1: Beach sign warning of the presence of a cyanobacterial bloom, June 29, 2006 (photograph taken by Jennifer L. Graham, U.S. Geological Survey). Photograph 2: Sampling a near-shore accumulation of Microcystis, August 8, 2006 (photograph taken by Jennifer L. Graham, U.S. Geological Survey). Photograph 3: Mixed bloom of Anabaena, Aphanizomenon, and Microcystis, August 10, 2006 (photograph taken by Jennifer L. Graham, U.S. Geological Survey). Background photograph: Near-shore accumulation of Microcystis, August 8, 2006 (photograph taken by Jennifer L. Graham, U.S. Geological Survey). Guidelines for Design and Sampling for Cyanobacterial Toxin and Taste-and-Odor Studies in Lakes and Reservoirs By Jennifer L. Graham, Keith A. Loftin, Andrew C. Ziegler, and Michael T. Meyer Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5038 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Influence of Environmental Parameters on Karenia Selliformis Toxin Content in Culture

Cah. Biol. Mar. (2009) 50 : 333-342 Influence of environmental parameters on Karenia selliformis toxin content in culture Amel MEDHIOUB1, Walid MEDHIOUB3,2, Zouher AMZIL2, Manoella SIBAT2, Michèle BARDOUIL2, Idriss BEN NEILA3, Salah MEZGHANI3, Asma HAMZA1 and Patrick LASSUS2 (1) INSTM, Institut National des Sciences et Technologies de la Mer. Laboratoire d'Aquaculture, 28, rue 2 Mars 1934, 2025 Salammbo, Tunisie. E-mail: [email protected] (2) IFREMER, Département Environnement, Microbiologie et Phycotoxines, BP 21105, 44311 Nantes, France. (3) IRVT, Institut de la Recherche Vétérinaire de Tunisie, centre régional de Sfax. Route de l'aéroport, km 1, 3003 Sfax, Tunisie Abstract: Karenia selliformis strain GM94GAB was isolated in 1994 from the north of Sfax, Gabès gulf, Tunisia. This species, which produces gymnodimine (GYM) a cyclic imine, has since been responsible for chronic contamination of Tunisian clams. A study was made by culturing the microalgae on enriched Guillard f/2 medium. The influence of growing conditions on toxin content was studied, examining the effects of (i) different culture volumes (0.25 to 40 litre flasks), (ii) two temperature ranges (17-15°C et 20-21°C) and (iii) two salinities (36 and 44). Chemical analyses were made by mass spectrometry coupled with liquid chromatography (LC-MS/MS). Results showed that (i) the highest growth rate (0.34 ± 0.14 div d-1) was obtained at 20°C and a salinity of 36, (ii) GYM content expressed as pg eq GYM cell-1 increased with culture time. The neurotoxicity of K. selliformis extracts was confirmed by mouse bioassay. This study allowed us to cal- culate the minimal lethal dose (MLD) of gymnodimine (GYM) that kills a mouse, as a function of the number of K. -

Development of a Quantitative PCR Assay for the Detection And

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/544247; this version posted February 8, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Development of a quantitative PCR assay for the detection and enumeration of a potentially ciguatoxin-producing dinoflagellate, Gambierdiscus lapillus (Gonyaulacales, Dinophyceae). Key words:Ciguatera fish poisoning, Gambierdiscus lapillus, Quantitative PCR assay, Great Barrier Reef Kretzschmar, A.L.1,2, Verma, A.1, Kohli, G.S.1,3, Murray, S.A.1 1Climate Change Cluster (C3), University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, 2007 NSW, Australia 2ithree institute (i3), University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, 2007 NSW, Australia, [email protected] 3Alfred Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum fr Polar- und Meeresforschung, Am Handelshafen 12, 27570, Bremerhaven, Germany Abstract Ciguatera fish poisoning is an illness contracted through the ingestion of seafood containing ciguatoxins. It is prevalent in tropical regions worldwide, including in Australia. Ciguatoxins are produced by some species of Gambierdiscus. Therefore, screening of Gambierdiscus species identification through quantitative PCR (qPCR), along with the determination of species toxicity, can be useful in monitoring potential ciguatera risk in these regions. In Australia, the identity, distribution and abundance of ciguatoxin producing Gambierdiscus spp. is largely unknown. In this study we developed a rapid qPCR assay to quantify the presence and abundance of Gambierdiscus lapillus, a likely ciguatoxic species. We assessed the specificity and efficiency of the qPCR assay. The assay was tested on 25 environmental samples from the Heron Island reef in the southern Great Barrier Reef, a ciguatera endemic region, in triplicate to determine the presence and patchiness of these species across samples from Chnoospora sp., Padina sp. -

Mote Marine Laboratory Red Tide Studies

MOTE MARINE LABORATORY RED TIDE STUDIES FINAL REPORT FL DEP Contract MR 042 July 11, 1994 - June 30, 1995 Submitted To: Dr. Karen Steidinger Florida Marine Research Institute FL DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION 100 Eighth Street South East St. Petersburg, FL 33701-3093 Submitted By: Dr. Richard H. Pierce Director of Research MOTE MARINE LABORATORY 1600 Thompson Parkway Sarasota, FL 34236 Mote Marine Laboratory Technical Report No. 429 June 20, 1995 This document is printed on recycled paper Suggested reference Pierce RH. 1995. Mote Marine Red Tide Studies July 11, 1994 - June 30, 1995. Florida Department of Environmental Pro- tection. Contract no MR 042. Mote Marine Lab- oratory Technical Report no 429. 64 p. Available from: Mote Marine Laboratory Library. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. SUMMARY. 1 II. CULTURE MAINTENANCE AND GROWTH STUDIES . 1 Ill. ECOLOGICAL INTERACTION STUDIES . 2 A. Brevetoxin Ingestion in Black Seabass B. Evaluation of Food Carriers C. First Long Term (14 Day) Clam Exposure With Depuration (2/6/95) D. Second Long Term (14 Day) Clam Exposure (3/21/95) IV. RED TIDE FIELD STUDIES . 24 A. 1994 Red Tide Bloom (9/16/94 - 1/4/95) B. Red Tide Bloom (4/13/94 - 6/16/95) C. Red Tide Pigment D. Bacteriological Studies E. Brevetoxin Analysis in Marine Organisms Exposed to Sublethal Levels of the 1994 Natural Red Tide Bloom V. REFERENCES . 61 Tables Table 1. Monthly Combined Production and Use of Laboratory C. breve Culture. ....... 2 Table 2. Brevetoxin Concentration in Brevetoxin Spiked Shrimp and in Black Seabass Muscle Tissue and Digestive Tract Following Ingestion of the Shrimp ............... -

Cyanobacterial Toxins: Saxitoxins

WHO/SDE/WSH/xxxxx English only Cyanobacterial toxins: Saxitoxins Background document for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality and Guidelines for Safe Recreational Water Environments Version for Public Review Nov 2019 © World Health Organization 20XX Preface Information on cyanobacterial toxins, including saxitoxins, is comprehensively reviewed in a recent volume to be published by the World Health Organization, “Toxic Cyanobacteria in Water” (TCiW; Chorus & Welker, in press). This covers chemical properties of the toxins and information on the cyanobacteria producing them as well as guidance on assessing the risks of their occurrence, monitoring and management. In contrast, this background document focuses on reviewing the toxicological information available for guideline value derivation and the considerations for deriving the guideline values for saxitoxin in water. Sections 1-3 and 8 are largely summaries of respective chapters in TCiW and references to original studies can be found therein. To be written by WHO Secretariat Acknowledgements To be written by WHO Secretariat 5 Abbreviations used in text ARfD Acute Reference Dose bw body weight C Volume of drinking water assumed to be consumed daily by an adult GTX Gonyautoxin i.p. intraperitoneal i.v. intravenous LOAEL Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level neoSTX Neosaxitoxin NOAEL No Observed Adverse Effect Level P Proportion of exposure assumed to be due to drinking water PSP Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning PST paralytic shellfish toxin STX saxitoxin STXOL saxitoxinol -

Save the Reef

Save the Reef A member group of Lock the Gate Alliance www.savethereef.net.au Committee Secretary Senate Standing Committees on Environment and Communications PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Phone: +61 2 6277 3526 Fax: +61 2 6277 5818 [email protected] Submission to the Senate Inquiry on The adequacy of the Australian and Queensland Governments’ efforts to stop the rapid decline of the Great Barrier Reef, including but not limited to: Points a–k. Save the Reef would like to thank this committee for the opportunity to make a submission and would also like to speak further if there is an opportunity at any public hearings. The Great Barrier Reef is Australia’s greatest natural asset. It is a tourism mecca, a 6 billion dollar economic boon as well as a scientific wonderland. It is a World Heritage Listed property and an acknowledged world wonder. The Great Barrier Reef is part of Australia’s very identity. We are failing to protect the Great Barrier Reef. The efforts to stop the rapid decline of the Great Barrier Reef are grossly inadequate. It demonstrates that our current system for protecting the environment is broken. Environmental impact statements, conditions, offsets, regulations, enforcement and even the EPBC act, processes meant to protect the environment are being subverted and the impact is apparent. The holes in the “Swiss Cheese” are lining up and have allowed and are continuing to allow further destruction of the Great Barrier Reef when it needs our protection the most. The recent developments in Gladstone are a clear demonstration of the failure of our systems. -

Ciguatera: Current Concepts

Ciguatera: Current concepts DAVID Z. LEVINE, DO Ciguatera poisoning develops unraveling the diagnosis may prove difficult. after ingestion of certain coral reef-asso Although the syndrome has been known for at ciated fish. With travel to and from the least hundreds of years, its mechanisms are tropics and importation of tropical food only beginning to be elucidated. Effective treat fish increasing, ciguatera has begun to ments have just begun to emerge. appear in temperate countries with more Ciguatera is a major public health prob frequency. The causative agents are cer lem in the tropics, with probably more than tain varieties of the protozoan dinofla 30,000 poisonings yearly in Puerto Rico and gellate Gambierdiscus toxicus, but bacte the US Virgin Islands alone. The endemic area ria associated with these protozoa may is bounded by latitudes 37° north and south. have a role in toxin elaboration. A specif Ciguatera in temperate countries is a concern ic "ciguatoxin" seems to cause the symptoms, because people returning from business trips, but toxicosis may also be a result of a fam vacations, or living in the tropics may have ily of toxins. Toxicosis develops from 10 been poisoned through food they had eaten. minutes to 30 hours after ingestion of poi The development of worldwide marketing of soned fish, and the syndrome can include fish from a variety of ecosystems creates a dan gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms, ger of ciguatera intoxication in climates far as well as chills, sweating, pruritus, brady removed from sandy beaches and waving·palms. cardia, tachycardia, and long-lasting weak Outbreaks have been reported in Vermont, ness and fatigue. -

Assessing the Potential for Range Expansion of the Red Tide Algae Karenia Brevis

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks All HCAS Student Capstones, Theses, and Dissertations HCAS Student Theses and Dissertations 8-7-2020 Assessing the Potential for Range Expansion of the Red Tide Algae Karenia brevis Edward W. Young Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/hcas_etd_all Part of the Marine Biology Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Edward W. Young. 2020. Assessing the Potential for Range Expansion of the Red Tide Algae Karenia brevis. Capstone. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, . (13) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/hcas_etd_all/13. This Capstone is brought to you by the HCAS Student Theses and Dissertations at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in All HCAS Student Capstones, Theses, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Capstone of Edward W. Young Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Marine Science Nova Southeastern University Halmos College of Arts and Sciences August 2020 Approved: Capstone Committee Major Professor: D. Abigail Renegar, Ph.D. Committee Member: Robert Smith, Ph.D. This capstone is available at NSUWorks: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/hcas_etd_all/13 Nova Southeastern Univeristy Halmos College of Arts and Sciences Assessing the Potential for Range Expansion of the Red Tide Algae Karenia brevis By Edward William Young Submitted to the Faculty of Halmos College of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science with a specialty in: Marine Biology Nova Southeastern University September 8th, 2020 1 Table of Contents 1. -

Sample Chapter Algal Blooms

ALGAL BLOOMS 7 Observations and Remote Sensing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ energy and material transport through the food web, and JSTARS.2013.2265255. they also play an important role in the vertical flux of Pack, R. T., Brooks, V., Young, J., Vilaca, N., Vatslid, S., Rindle, P., material out of the surface waters. These blooms are Kurz, S., Parrish, C. E., Craig, R., and Smith, P. W., 2012. An “ ” overview of ALS technology. In Renslow, M. S. (ed.), Manual distinguished from those that are deemed harmful. of Airborne Topographic Lidar. Bethesda: ASPRS Press. Algae form harmful algal blooms, or HABs, when either Sithole, G., and Vosselman, G., 2004. Experimental comparison of they accumulate in massive amounts that alone cause filter algorithms for bare-Earth extraction from airborne laser harm to the ecosystem or the composition of the algal scanning point clouds. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and community shifts to species that make compounds Remote Sensing, 59,85–101. (including toxins) that disrupt the normal food web or to Shan, J., and Toth, C., 2009. Topographic Laser Ranging and Scanning: Principles and Processes. Boca Raton: CRC Press. species that can harm human consumers (Glibert and Slatton, K. C., Carter, W. E., Shrestha, R. L., and Dietrich, W., 2007. Pitcher, 2001). HABs are a broad and pervasive problem, Airborne laser swath mapping: achieving the resolution and affecting estuaries, coasts, and freshwaters throughout the accuracy required for geosurficial research. Geophysical world, with effects on ecosystems and human health, and Research Letters, 34,1–5. on economies, when these events occur. This entry Wehr, A., and Lohr, U., 1999. -

Morphology, Molecular Phylogeny and Toxinology of Coolia And

Botanica Marina 2019; 62(2): 125–140 Maria Cristina de Queiroz Mendes*, José Marcos de Castro Nunes, Santiago Fraga, Francisco Rodríguez, José Mariano Franco, Pilar Riobó, Suema Branco and Mariângela Menezes Morphology, molecular phylogeny and toxinology of Coolia and Prorocentrum strains isolated from the tropical South Western Atlantic Ocean https://doi.org/10.1515/bot-2018-0053 P. emarginatum by mass spectrometry analyses. However, Received 19 May, 2018; accepted 14 February, 2019; online first hemolytic assays in P. emarginatum and both Coolia strains 13 March, 2019 in this study showed positive results. Abstract: The morphology, molecular phylogeny and toxi- Keywords: Coolia malayensis; Coolia tropicalis; hemolytic nology of two Coolia and one Prorocentrum dinoflagellate assay; LC-HRMS; Prorocentrum emarginatum. strains from Brazil were characterized. They matched with Coolia malayensis and Coolia tropicalis morphotypes, while the Prorocentrum strain fitted well with the morphology of Prorocentrum emarginatum. Complementary identification Introduction by molecular analyses was carried out based on LSU and ITS-5.8S rDNA. Phylogenetic analyses of Coolia strains (D1/ Epibenthic dinoflagellate communities harbor potentially D2 region, LSU rDNA), showed that C. malayensis (strain harmful species that attracted great interest in the last UFBA044) segregated together with sequences of this spe- decades due to their apparent expansion from tropical/ cies from other parts of the world, but diverged earlier in subtropical areas to temperate