Blanket Bogs and Raised Bogs What Is a Bog?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind Turbines, Sensitive Bird Populations and Peat Soils

Charity No. 229 325 Wind Turbines, Sensitive Bird Populations and Peat Soils: A Spatial Planning Guide for on-shore wind farm developments in Lancashire, Cheshire, Greater Manchester and Merseyside. July 2008 For more details, contact Tim Youngs [email protected] or Steve White [email protected] Produced by the RSPB and The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester & North Merseyside (LWT), in partnership with Lancashire County Council, Natural England and the Merseyside Environmental Advisory Service (EAS) 1 Contents Section Map Annex Page Background 2 How to use the alert maps 4 Introduction 4 Key findings 5 Maps showing ‘important populations’ of ‘sensitive bird 1-5 6- 10 species’ and deep peat sensitive areas in Lancashire, Cheshire, Greater Manchester and Merseyside Legal protection for birds and habitats 11 Methodology and definitions 12- 15 Caveats and notes 16 Distribution of Whooper Swan, Bewick’s Swan and Pink- 17- 22 footed Goose in inland areas of Lancashire, Cheshire, Greater Manchester and Merseyside Thresholds for ‘important’ populations’ (of sensitive species) 1 23 Definition of terms relating to ‘sensitive species’ of bird 2 24 Background The Inspectors who carried out the Examination in Public of the draft NW Regional Spatial Strategy (RSS) between December 06 to February 07, proposed that 'Maps of broad areas where the development of particular types of renewable energy may be considered appropriate should be produced as a matter of urgency and incorporated into an early review of RSS'. This proposal underpins the North West Regional Assembly’s (NWRA) research that is being carried out by Arup consultants. The Secretary of State's response is 'In line with PPS22, we consider that an evidence-based map of broad locations for installation of renewable energy technologies would benefit planning authorities and developers. -

Western Samoa

A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania In: Scott, D.A. (ed.) 1993. A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania. IWRB, Slimbridge, U.K. and AWB, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania WESTERN SAMOA INTRODUCTION by Cedric Schuster Department of Lands and Environment Area: 2,935 sq.km. Population: 170,000. Western Samoa is an independent state in the South Pacific situated between latitudes 13° and 14°30' South and longitudes 171° and 173° West, approximately 1,000 km northeast of Fiji. The state comprises two main inhabited islands, Savai'i (1,820 sq.km) and Upolu (1,105 sq.km), and seven islets, two of which are inhabited. Western Samoa is an oceanic volcanic archipelago that originated in the Pliocene. The islands were formed in a westerly direction with the oldest eruption, the Fagaloa volcanics, on the eastern side. The islands are still volcanically active, with the last two eruptions being in 1760 and 1905-11 respectively. Much of the country is mountainous, with Mount Silisili (1,858 m) on Savai'i being the highest point. Western Samoa has a wet tropical climate with temperatures ranging between 17°C and 34°C and an average temperature of 26.5°C. The temperature difference between the rainy season (November to March) and the dry season (May to October) is only 2°C. Rainfall is heavy, with a minimum of 2,000 mm in all places. The islands are strongly influenced by the trade winds, with the Southeast Trades blowing 82% of the time from April to October and 54% of the time from May to November. -

Questioning Ten Common Assumptions About Peatlands

Questioning ten common assumptions about peatlands University of Leeds Peat Club: K.L. Bacon1, A.J. Baird1, A. Blundell1, M-A. Bourgault1,2, P.J. Chapman1, G. Dargie1, G.P. Dooling1,3, C. Gee1, J. Holden1, T. Kelly1, K.A. McKendrick-Smith1, P.J. Morris1, A. Noble1, S.M. Palmer1, A. Quillet1,3, G.T. Swindles1, E.J. Watson1 and D.M. Young1 1water@leeds, School of Geography, University of Leeds, UK 2current address: Centre GEOTOP, CP 8888, Succ. Centre-Ville, Montréal, Québec, Canada 3current address: Geography, College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, UK _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY Peatlands have been widely studied in terms of their ecohydrology, carbon dynamics, ecosystem services and palaeoenvironmental archives. However, several assumptions are frequently made about peatlands in the academic literature, practitioner reports and the popular media which are either ambiguous or in some cases incorrect. Here we discuss the following ten common assumptions about peatlands: 1. the northern peatland carbon store will shrink under a warming climate; 2. peatlands are fragile ecosystems; 3. wet peatlands have greater rates of net carbon accumulation; 4. different rules apply to tropical peatlands; 5. peat is a single soil type; 6. peatlands behave like sponges; 7. Sphagnum is the main ‘ecosystem engineer’ in peatlands; 8. a single core provides a representative palaeo-archive from a peatland; 9. water-table reconstructions from peatlands provide direct records of past climate change; and 10. restoration of peatlands results in the re-establishment of their carbon sink function. In each case we consider the evidence supporting the assumption and, where appropriate, identify its shortcomings or ways in which it may be misleading. -

PLTA-0103 Nature Conservancy 3/19/04 4:00 PM Page 1

PLTA-0103 Nature Conservancy 3/19/04 4:00 PM Page 1 ............................................................. Pennsylvania’s Land Trusts The Nature Conservancy About Land Trusts Conservation Options Conserving our Commonwealth Pennsylvania Chapter Land trusts are charitable organizations that conserve land Land trusts and landowners as well as government can by purchasing or accepting donations of land and conservation access a variety of voluntary tools for conserving special ................................................................ easements. Land trust work is based on voluntary agreements places. The basic tools are described below. The privilege of possessing Produced by the the earth entails the Pennsylvania Land Trust Association with landowners and creating projects with win-win A land trust can acquire land. The land trust then responsibility of passing it on, working in partnership with outcomes for communities. takes care of the property as a wildlife preserve, the better for our use, Pennsylvania’s land trusts Nearly a hundred land trusts work to protect important public recreation area or other conservation purpose. not only to immediate posterity, but to the unknown future, with financial support from the lands across Pennsylvania. Governed by unpaid A landowner and land trust may create an the nature of which is not William Penn Foundation, Have You Been to the Bog? boards of directors, they range from all-volunteer agreement known as a conservation easement. given us to know. an anonymous donor and the groups working in a single municipality The easement limits certain uses on all or a ~ Aldo Leopold Pennsylvania Department of Conservation n spring days, the Tannersville Cranberry Bog This kind of wonder saved the bog for today and for to large multi-county organizations with portion of a property for conservation and Natural Resources belongs to fourth-graders. -

Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate Change: Main Report

Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate change Main Report Published By Global Environment Centre, Kuala Lumpur & Wetlands International, Wageningen First Published in Electronic Format in December 2007 This version first published in May 2008 Copyright © 2008 Global Environment Centre & Wetlands International Reproduction of material from the publication for educational and non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior permission from Global Environment Centre or Wetlands International, provided acknowledgement is provided. Reference Parish, F., Sirin, A., Charman, D., Joosten, H., Minayeva , T., Silvius, M. and Stringer, L. (Eds.) 2008. Assessment on Peatlands, Biodiversity and Climate Change: Main Report . Global Environment Centre, Kuala Lumpur and Wetlands International, Wageningen. Reviewer of Executive Summary Dicky Clymo Available from Global Environment Centre 2nd Floor Wisma Hing, 78 Jalan SS2/72, 47300 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Tel: +603 7957 2007, Fax: +603 7957 7003. Web: www.gecnet.info ; www.peat-portal.net Email: [email protected] Wetlands International PO Box 471 AL, Wageningen 6700 The Netherlands Tel: +31 317 478861 Fax: +31 317 478850 Web: www.wetlands.org ; www.peatlands.ru ISBN 978-983-43751-0-2 Supported By United Nations Environment Programme/Global Environment Facility (UNEP/GEF) with assistance from the Asia Pacific Network for Global Change Research (APN) Design by Regina Cheah and Andrey Sirin Printed on Cyclus 100% Recycled Paper. Printing on recycled paper helps save our natural -

Blanket Bogs

SCOTTISH INVERTEBRATE HABITAT MANAGEMENT Blanket bogs Claish Moss © Scottish Natural Heritage Introduction that may also provide important sub-habitats. Britain has about 10-15% of the total global area Invertebrates in upland moorland or bog habitats of blanket bog, making it one of the most are an essential component of the diet of many important international locations for this habitat. bird species; cranefly larvae and adults have 80-85% of Britain’s blanket bog habitat is found in been shown to be important food for grouse Scotland, covering 1.8 million hectares, and chicks and breeding waders, such as Golden representing 23% of the country’s land area. This plover. Adult grouse may also eat craneflies to makes Scotland an internationally important supplement their diet of heather shoots. country for blanket bog. Managing habitats to benefit these invertebrates Blanket bog is found in cool, wet, typically is thus likely to have a significant impact on the oceanic climates, where it can cover whole survival of upland birds. landscapes, such as in the North-West of In addition, the Scottish Invertebrate Species Scotland. Peat accumulates slowly over many Knowledge Dossiers: Pseudoscorpiones years and can reach depths exceeding 5m, indicated the possibility that the Bog chelifer although 0.5-3m is more typical. Blanket bog is (Microbisium brevifemoratum ) is likely to occur in “ombrotrophic”, that is, the water and mineral Scottish bogs—highlighting that there may yet be supply comes entirely from atmospheric sources unrecorded species in this important Scottish (rainwater, mist, cloud-cover). The water habitat (Legg, 2010). chemistry is nutrient-poor and acidic and the Support for management described in this habitat is dominated by acid-loving plant document is available through Scotland Rural communities, especially Sphagnum mosses. -

Lowland Raised Bog (UK BAP Priority Habitat Description)

UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Habitat Descriptions Lowland Raised Bog From: UK Biodiversity Action Plan; Priority Habitat Descriptions. BRIG (ed. Ant Maddock) 2008. This document is available from: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5706 For more information about the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) visit http://www.jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5155 Please note: this document was uploaded in November 2016, and replaces an earlier version, in order to correct a broken web-link. No other changes have been made. The earlier version can be viewed and downloaded from The National Archives: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20150302161254/http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page- 5706 Lowland Raised Bog The definition of this habitat remains unchanged from the pre-existing Habitat Action Plan (https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110303150026/http://www.ukbap.org.uk/UKPl ans.aspx?ID=20, a summary of which appears below. Lowland raised bogs are peatland ecosystems which develop primarily, but not exclusively, in lowland areas such as the head of estuaries, along river flood-plains and in topographic depressions. In such locations drainage may be impeded by a high groundwater table, or by low permeability substrata such as estuarine, glacial or lacustrine clays. The resultant waterlogging provides anaerobic conditions which slow down the decomposition of plant material which in turn leads to an accumulation of peat. Continued accrual of peat elevates the bog surface above regional groundwater levels to form a gently-curving dome from which the term ‘raised’ bog is derived. The thickness of the peat mantle varies considerably but can exceed 12m. -

Peat from Penguins to Palm Trees

Organic Soils in the UK Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. Peat from Penguins to Palm Trees Janet Moxley [email protected] (CEH), Chris Evans (CEH), Nicole Archer (BGS), Mary-Ann Smyth (Crichton Carbon Centre) Introduction The UK has 14 Overseas Territories (OTs) and 3 Crown Dependencies (CDs). The Falkland Islands contain large areas of organic soils, with smaller areas in the Isle of Man and the Caribbean OTs. Where sufficient data are available GHG emissions from the OTs and CDs which have ratified or are likely to ratify the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol are included in the UK GHG inventory. We review current understanding of organic soils in these areas. The Falkland Islands Estimates of peat area vary between 282 kha (BGS and CEH, unpublished data) and 548 kha (Wilson et al, 1993). The BGS/CEH estimate assumes that all valley-bottom deposits, and 33% of upland organo-mineral soils on shallow slopes, are peat, based on new field survey data. Falkland peatlands comprise a mixture of upland blanket bog covered with Astelia pumila, White grass (Cortadelia pilosa), Diddle Dee (Empetrum rubrum), and white grass-dominated valley mire. Rainfall is low, resulting in only low presence of Sphagnum magellanicum, and (combined with high wind speeds) in high susceptibility to erosion. The main pressures are from grazing by large numbers of sheep, use of prescribed fire for vegetation management, dredging of stream channels to increase drainage, wildfires, effects of historic bomb craters, domestic peat extraction, and the use of turf banks as windbreaks. Peat distribution has been mapped, but peat condition has not been documented. -

Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries

E3: ECOSYSTEMS, ENERGY FLOW, & EDUCATION Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries Eco-systems, Energy Flow, and Education: Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries CONTENT OUTLINE Big Idea / Objectives / Driving Questions 3 Selby Gardens’ Field Study Opportunities 3 - 4 Background Information: 5 - 7 What is an Estuary? 5 Why are Estuaries Important? 5 Why Protect Estuaries? 6 What are Mangrove Wetlands? 6 Why are Mangrove Wetlands Important? 7 Endangered Mangroves 7 Grade Level Units: 8 - 19 8 - 11 (K-3) “Welcome to the Wetlands” 12 - 15 (4-8) “A Magnificent Mangrove Maze” 16 - 19 (7-12) “Monitoring the Mangroves” Educator Resources & Appendix 20 - 22 2 Eco-systems, Energy Flow, and Education: Where Land Meets Sea: Mangroves & Estuaries GRADE LEVEL: K-12 SUBJECT: Science (includes interdisciplinary Common Core connections & extension activities) BIG IDEA/OBJECTIVE: To help students broaden their understanding of the Coastal Wetlands of Southwest Florida (specifically focusing on estuaries and mangroves) and our individual and societal interconnectedness within it. Through completion of these units, students will explore and compare the unique contributions and environmental vulnerability of these precious ecosystems. UNIT TITLES/DRIVING QUESTIONS: (Please note: many of the activities span a range of age levels beyond that specifically listed and can be easily modified to meet the needs of diverse learners. For example, the bibomimicry water filtration activity can be used with learners of all ages. Information on modification for -

Guide for Constructed Wetlands

A Maintenance Guide for Constructed of the Southern WetlandsCoastal Plain Cover The constructed wetland featured on the cover was designed and photographed by Verdant Enterprises. Photographs Photographs in this books were taken by Christa Frangiamore Hayes, unless otherwise noted. Illustrations Illustrations for this publication were taken from the works of early naturalists and illustrators exploring the fauna and flora of the Southeast. Legacy of Abundance We have in our keeping a legacy of abundant, beautiful, and healthy natural communities. Human habitat often closely borders important natural wetland communities, and the way that we use these spaces—whether it’s a back yard or a public park—can reflect, celebrate, and protect nearby natural landscapes. Plant your garden to support this biologically rich region, and let native plant communities and ecologies inspire your landscape. A Maintenance Guide for Constructed of the Southern WetlandsCoastal Plain Thomas Angell Christa F. Hayes Katherine Perry 2015 Acknowledgments Our thanks to the following for their support of this wetland management guide: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (grant award #NA14NOS4190117), Georgia Department of Natural Resources (Coastal Resources and Wildlife Divisions), Coastal WildScapes, City of Midway, and Verdant Enterprises. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge The Nature Conservancy & The Orianne Society for their partnership. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of DNR, OCRM or NOAA. We would also like to thank the following professionals for their thoughtful input and review of this manual: Terrell Chipp Scott Coleman Sonny Emmert Tom Havens Jessica Higgins John Jensen Christi Lambert Eamonn Leonard Jan McKinnon Tara Merrill Jim Renner Dirk Stevenson Theresa Thom Lucy Thomas Jacob Thompson Mayor Clemontine F. -

Blanket Bog Toolkit

BLANKET Outcomes and BOG improvements LAND MANAGEMENT GUIDANCE CONTENTS Introduction 3 Introduction 3 How to use this pack 4 Blanket bog toolkit This guidance for land managers and conservation advisers has been collaboratively 7 State 2: Bare Peat produced by representatives of the Uplands Management Group (UMG) in response to a 11 State 3: Dwarf shrub dominated blanket bog request from the Uplands Stakeholder Forum (USF) for best practice guidance. 15 State 4: Grass and/or sedge dominated blanket bog 19 State 5: Modified blanket bog It is designed to put into practice the joint voluntary Defra Blanket Bog Restoration Strategy agreed by the Uplands Stakeholder Forum (USF). 23 State 6: Active hummock/hollow/ridge blanket bog This guidance will enable land managers to take steps to improve the vegetation characteristics and hydrological properties of blanket bog, which is defined by a peat depth of over 0.4m, across the uplands of England (see Q1–2). The five agreed outcomes (see Q5) sought by land managers and conservationists via this approach are: = the capture and storage of carbon = improved water quality and flow regulation = high levels of biodiversity = a healthy red grouse population = good quality grazing The UMG provides practitioner input to the USF, chaired by Defra. The Group seeks to produce guidance for practitioners covering a range of upland management activity. For more information go to: www.uplandsmanagement.co.uk HOW TO USE THIS PACK The guidance consists of: = DECISION MAKING TOOLKIT Use it out on the hill to agree the starting condition of the blanket bog and to decide on the best management methods to improve it. -

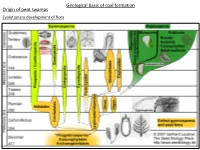

Geological Basis of Coal Formation Origin of Peat Swamps Evolutionary Development of Flora

Geological basis of coal formation Origin of peat swamps Evolutionary development of flora Peat swamp forests are tropical moist forests where waterlogged soil prevents dead leaves and wood from fully decomposing. Over time, this creates a thick layer of acidic peat. Large areas of these forests are being logged at high rates. True coal-seam formation took place only after Middle and Upper Devonian, when the plants spread over continent very rapidly. Devonian coal seams don’t have any economic value. The Devonian period was a time of great tectonic activity, as Euramerica and Gondwana drew closer together. The continent Euramerica (or Laurassia) was created in the early Devonian by the collision of Laurentia and Baltica, which rotated into the natural dry zone along the Tropic of Capricorn, which is formed as much in Paleozoic times as nowadays by the convergence of two great air-masses, the Hadley cell and the Ferrel cell. In these near- deserts, the Old Red Sandstone sedimentary beds formed, made red by the oxidized iron (hematite) characteristic of drought conditions. Sea levels were high worldwide, and much of the land lay under shallow seas, where tropical reef organisms lived. The deep, enormous Panthalassa (the "universal Devonian Paleogeography ocean") covered the rest of the planet. Other minor oceans were Paleo-Tethys, Proto- Tethys, Rheic Ocean, and Ural Ocean (which was closed during the collision with Siberia and Baltica). Carboniferous flora Upper Carboniferous is known as bituminous coal period. 30 m 7 m Permian coal deposits formed predominantly from Gymnosperm Cordaites. Cretaceous and Tertiary peats were formed from angiosperm floras.