The Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma Through Distributed, Mediated Visions of Memory in 2Nd Generation Canadian Chinese Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSH HOUR Missione Parigi

presenta una produzione Arthur Sarkissian e Roger Birnbaum Jackie Chan Chris Tucker in RUSH HOUR Missione Parigi un film di Brett Ratner uscita 5 ottobre 2007 Ufficio Stampa KEY FILMS Georgette Ranucci (+39 335 5943393 [email protected]) Alessandra Tieri (+39 335 8480787 [email protected]) CAST ARTISTICO Carter Chris Tucker Lee Jackie Chan Reynard Max Von Sydow Kenji Hiroyuki Sanada George Yvan Attal Jasmine Youki Kudoh Geneviève Noemie Lenoir Soo Yung Zhang Jingchu Albasciatore Han Tzi Ma Sorella Agnes Dana Ivey Maestro Yu Henry O. Masha Mia Tyler Delegato cinese Michael Chow Delegato britannico David Niven, JR Me Oanh Nguyen Ragazzo del kung fu Andrei Quang Gigante cinese Sun Ming Ming Infermiera Lisa Thornhill Killer francese M. Kentaro Poiliziotti francesi Ludovic Paris Richard Dieux Olivier Schneider Croupier Daniel Yabut Barman Frank Bruynbroek Moglie di George Julie Depardieu Ispettore Revi Roman Polanski credits not contractual CAST TECNICO Diretto da Brett Ratner Scritto da Jeff Nathanson Ispirato ai personaggi creati da Ross LaManna Direttore della fotografia J. Michael Muro Effetti speciali John Bruno Musiche Lalo Schifrin Costumi Betsy Heimann Montaggio Don Zimmerman, A.C.E. Dean Zimmerman Mark Helfrich, A.C.E. Scenografie Edward Verreaux Casting Ronna Kress, C.S.A. Co-Produttori James M. Freitag Leon Dudevoir Produttore esecutivo Toby Emmerich Prodotto da Arthur Sarkissian Roger Birnbaum Prodotto da Jay Stern Jonathan Glickman Andrew Z. Davis RUSH HOUR - Missione Parigi Nel cuore di Parigi si nasconde un segreto mortale che l’Ambasciatore Han si accinge a svelare. L’ambasciatore infatti, è entrato in possesso di nuove ed esplosive prove relative all’organizzazione interna delle Triadi – la più potente e tristemente nota organizzazione criminale del mondo - e ha scoperto la vera identità di Shy Shen, il perno attorno al quale ruota l’intera organizzazione. -

List of Films Considered the Best

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Search List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page This list needs additional citations for verification. Please Contents help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Featured content Current events Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November Random article 2008) Donate to Wikipedia Wikimedia Shop While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications and organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned Interaction in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources Help About Wikipedia focus on American films or were polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the Community portal greatest within their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely considered Recent changes among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list or not. For example, Contact page many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best movie ever made, and it appears as #1 Tools on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawshank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst What links here Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. Related changes None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientific measure of the Upload file Special pages film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stacking or skewed demographics. -

Independent Cinema in the Chinese Film Industry

Independent cinema in the Chinese film industry Tingting Song A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2010 Abstract Chinese independent cinema has developed for more than twenty years. Two sorts of independent cinema exist in China. One is underground cinema, which is produced without official approvals and cannot be circulated in China, and the other are the films which are legally produced by small private film companies and circulated in the domestic film market. This sort of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has played a significant role in the development of Chinese cinema in terms of culture, economics and ideology. In contrast to the amount of comment on underground filmmaking in China, the significance of ‘within-system’ independent cinema has been underestimated by most scholars. This thesis is a study of how political management has determined the development of Chinese independent cinema and how Chinese independent cinema has developed during its various historical trajectories. This study takes media economics as the research approach, and its major methods utilise archive analysis and interviews. The thesis begins with a general review of the definition and business of American independent cinema. Then, after a literature review of Chinese independent cinema, it identifies significant gaps in previous studies and reviews issues of traditional definition and suggests a new definition. i After several case studies on the changes in the most famous Chinese directors’ careers, the thesis shows that state studios and private film companies are two essential domestic backers for filmmaking in China. -

Ai Weiwei, Jackie Chan and the Aesthetics, Politics, and Economics of Revisiting a National Wound

The Twelve Chinese Zodiacs: Ai Weiwei, Jackie Chan and the Aesthetics, Politics, and Economics of Revisiting a National Wound Frederik H. Green SAN FRANCISCO STATE UNIVERSITY hinese artist-activist Ai Weiwei 艾未未 and Hong Kong actor and director Jackie Chan C成龍 seem an unlikely pair to be included in an essay, yet, despite the different me- dia through which they express themselves, their respective celebrity status has, in the West, turned them into two of the best-known contemporary Chinese artists. In fact, to many West- erners, Ai Weiwei is to Chinese art what Jackie Chan is to Chinese martial arts cinema.1 In 2011 Ai Weiwei, who has had more solo exhibitions in Europe and America than any other Chinese artist, was named by the editors of ArtReview “the most powerful artist in the world,”2 while Jackie Chan has been described as a “star in the Hollywood pantheon . the only Chinese figure in popular culture who’s not regarded as some sort of imported novelty” (Wolf). What brings the two together here, however, is that in 2011 and 2012 they made headlines in the U.S. with a new installation and a new movie, respectively, both of which explore the same set of objects: twelve famous bronze heads depicting the animals of the Chinese zodiac. Originally the design of Jesuit scientists residing at the Chinese court during the Qing dynasty (1644- 1911), these bronze heads functioned as spouts for a complex water clock fountain that was part of an ensemble of European-style palaces inside the Old Summer Palace (Yuanming yuan 圓明園, literally ‘Garden of Perfect Brightness’). -

Innovation, Economic Development, and Intellectual Property in India and China Comparing Six Economic Sectors ARCIALA Series on Intellectual Assets and Law in Asia

ARCIALA Series on Intellectual Assets and Law in Asia Kung-Chung Liu Uday S. Racherla Editors Innovation, Economic Development, and Intellectual Property in India and China Comparing Six Economic Sectors ARCIALA Series on Intellectual Assets and Law in Asia Series Editor Kung-Chung Liu, School of Law, Singapore Management University, Singapore, Singapore This series, sponsored by the Applied Research Centre for Intellectual Assets and the Law in Asia (ARCIALA) focuses on intellectual assets and law in Asia, and also addresses international intellectual property (IP) norms that would impact Asian development. IP study thus far, globally speaking, is focused on the Western hemisphere as it continuously generates and disseminates new paradigms and legal norms to the rest of the world. Asia has been an importer and follower of those IP standards. The limited study of the Asian IP landscape in English is more on a national level, and seldom on a pan-Asia level which is the approach taken by this series. Asia as a growth engine of the world is now transitioning to a higher economic development level and will have a much more significant effect on international IP law moving forward. Key themes covered in the series include: innovation, economic growth and IP; the interplay between IP law and competition law; the intersection between IP and trade talks; patent; copyright; trademark; and individual country studies. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15958 Kung-Chung Liu • Uday S. Racherla Editors Innovation, Economic Development, and Intellectual Property in India and China Comparing Six Economic Sectors Editors Kung-Chung Liu Uday S. -

China, Film Coproduction and Soft Power Competition

China, Film Coproduction and Soft Power Competition Weiying Peng Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2015 Key Words China Coproduction Film coproduction Soft power Soft power competition i ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of China’s film internationalism and coproduction strategy. International coproduction has become a new area of industry debate in regard to China’s film industry. However, there has been limited scholarly attention, in both English and Chinese scholarship, paid to the activities of film coproduction between China and offshore parties. Specifically, the research looks at three representative film coproduction cases: Hong Kong and China based on Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA); US and China without any state-level agreements; Australia and China based on official film coproduction treaty. The broad intent of this study is to analyse the extent to which Chinese coproduction strategy functions as a form of soft power competition. Film coproduction in China, through the transfer of human capital, technology and knowledge, has significant implications for promoting China’s film ‘going out’, thus improving China’s soft power and building a better international image. The aim is to investigate the evolution of coproduction in the film industry, the process of coproduction, the foreign film companies’ strategies of adjustment to China’s state policy, and the challenges that hinder the coproduction. The contribution of this study comes in two parts: first, understanding the current environment for film coproduction in China and how foreign partners, especially those from western countries, deal with the historical, cultural, institutional and linguistic differences for coproduction. -

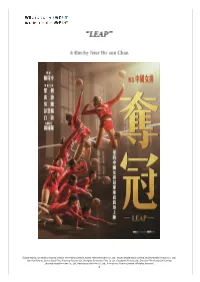

Gong Li (As Lang Ping)

© 2020 Beijing J.Q. Media Company Limited, We Pictures Limited, Huaxia Film Distribution Co., Ltd., Huanxi Media Group Limited, Beijing Alibaba Pictures Co., Ltd., Lian Ray Pictures, Such a Good Film, Shooting Pictures Ltd., Shanghai Dimension Films Co Ltd., Goodfellas Pictures Ltd., One Cool Film Production Limited, Zhejiang Hengdian Films Co., Ltd., Huoerguosi Jinyi Film Co., Ltd., X-Frequency Pictures Limited. All Rights Reserved. 1 Production Director : Peter Ho-sun Chan (Dearest, American Dreams in China) Producers : Jojo Hui Yuet Chun (Better Days, Soul Mate) Zhang Yibai (Us and Them) Scriptwriter : Zhang Ji (The Island, Dearest) Director of Photography : Zhao Xiaoshi (This Is Not What I Expected) Art Director : Sun Li (Dearest, American Dreams in China) Costume Designer : Dora Ng (Better Days, Us and Them) Editor : Zhang Yibo (Better Days) Starring : Gong Li (Saturday Fiction, Going Home) Huang Bo (The Island, Dearest) Wu Gang (A City Called Macau) Peng Yuchang (An Elephant Sitting Still, Our Shining Days) Bai Lang China Women’s Volleyball Team Production Company : We Pictures Limited Production Budget : US$18 million Languages: Mandarin, English Release date : 25 Sep 2020 (China) © 2020 Beijing J.Q. Media Company Limited, We Pictures Limited, Huaxia Film Distribution Co., Ltd., Huanxi Media Group Limited, Beijing Alibaba Pictures Co., Ltd., Lian Ray Pictures, Such a Good Film, Shooting Pictures Ltd., Shanghai Dimension Films Co Ltd., Goodfellas Pictures Ltd., One Cool Film Production Limited, Zhejiang Hengdian Films Co., Ltd., Huoerguosi Jinyi Film Co., Ltd., X-Frequency Pictures Limited. All Rights Reserved. 2 Synopsis With glorious days from 5 consecutive championships in the 1980s, the women's national volleyball team of China had transcended the conventional definition of sports in the hearts of Chinese people. -

The Politics of Images: Chinese Cinema in the Context Of

THE POLITICS OF IMAGES: CHINESE CINEMA IN THE CONTEXT OF GLOBALIZATION by HONGMEIYU A DISSERTATION Presented to the Comparative Literature Program and the Graduate School ofthe University of Oregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Doctor ofPhilosophy June 2008 11 University of Oregon Graduate School Confirmation of Approval and Acceptance of Dissertation prepared by: Hongmei Yu Title: "Politics ofImages: Chinese Cinema in the Context of Globalization" This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Doctor ofPhilosophy degree in the Department of Comparative Literature by: Tze-lan Sang, Chairperson, East Asian Languages & Literature David Leiwei Li, Member, English Janet Wasko, Member, Journalism and Communication Daisuke Miyao, Outside Member, East Asian Languages & Literature and Richard Linton, Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies/Dean ofthe Graduate School for the University of Oregon. June 14, 2008 Original approval signatures are on file with the Graduate School and the University of Oregon Libraries. iii © 2008 Hongmei Yu IV An Abstract ofthe Dissertation of Hongmei Yu for the degree of Doctor ofPhilosophy in the Comparative Literature Program to be taken June 2008 Title: THE POLITICS OF IMAGES: CHINESE CINEMA IN THE CONTEXT OF GLOBALIZATION Approved: _ Dr. Tze-Ian Sang This dissertation explores the interaction between filmmaking and the changing exigencies ofleftist political ideologies in China at different stages ofmodernity: semi colonial modernity, socialist modernity, and global modernity. Besides a historical examination ofthe left-wing cinema movement in the 1930s and socialist cinema in the Mao era, it focuses on the so-called "main melody" films that are either produced with financial backing by the state or sanctioned by governmental film awards in 1990s China. -

AMBASSADOR BIO Is All In

is all in AMBASSADOR BIO is all in LI BINGBING BIOGRAPHY Li Bingbing is one of China’s most famous and celebrated actresses. But it wasn’t until she graduated from high school, and a friend persuaded her to join the Shanghai Drama Institute in 1993, that she discovered a passion for acting that would change her life. Her debut role in Zhang Yuan’s Seventeen Years in 1999 earned her a Best Actress award at the Singapore Film Festival and kick-started her diverse and critically-acclaimed film and television career. In 2001, she joined the cast of the hit TV series Young Justice Bao in a role that made her a household name in China. In 2004, Li starred in the romantic comedy Waiting Alone, which received three Chinese Academy Awards. She went onto win Best Actress at the 2007 Huabiao Awards for the role, and at the 2008 Hundred Flower Awards for her performance in The Knot (China’s entry for Best Foreign Film at the 2008 Academy Awards). In 2008, she starred with Jet Li and Jackie Chan in The Forbidden Kingdom, which introduced her to global audiences. The next year, her powerful performance in The Message earned her a Best Leading Actress award at the Golden Horse Film Awards. Soon after, Li took her first lead role in an English language film in Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, which screened at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival. Next up, she will collaborate with Jackie Chan once more to produce and star in 1911, scheduled for release in September 2011 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Xinhai Revolution. -

Copyright by Yi Lu 2016

Copyright By Yi Lu 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Yi Lu certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Commercial Renaissance of Chinese Cinema: Movie Industry Reforms, Chinese Blockbusters, and Film Consumption in a Global Age Committee: ___________________________ Thomas Schatz, Supervisor ___________________________ Sung-sheng Chang, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Shanti Kumar ___________________________ Lalitha Gopalan ___________________________ Michael Curtin Commercial Renaissance of Chinese Cinema: Movie Industry Reforms, Chinese Blockbusters, and Film Consumption in a Global Age By Yi Lu, B.A; M.A; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree(s) of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2016 Dedication For my parents Acknowledgement This project would not have started without the inspiration of my supervisor Prof. Thomas Schatz. I wish to express my deepest gratitude to Prof. Schatz for his years of thoughtful, patient guidance, and support. He not only helped me grow intellectually through many hours of discussion, but also have set the standard of excellence as a scholar, mentor, instructor, and role model. Prof. Schatz has gracefully devoted time and energy to edit many drafts of the project, offer numerous insightful suggestions, and guide me through every stage of the writing process. I also wish to thank my co-supervisor, Prof. Sung-sheng Yvonne Chang, for her guidance, patience, and unfaltering support during the dissertation writing process and my graduate study. I have benefited greatly from her seminars and scholarships, and every formal and informal discussion with her. -

Il Ventaglio Segreto Pb Italiano

Presenta Un film prodotto da WENDI DENG MURDOCH e FLORENCE LOW SLOAN Diretto da WAYNE WANG Scritto da ANGELA WORMAN, MICHAEL RAY e dal premio Oscar RON BASS Musiche composte dal premio Oscar RACHEL PORTMAN Con GIANNA JUN, BING BING LI, VIVIAN WU e HUGH JACKMAN Tratto dal romanzo FIORE DI NEVE E IL VENTAGLIO SEGRETO scritto da Lisa See Edito in Italia da Longanesi Editore Durata 105’ I materiali sono scaricabili dall’ area stampa di www.eaglepictures.com DALL’ 8 LUGLIO AL CINEMA Ufficio Stampa Eagle Pictures Marianna Giorgi +39 335 1225525 [email protected] SINOSSI Ispirato al romanzo bestseller dal titolo FIORE DI NEVE E IL VENTAGLIO SEGRETO, della scrittrice Lisa See, il film racconta la storia di Fiore di neve e Lily, due bambine di sette anni, vissute ai tempi della Cina del 19° secolo, che subiscono la fasciatura dei piedi alla stessa età e nel medesimo giorno. Questo avvenimento unirà inesorabilmente i loro destini attraverso un legame conosciuto con il nome di laotong1 – un vincolo che le unisce assieme per l’eternità. Una volta sposate, nell’isolamento dei loro rispettivi matrimoni, le due ragazze troveranno il modo di comunicare furtivamente scrivendosi per mezzo di un linguaggio segreto chiamato nu shu, scritto tra le pieghe di un ventaglio bianco di seta. In una storia parallela, ambientata nella Shanghai dei nostri giorni, Nina e Sophia, due discendenti del laotong, cercano di mantenere salda la loro amicizia, nata sin dai tempi della loro infanzia, nonostante le loro carriere impegnative e le loro vite amorose complicate, in una Shanghai in perenne smania di evoluzione. -

I Am Not Madame Bovary" - a Name Came to Symbolize in the West the Archetype of the "Bad Woman and Wife"

2016 / China / 139 min / Format: DCP / Sound: 5.1 / Original version: Mandarin BEIJING SPARKLE ROLL MEDIA CORPORATION HUAYI BROTHERS MEDIA CORPORATION BEIJING SKYWHEEL ENTERTAINMENT CO., LTD. HUAYI BROTHERS PICTURES LTD. ZHEJIANG DONGYANG MAYLA MEDIA CO., LTD. Present Director FENG XIAOGANG Screenplay by LIU ZHENYUN Executive Producer WANG ZHONGLEI Executive Producer JERRY YE Producer HU XIAOFENG Director of Photography LUO PAN Production Designer HAN ZHONG Sound Supervisor WU JIANG Composer DU WEI Editor WILLIAM CHANG SUK PING Starring FAN BINGBING as Li Xuelian GUO TAO as Zhao Datou DA PENG as Wang Gongdao CONTEXT Li Xuelian is an ordinary Chinese woman living in a village. Because of her insistence in redressing an accusation against her, she has to negotiate with many people at various levels of society. She never imagined that, over the course of these confrontations, a single incident would snowball into another and later become something else entirely. After ten years, she has failed to set things right, only to learn a new lesson about the fickleness of human nature. Li sets out to redress an accusation made by her ex-husband who said: "Your name is Lian? Why do I think it's Pan Jinlian?" to which Li replied: "I'm no Pan Jinlian! 1" The film examines the conflicts that arise when a society evolves from one dependent on a system of grace and favors to one subject to a systemized rule of law. The female protagonist handles the conflicts with her ex-husband using every means in her power only to reveal the importance of the rule of law in a modern society.