European Union Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) Introduction Guide

Intelligent Transport Systems ( ( ) ITS Intelligent Transport Systems ITS ) Introduction Guide Introduction Guide Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) Introduction Guide PREFACE Lately, a number of countries in Asia Pacific Region have been developing road infrastructure rapidly. Meanwhile, rapid economic growth and population concentration in urban areas have caused urban traffic problems such as congestion, accidents, and environmental problems that became serious in developing countries as well as in developed countries. In such circumstances, several countries are making attempt to resolve such traffic problems using Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS), some of them showing significant improvement. In order to introduce and advance ITS in countries, it is critical to share common perceptions of knowledge/expertise in the following aspects: 1) how to employ ITS effectively in order to resolve urban traffic issues, 2) how to integrate information technologies and transport infrastructure, and 3) how to build a platform for ITS to perform properly. Given such environment, Asian Civil Engineering Coordinating Council (ACECC) approved the establishment of the Technical Committee for the theme of “ITS-based Solutions for Urban Traffic Problems in Asia Pacific Countries (TC-16),” proposed by the Japan Society of Civil Engineers (JSCE) at the Technical Committee Coordination Meeting in Tokyo, on March 1, 2012. The TC-16 consists of ten members from eight countries: Japan, Korea, Thailand, Taiwan, Australia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and the United States. Since its establishment, we have collected examples of ITS-based solutions using state-of-the-art Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) for aforementioned common issues in Asian countries, and encouraged discussion on approaches of ITS introduction according to country’s level of economic growth and national land development. -

Intelligent Transportation Systems

EXPLAINING INTERNATIONAL IT APPLICATION LeADERSHIP: Intelligent Transportation Systems Stephen Ezell | January 2010 Explaining International IT Application Leaderhip: Intelligent Transportation Systems Stephen Ezell ITIF The Information Technology & Innovation Foundation January 2010 THE INFORMAtiON TECHNOLOGY & INNOVAtiON FOUNDAtiON Executive Summary: Intelligent Transportation Systems nformation technology (IT) has transformed many industries, from education to health care to government, and is now in the Information technolog y early stages of transforming transportation systems. While many (IT) has transformed I think improving a country’s transportation system solely means build- many industries, from education to health care ing new roads or repairing aging infrastructures, the future of trans- to government, and is portation lies not only in concrete and steel, but also increasingly in now in the early stages using IT. IT enables elements within the transportation system—vehi- of transforming cles, roads, traffic lights, message signs, etc.—to become intelligent by transportation systems. embedding them with microchips and sensors and empowering them to communicate with each other through wireless technologies. In the leading nations in the world, ITS bring significant improvement in transportation system performance, including reduced congestion and increased safety and traveler convenience. Unfortunately, the United States lags the global leaders, particularly Japan, Singapore, and South Korea in ITS deployment. For the most part, this has been the result of two key factors: a continued lack of adequate funding for ITS and the lack of the right organizational system to drive ITS in the United States, particularly the lack of a federally led approach, as opposed to the “every state on its own approach” that has prevailed to date. -

List of Participating Countries in Horizon Europe

EU Grants: List of participating countries (HE): V1.1 – 19.07.2021 List of Participating Countries in Horizon Europe Third countries associated to Horizon Europe Association to Horizon Europe is governed by the Horizon Europe Regulation 2021/6951. Legal entities from Associated Countries can participate under equivalent conditions as legal entities from the EU Member States, unless specific limitations or conditions are laid down in the work programme and/or call/topic text. Such measures could include the limitation of participation in certain actions to legal entities established in the EU alone, or in the EU and specified non-EU countries, in order to safeguard the EU’s strategic assets, interests, autonomy or security. Limitations or conditions may also be attached to the participation of legal entities established in an eligible country but which are controlled directly or indirectly by an ineligible country2. The eligibility will be clearly defined in the work programme. There could also be criteria on the place of establishment of the legal entity to take into account specific policy requirements or the nature and objectives of the action3. All sixteen non-EU countries associated to the previous programme, Horizon 2020, have also expressed interest to become associated to Horizon Europe. Other third countries have also expressed an interest in association. Until association agreements start producing legal effects either through provisional application or their entry into force, the transitional arrangement set out in the General Annexes to the Horizon Europe Work Programme 2021-2022 is applicable (for the entire Programme, including ERC, EIC, EIT and the institutionalised European partnerships4) with regard to the following countries and legal entities established in these countries, with which association negotiations are being processed or where association is imminent (listed in the alphabetical order): 1. -

Intelligent Transport Systems

INTELLIGENT TRANSPORT SYSTEMS Reference Material for COMPETENCE funded within the STEER Program of the EU The sole responsibility for the content of this [webpage, publication etc.] lies with the authors. It does not represent the opinion of the Community. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. For the use of the following material: The aim of this material is to strengthen the knowledge of local / regional managing agencies in the transport field and to accelerate the take up of EU research results in the field of local and regional transport. The beneficiaries of the project are managing (energy) agencies who want to play a bigger role in the transport field. Due to the size and (in some cases) the number of individual projects, it is not possible to explain each single result in detail and include it into these written materials. The following set of material should rather act as a portal and facilitate the access of single projects and detailed results. Therefore the material in hand doesn't lay claim to completeness. The following compendium contains results of EU research-projects and complementary results of national research-projects. The authors thank the partners and collaborators of the COST 342 project. A complete list of the projects, consortia, and cited literature is given at the end of the material. The material for the topic “Intelligent Transport Systems” was compiled by Tom RYE (Napier University, Edinburgh) for the STEER training project COMPETENCE in 2006. Intelligent Transport Systems 1 Reference Material from COMPETENCE / TREATISE / E-ATOMIUM Table of Contents 1. -

(1997 Edition) STANDARDS SETTING in the EUROPEAN UNION

NIST Special Publication 891 (1997 Edition) STANDARDS SETTING IN THE EUROPEAN UNION--- Standards Organizations and Officials in EU Standards Activities Roger A. Rensberger A joint publication of the U.S. Mission to the Standards Specialist European Union, the Commercial Service, Office of Standards Services, NIST and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce Rene van de Zande Senior Commercial Specialist, USEU Helen Delaney The Honorable A. Vernon Weaver Commercial Attache, Standards, USEU United States Representative to the European Union February 1997 U.S. Department of Commerce William M. Daley, Secretary International Trade Administration Ambassador Stuart E. Eizenstat Under Secretary for International Trade U.S. and Foreign Commercial Service Lauri Fitz-Pegado, Director General Technology Administration Mary L. Good, Under Secretary for Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology Arati Prabhakar, Director In April 1995, when European Commission Vice President Sir Leon Brittan, Commissioner Martin Bangemann, and the late U.S. Secretary of Commerce Ronald H. Brown jointly asked more than 1,400 U.S. and European businesses and associations how the Commission and the U.S. Administration could improve and deepen the transatlantic business relationship, the issue area cited most often by far was standards. I am pleased that the Commercial Service at the U.S. Mission to the European Union prepared a guide that will be an important resource for U.S. manufacturers and exporters seeking information on standards in the EU, on key EU standards developing organizations and officials in the Commission with standards responsibilities. The purpose of the guide, Standards Setting in the European Union, is to bring U.S. -

How the European Union Works

THE EUROPEAN UNION EXPLAINED How the European Union works Your guide to the EU institutions COM-12-020_MEP_EN5.indd cov1 31/10/12 11:28 THE EUROPEAN UNION EXPLAINED This publication is a part of a series that explains what the EU does in diff erent policy areas, why the EU is involved and what the results are. You can see online which ones are available and download them: europa.eu/pol/index_en.htm How the European Union works Europe 2020 — Europe’s growth strategy The Founding Fathers of the European Union Agriculture Budget Climate action The European Union explained — Competition How the European Union works Consumers Customs European Commission Culture, audiovisual, sport Directorate-General for Communication Development and cooperation Publications Digital agenda 1049 Brussels Economic and monetary union and the euro BELGIUM Education, training, youth Employment and social aff airs Manuscript completed in July 2012 Energy Enlargement Cover: © Luis Pedrosa Enterprise Environment 40 pp. — 21 × 29.7 cm Foreign aff airs and security policy ISBN 978-92-79-25553-3 Fight against fraud doi:10.2775/87270 Fisheries and maritime aff airs Food safety Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, Humanitarian aid 2012 Internal market Justice, citizenship, fundamental rights © European Union, 2012 Migration and asylum Reproduction is authorised. For any use or reproduction Public health of individual photos, permission must be sought directly Regional policy from the copyright holders. Research and innovation Security and home aff airs Printed -

A Guide to Corporate Governance Practices in the European Union

A Guide to Corporate Governance Practices in the European Union in the European Practices Governance A Guide to Corporate A Guide to Corporate Governance Practices in the European Union CONFÉDÉRATION EUROPÉENNE DES ASSOCIATIONS D’ADMINISTRATEURS EUROPEAN CONFEDERATION OF DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATIONS A Guide to Corporate Governance Practices in the European Union © Copyright 2015, All rights reserved. International Finance Corporation 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20433 The conclusions and judgments contained in this report should not be attributed to, and do not necessarily represent the views of, IFC or its Board of Directors or the World Bank or its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent. IFC and the World Bank do not guarantee the accuracy of the data in this publication and accept no responsibility for any conse- quences of their use. The material in this work is protected by copyright. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work may be a violation of applicable law. The International Finance Corporation encourages dissemination of its work and hereby grants permission to users of this work to copy portions for their personal, noncommercial use, without any right to resell, redistribute, or create derivative works there from. Any other copying or use of this work requires the express written permission of the International Finance Corporation.For permission to photocopy or reprint, please send a request with complete information to: The International Finance Corporation c/o the World Bank Permissions -

Intelligent Transportation Systems Report for Mobile GSMA Connected Living Programme

Intelligent Transportation Systems Report for Mobile GSMA Connected Living Programme Copyright © 2015 GSM Association Intelligent Transportation Systems Report for Mobile 1 Contents 0. Executive Summary 5 0.1 Intelligent Transportation Systems 5 0.2 Standards, communications and cloud-based computing in ITS 5 0.3 Intelligent Mobility and Cooperative ITS 5 0.4 Enforcement and security 5 0.5 Fleet Management, Pay As You Drive Insurance & Parking 6 0.6 Road Pricing 6 0.7 Public Transport/Transit 7 0.8 Travel information and Trac management 7 0.9 Smart cities and the Internet of Things (IOT) 8 0.10 Conclusions and recommendations 9 1. Introduction to Intelligent Transportation Systems 11 1.1 Intelligent Transportation Systems 11 1.1.1 Intelligent Mobility 11 1.1.2 Telematics 12 1.2 A brief history of ITS 12 1.3 ITS markets and prospects 13 1.4 The European Commission’s ITS Action Plan and Directive 14 1.4.1 eCall 15 2. Standards, communications and cloud-based computing in ITS 17 2.1 Short-range communications 17 2.1.1 CEN DSRC 5.8 GHz 17 2.1.2 US DSRC 5.9 GHz - WAVE 18 2.2 Wide area communications 19 2.2.1 Broadcast communications 19 2.2.2 Cellular radio in ITS 19 2.3 Smart phones 20 2.4 Cloud-based computing 21 3. Intelligent Mobility and C-ITS 23 3.1 Cooperative ITS 23 3.2 The connected car and autonomous vehicles 24 3.2.1 The connected car 24 3.2.2 Driver support and Intelligent Speed Adaptation (ISA) 25 3.2.3 Autonomous vehicles and self-driving cars 26 3.2.4 NHTSA five levels of vehicle automation 27 4. -

The European Union: Questions and Answers

The European Union: Questions and Answers Updated January 22, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RS21372 SUMMARY RS21372 The European Union: Questions and Answers January 22, 2021 The European Union (EU) is a political and economic partnership that represents a unique form of cooperation among sovereign countries. The EU is the latest stage in a process of integration Kristin Archick begun after World War II, initially by six Western European countries, to foster interdependence Specialist in European and make another war in Europe unthinkable. The EU currently consists of 27 member states, Affairs including most of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, and has helped to promote peace, stability, and economic prosperity throughout the European continent. How the EU Works The EU has been built through a series of binding treaties. Over the years, EU member states have harmonized laws and adopted common policies on an increasing number of economic, social, and political issues. EU members share a customs union; a single market in which capital, goods, services, and people move freely; a common trade policy; and a common agricultural policy. Nineteen EU member states use a common currency (the euro), and 22 members participate in the Schengen area of free movement in which internal border controls have been eliminated. In addition, the EU has been developing a Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), which includes a Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP), and pursuing cooperation in the area of Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) to forge common internal security measures. Member states work together through several EU institutions to set policy and to promote their collective interests. -

H2020 Eligible Countries

HORIZON 2020 – WORK PROGRAMME 2018-2020 General Annexes A. List of countries eligible for funding 1. Legal entities established in the following countries and territories will be eligible to receive funding through Horizon 2020 grants: The Member States (MS) of the European Union (EU), including their outermost regions; The Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT) linked to the Member States1: Anguilla, Aruba, Bermuda, British Antarctic Territory, British Indian Ocean Territory, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Falkland Islands, French Polynesia, French Southern and Antarctic Territories, Greenland, Montserrat, Netherlands Antilles (Bonaire, Curaçao, Saba, Sint Eustatius, Sint Maarten), New Caledonia and Dependencies, Pitcairn, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Helena, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands,Turks and Caicos Islands, Wallis and Futuna Islands. The associated countries (AC): the latest information on which countries are associated, or in the process of association to Horizon 2020 can be found in the online manual2. The following countries, except where this is explicitly excluded in the call text3: Afghanistan, Algeria, American Samoa, Angola, Argentina, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belize, Benin, Bhutan, Bolivia, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Chile, Colombia, Comoros, Congo (Democratic People’s Republic), Congo (Republic), Costa Rica, Côte d’Ivoire, Cuba, Djibouti, Democratic People's Republic of Korea ,Dominica, Dominican -

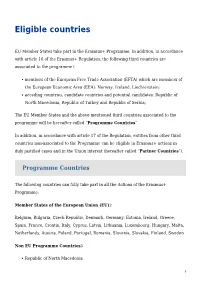

Eligible Countries

Eligible countries EU Member States take part in the Erasmus+ Programme. In addition, in accordance with article 16 of the Erasmus+ Regulation, the following third countries are associated to the programme1: members of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) which are members of the European Economic Area (EEA): Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein; acceding countries, candidate countries and potential candidates: Republic of North Macedonia, Republic of Turkey and Republic of Serbia; The EU Member States and the above mentioned third countries associated to the programme will be hereafter called “Programme Countries”. In addition, in accordance with article 17 of the Regulation, entities from other third countries non-associated to the Programme can be eligible in Erasmus+ actions in duly justified cases and in the Union interest (hereafter called “Partner Countries”). Programme Countries The following countries can fully take part in all the Actions of the Erasmus+ Programme: Member States of the European Union (EU)2 Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden Non EU Programme Countries3 Republic of North Macedonia 1 Erasmus+ Programme Guide Serbia Iceland Liechtenstein Norway Turkey Partner Countries The following countries can take part in certain Actions of the Programme, subject to specific criteria or conditions (for more information, please consult Part B of this Guide). Funding will be allocated to organisations in the countries within their territories as recognised by international law. Applicants and participants must respect any restrictions placed on EU external assistance imposed by the European Council. -

Intelligent Transportation Systems in Europe and Japan

INTERNATIONAL TECHNOLOGY SCANNING PROGRAM SAFETY APPLICATIONS OF Intelligent Transportation Systems in Europe and Japan SPONSORED BY: U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration IN COOPERATION WITH: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials National Cooperative Highway Research Program JANUARY 2006 NOTICE The Federal Highway Administration provides high-quality information to serve Government, industry, and the public in a manner that pro- motes public understanding. Standards and poli- cies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. FHWA periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA-PL-06-001 4. Title and Subtitle Safety Applications of Intelligent Transportation Systems 5. Report Date in Europe and Japan January 2006 7. Author(s) 6. Performing Organization Code John Njord, Dr. Joseph Peters, Michael Freitas, Bruce Warner, 8. Performing Organization Report No. K. Craig Allred, Dr. Robert Bertini, Robert Bryant, Robert Callan, Martin Knopp, Lyle Knowlton, Carlos Lopez, Tom Warne 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) American Trade Initiatives P.O. Box 8228 Alexandria, VA 22306-8228 11. Contract or Grant No. DTFH61-99-C-005 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Office of International Programs Office of Policy Federal Highway Administration U.S. Department of Transportation American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials 14. Sponsoring Agency Code National Cooperative Highway Research Program 15. Supplementary Notes FHWA COTR: Hana Maier, Office of International Programs 16.