Church History L8--Hus Wycliffe Erasmus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erasmus on the Study of Scriptures

-- CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL MONTHLY Erasmus the Exegete MARVIN ANDERSON Erasmm on the Study of Scriptures CARL S. MEYER Erasmus, Luther, and Aquinas PHILIP WATSON Forms of Church and Ministry ERWIN L. LUEKER Homiletics Book Review Vol. XL December 1969 No. 11 Erasmus on the Study of Scriptures CARL S. MEYER Erasmus (1469-1536)1 was the editor one of the important theologians of the of the first published Greek New Tes first half of the 16th century 6 as well as tament printed from movable type (1516).2 an earnest advocate of the study of Scrip He translated the books of the New Testa tures.7 ment into Latin 3 and also paraphrased I them (except Revelation) in that lan Prerequisites for Biblical studies coin guage.4 He published the notes of Lorenzo cide with the characteristics one brings to Valla (1406--1457) on the New Testa the philosophy of Christ, Erasmus held. ment.5 He must likewise be accounted as This meant a heart undefiled by the sordid ness of vice and unaffected by the dis 1 The standard edition of Erasmus' writings is DesMerii Erasmi Roterodami Opera Omnia, quietude of greed.8 We must therefore ed. J. Clericus (10 vols.; Leyden, 1703-1706). examine the philosophia Christi concept The reprint issued by Gregg Press in London, in Erasmus as the basis for understanding 1961-1962, was used. Cited as LB. Ausgewiihtte Werke, ed. Hajo Holborn his approach to Sacred Writ. (Munich: C. H. Vedagsbuchhandlung, 1933). Erasmus used a variety of phrases for Cited as AW. Ausgewiihlte Schriften, ed. Werner Welzig this concept. -

Importance of the Reformation

Do you have a Bible in the English language in your home? Did you know that it was once illegal to own a Bible in the common language? Please take a few minutes to read this very, very brief history of Christianity. Most modern-day Christians do not know our history—but we should! The New Testament church was founded by Jesus Christ, but it has faced opposition throughout its history. In the 50 years following the death and resurrection of Jesus, most of His 12 apostles were killed for preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ. The Roman government hated Christians because they wouldn’t bow down to their false gods or to Caesar and continued to persecute and kill Christians, such as Polycarp who they martyred in 155 AD. Widespread persecution and killing of Christians continued until 313 AD, when the emperor Constantine declared Christianity to be legal. His proclamation caused most of the persecution to stop, but it also had a side effect—the church and state began to rule the people together, effectively giving birth to the Roman Catholic Church. Over time, the Roman Catholic Church gained more and more power—but unfortunately, they became corrupted by that power. They gradually began to add things to the teachings found in the Bible. For example, they began to sell indulgences to supposedly help people spend less time in purgatory. However, the idea of purgatory is not found in the Bible, and the idea that money can improve one’s favor with God shows a complete lack of understanding of the truth preached by Jesus Christ. -

Forerunners to the Reformation

{ Lecture 19 } FORERUNNERS TO THE REFORMATION * * * * * Long before Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the Wittenberg Door, there were those who recognized the corruption within the Roman Catholic Church and the need for major reform. Generally speaking, these men attempted to stay within the Catholic system rather than attempting to leave the church (as the Protestant Reformers later would do). The Waldensians (1184–1500s) • Waldo (or Peter Waldo) lived from around 1140 to 1218. He was a merchant from Lyon. But after being influenced by the story of the fourth-century Alexius (a Christian who sold all of his belongings in devotion to Christ), Waldo sold his belongings and began a life of radical service to Christ. • By 1170, Waldo had surrounded himself with a group of followers known as the Poor Men of Lyon, though they would later become known as Waldensians. • The movement was denied official sanction by the Roman Catholic Church (and condemned at the Third Lateran Council in 1179). Waldo was excommunicated by Pope Lucius III in 1184, and the movement was again condemned at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. • Waldensians were, therefore, persecuted by the Roman Catholics as heretics. However, the movement survived (even down to the present) though the Waldensians were often forced into hiding in the Alps. • The Waldensian movement was characterized by (1) voluntary poverty (though Waldo taught that salvation was not restricted to those who gave up their wealth), (2) lay preaching, and (2) the authority of the Bible (translated in the language of the people) over any other authority. -

![162 [Part I. Review of Erasmus's Preface]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3126/162-part-i-review-of-erasmuss-preface-133126.webp)

162 [Part I. Review of Erasmus's Preface]

162 WORD AND FAITH For although you think and write wrongly about free choice,k yet I owe you no small thanks, for you have made me far more sure of my own position by letting me see the case for free choice put forward with all the energy of so distinguished and powerful a mind, but with no other effect than to make things worse than 27. Luther had stated this as early as before. That is plain evidence that free choice is a pure fiction;27 in his 1518 Heidelberg Disputation (WA for, like the woman in the Gospel [Mark 5:25f.], the more it is 1:353–74; LW 31:[37–38] 39–70). Here treated by the doctors, the worse it gets. I shall therefore abun- he explains the free will to be just a dantly pay my debt of thanks to you, if through me you become word, not a real thing (res de solo titulo). better informed, as I through you have been more strongly con- firmed. But both of these things are gifts of the Spirit, not our own achievement. Therefore, we must pray that God may open my mouth and your heart, and the hearts of all human beings, and that God may be present in our midst as the master who informs both our speaking and hearing. But from you, my dear Erasmus, let me obtain this request, that just as I bear with your ignorance in these matters, so you in turn will bear with my lack of eloquence. God does not give all his gifts to one man, and “we cannot all do all things”; or, as Paul says: “There are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit” [1 Cor. -

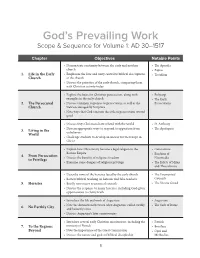

Scope & Sequence

God’s Prevailing Work Scope & Sequence for Volume 1: AD 30–1517 Chapter Objectives Notable Points • Demonstrate continuity between the early and modern • The Apostles church • Papias 1. Life in the Early • Emphasize the love and unity central to biblical descriptions • Tertullian Church of the church • Discuss the priorities of the early church, comparing them with Christian activity today • Explore the basis for Christian persecution, along with • Polycarp examples in the early church • The Early 2. The Persecuted • Discuss common responses to persecution, as well as the Persecutions Church view encouraged by Scripture • Note ways that God can turn the evils of persecution toward good • Discuss ways Christians have related with the world • St. Anthony • Discern appropriate ways to respond to opposition from • The Apologists 3. Living in the unbelievers World • Challenge students to develop an answer for their hope in Christ • Explain how Christianity became a legal religion in the • Constantine Roman Empire • Eusebius of 4. From Persecution • Discuss the benefits of religious freedom Nicomedia to Privilege • Examine some dangers of religious privilege • The Edicts of Milan and Thessalonica • Describe some of the heresies faced by the early church • The Ecumenical • Review biblical teaching on heresies and false teachers Councils 5. Heresies • Briefly note major ecumenical councils • The Nicene Creed • Discuss the response to major heresies, including God-given opportunities to clarify truth • Introduce the life and work of Augustine • Augustine • Note the distinctions between what Augustine called earthly • The Sack of Rome 6. No Earthly City and heavenly cities • Discuss Augustine’s later controversies • Introduce several early Christian missionaries, including the • Patrick 7. -

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions

What Happened in the First Century -- Creation of New Testament Writings; Spread of Christianity; Rise of Persecutions • The words and sayings of Jesus are collected and preserved. New Testament writings are completed. • A new generation of leaders succeeds the apostles. Nevertheless, expectation still runs high that the Lord may return at any time. The end must be close. • The Gospel taken through a great portion of the known world of the Roman empire and even to regions beyond. • New churches at first usually begin in Jewish synagogues around the empire and Christianity is seen at first as a part of Judaism. • The Church faces a major crisis in understanding itself as a universal faith and how it is to relate to its Jewish roots. • Christianity begins to emerge from its Jewish womb. A key transition takes place at the time of Jewish Revolt against Roman authority. In 70 AD Christians do not take part in the revolt and relocate to Pella in Jordan. • The Jews at Jamnia in 90 AD confirm the canon of the Hebrew Scriptures. The same books are recognized as authoritative by Christians. • Persecutions test the church. Jewish historian Josephus seems to express surprise that they are still in existence in his Antiquities in latter part of first century. • Key persecutions include Nero at Rome who blames Christians for a devastating fire that ravages the city in 64 AD He uses Christians as human torches to illumine his gardens. • Emperor Domitian demands to be worshiped as "Lord and God." During his reign the book of Revelation is written and believers cannot miss the reference when it proclaims Christ as the one worthy of our worship. -

THE SCHOLASTIC PERIOD Beatus Rhenanus, a Close Friend Of

CHAPTER THREE MEDIEVAL HISTORY: THE SCHOLASTIC PERIOD Beatus Rhenanus, a close friend of Erasmus and the most famous humanist historian of Germany, dated the rise of scholasticism (and hence the decay of theology) at “around the year of grace 1140”, when men like Peter Lombard (1095/1100–1160), Peter Abelard (1079–1142), and Gratian († c. 1150) were active.1 Erasmus, who cared relatively little about chronology, never gave such a precise indication, but one may assume that he did not disagree with Beatus, whose views may have directly influenced him. As we have seen, he believed that the fervour of the gospel had grown cold among most Christians during the previous four hundred years.2 Although his statement pertained to public morality rather than to theology,3 other passages from his work confirm that in Erasmus’ eyes those four centuries represented the age of scholasticism. In his biography of Jerome, he complained that for the scholastics nobody “who had lived before the last four hundred years” was a theologian,4 and in a work against Noël Bédier he pointed to a tradition of “four hun- dred years during which scholastic theology, gravely burdened by the decrees of the philosophers and the contrivances of the sophists, has wielded its reign”.5 In one other case he assigned to scholasti- cism a tradition of three centuries.6 Thus by the second half of the twelfth century, Western Christendom, in Erasmus’ conception, had entered the most distressing phase of its history, even though the 1 See John F. D’Amico, “Beatus Rhenanus, Tertullian and the Reformation: A Humanist’s Critique of Scholasticism”, Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte 71 (1980), 37–63 esp. -

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe Is Born in Yorkshire

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe is born in Yorkshire, England 1369?: Jan Hus, born in Husinec, Bohemia, early reformer and founder of Moravian Church 1384: John Wycliffe died in his parish, he and his followers made the first full English translation of the Bible 6 July 1415: Jan Hus arrested, imprisoned, tried and burned at the stake while attending the Council of Constance, followed one year later by his disciple Jerome. Both sang hymns as they died 11 November 1418: Martin V elected pope and Great Western Schism is ended 1444: Johannes Reuchlin is born, becomes the father of the study of Hebrew and Greek in Germany 21 September 1452: Girolamo Savonarola is born in Ferrara, Italy, is a Dominican friar at age 22 29 May 1453 Constantine is captured by Ottoman Turks, the end of the Byzantine Empire 1454?: Gütenberg Bible printed in Mainz, Germany by Johann Gütenberg 1463: Elector Fredrick III (the Wise) of Saxony is born (died in 1525) 1465 : Johannes Tetzel is born in Pirna, Saxony 1472: Lucas Cranach the Elder born in Kronach, later becomes court painter to Frederick the Wise 1480: Andreas Bodenstein (Karlstadt) is born, later to become a teacher at the University of Wittenberg where he became associated with Luther. Strong in his zeal, weak in judgment, he represented all the worst of the outer fringes of the Reformation 10 November 1483: Martin Luther born in Eisleben 11 November 1483: Luther baptized at St. Peter and St. Paul Church, Eisleben (St. Martin’s Day) 1 January 1484: Ulrich Zwingli the first great Swiss -

Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages

jussi hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Studia Fennica Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Jussi Hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Finnish Literature Society · Helsinki Studia Fennica Historica 2 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2002 Jussi Hanska and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB Conversion: eLibris Media Oy ISBN 978-951-746-357-7 (Print) ISBN 978-952-222-818-5 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-819-2 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 0355-8924 (Studia Fennica Historica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sfh.2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. -

Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection Jason Skirry University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Skirry, Jason, "Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 179. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/179 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/179 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection Abstract This dissertation presents a unified interpretation of Malebranche’s philosophical system that is based on his Augustinian theory of the mind’s perfection, which consists in maximizing the mind’s ability to successfully access, comprehend, and follow God’s Order through practices that purify and cognitively enhance the mind’s attention. I argue that the mind’s perfection figures centrally in Malebranche’s philosophy and is the main hub that connects and reconciles the three fundamental principles of his system, namely, his occasionalism, divine illumination, and freedom. To demonstrate this, I first present, in chapter one, Malebranche’s philosophy within the historical and intellectual context of his membership in the French Oratory, arguing that the Oratory’s particular brand of Augustinianism, initiated by Cardinal Bérulle and propagated by Oratorians such as Andre Martin, is at the core of his philosophy and informs his theory of perfection. Next, in chapter two, I explicate Augustine’s own theory of perfection in order to provide an outline, and a basis of comparison, for Malebranche’s own theory of perfection. -

29 CHILOSI 249 254.Ps, Page 3 @ Preflight

MINISTERO PER I BENI E LE ATTIVIT À CULTURALI © BOLLETTINO D’ARTE E AF D CAB : E DE CAD AE AE DE BA D EA S (2009 -S II) A A A A C E DE CAD AE AE DAD A AA A A A EA. AE, EA E AC DA A EC CA EEC A CASA EDITRICE LEO S. OLSCHKI 29_CHILOSI.qxp:Layout 1 1-12-2010 16:21 Pagina 249 MARIA GRAZIA CHILOSI IL MONUMENTO DEL CARDINALE GUILLAUME DURAND A SANTA MARIA SOPRA MINERVA. LO SPOSTAMENTO, I RESTAURI E ALCUNI DATI SULLA TECNICA ESECUTIVA* Il monumento funebre del vescovo di Mende, Guil- concavo è decorato a mosaico; la camera del giacente, laume Durand, morto nel 1296, opera di Giovanni di incassata nella muratura, è costituita da tre pareti che Cosma, era in origine nella Cappella di Ognissanti, figurano un drappo appeso, sorretto alle estremità da poi Altieri; ne fu rimosso nel 1670 per consentire i due angeli; in essa è deposto il corpo del defunto. lavori di ammodernamento, voluti da Clemente X Sotto il giacente il catafalco è riccamente drappeggia- nella cappella di famiglia, e fu ricollocato sull’adiacen- to e mostra in basso cinque scudi mosaicati con l’im- te parete di testata del braccio destro del transetto presa della famiglia Durand. Al di sotto è murata una (figg. 1 e 2). È stato oggetto di una campagna di lapide con iscrizione incisa. restauro nel 1998 da parte della Soprintendenza per i Il monumento risulta oggi gravemente sacrificato Beni Artistici e Storici di Roma.1) nel piccolo spazio tra la Cappella Altieri e la Cappella Il monumento, formato da blocchi apparentemente di San Tommaso d’Aquino, schiacciato tra elementi -

1 Early History

1 Early History 1. EAREEARLYLYY HISHHISTORYTORORY 5 1 Early History The fijirst attempts to study Arabic in Europe occurred in the Iberian peninsula. There, after the Arab conquests in the eighth century, a flourishing culture developed which was primarily Islamic but in which Christians and Jews played an important part. With the reconquest of Toledo from the Muslims by Alfonso VI of Castile a translation movement came into being which is known as the ‘Medieval Renaissance,’ and which was based in the cathedral of Toledo. The translations, often testifying to an imperfect knowledge of Arabic, covered a selection of scholarly works in the domains of medicine, geography, astronomy, mathematics, physics and philosophy.1 A substantial part consisted of texts by Greek and Hellenistic authors such as Aristotle, Euclid, Galen and Ptolemy which were no longer available in the West in their original form but which had been translated into Arabic from the ninth century onward under the Abbasid dynasty. In addition to these there were the works of Arabic-speaking scholars such as Ibn Sina (‘Avicenna’, c.980–1037), al-Ghazali (‘Algazel’ 1058–1111) and Ibn Rushd (‘Averroes’, 1126–1198), translated directly from Arabic into Latin. In most cases the translators relied on the assistance of local Arabic speakers. One example is the surgical manual of Abu ʼl-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-‘Abbas al-Zahrawi from Granada (c.936–c.1013), whose name was transformed into Latin as Albucasis, Abulcasis, Alsaharavius or other variants. The Latin translation of the text was made by the best known translator in Toledo, the Italian Gerardo da Cremona (1114–1187).